KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana, I'm Kayte Young and this is Earth Eats.

MICHELLE HUGHES: We've been presented with problems today that we've never dealt with before as an agriculture industry, like climate change. And I don't think the approach that we've taken historically is going to work here. As long as I've heard the words "climate change", I have heard that indigenous practice is the solution.

KAYTE YOUNG: This week on the show, we talk with Michelle Hughes of the National Young Farmers Coalition. Three years ago, the organization made a decision to put racial equity at the center of their strategic planning work. Michelle Hughes shares the story of their transformation. And Josephine McRobbie brings us a story about a new web tool that might help oyster farmers better prepare for the rainy season. That's all just ahead. Stay with us. Thanks to listening to Earth Eats. I'm Kayte Young.

KAYTE YOUNG: In North Carolina, storms can shut down oyster harvests for weeks. Josephine McRobbie speaks with a team of researchers at North Carolina State University who have developed a web tool that might help shellfish farmers better plan their rainy seasons.

JAMES HARGROVE: 2018 was probably one of the worst years that we've had. Hurricane Florence came and dumped 30" of rain and shut us down for weeks.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: James Hargrove is an environmental consultant and oyster grower. Like many other shellfish farmers in North Carolina, he leases his growing area from the Division of Marine Fisheries.

JAMES HARGROVE: We have three shellfish locations that we harvest from: Masonboro Sound, Topsail Sound and Stump Sound.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: James is calling from the road. He's often traveling. Growing oysters is like tending a garden. Farmers have to visit their lease areas all the time.

JAMES HARGROVE: You're taking small oysters and putting them in small mesh bags and then when they grow, you move them up in size to a larger mesh bag and we probably handle the oysters and do that, grade them by size, maybe 12 times before we harvest them.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: The state closes lease areas based on the potential for rainfall run off and how it might affect the safety of raw seafood. When Hurricane Florence hit, all of James' leases were closed for several weeks.

JAMES HARGROVE: If we can't harvest oysters, we 100% lose money because it's not like we leave the oysters there. We still have to do farm tests. So, we're still paying for our employees and fuel and other expenses to get to the farm and do the farm related works. It's just we don't make any money.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Along with 300 miles of coastline, North Carolina's seafood industry takes place on bays, sounds and wetlands. It's the second largest estuary system in the country.

DR SHEILA SAIA: For some of the more inland rivers and sounds, those thresholds are lower.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Dr. Sheila Saia is a data scientist and associate director of the State Climate Office in North Carolina. She says that temporary shellfish harvest closures depend on where a lease is located.

DR SHEILA SAIA: So, for example, Newport River, that's near Beaufort. It has the lowest threshold before it closes. So, in Newport River, one of these areas actually has 1" in 24 hours if it rains. The State of North Carolina will close any harvesting that is happening. But then out in the larger estuary, like Pamlico Sound, a larger area, those can be 4" or even just emergency condition.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Closures can be frequent. They can also drag on. James remembers one closure in his growing area that lasted for six weeks, right during the peak season of Thanksgiving.

JAMES HARGROVE: You plant these as what we call a seed, but you expect to have a certain amount ready during the week and you kind of program your planting to have that certain amount, and, so, when you don't harvest that for a month and a half, your whole system kind of gets backlogged and your oysters are growing this whole time and you can grow bigger oysters which sometimes the Half Shell restaurants don't really want. So, in total, I think between five growers up there, there was probably at least 100,000 oysters that didn't get sold.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: So, watching for incoming storms is critical to operations.

JAMES HARGROVE: It's a huge factor in doing business in the shellfish industry.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Dr. Saia says that most shellfish farmers rely on a variety of tools to keep informed about weather-related closures.

DR SHEILA SAIA: A lot of farmers are aggregating huge amounts of data.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: They use everything from weather apps to the Department of Marine Fisheries site to local news outlets, but there's not much that's tailored to their industry. Parsing data to make a business decision is a challenge. When Dr. Saia was a post-doc at North Carolina State University, she was working with her supervisor, Dr. Natalie Nelson who studies predictive modeling and water quality to assess needs for shellfish growers.

DR SHEILA SAIA: She had some conversations with one very active person in the shellfish agriculture industry. So, that connection led to them brainstorming, if a tool is necessary. And in this case, yes. Then, what could it look like and how could we use openly available data from the National Weather Service and these programming languages that are open source to sort of build something like this?

