(Earth Eats theme plays)

KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington Indiana, I'm Kayte Young and this is Earth Eats.

TANEISHA HENLINE: There's no more watching your food being cooked, there's no more hanging out with the Jamaican. It's (laughs) it's just "Hi, what's going on? Everything good? See you next time."

KAYTE YOUNG: This week on our show we visit with Taneisha Henline, chef and owner of Top Shotta Jerk Chicken in Bloomington, about running a food truck during a pandemic and how cooking traditional food connects her with her ancestors. We have stories from Harvest Public Media's series on how food insecurity in the U.S. has been heightened by COVID-19 and Josephine McRobbie brings us the final installment in her series with Joe O'Connell on the Oregon fishing industry. That's all coming up in the next hour here on Earth Eats, so stay with us.

(Transition music)

RENEE REED: Earth Eats is produced from the campus of Indiana University in Bloomington Indiana. We wish to acknowledge and honor the Miami, Delaware, Potawatomi, and Shawnee people on whose ancestral homelands and resources Indiana University was built.

KAYTE YOUNG: Welcome to Earth Eats, I'm your host Kayte Young. Renee Reed has the Earth Eats news, hello Renee.

RENEE REED: Hello Kayte. We've got stories from Chad Bouchard and Harvest Public Media. Shoppers looking for their favorite cup of tea should soon see plenty of it. Beef and pork production are nearly back to pre-pandemic levels after disruptions during the spring when outbreaks of COVID-19 sent workers home and meat plants reduced production. That left farmers, ranchers and feed lots with animals onsite longer than expected, and reduced the supply of fresh beef and pork. Oklahoma State University livestock economist Lee Schulz says very little beef cattle remains backed up.

LEE SCHULZ: It's taken the rest of the summer and rear end of the fall to sort of catchup if you will. I think we are largely caught up at this point, the indications are that we have largely addressed the backlog.

RENEE REED: Most backlog pigs also made it to market, despite fears that hundreds of thousands of hogs would be euthanized and never reach the food supply, the actual numbers were much lower than most estimates.

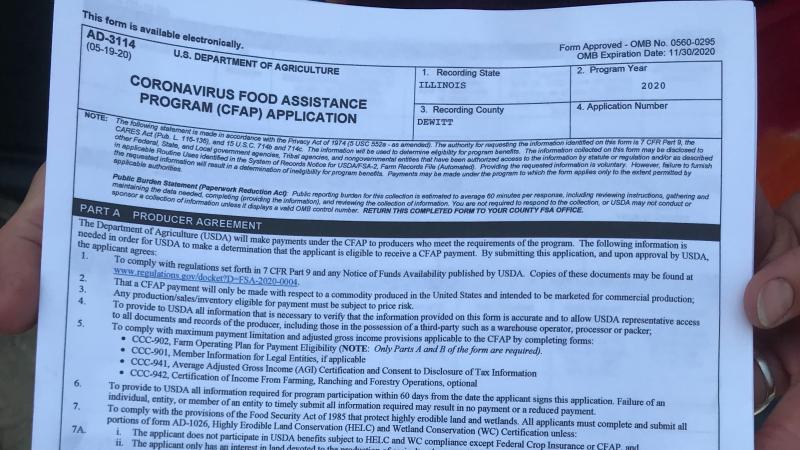

Farmers will receive more coronavirus relief dollars from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, but as Harvest Public Media's Dana Cronin reports, not all of the initial relief package has been dolled out yet.

DANA CRONIN: President Trump announced the additional relief at a campaign rally in Wisconsin, a key battleground state. The second round of payments will total about $14 billion dollars and comes on the heels of the first round of AG relief through the coronavirus food assistance program, which still has $6 billion unpaid dollars in the pot. Jonathan Coppess is an AG analyst with the University of Illinois.

JONATHAN COPPESS: So yeah just under half of it is probably just repurposing the funds that were not spent in the previous program. I think this is a fair estimate given what little we know about it at this point in time.

DANA CRONIN: In a statement a USDA spokesperson said they are still processing applications from round one, and they don't know how much will be left when they're done. I'm Dana Cronin, Harvest Public Media.

RENEE REED: As wildfires continue to rage across millions of acres in western states and smoke hangs over devastated communities, farmworkers continue to work the harvest season. Workers face risks of exposure to heat, smoke, and stubbornly high rates of new coronavirus cases. Health researchers warn that smoke causes or worsens a list of medical ailments from respiratory and cardiovascular disease to diabetes.

Smoke from this years western wildfires has caused souring pollution levels that far exceed those considered safe by Environmental Protection Agency standards. An EPA Air Quality Index or AQI usually measures from 0 to about 500, with up to 100 considered to be generally safe. Under California regulations employers must provide workers with respirators like N95 masks if the level is over 150. Areas of Oregon near Portland on September 17th registered 380, considered to be a level hazardous enough that everyone should avoid going outside. The AQI topped 300 on some of the worst days across the west coast in recent weeks. In central California near Fresno, levels have registered a whopping 780.

