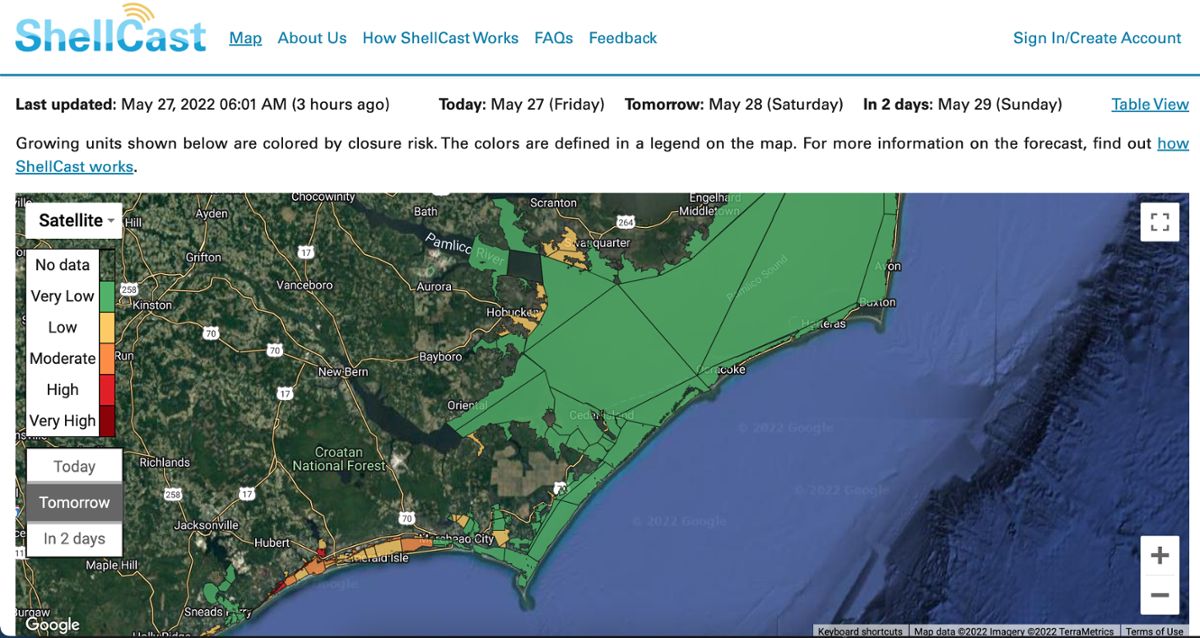

Shellcast is a web-based application that shows lease areas, their current status, and their potential for closure in the next few days. (shellcast)

James Hargrove is an environmental consultant and oyster grower. Like most other shellfish farmers in North Carolina, his company Middle Sound Mariculture leases its growing areas in Masonboro, Stump, and Topsail Sounds from the Division of Marine Fisheries. Shellfish farming involves frequent visits to lease sites. “We probably handle oysters and grade them by size 12 times before we harvest them,” he says.

The state closes lease areas based on the potential for rainfall runoff and how it might affect the safety of raw seafood. James remembers one closure in his growing area that lasted six weeks, right during the peak season of Thanksgiving. “When you don't harvest that for a month and a half, your whole system kind of gets backlogged,” he says. Planting “seeds” to have a certain number of oysters ready at a certain time is a delicate operation. “Your oysters are growing this whole time, and you can grow bigger oysters [but] sometimes the half shell restaurants don't really want [them].” Between himself and several other nearby growers, he estimates they lost 100,000 oysters during that Thanksgiving closure.

James explains that the loss of product is worsened by the fact that farm operations still have to happen while harvest closures are active. “It's not like we leave the oysters there,” he says. “We're still paying for employees, and fuel, and other expenses to get to the farm and do the farm-related work. It's just we don't make any money.”

Along with 300 miles of coastline, North Carolina’s seafood industry takes place on a maze of bays, sounds, and wetlands. It’s the second largest estuary system in the country. Dr. Sheila Saia is a data scientist and Associate Director of the state climate office in North Carolina. She says that temporary shellfish harvest closures depend on where a lease is located. Some more inland rivers and sounds close for harvest based only on an inch of rain in 24 hours. “But then out in the larger estuary like Pamlico Sound, it can be four inches, or even just emergency conditions,” she says. Dr. Saia says shellfish farmers aggregate huge amounts of data to plan their operations. They use everything from weather apps to the Department of Marine Fisheries site to local news outlets to plan for closures. But there’s not much that’s tailored to their industry.

While Dr. Saia was a postdoc at North Carolina State University, she was working with her supervisor Dr. Natalie Nelson, who studies predictive modeling and water quality, to assess needs for shellfish growers. “She had some conversations with one very active person in the shellfish aquaculture industry [and] that connection led to them brainstorming [about if] a tool was necessary,” she says. The answer from growers was affirmative. Recently, their research team launched Shellcast, a web-based application that shows lease areas, their current status, and their potential for closure in the next few days. The application uses publicly available forecasted and historical weather data, as well as the rainfall thresholds of different lease areas, to predict the possibility of closure. The web application was built with open source software, and uses locational data shared by the Department of Marine Fisheries to map out lease areas.

The NCSU researchers solicited user feedback with shellfish growers along the coast before launching the app. Dr. Saia explains that it was important for growers to be able to receive notifications while out on the farm, in order to plan their week. But predictive modeling for weather isn’t able to create a fail-proof system, especially in a volatile area like the North Carolina coast. “In the summer, we have a lot of very localized spin-up storms that just sort of form on the coast, and they're very hard for us to predict,” explains Dr. Saia. “Capturing that in this application is quite hard.”

James Hargrove participated in the pilot program. He agrees that one application won’t solve all the oyster harvest problems associated with high rainfall in the Carolinas. “Like everything, trying to predict the weather, you're trying to predict the weather,” he laughs. But he’ll take all the help he can get. “It's not the only thing that we use, but it’s another tool in the toolbox. It's great to have something looking at multiple parameters to tell me to pay attention.”

Listen to this story on this episode of Earth Eats.