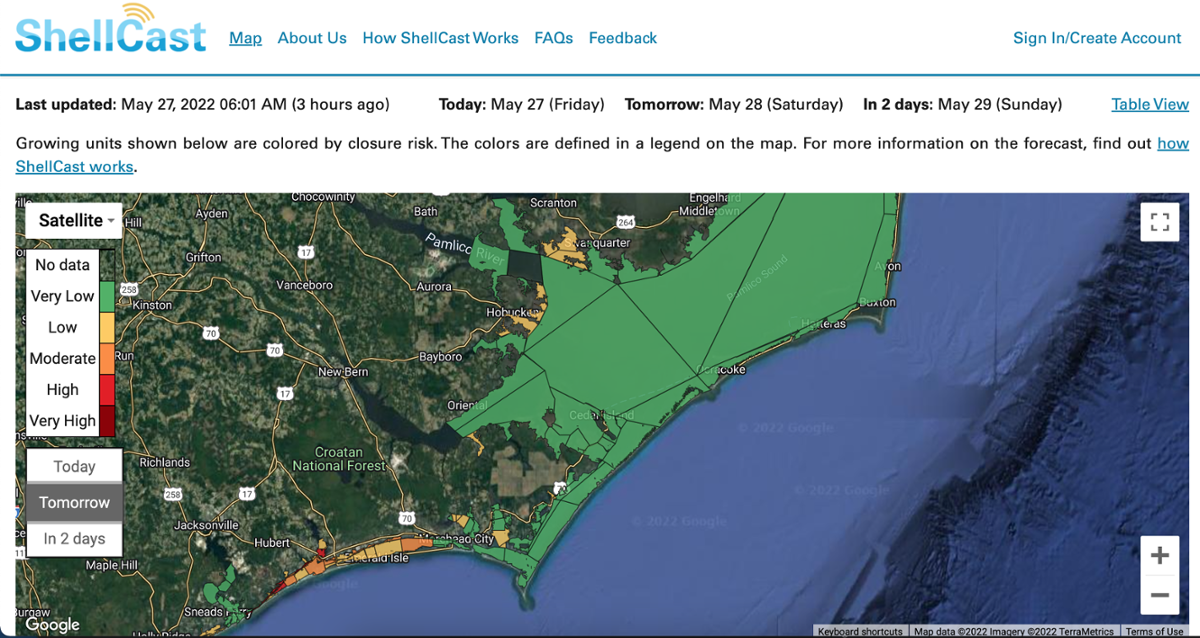

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Recently they released a pilot of ShellCast, a web-based application that shows lease areas, their current status and their potential for closure in the next few days. Dr. Saia is showing me the web app at the local public library.

DR SHEILA SAIA: And so you can see, we have a storm coming in and tomorrow it looks like there's going to be a lot of rain along the coast.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: The application uses publicly available weather data, both forecasted and historical, as well as rainfall thresholds of different lease areas to predict the possibility of closure.

DR SHEILA SAIA: So, we have this base map that shows the satellite imagery and then the polygons for these growing areas and then the point data for the leases. That all came from the Division of Marine Fisheries.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: They solicited user feedback with shellfish growers along the coast before launching the app.

DR SHEILA SAIA: One of the most important features for some of the growers that we talked to was that ability for them to get notifications. So, for tomorrow, this area is going to be very high, so it'll close. So, at 7:00 a.m. in the morning, they would have received a text that says, "Tomorrow it's very likely that your area will close." So, then they can say, "Oh, okay, I need to go out and harvest," or, "I'm going to wait till after the storm passes," and just wait on it.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Predictive modeling for weather isn't able to create a perfect system and the coast is an especially volatile area.

DR SHEILA SAIA: This is like Weather 101, I guess, for North Carolina, like meteorology people, but you have these storms in the cooler months that they're really coming from out west and it's very easy for us to predict what's going to happen in terms of rainfall, but in the summer, we have a lot of very localized spin-up storms that just form on the coast and they're very hard for us to predict. People that live out there, they're used to that, but capturing that in this application is quite hard.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: James Hargrove participated in the pilot program. He agrees that one application won't solve all the oyster harvest problems associated with high rainfall in the Carolinas.

JAMES HARGROVE: Like everything, trying to predict the weather, you're trying to predict the weather.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: But he'll take all the help he can get.

JAMES HARGROVE: It's another tool in the tool belt and it's not the only thing that we use, but it's great to have something looking at multiple parameters to tell me to pay attention. So, we 100% use it. It's an awesome tool.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: For WFIU's Earth Eats, I'm Josephine McRobbie.

KAYTE YOUNG: Kayte Young here. This is Earth Eats.