Farm labor activists warn that the combination of wildfire smoke and coronavirus will amplify infection rates and death tolls among workers, half of whom are undocumented or migrants who lack legal protection and live in crowded housing conditions. Many farmworkers have preexisting health conditions due to low socioeconomic status, lacking healthcare and access to services.

One farmworker who had migrated from Oaxaca Mexico and did not want to use his name due to his immigration status, told PRI's The World that smoke had affected his health while picking almonds in Fresno without protection. He complained of having difficulty sleeping due to sore throat, coughing and eye irritation. After learning that there was an anonymous Spanish-English tip line for labor law violations in California, the man said that he would not call the number for fear of it getting traced back to him.

Environmental health experts are calling for more enforcement of California's safety laws, requiring employers to offer N95 masks in poor air quality and limiting time outdoors in extreme heat. California's Occupational Safety and Health Administration told the world that the agency only has 200 field enforcement officer to inspect 200,000 workplaces across the state that could be affected by smoke. In a California poll this summer, United Farm Workers found that 84% of the workers asked had not received N95 masks by their employers.

Thanks to Chad Bouchard and Harvest Public Media's Amy Mayer and Dana Cronin for those reports. For Earth Eats News, I'm Renee Reed.

(Earth Eats News Theme plays)

KAYTE YOUNG: Thank you Renee.

One final note about our news team, Taylor Killough has been bringing us news reports for many years, first here at WFIU and then from Louisville Kentucky. Sadly she had to say goodbye to Earth Eats recently as she enters a graduate program in journalism. We hope to hear from her again on the show in the future, perhaps in a new capacity. And in the meantime, thank you Taylor. We will miss you and we wish you all the best.

(Revised Earth Eats news theme music)

KAYTE YOUNG: After COVID-19 arrived in small towns, rural leaders were faced with a new challenge - getting food to hungry families safely. In one small Nebraska town, Harvest Public Media's Christina Stella reports they've had to find new ways to feed families in need.

CHRISTINA STELLA: Lexington Nebraska, population 11,000, isn't exactly used to traffic, but over the past few months a line of cars has been forming like clockwork every Thursday morning since June. They're headed to a white tent outside Saint Anne's Parish in the hopes of picking up a USDA Farmers to Families food box.

MICHAELA KOPF: It's awesome. They get one box of produce, a box of dairy, sometimes we get milk, and then one box of proteins. And it's different every week.

CHRISTINA STELLA: That's Michaela Kopf of the Lexington Community Foundation, she stands in the scorching August heat directing cars to the tent where masked volunteers pack boxes. Most weeks she says hundreds of boxes of food are gone in an hour.

MICHAELA KOPF: Sometimes it's lined up all the way to highway 30. So there's definitely a need and it has increased since COVID for sure.

CHRISTINA STELLA: Like many rural areas, food insecurity is a chronic problem in Lexington where 16% of residents live below the poverty line. The town has a food pantry, Martha Draskovic managed it as a one woman operation for 10 years. On a break from moving boxes she recalls how COVID-19 gave her a surge in demand.

MARTHA DRASKOVIC: It became clear when my shelves started going empty. So we kind of had to do a new game plan.

CHRISTINA STELLA: Many families rely on their kids getting two meals a day at school. Losing that, coupled with the sudden increase in unemployment was the perfect storm. People who didn't typically use the pantry, or even nutrition programs like SNAP were suddenly in need.

MARTHA DRASKOVIC: They were over income at one point so they weren't eligible for the benefit but once they were home for two to three weeks they were still out of income but yet no food.

CHRISTINA STELLA: Empty shelves weren’t her only hurdle. At the time supply chains nation wide were faltering. Finding bulk pantry staples like pasta and peanut butter was a struggle.

MARTHA DRASKOVIC: I kind of had my director going to different stores, doing online shopping, picking up for me in Grand Island.

CHRISTINA STELLA: Tammy Jeffs at the Community Action Partnership of mid-Nebraska says it was hard to stay afloat without hurting the rest of the town. In the rural area, the grocery might restock just once a week.

TAMMY JEFFS: We were aware that... you know, we don't we want to buy 40 packs of something and all the grocery store is getting is 50 packs, you've now just sent everybody to your pantry cause you bought everything. So... (laughs).

CHRISTINA STELLA: Plus, once they found the food they had to figure out how to get it to people who couldn't come to the pantry. Some of those people were seniors, others were workers at the local Tyson meatpacking plant who were quarantined without a way to feed themselves. So Draskovic started delivering.

TAMMY JEFFS: At first it was just myself. They were just doing that and then I kinda you know recruited other people to start coming in and just helping.

CHRISTINA STELLA: When it got around town that the pantry was struggling residents made sure it was stocked.

TAMMY JEFFS: We started getting different you know financial donations, items, businesses started reaching out and you know now we kind of have a backstock. So we're kind of prepared to see if we get that second runabout.

CHRISTINA STELLA: Orthman Manufacturing - an agricultural equipment company is one of the local companies that helps distribute food. Scott McKelvey is the local plant manager. He says strong community ties have made all the difference in Lexington. He called a friend at the Rotary club to bring Hot Meals USA to town, serving 18,000 meals since April.