KAYTE YOUNG: Since the police murders of George Floyd and Brianna Taylor and the protests and outcry that followed, we've heard a lot about diversity, equity and inclusion policies. We've heard statements from corporations, organizations, brands and universities about a renewed focus on racial justice.

KAYTE YOUNG: Much of the time, these statements are just words. They show up on Twitter feeds and take up space on websites but often very little changes in the staffing and leadership or in policies that might make a real difference in the lived experiences of black, indigenous and people of color or BIPOC communities.

KAYTE YOUNG: When I received a newsletter from the National Young Farmers Coalition in 2021 about their strategic planning and new guiding principles focused on racial equity, I was skeptical. I went to their website expecting to see the predictable promises and platitudes and commitment to racial diversity with a token photo or two of farmers of color in a field.

KAYTE YOUNG: What I found instead surprised me. Most notable on first glance was the diversity of the staff and board of directors. That got my attention, because I'm familiar with the challenges of shifting an historically white led organization into a racially diverse staff, especially in the agriculture sector.

KAYTE YOUNG: As I dug deeper and started reading the extremely thorough and far reaching accountability report released in 2021, I knew I wanted to talk with the author listed on the report.

MICHELLE HUGHES: My name is Michelle Hughes. I currently serve as operations and impact director for the National Young Farmers Coalition. I live in Washington, DC. We have our office in DC here, so, I live in Washington, DC, near our DC office.

KAYTE YOUNG: I started off our conversation by asking about her background and how she got into farming.

MICHELLE HUGHES: I don't have a long history with farming, but it's certainly a passionate one. I always had an interest in animals and animal husbandry for most of my life and spent a lot of time working in small animal hospitals. I then discovered large animal medicine and food animal medicine as something that had a really significant impact as someone who was looking at my professional career, maybe to become an veterinarian at the time. So, I started working in large animal medicine, at first with just goats and sheep, and then I started working with pigs and started learning more about the pork industry and became a hog farmer, kind of without knowing it, after I graduated from college. So, I went to Haverford, which is situated in the suburbs of Philadelphia. So, it's 25 minutes from the city, but also means that it's not too far from many farm counties in Pennsylvania.

MICHELLE HUGHES: So, I became very connected with the University of Pennsylvania. They have a veterinary school and they also have a large animal facility. So, I worked at their large animal facility. I did a variety of things including veterinary medicine, animal husbandry and also some research on different types of farrowing environments, so how piglets are birthed and where they're birthed. So, I did a lot of that and the facility that I worked at was quite large. So, we had upwards of 800 pigs, I would say, at a time, mostly momma pigs, but we did have a lot of piglets and some boars too, which are older male pigs. So, I worked at a facility that was very large. It was just a few of us working there full time and it was tough. It was definitely some of the most difficult work I've ever done and I faced many of the barriers that young farmers face that we work for at Young Farmers every day.

MICHELLE HUGHES: So, that's kind of how I got into farming. It was really by way of animal agriculture and an interest in having an impact on the food system. I just realized that agriculture and farming was really the way that I wanted to do it, even though I wasn't from a farm family or didn't really come from a farm background. It was definitely a transition, but a really welcome one and it really brought to together a lot of my interests.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes, that does sound really hard. Was it hard as in hard labor or just hard?

MICHELLE HUGHES: Yes, I think it was hard in all the ways. It's physically difficult. Large animals are very strong. So, it's physically difficult, because you're trying to get them to do things that we want them to do and move in places and ways that we want them to, that we think will benefit them. So, that's really difficult, because pigs, especially, can be very stubborn and very strong willed. And they're very big. We're talking about 300 lb animals. So, it really is a very serious physical profession. But it was also tough for me, I think, mentally because I was very isolated. Kennett Square, Pennsylvania isn't a place where I met a lot of other farmers that looked like me or that were as young as I was. I had just graduated college, I was very young, very early in my career, not a lot of work experience and I was very intimidated by the agriculture industry.

MICHELLE HUGHES: Certainly on a daily basis, but also just breaking into the industry itself seemed really intimidating, because when you farm, you work directly the federal government and that felt like, at the time, an institution that I hadn't felt a lotta trust with and also, didn't have a lot of experience working with. So, it was extremely intimidating to see a community of people that were very connected and all had that kind of institutional knowledge that I just didn't yet. So, yes, it was tough. It was tough. But I love farming still. It was also the most regenerative time of my life. So, yes, I can still say that.

KAYTE YOUNG: How did you find your way into your roles at the National Young Farmers Coalition? But it might be useful to just say a bit about what the organization is and what they do.

MICHELLE HUGHES: I actually started with Young Farmers as a member myself. The purpose of Young Farmers really has always been to service new, young and beginning farmers. I am sure I don't need to tell you the average age of farmer is reaching 60. And so we primarily service farmers under 40, that's usually who we hear from, usually who's tapping in to our services, but usually in their first ten years of farming. Our vision is a just future where farming is free of racial violence, accessible to communities, oriented towards environmental wellbeing and concerned with health over profit. So, there's a lot in there and our mission, the how, is we really work to shift power and change policy to equitably resource the next generation of working farmers.

MICHELLE HUGHES: We have our internal programming which is the part of the organization that I work mostly with, the core operation. So, that includes general operations and people and human resources, processes, development, finance. But then there's our policy and advocacy work, so that's where our work starts to become external. And there's also our organizing and field work, which is also very external. So, organizing and field work and policy and advocacy are very much intertwined and the operations team kind of supports that work.

KAYTE YOUNG: Michelle points out that the internal operations work is important, because of the way it trickles out into the communities they serve.

MICHELLE HUGHES: So, our vision and mission really starts at the heart of our organization, which is how we treat our people that we interact with day to day, our staff, and then how they interact with our farmers, colleagues, funders, other major stakeholders.

KAYTE YOUNG: It sounds like they're mostly under 40, but they could be new farmers, but maybe a little bit older?

MICHELLE HUGHES: Definitely. Yes, I think there are some farmers in our network who are farming as a second career. A lot of folks, who don't have generational wealth or are not from a farming family, have to build some of the financial capacity that it takes to be a farmer full time. So, a lot of people do it as their second career, because they've had the time, in a different industry perhaps, to save money to buy land and to be able to work a profession that isn't exactly as lucrative as a lot of other professions that currently exist.

KAYTE YOUNG: Right. So, the organization is basically about supporting the next generation of farmers.

MICHELLE HUGHES: Right, it's about keeping farming alive, really, because the reality is that the next generation of farmers has to be more diverse, more innovative and has to be more in tune to climate change, more in tune to racial justice and that's the future of agriculture, or, at least, that's what we believe at Young Farmers. So, it's hard to see one without that. So, that's what I mean. I do think that the fate of the future of the agriculture industry does lie with the next generation.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, do you want to say a few words about how you found your way to this organization and how you got involved?

MICHELLE HUGHES: There's a conference that's held for farmers that work in Pennsylvania called Pasa. It's a sustainable agriculture conference. And I met young farmers, staff at that conference almost six years ago now and just felt like it was the first place in farming that I belonged, honestly. I had a hard time fitting in, I think, in the industry up until then. And, I mean, I chose hog farming which is not exactly the most diverse set of farmers in the industry. So, it is what it is. I had met Sophie and Holly and a couple other folks at Pasa when Young Farmers was still ten staff. So, this was in 2016 and I just felt like, wow, this is a place that actually cares.

MICHELLE HUGHES: I'd gone to a few local farmer groups and other organizations or farmer chapters around and I just didn't feel the same camaraderie. I didn't feel the same openness. I didn't feel the same welcomeness. So, that was the beginning for me, was just the relationship development. I kind of just kept my eye on Young Farmers. I didn't really know where my career was going to go. I knew I was going to stop farming. I was debating getting a masters degree. I was still thinking about going back to veterinary school. I had a lot on my mind and Young Farmers was an organization that really made me feel like I could continue to work in agriculture.

KAYTE YOUNG: She started out part-time as an organizer, setting up round table discussions in New York State ahead of the 2017 Farm Bill. The National Young Farmers Coalition does a lot of organizing around the Farm Bill, since that's what sets agriculture policy at the national level for four year stretches of time. We'll have more on that later.

MICHELLE HUGHES: I decided to stick around and I also decided to get a masters degree. I really wanted to know everything I could about the food system and why it was so hard for me to get where I wanted to be within it. So, I got a masters degree from New York University in food studies, and at the same time, kept working at Young Farmers as an executive assistant and kind of a special projects manager with our founding executive director on a variety of projects that really broadened my understanding of the work that a non-profit organization could do on behalf of young farmers. By the time I was finishing my degree and I was looking for a full time position, Young Farmers was hiring a federal policy associate and I did feel like I had explored enough parts of the organization that I was interested in working in policy specifically.

MICHELLE HUGHES: I did advocacy on Capitol Hill three days a week before the pandemic and fell in love with the development of policy that could have equitable change. I worked on the federal policy team, I feel like at a time when we couldn't have pushed forward what we're able to be a bit more bold about today.