SCOTT MCKELVEY: It doesn't matter, somebody drives up in 2017 Cadillac decked out to the 9's, nobody cares because you don't know what's going on with that family.

CHRISTINA STELLA: McKelvey says these kind of mutual aid networks give him hope. Lately he's needed it.

SCOTT MCKELVEY: With everything else that's going on in the United States right now, this is a feel good moment. And it's not just in the midwest, there's these moments that are going on all over the country to help feed families in need.

CHRISTINA STELLA: He makes his way back under the tent. Most of the boxes are gone. McKelvey and the other volunteers start loading up their cars and figuring out where to deliver the extra food. It doesn't take them long to make a plan. Cristina Stella Harvest Public Media.

KAYTE YOUNG: That story is part two in a series from Harvest Public Media taking a deeper look at how food insecurity in the U.S. has been exacerbated by the pandemic. Stay tuned for part three in the series on how a group in Oklahoma is helping farmers get excess food to those who need it most through gleaning. That's coming up later in the show, stay with us.

(Energetic music)

Maybe it was a friend on Facebook, bragging on their tasty takeout meal on a Friday night, perhaps it was the aroma spicy meats on a grill, the smoke from a barbeque wafting through the air as you rode your bike on 4th street downtown one night around dinner time. You caught a flash of a bright red and green food truck at the corner of your eye, but kept peddling home. Maybe you've heard of Top Shotta Jerk Chicken, maybe you've even tried their food. Either way, now you have the chance to hear from the owner of this unique food truck on the streets of Bloomington Indiana.

TANEISHA HENLINE: My name is Tanisha Henline. I am the owner of Top Shotta Jerk Chicken, an authentic Jamaican food truck here in Bloomington Indiana.

KAYTE YOUNG: I met up with Tanisha in a city park on 3rd street one morning to talk about her food and the story behind the business.

TANEISHA HENLINE: On the food truck I make traditional Jamaican rice and peas, which in Jamaica we call peas and beans, cause the beans peas. But here it's peas and green, that's what people think rice and peas is, but it's actually kidney beans with white rice. And traditionally we make that on Sundays, it's really fun so I make that everyday.

I also make jerk chicken tacos. In Jamaica I've never had a taco but when I came here I realized that everyone loved tacos from a food truck, so I do that. And then I do the traditionally jerk chicken. In Jamaica it's chopped up but I leave it on the bone. Traditionally it's spicy, but I make my jerk sauce from scratch, the marinade from scratch, and it's on this side. It's not spicy at all just a hint of flavor.

Every eat you eat it, you love the food, it's very delicious. I also do my own coleslaw that I call the shotta slaw. I also have slices of potato bread. And sometimes I do specials of ox tail, curry boat, brown stew chicken, curry chicken and I post that on my facebook page anytime I have those.

KAYTE YOUNG: I asked Tanisha why she loved the meat on the bone, even though it's not traditional.

TANEISHA HENLINE: You know actually it's cause that's what Americans prefer, and I'm trying to reach out to Americans - that's the target audience, and I'm trying to reach out. So I leave it on the bone but if you want it chopped I will gladly chop it for you. If you want that experience of it being chopped up and me putting on your sauce and it being spicy from the get-go, I am more than happy to do that.

So it would be on the grill whole, I'll season it in spaced pieces then after it's done, I'll chop it up with a cleaver, put it in a file paper, put on ketchups, the sauce is on there, and then hand it to you.

So I get the chicken fresh and I marinade it with the sauces and the spices that I make from scratch that's traditional to my homeland. And I marinade it and then cook it on the grill. It's very healthy as well. The thing about jerk is that we have a dry rub that's made of our traditional spices. And usually you do that at home, if it's just the family, you don't want to do it too fancy, you use your dry rub. Then you have a wet rub, and if that's for commercial use - that you're trying to do something of it more fancy, you use your wet rub on there.

But at Top Shotta I support the dry rub and the wet rub and you have to put coals in the chicken, you have to get the seasoning on the meat, the meat, and that is also a process of the jerk chicken. That's how my ancestors actually did it.

It's all fresh ingredients. I have onions, garlic, cause you have to use peppers and stuff like that cause that's healthy too. And then I have dry rubs which is I use over 30 mixes of dry rubs into one to make that into my jerk. And then I have another set of the wet rub which is the onions and scallions, the tomatoes, and then I have allspice. A Jamaican is no Jamaican food without allspice. And the you add that to your rub with a whole lot of other stuff.

KAYTE YOUNG: Vegetarians don't worry. Top Shotta has something for you.

TANEISHA HENLINE: Sometimes I have customers who don't eat meat. The rice and peas is for vegetarians, there's no broth in there, I make the water taste delicious and put the rice in there with the peas and everything. There's nothing that a vegetarian would be, you know like, "Oh no I don't want that."

Then the tacos, I don't have to put the chicken in there. Cause the tacos come with shredded cabbage, a slice of pear, and in Jamaica, an avocado we call that a pear, but we know that a pear, here is an American pear.