KAYTE YOUNG: Michelle then moved to internal policy at Young Farmers. She recognized that she could play an important role in the organization's upcoming transformation. In 2019, when new co-executive directors came in, Sophie Ackoff and Martín Lemos, they came in with a mission to strengthen the racial equity analysis across the organization. This work had begun at Young Farmers as early as 2016. For example, in their racial equity statement from 2016, they admit that though their mission involves removing structural barriers for the next generation of farmers and ranchers, they have focused on land and capital, but have failed to address race, an issue that often outranks any other for young farmers of color.

KAYTE YOUNG: They go on to say, quote, "When we tell the story of why our work matters, we frequently reference the devastating pace of small farm loss in this country, but rarely do we discuss the systemic dispossession of land from black farmers and the lasting impact of that stolen inheritance for their children and grandchildren. We don't discuss the lack of mobility for the millions of Hispanic farmers who are now laboring for others, nor the original violence against Native Americans who are now relegated to a fraction of what was once their land." End quote.

KAYTE YOUNG: The organization made a decision to put racial equity at the center of their strategic planning work and to center black, indigenous and other people of color, BIPOC, farmers, partners, board and staff. In doing so, quote, "We strive to both confront the historical and ongoing violence against BIPOC communities, intrinsic to our food system and to orient agriculture toward the realization of justice and a world defined by equitable outcomes. Racial justice is foundational to making farm policy that honors our vision for the future." End quote.

KAYTE YOUNG: This is Earth Eats, I'm Kayte Young and I'm speaking with Michelle Hughes with the National Young Farmers Coalition. We'll talk more about that racial equity analysis and the organization's transformation after a short break. Stay with us.

KAYTE YOUNG: This is Earth Eats, I'm Kayte Young.

MICHELLE HUGHES: I don't know that we expected it to turn into what it did. I think we thought we were going to do a general comb-through and maybe a few redesigns but, once we had done the first identification of gaps, we just realized we had so much work to do and so I really pivoted full time to working on internal policy at Young Farmers.

KAYTE YOUNG: That's Michelle Hughes, she's the operations and impact director at the National Young Farmers Coalition and she's talking about the transformation that the organization has been moving through over the past few years.

MICHELLE HUGHES: Our racial equity transformation began in so many different places. We had people speaking out, farmers, partner organizations and staff, speaking out before we officially started our racial equity work publicly. The 2016 racial equity statement came from staff who felt passionately, who felt compelled, who felt moved to speak on what was happening in the world. Then the same for 2020. We had gotten feedback from a lot of members of the coalition that the organization really did need a transformation like this long before it started. So, it really did, it began from the people that really wanted to see the change. And as I said, the new leadership presented just a new opportunity for bigger steps on racial equity.

KAYTE YOUNG: Those bigger steps started with a framework. The framework includes cultivating a shared understanding within the organization, which means getting everyone on the same page and developing a shared language for talking about race and equity. The second piece they call designing with intention. And this is where they examined all of their programming to find the gaps, to see where they were perhaps failing to address the concerns of BIPOC farmers. They were also examining their internal human resources and overall operations.

KAYTE YOUNG: The third part of the framework is accountability. Michelle Hughes is the lead author of the organization's accountability report, though she's quick to point out that many others worked on it with her. It's a very thorough document that does not shy away from naming specific areas where the organization got it wrong and outlining the steps they are taking to correct their mistakes. Honestly, I've never seen anything like it and I recommend checking it out if you have any interest in the nuts and bolts of what this kind of organizational change can look like. You can find it on their website, youngfarmers.org. Michelle shared some examples of their work.

MICHELLE HUGHES: One of the biggest changes was our recruiting efforts. I think for a long time we relied on kind of the same channels and places to recruit talented staff and we realized in our impact assessment that, that was an area where we were really lacking and might keep us from reaching our strategic goals.

KAYTE YOUNG: The results of their efforts in recruiting have really paid off. The National Young Farmers staff is a remarkably diverse team in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation and class background and they are guided by a majority BIPOC farmer board of directors.

MICHELLE HUGHES: Another great example that I always love to bring up of success stories is convergence. We have an annual gathering of farmers every year where we have just basic programming that historically would have kind of a set-aside in programming for BIPOC farmers, but in recent years has become a space that is majority BIPOC. So, convergence has kind of revamped its programming to attract the people that we actually want to go to convergence. Then, another example I give is the land work. Our land campaign has gone from a department that really focused on private land ownership. Holly, our land access director, has taken it from this traditional approach, very much the way that a traditional white farmer would acquire private land and farm, to really talking a lot more about the different options for shared land and even public land. So, that's another place where I see our work growing and I always bring up the land work, because it's really the backbone of our work and the number one thing that a farmer needs to succeed.

KAYTE YOUNG: Can you talk about what caused the organization to really identify that the direction that the organization needed to move was towards centering racial equity? How did you come to that and what are some of the issues that black, indigenous, people of color, farmers face?

MICHELLE HUGHES: Yes. As I mentioned, definitely feedback. We listened to our audience. We listened to the people in our spaces tell us that they needed more designated space, more programming that actually talked about the issues of BIPOC farmers. I think that they knew before we did that the future we were trying to promote is not possible without some racial equity efforts. We envision a future free of racial violence. It's optimistic. As a person of color, I will just tell you, I mean, I look more at racial equity as something that I want to make progress on in my lifetime, rather than a destination. But I also envision a future free of racial violence. I think that, with more diverse staff, more talented staff, staff that have expertize in areas that we didn't used to cover, that we now cover, we've just learned about all of the diversity in agriculture that actually exists in all the places that we weren't giving enough attention.

KAYTE YOUNG: It's something that we've definitely talked about on this program before, but for those who either aren't in the farming space or for white folks who are in the farming space, might not have given much thought to what some of the barriers are for people of color too.

MICHELLE HUGHES: Yes, I think there are a lot of issues that BIPOC farmers face. Some are not very different from issues that white farmers face or really any other farmer. But the issues disproportionately affect farmers of color. So, the issues that all farmers face, you can assume are either doubled or tripled for folks who identify with an identity that's been historically marginalized in farming. There's a lot of reasons for that, but a good example that I can give of how issues in farming disproportionately affect young farmers of color, is definitely land access. It's very expensive and it's expensive in terms of finances, but it's also expensive in terms of knowledge. Land is not something that they're making any more of. The amount that we have is the amount that there will be and that means that there is a very strategic fight over that land.

MICHELLE HUGHES: So, information is really important and so not being a part of a farming community, not being from a farming community, not being a second, third, fourth generation farmer, means that you don't have any of that. That is more true for farmers of color whose families have been displaced, have been put off the land, and honestly have been just economically exploited. I think that in the history of the farming industry and agriculture, we see so many places where the agriculture industry either stripped a community of color of land or labor or expertize or resources of some sort.

MICHELLE HUGHES: So, you couple that with, today, the reality that generations later there are people of color who want to continue farming. They don't have that history to rely on. They don't have the years and generations of wealth, of knowledge, or resources, maybe even of land to continue that chain. So, it's almost like many farmers of color are starting from ground zero. I want to name that there are some farmers of color who, especially in the south east, live on family land. I don't want to give the impression that there are no farmers of color that are third, fourth generation farmers. They exist. But the numbers are dwindling every year. The number of farmers of color, the number of black farmers specifically, just continues to decrease.

MICHELLE HUGHES: All of that is to say, it's the generational wealth piece that I think is just really difficult for farmers of color, and student loan debt. I think we could have a very similar conversation for both of these. Student loan debt can be really paralyzing if you're trying to start a farm business, because it's often hard for you to leverage more capital if you have loans out already that are significant. I am not a student loan expert, but I used to work on our student loan portfolio and the number of students of color that need student loans is disproportionate in comparison to the number of non-students of color that need student loans. So, it is a very complicated sequence of events that has gotten us to where we are. So, it's going to take very, very creative and innovative solutions to change these things.

KAYTE YOUNG: You have touched on this already, but I would love to just hear you articulate it again. What's at stake for food in farming in our nation if these issues of racial equity are not addressed? What is the danger of not changing course or just of your organization not changing course?

MICHELLE HUGHES: Yes. I don't know, everything, it feels like to me.

KAYTE YOUNG: Feeding the nation.

MICHELLE HUGHES: I know. I mean, I think that things that we've seen in history would just continue. Logically, I think if we don't change, we'll just have more of the same. We'll more of the same erasure and displacement that I was talking about, that we've seen throughout history. But beyond that, I think an interesting perspective is that the market will suffer, the agriculture markets themselves will suffer, which there are many of. I mean, the industry for agriculture is huge in the US. So, it'll suffer without the contributions of farmers that bring perspective to the way that we've been doing agriculture for so many decades. We've been presented with problems today that we've never dealt with before as an agriculture industry, like climate change, and private land is starting to become monopolized, truly monopolized.