So it's a slice of avocado, some chicken usually but then I do have to put the chicken in, some cabbage, I add tomatoes, onions, scallions and sweet peppers, and also the sauce. And the sauce has nothing that's not friendly to vegetarian in it.

And I also have a burrito that I could just not put any meat in, that has coleslaw, has tomatoes, onion, cheese, sour cream, the rice and peas, and that's all in a wrap.

KAYTE YOUNG: Tamisha shared her understanding of the origins of the jerk tradition in Jamaica.

TANEISHA HENLINE: In the 1650's, they were named Maroons, those are my ancestors, they're called the Maroons. They were the first escaped slaves on Jamaica. They were on the plantations when the Spaniards captured them and then the British took over in 1655.

And on that plantation they were like, "Hold on, we don't want to do this anymore. We're not gonna be slaves, enough is enough, and we're gonna fight for our freedom."

So they escaped, they went into the mountains - the other word for a Maroon is a mountaineer. They went up in the mountains and they were being followed, so they had to come up with a way - how are we gonna eat, without being captured?

So they decided we can make the herbs of the earth, all the seasoning the dry rubs, we're gonna mix that into our spice, we're gonna kill the boar, the pig - that's the first thing that was jerked in Jamaica. We're gonna kill the boar we're gonna dig a hole in the ground, and they would put pimento wood - that's also a native of Jamaica, and allspice into the ground, season the meat, cover it with more pimento wood, then put dry leaves on top, and that would smother the smoke. So that's also smoking it, jerking it underneath, and the British soldiers can't tell that there's actually a fire going on. So that's where it actually came from. At first...

KAYTE YOUNG: And what about the word 'jerk'?

TANEISHA HENLINE: I can remember in history class that Gitanos - and those were the first settlers for Christopher Columbus, they were the first ones there, the Tainos and the Arawaks. You know what they used to do, they would have the same spice but they would dry the meat. So it's kinda like the jerky. But then when the Maroons got ahold of the recipe they were like, "We don't like this part. We want a bit more juicier, a bit more flavorful, a bit more hearty. That if we eat piece of meat, we actually can hold us within these wartimes." So they added a bit more flavor and other seasonings that created the wet rub and the dry rub for the jerk.

It's grilled and it's smoked at the same time. And it's not just, it's not like barbeque, it's a whole process and every time I do it, it's such pride.

My husband, he like. I actually met him, the way that I got to come here in Jamaica, I had to be like, I have to say this because I wouldn't be here, with this food truck, had I not met him.

So I was in Jamaica six years ago, I lived there. And I met him on vacation. And he flirted with me the entire time but I just like, "I'm not too sure."

KAYTE YOUNG: They stayed connected after he returned to Bloomington. Eli invited her to visit, they fell in love, married, and Taneisha moved to Bloomington.

TANEISHA HENLINE: But while I love being here, the food was not the same and it was a big culture shock for me, and I was very depressed. So in order to stay here and still be happy I had to find a way to cook. And if I'm cooking all the time, and I'm enjoying this good food, I feel like I should share it. I would be selfish for keeping onto this good food all for myself.

KAYTE YOUNG: While Taneisha did not cook professionally in Jamaica she certainly had experience in the kitchen.

TANEISHA HENLINE: I grew up extremely poor. I didn't have plumbing, I used candles for studying for my schoolwork, so I didn't have the luxury of going out to eat. You had to buy the chicken back, the chicken neck, the worst part of the chicken. I had to make that into something that's delicious that you can eat. So even in Jamaica I always had to cook, because if I don't cook, I don't eat.

And so I've always had a strong connection to food, but coming here it got even stronger because I couldn't get the things that I really wanted. But now that I have the food truck and I'm cooking what I love, and things that I couldn't even afford in Jamaica, like ox tail - I dreamt of eating ox tail. I remember my friend, I asked her for some of her gravy, just to see what it tasted like. And now being able to buy that and cook that and share it to others, it makes me so happy. And I just have to thank the community for just accepting me for who I am and for what I'm doing.

(Transition Music)

TANEISHA HENLINE: I've been in business now would be my third full year. I actually started two and a half years ago when it was in the winter and it was so cold! I could manage the cool I still can. But I was like, oh well even though it's cold out there when I start, as soon as I was up and running and I got certified by the city I just wanted to get out there to start sharing my culture. So this year would actually be in winter my third full year.

Well as a food truck, any restaurant you have to have a commissary, and that's one where commissary will shout out to One World Commissary. We have a commissary there, I keep my dry foods there. On the truck I try to do as much as I can before the day of. I have an hour that I start my prepping because we prep everyday fresh, no frozen food. So that's how I do it.

We are closed on Sundays, Mondays and Tuesdays, and then Wednesdays I do lunch on the westside at Dirtsportz. And then Thursdays, Fridays and Saturday I am on 3rd and College across from Atlas. And I have permission to be there at 5:00. So I get there at 5:00, I do my prepping and then I can serve by 6:00. And then that's weather permitting because of the charcoal grill, I have a pull behind the food truck. So if it's raining I can't really be out there in the rain, because the grill wants... it gets wet and the charcoal, it's not possible. So I post every morning if I'll be out that day.