MICHELLE HUGHES: I don't think the approach that we've taken historically is going to work here and I don't need to be the one to say that. Especially with climate change, as long as I've heard the words "climate change", I have heard that indigenous practice is the solution. So, to me, that in and of itself, if we don't have those people present, because they're the holders of that expertize, we can't actually solve those problems.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, you're listed as the author of the Young Farmers accountability report. Can you tell me what that is? I know that it's a complicated document and you did outline a little bit of it, but I would just like to hear what it's trying to do and how you went about that.

MICHELLE HUGHES: The Young Farmers accountability report is basically a chronicle of our racial equity work to date, and because it was the first chronicle, we plan to publish more accountability reports, but because it was the first, we started it really with a little bit of background on the history of Young Farmers. What you won't read in the report, is that Young Farmers, when it was founded, was considered a majority white organization, is still considered a historically white founded organization, but, in my opinion, just is no longer a majority white organization. It's statistically not a majority white organization any more and there are enough, to me, leaders of color on staff and on our board that I don't think Young Farmers can be categorized as white led any more.

MICHELLE HUGHES: I think, saying that, it's erasing the work that I've done, it's erasing the work of the people that have come before me who walked so I could run. It was a moment for us to say, okay, this is where we came from, these were the mistakes we made, here's what we're doing now and here's where we're going. And from here moving forward, we are making a commitment to not do these things any more, but also to live into who is actually a part of the Young Farmers community. I think, for some time, especially when you start out as an organization that creates a reputation that it is led by people in farming who are white and think in a way that is only helpful to them perhaps, I think it, it had that perception, it's very hard to get out of that. It's very hard to get out of that reputation. Whether it was valid or invalid, we still had to deal with the consequences of some people seeing us that way.

MICHELLE HUGHES: I feel like the accountability report was a moment for me to bring the work that I'm doing to light and the work that so many staff are doing to light, to say to our farmers, first of all, we take responsibility for what's happened, but also we're starting a new chapter.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes, a couple of things I wanted to say about it, just as an observation. The word "accountability", it's just something that's so lacking in our society, in our political world certainly and in the business world and just everywhere. It just feels like nobody's taking accountability for mistakes that have been made and I've found it so refreshing to see some of that in the parts of the report that I read, where even leadership was saying, we did this and that was the wrong direction. I just think that's just very rare. Usually people just want to get to the moving on phase and don't want to pause at the accountability part.

MICHELLE HUGHES: Yes, it definitely doesn't feel great, the process of improving, healing, racial reckoning. It hurts. It's not a process that we go through and there's no bumps. There's a lot of bumps. It's not linear. It's hard to control. So, it's difficult, because we put it in this container of a non-profit organization where we expect it to act one way. So, yes, it was very difficult, but I hope, and it did for me, it felt really cathartic and relieving to be able to share it with the public. Also, just to be able, as I'm sure other institutions have felt, the liberation in being able to say, we made these mistakes, was just very surreal for me. Even though I hadn't been a part of all of them, the organization is still taking responsibility as the power that it has as an institution, and that is something that I really wanted to get behind and be a part of changing.

KAYTE YOUNG: The other thing that I wanted to say, just about the organization not being white led, or you couldn't consider it to be a white led organization anymore, is that I think that that's probably what got my attention more than anything when I first saw the announcement about the kind of revisioning of the organization. I went to the website and I started looking at the leadership and I saw it that it wasn't white led anymore and I felt like, wow, that's a real change. There are many organizations that are saying that they're doing things, but the leadership isn't changing, and it doesn't mean that they can't do anything, being white led, but it's not the same kind of change. So, I just wanted to remark on that, that it really felt like, oh, this is different. This isn't just people saying, we want to be different, we want to be more racially diverse, it was actually making that happen.

MICHELLE HUGHES: Yes. I appreciate that. Thank you. I have to give most of the credit to our board development, to the co-executive directors. I mean, Sophie and Martín, as I'm sure you know, executive directors are part of the board development process and that was one of the things that was on their list. They gave a presentation to staff before they came on as co-EDs of, here's all the things we want to do, and one of the big ones was, we want to make sure that the people that we want represented on the board are on the board. And I think it's quite underestimated actually in the non-profit world, of some of the folks that we service, just how important and impactful a board of directors of a non-profit actually is.

MICHELLE HUGHES: I think that, that is because the board of directors of a non-profit are generally kind of invisible and so, to everyone else, you might think it's no big deal, but when you're in it and in a senior leadership position, executive team, co-executive directors, those people all report to the board of directors. So, it is very important that we have people on that team that are thinking about the work the way that we are as staff.