KAYTE YOUNG: Taneisha posts her location and any specials of the day on Top Shotta's Facebook page and on Instagram. Regulars know to check there first. I'm Kayte Young, this is Earth Eats and we're speaking with Taneisha Henline of Top Shotta Jerk Chicken in Bloomington Indiana. After a short break we'll hear how Taneisha adapted to the COVID-19 restrictions and what it means to her to share food in the community. Stay with us.

(Trendy music)

RENEE REED: Make sure you never miss an episode. Subscribe to our podcast. It's the same great stories in your podcast feed. Just search for Earth Eats wherever you listen to podcasts. While you're there, please leave us a review. It means a lot to us and it helps other people find us.

(Transition Music)

KAYTE YOUNG: Welcome back, you're listening to Earth Eats. I'm Kayte Young. We're talking with Taneisha Hemline. She's the owner and chef at Top Shotta Jerk Chicken and Cuisine. It's a food truck in Bloomington Indiana. With everything that the restaurant industry has been through since widespread shut down orders started in March of this year, I asked Taneisha what adjustments she has had to make to comply with the COVID-19 restrictions.

TANEISHA HENLINE: In the past I loved the fact that my customers could come to the truck, talk me with me while their chicken is being grilled right there, they could see their chicken. I would sometimes ask them which pieces they would like, you choose your piece of meat. You see it come off, fresh off the grill. And I'm there fixing your food, we talk a little more, then you leave. Some people like to eat there, and tell me how good the food is, which I love.

But now with the COVID and the pandemic, I have to encourage preordering. So once I pause I get calls for orders, and then I get there, I start doing my prep, then I start cooking. And they would just have to pickup their food and leave. There's no more watching your food being cooked, there's no hanging out with a Jamaican. (laughs) It's just "How, how goin? Everythign good. See you next time."

Which is still nice, but I miss people being able to watch their chicken on the grill. Things have changed drastically. No... I mean before I used to give out hand sanitizer, wipes, I used to do that before cause I like doing that, that's a good thing for a restaurant to do. But then now I have to ensure that. Cause my husband helps me out on the truck, he drives it for me and he helps move the charcoal grill, so we have to give hand sanitizer to everyone once they touch their money. We gotta make sure we're wiping all the surfaces, which I used to do before but now it's even more strenuous, things that you have to do to ensure that you are in accordance with the law, which is what you have to do right now.

KAYTE YOUNG: Taneisha prefers that customers call first to preorder. I asked if walkup ordering is possible, say if you were walking by, caught a whiff of the sizzling seasoned meats from the grill.

TANEISHA HENLINE: Yes, sometimes I can't really tell if I'll have a busy day or not. Sometimes it's busy, sometimes it's not. Somedays you can walkup and right away I can serve you. Other days I do have the chicken but I can't serve you yet because I have so many preorders. So you can always walkup to the truck and order but I can't guarantee that I'll be able to serve you immediately.

KAYTE YOUNG: I wondered if jerk chicken is something that you would normally find served as street food in Jamaica.

TANEISHA HENLINE: This is a popular, one of the most popular street foods in Jamaica. Anywhere on the street there's a jerk man, and usually they're there in the evenings, not in the mornings. They're usually there for lunch, for dinner and then late night for when the parties are going on, 2-3 o'clock in the morning. You're leaving a party, he's right out there with his soup and his jerk. You're so hungry, it smells so good, you just have to get some food. It's a whole tradition for us.

The jerk chicken man when you go to the club or you're on the street, he's just there with his little pan smelling up whole place with this aroma of food. You go there, you buy food, you talk to him. It's a whole social business and that's what Negril - where I'm from in Jamaica, is actually known for. Or beaches, the jerk chicken man just there on the street, but I wanted to bring that but I couldn't bring it here cause of the laws. So I had to get the entire food truck. I couldn't just have the pan how it is back home.

KAYTE YOUNG: Here on Earth Eats we interviewed entrepreneurs in the food world and I am always curious to hear what it is that drives them to start their own business. I personally find the idea terrifying.

TANEISHA HENLINE: It's nerve wracking. You know back home in Jamaica because things was rough, I always had to work and pay bills and I was like, "Well I would love to be something more one day, but I don't see it materializing yet. So I'm just going to work towards whatever may come."

KAYTE YOUNG: After moving to Bloomington, Taneisha worked a couple of desk jobs but she wasn't happy. She was missing her culture, she was missing her food. She started to find the ingredients to make her favorite dishes at home and she began to wonder if she could start cooking for others.

TANEISHA HENLINE: So I was like well, if I can get the food that I like from home and I can cook it, and I've not been happy with working relationships that I've put myself in here then I can do this. And I spoke to my husband about it and he's like, "Well I've been eating your food for a while and yes it's good and I wouldn't just say that cause you're my wife. It's really good. So I will back you 100%."

And just having his support, knowing that he believes that I can do it, just made me want to do it even more.

When I tried to get the food here, even when I went out of state, I knew I could do better. And I'm not trying to knock anyone's business, big (shout)out to all Jamaicans who are trying to make something big out there, but I've tried it and I was like, "I can do better." You know? "And Bloomington needs this." Bloomington has a lot of different type of people, a lot ethnicity here, but I says like, "There's no Jamaican. There's different stuff that I've tried but it's not Jamaican."

And I was like, "You know what? I can do it. And I feel like the community would embrace that too." And they have, which I am grateful for.

KAYTE YOUNG: I asked if it was just her and Eli running the business or did she have other employees?

TANEISHA HENLINE: Yes, it's just the two of us. I feel like I can't control my product once somebody else is in charge, and I like being able (to say) it's from me, this is from my heart, and it's to you, straight from me. And I feel like if I get anybody else they won't care as much as I do. Cause this is my culture, this is the way I was grown, this is how I was raised.

KAYTE YOUNG: So how has business been?

TANEISHA HENLINE: You know, to be honest I would say that I... slow and steady win the race. People are slowly hearing about me and the good thing about me is once you've had the food once... I have had so many people once, I'm seein' them the next day, and the next day. And a return face is always good, but now that more people hearing about me, it's slowly more now picking up. Yeah because back then nobody knew that I was even out. Nobody knew so I'm slow, I feel like this is the first year that more of the Bloomington community even know that there's a Jamaican food truck in town.

KAYTE YOUNG: I asked Taneisha to reflect on what sharing food means to her.

TANEISHA HENLINE: For me food, first you eat with your eyes, so for me when I'm plating my food, I feel a sense of pride, because my ancestors - the Maroons, what they did, they had to hide and do it. And because of them I am free today to share it across the world. As a Jamaican being in Indiana, to me it's a huge deal.

We as Jamaicans we're small but we are everywhere, sharing our culture, making people happy. When I have a customer who I think is 8 years old, and he saves his allowance that he gets on a weekly basis to come to the food truck and buy his family food. And he waves his $20 and I run out there and I hug him and (I say) "I'm so happy that you loved the food."

And he says "The food is amazing"

I've had kids, babies, told me that the food is so good, it makes so happy. It makes me extremely happy. Because I do it with a sense of pride and if I wouldn't eat it, then I'm not serving it. And I cook it to the best of my ability that if my ancestors are anywhere watching me, they're gonna say, "Well done my child, you're doing the right thing."

And I have to have a sense of pride anytime when I do this. Every time I go on that truck, she's, her name is Nanny of the Maroons. The name of the truck is actually one of our heroines, the Nanny of the Maroon. She lead the Morant Bay rebellion, she lead a lot of the wars that happened between the British. But eventually they had to sign a treaty with us, because we were not gonna remain slaves anymore. And every time I cook a piece of chicken, I remember that if it weren't for them being brave enough to stand up for years and shedding their blood, I can't do this. I wouldn't be able to be here.

And I'm just happy that the community accepts me, and they have been so loving towards me, everybody has been so nice. And I couldn't wish it any better, to be in a community that's so diverse and everybody's so loving. I haven't had a bad experience being in Bloomington. I've had great encounters with people, everybody loves me. You know it's a Jamaican food truck, the food is great.

KAYTE YOUNG: I couldn't let Taneisha go without asking her about the name of her business; Top Shotta.

TANEISHA HENLINE: So if you're top shotta you're a hustler, you're a go getter, nobody messes with you, you're all about the Benjamins. You're just trying to hustle and get your slice of the cake. You're a top shotta. Yup. And I'm the best at what I do, and I'm a top shotta at jerking chicken (laughs). You're a boss. You're a boss at what you do, and people know. They respect you for that.

KAYTE YOUNG: And a boss she is. That was Taneisha Hemline, owner and chef of Top Shotta Jerk Chicken and Cuisine, a food truck found on the streets of Bloomington Indiana. Check the Earth Eats website for details on Top Shotta's menu and location, EarthEats.org.

(Transition music)

KAYTE YOUNG: COVID-19 has made it more difficult for farmers to sell produce. From farmers' markets to restaurants, leaving food in the field. Harvest Public Media's Seth Bodine reports on how one group in Oklahoma is helping farmers get excess food off the farm and to those who need it most.

SETH BODINE: While coronavirus has hampered farmers here, usually it's the weather that threatens crops. Last year Joe Tierney's farm was in trouble. Heavy rain was causing flooding all along the Arkansas river. Before he knew it water from the nearby creek was creeping forward.

JOE TIERNEY: There's really anything you can do except just watch it.

SETH BODINE: Tierney had evacuate the farm leaving behind his field full of vegetables. That's when he called for help. Katie Plohocky is visiting the farm again, she remembers looking at the fields in jeopardy.

KATIE PLOHOCKY: Just romaine lettuce the size of my torso that was growing and in just all of these rows and to know that it was going to be under water in two days and all of that was gonna be ruined.

SETH BODINE: Plohocky founded the Health Community Store Initiative in an effort to bring fresh food to food desserts in Tulsa. The mission was simple; rescue as many cabbages as possible and bring them to those in need before the leafy goods were underwater.

KATIE PLOHOCKAYTE: You know I actually went and leased a UHaul truck just so I could you know get it all because time was of the essence.

SETH BODINE: Plohocky brought back four truckloads of cabbage and lettuce to the groups mobile grocery store. That cabbage rescue plan is part of Hands to Harvest, it aims to reduce food waste by getting volunteers to pick the excess food off the field and not just during disasters. It's a practice called greening; the tradition goes back to biblical times. There are similar programs all over the country. Plohocky says that farmers often recognize that there's extra food in the fields but getting it off the farm can be difficult.

KATIE PLOHOCKY: The farmers don't have the manpower or the time to load it up and deliver it somewhere. And so there's a missing link in between the farm and the pantries or the food banks or the schools or whoever needs that food. And so that's what we were trying to do was just fill in that gap a little bit.

SETH BODINE: Shawn Peterson founded the association of cleaning organizations. He says the COVID-19 pandemic isn't a crisis for them, but now there's a lot more food to pickup.

SHAWN PETERSON: There's so much more produce because the disruptions in the system whether it was the restaurants that were closed that the small scale farmer can't sell to now, or you know, schools that were closed that the large scale farmer can't sell to.

SETH BODINE: Excess food on the farm is actually pretty common even during normal times. Research from Sana Clara University estimates that about a third of crops grown on U.S. farms go unharvested. Greg Baker is a professor at Santa Clara University. He says farmers often will only let gleaners into the field after the very last harvest.

GREG BAKER: They can't afford to have someone who is not well trained come into their field and do something wrong, like not wash their hands after using the toilet, and then possibly contaminate an entire field.

SETH BODINE: Gleaning isn't the only strategy Plohocky is using to combat food waste while keeping people fed. When the Tulsa Farmers' market closed she says she was buying produce directly from the farmers. That food went to a program's COVID-19 grocery relief program.

KATIE PLOHOCKY: It's just making that connection between... whose growing the food and whose needing the food because there should be no one in the United States that should be food insecure.

SETH BODINE: While gleaning won't solve food insecurity, Plohocky says it's one way to get fresh food to people who need it. Seth Bodine, Harvest Public Media.

(Piano music)

KAYTE YOUNG: That was part three from Harvest Public Media taking a deeper look at how food insecurity in the U.S. has been heightened by the pandemic. Listen for the final installments in this series in coming weeks here on Earth Eats. I'm Kayte Young.

Workers in Oregon's commercial fishing industry share a close knit culture. Now they're trying to imagine how regional tourism fits into that community. This story from Josephine McRobbie and public folklorist Joe O'Connell was produced based on original field research for the Oregon Folklife Network.

SARA SKAMSER: The men were after me something awful after I won the armwrestling championship.

(Guitar chords)

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Swapping stories about work and play is an Oregon fishing industry tradition.

SARA SKAMSER: By then the bar is packed, it was after a halibut opener. There's 300 people in there.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Sara Skamser is a netmaker in Newport.

SARA SKAMSER: I went and signed up, weighed in at the unlimited weight divisions, sat back down. My name got called and there was Shirley, the arm wrestling champion of four years. And she just grabs ahold of me, and is turning colors and grunting, and I’m holding steady. And then I realized I had not tried yet. And I slammed her right down.

(Cheering and clapping)

ANNOUNCER: Thank you very much.

SECOND ANNOUNCER: Whoa did you hear that?

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Some poets and musicians near the coast have elevated commercial fishing lore to an artform. The string band Brownsmead Flats are performing at winery in the town of Nehalem.

BROWNSMEAD FLATS: (Singing) It isn't very far to Astoria's Bar, but a very long journey it can be. It can start at the mountains...

NED HEAVENRICH: I sort of like refer to us as crabgrass. Sort of blue grassy sound, but with maritime flavor.

BROWNSMEAD FLATS: (Singing)...when they rode all night to fish in the morning and lives in...

NED HEAVENRICH: My name is Ned Heavenrich and I live in Brownsmead.

DAN SUTHERLAND: My name is Dan Sutherland and I also live in Brownsmead.

NED HEAVENRICH: Brownsmead Oregon. There's Ray Raihala who plays banjo and then John Fenton our base player. Larry Moore mandolin player.

Larry Moore do you want to join in on this?

LARRY MOORE: I could join in.

NED HEAVENRICH: Yeah, yeah.

BROWNSMEAD FLATS: It is worth more than gold when we fill our...

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: When they sing about Astoria's Bar they were not talking about a pub but rather the intimidating waters where the Columbia River meets the Pacific ocean.

MARY GARVEY: (Chatting indistinctly in the background)

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: The song was written by somebody just across the river.

MARY GARVEY: Mary Garvey. I live in Long Beach Washington now, I've lived here about 18 years. I don't think of myself as a performer. I guess I've written enough songs I could say I'm a songwriter.

Destination, I could do the destination. That's Alaska, I was singing at FisherPoets and it turns out that...

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: For both Mary Garvy and Brownsmead flats, singing about the region is essential.

MARY GARVEY: I think it's very important to... if you can, write about specific people, specific events, communities.

GARY SUTHERLAND: We like to do a lot of songs about living on the coast or near the coast.

MARY GARVEY: And my stuff sort of does that by accident. I don't set out to do it.

NED HEAVENRICH: You know it's just what this area is, you know. You write about where you live.

MARY GARVEY: So I think the song... like I said, there's something you could sort of tap into.

NED HEAVENRICH: You know maybe if you live in Wisconsin you'd write about cows and milk, I don't know, and cheese. And here you write about fish and water and trees, and the rain.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Both artists are mainstays at the FisherPoets Gathering, an annual event held by and for insiders. Pretty much everyone onstage at the gathering is or has been a commercial fisher.

LARRY MOORE: In Astoria the FisherPoets Gathering would ask for some tune to be maybe orientated to be more maritime, or did you have something to do with the fishing industry. And of course Ray and Ned have been a fisherman.

RAY SUTHERLAND: Yeah

GARY SUTHERLAND: Ray probably was kind of the first person to get into that. His father was a gillnet fisherman on the Columbia river for many many years and he grew up in that tradition. And so he fished with his dad and then he was a fish buyer. You know he had a lot of stories to tell about...

MARY GARVEY: Kate Gabel did a really good job singing this on a CD.

(Sings) Hold on, and hold on, and frightfully concerned.

Hold on, hold on, there's news that we have learned.

Hold on, hold on, there's a boat that's overturned.

The coastguard is...

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Mary Garvey never made her living on the water but her songs help commemorate events in the community.

MARY GARVEY: "Hold on" - it's a true story, it was right after Christmas and somebody started to go down. He had in his pocket a new cellphone that someone had given him. He in the water, all of the sudden remembers his phone. He gets the phone out and he gets ahold of... I guess the coast guard or I guess somebody, but they didn't know where he was.

And he gave a few descriptors and I guess the community somehow said, "Well he must be near here."

They went circling around looking for him and on this very last wave, he was underwater totally. His very last wave I've heard. He waved to them, and they saw him. It was getting I think it was getting dark.

This one happens so close to FisherPoets. Sometimes if there's a time urgency I might cause I knew it should be sung at FisherPoets cause they actually, some of them... I don't know if they knew the people but they knew the boat, and they knew the place.

(Finishes singing) Amazing rescue, amazing.

(Sound of Brownsmead Flats tuning up)

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Some of the songs by Brownsmead Flats address transitions taking place on the coast.

BROWNSMEAD FLATS: (In a singsong voice) This is a song we wrote for the tourists...

NED HEAVENRICH: It’s changed since we've been here from an industrial economy to a tourist economy, which has benefited us a lot. More venues and restaurants and stuff like that have sprung up. And they are more festivals.

LARRY MOORE: You know it’s a little bit of an irony, but you’ve replaced one kind of industry with another, and it's important how it's done (laughs). You know so... timber, fishing, that is what, I think, people consider the source of a place. Like can you have both? It would be nice to have both. Sustainable everything!

LAUREN MCROBBIE: Increasingly fishers and other workers share what they do with curious visitors.

SARA SKAMSER: I see tourists just lining the docks and they all have this just far away look in their eyes like, "I could do it, I could fish. I could go out there."

You know they just all are, it's just an enamor, it's something I think within all of us because of the fact that we're made of seawater.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Sara Skamser has made her fishing net workshop a go-to spot for educational events and tuna barbeques.

SARA SKAMSER: We do a lot of workshops with laypeople and marine biologist students. And the guys working on the nets just fascinates people. And then we'll have excluders out on the parking lot to show them the different types and jus to inform them because the fisherman are busy, they never tell their own stories. So we're kind of the in between.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: COVID-19 precautions mean that the social life around commercial fishing is on hold. Brownsmead Flats, their last gig was at the FisherPoets Gathering back in February. But when they take the stage again they'll be back to doing what they do best, bridging the worlds of work and play in coastal Oregon.

(Brownsmead sings)

KAYTE YOUNG: This story by producer Josephine McRobbie and public folklorist Joe O'Connell features the voices of Oregon base commercial fishers and seafood entrepreneurs. O'Connell conducted the original research in August 2019 for the Oregon Folklife Network with support from the National Endowment for the Arts.

(Earth Eats theme music)

Have you found us on Twitter? Follow @EarthEats to stay up to date on food and farming news, seasonal recipes, food justice stories and so much more. You can also find us on Facebook and Instagram @EarthEats. We even have a YouTube channel and there's a brand new video produced by Peyton Noblock featuring me in my home kitchen making savory hand pies from scratch. Find that on the Earth Eats YouTube channel or on our Facebook page. That's it for our show this week, thanks for joining us.

RENEE REED: The Earth Eats team includes Eobon Binder, Chad Bouchard, Mark Chilla, Abraham Hill, Taylor Killough, Josephine McRobbie, the IU Food Institute, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed. Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from the artist at Universal Productions Music. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week to Taneisha Henline and Joe O'Connell.