KAYTE YOUNG: Can you point to some of the changes that have already been made as a result of some of this re-organization and transformation work?

MICHELLE HUGHES: Yes, definitely. I think so. I mean, I think our relationships have become a lot more honest with all of our stakeholders, for certain. Also, we are invited to tables that we weren't invited to before. I secured a seat on the USDA Equity Commission, sub-committee on agriculture, which is still very surprising to me, but I'm trying to live into my glory.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, what is that? Can you explain what that is?

MICHELLE HUGHES: Yes. So, the Equity Commission at USDA is a body that was created from an executive order in the American Rescue Plan by the Biden administration. So, I am not a member of the equity commission. There's a 15 member governing body of a number of sub-committees. There's a sub-committee, for the Equity Commission, on agriculture specifically that was stood up late February. So, we've been meeting for a few months. And they're also standing up a rural development sub-committee as well. So, what is the point of this? We are doing an analysis, very much like the analysis that we've done at Young Farmers. We're doing an analysis of historical recommendations and current recommendations on a variety of topics that we think could increase equity at USDA.

MICHELLE HUGHES: So, without our equity work and our transformation, we definitely wouldn't have been able to hold space like this. I think we got on it because we did a mini version of some of the work that they want to do and have done. This isn't the first ever USDA equity effort. There's been bodies. We're not the first. But it feels different. It feels like really making waves.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes, I think that's very exciting.

MICHELLE HUGHES: It is, yes.

KAYTE YOUNG: It feels like the ability to really make structural change, if you're going to be involved at that level, and because you had done that work already, you were kind of ready. You had something to bring. You have some experience to bring to that. That is very exciting.

MICHELLE HUGHES: It is and it's exciting that USDA is invested the way that they are in the process as well.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, speaking of governmental bodies, there will be a new Farm Bill in 2023 and I know that in 2017 that Young Farmers had an agenda and policy, federal policy recommendations. Is that something that you are moving towards for this Farm Bill as well?

MICHELLE HUGHES: Absolutely, yes. The Farm Bill is the thing. So, we just finished, wrapped the National Young Farmers survey and we got over 10,000 responses. It's going to be really helpful to us in advocating for the changes that we wanna see in the Farm Bill in 2023, because it is data that is honestly the driving force behind what challenges young farmers are really facing and the National Young Farmers survey is the most comprehensive census that exists of young farmers. I don't want to put USDA to shame, but there are more young farmers that take our survey.

MICHELLE HUGHES: Our biggest reach in the Farm Bill coming will be definitely land access, affordable land access for young farmers. We'll be hosting a fly-in where we'll bring 100 plus farmers to advocate to members of congress about the changes we want to see in the Farm Bill. These are gigantic projects for young farmers. So, we're putting all the resources and time and capacity that we have into the Farm Bill, because we have a limited amount of time to continue to have an effect on federal policy. Maybe we don't, but it certainly feels like we have a time limit right now. In the time that we do have, we have to focus everything concentrated on the thing that's going to have the most lasting impact, that won't be changed. We don't want programs that we create for BIPOC farmers to be able to be attacked.

MICHELLE HUGHES: But there, you can have that kind of impact without flying to DC and going to the Hill, right? We have actions that we send out to people via text that are very simple. There are some very small actions you can take.

KAYTE YOUNG: That seems like a great place to wrap up an episode focused on the National Young Farmers Coalition. They are largely an advocacy organization. They bring forward the concerns of young and beginning farmers and work with policy makers to implement change. They're educating law makers about the issues that farmers face, but they also work to educate the public to pressure law makers to act on behalf of farmers. That's a role that any of us can play. You can find links to all of the documents and guiding principles for National Young Farmers Coalition on our website, eartheats.org, and you can learn about current campaigns and ways to get involved by going directly to their website at youngfarmers.org. I've been speaking with Michelle Hughes.

MICHELLE HUGHES: Kayte, thank you so much for this.

KAYTE YOUNG: Thank you so much. She's the operations and impact director at the National Young Farmers Coalition. She's the author of the organization's accountability report and has played a huge role in guiding the Young Farmers Coalition through their racial equity transformation. Thanks for listening. That's our show this week. I'm Kayte Young and this is Earth Eats. We'll see you next time.

RENEE REED: The Earth Eats team includes Eoban Binder, Mark Chilla, Toby Foster, Abraham Hill, Josephine McRobbie, Daniella Richardson, Payton Whaley, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week to James Hargrove, Sheila Saia and Michelle Hughes.

RENEE REED: Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from the artists at Universal Production Music. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey.