(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington Indiana this is Earth Eats and I'm your host, Kayte Young.

MICHELLE PORTER: How to make gravy, how to make mashed potatoes and that stuff just real simple that most of cookbooks don't have in them because it's just the simple stuff.

KAYTE YOUNG: This week on our show we hear about a basic cookbook from a bygone era. We have an audio postcard from an expat in Japan at a Thanksgiving-like feast, and chef Freddie Bitsoie from the Mitsitam Cafe in the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C. shares recipe and talks about native cuisines. All that and more coming up in the next hour here on Earth Eats, so stay with us.

(Transition music)

Earth Eats is produced from the campus of Indiana University in Bloomington Indiana. We wish to acknowledge and honor the indigenous communities native to this region and recognize that Indiana University is built on indigenous homelands and resources. We recognize the Miami, Delaware, Potawatomi, and Shawnee people as past, present, and future caretakers of this land.

Renee Reed is here this week with Earth Eats news. Hi Renee.

RENEE REED: Hello Kayte.

Dry summers like many parts of the Midwest saw this year challenge the corn crop. But farmers have high tech tools to lessen the impact, including specially bred seeds and soil management practices. A new study has found that as good as technologies are they have the downside of minimizing the impacts of climate change. David Lobell of Stanford University led the study.

DAVID LOBELL: What we've found with new technologies is more than anything they help you take advantage of good weather and so we can't look to technology to save us from bad weather.

RENEE REED: The way to prepare for that he says is to mitigate climate change. That includes on farm practices like soil conservation but must also include broader efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The study appears in the journal Nature Food.

New research is looking at how the controversial weed killer Dicamba is spreading. This time research is focused at the molecular level. Researchers at Washington University in Saint Louis are examining how Dicamba molecularly bonds with other chemicals sprayed at the same time. Some combos might add to the weed killer's stripped way from the intended fields. Kimberly Parker is leading the study. She says increasing the knowledge of bonds in Dicamba is a first step.

KIMBERLY PARKER: Ultimately the work we're doing to build a better molecular picture I think would hopefully improve and inform the design of better chemicals.

RENEE REED: Parker says more research will be needed to come up with better options for Dicamba. Her team's initial findings were published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology. Thanks to Jonathon Ahl and Amy Mayer for those reports. For Earth Eats news, I'm Renee Reed.

(Earth Eats news theme composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

KAYTE YOUNG: Though native American food is the oldest cuisine on the continent.

(Guitar strumming music)

It's only started showing up in glossy food magazines and high-end restaurant scene in recent years. Chefs like Shawn Sherman of the sous chef approach native cuisine through foraging traditional ingredients and bringing back the foods his Oglala Lakota ancestors may have eaten. Chef Ben Jacobs is a tribal member of the Osage nation and the cofounder of Tocabe, their place is fast casual native American food with two locations in Denver.

There is not one native cuisine. As the executive chef in the national museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C., my guest Freddie Bitsoie, gets that.

FREDD BITSOIE: Fundamentally what my driving force in my career is all about is to make a pathway for native cuisine.

KAYTE YOUNG: The museum's cafe is called Mitsitam which means "Let’s Eat" in the native language of the Delaware and Piscataway peoples. The menu is crafted to enhance the museum experience by exposing guests to some of the indigenous cuisines of the Americas. And to offer a chance to explore the history of native foods. But there are so many traditions.

FREDDIE BITSOIE: Being the chef at museum for the native American cultures throughout the northern hemisphere, it kind of puts a lot on as far as the explanation, the execution, and the presentation of the foods, because there is that responsibility of trying to present things that are indigenous to different regions of the country and still having to have a solid story, and knowledge of where these dishes came from.

KAYTE YOUNG: If you are native American but have attended a Powwow, you might be thinking about frybread. It's a tasty deep-fried dough made with white flour, often served topped with stewed meat or beans. Though it holds a solid place in many native food traditions today, fry bread has its origins in the mid 1800's when native peoples were forced to rely on government rations of white wheat flour, salt, and water. Frybread is not a traditional food to the people native to north America. It's more of a culinary adaptive response to oppression. But that doesn't mean it doesn't have a place in contemporary native cuisine. Chef Freddie Bitsoie didn't prepare frybread during his recent visit to Indiana University. But he doesn't shy away from it either. He says he'll address the topic in his forthcoming book.

I asked him if he noticed a lot of fusions happening native cuisines.

FREDDIE BITSOIE: Oh yeah for sure. So, when we look at how the food is made, there has to be a way where, like for example, French cooking. Cause I went to culinary school and I was formally trained as a French chef. So sometimes what I do when I cook native food is I cook it with the French technique. So inadvertently that's a fusion in itself. there are some chefs out there that are creating native dishes and native sauces based on French ideas. And there's nothing wrong with that. It's just a matter of how you name it, label it, and say where it comes from.

KAYTE YOUNG: Chef Bitsoie prepared a few recipes for the small crowd gathered in the basement cafe of the Wells Library on the IU campus. He made calabacitas, a dish from Santa Fe featuring squash, corn and peppers. He prepared a salad made from swamp cabbage, otherwise known as hearts of palm. Swamp cabbage can still be foraged in the wild in parts of Florida, and is a historical ingredient in Seminole, Miccosukee, and Calusa tribal diets. Chef Bitsoie also made a dish featuring roasted pork tenderloin, served over a savory bean dish.

FREDDIE BITSOIE: So, this is three bean ragu. And I know ragu is not a native term, but we in the culinary world have our own little secret code words. So, saying ragu means "stewed". Stewed beans is something that is pretty much throughout the native world. People will always have a different variation of it. We get some onions, some celery, and some carrots. Now if you were a French cook you would call this mericua.

Okay so when you're making this particular dish you don't want a lot of caramelization happening.

(sound of sizzling)

So, we're adding the beans. But you don't want to mix too much because your beans are already cooked, alright? these are white beans, kidney beans, and black beans. We can use pintos if you'd like, but don't mix too much because it's just gonna get really mushy. And then I'll start the pork dish.

Alright so we have some cayenne pepper, some new Mexican chili powder, some cumin, brown sugar, some dried mustard, and dried sage. So all these flavors kind of blend together and form a nice rub. So, you're just gonna rub it in, you don't put it... I don't any oil on here because I use the oil in the pan to sear.

Alright I apologize if your eyes get watery or if you start coughing.

(Sound of food sizzling in pan)

Just get all four sides going. And then you put that in a preheated oven at 350. About 20 minutes, 20 to 25 minutes. So, your stew should be stewing up by now. This looks really nice. And as you can tell or probably can see, I rarely make sauce a priority for a lot of the foods that I do because I think it's important to understand that there are some sauces involved with some native foods, but I have to go that distinction between what French food is, and what native food is. With native food it's a little different kind of perspective, a little frame of mind. So, I try to purposely do without the sauce just to prove a point to people and I get to tie them, my French chef friends will say "Well there's no sauce".

KAYTE YOUNG: Nobody in the room that day missed the sauce. Samples of all the dishes were passed around for everyone to taste. After the cooking demonstration, I asked him about the role of food.

FREDDIE BITSOIE: Food is everything. Food can comfort. Food can bring people together. Food can even bring family together and most families don't like spending time together, and if food can do that, trust me, it can do a lot. But in all seriousness, food is actually I think the main conduit of storytelling, especially indigenous food. And I'm not referring to indigenous culture,I’m talking about the foods that are indigenous to certain areas of the world. Not just the U.S. alone but throughout the world, because that's where that particular ingredient is from. That ingredient will always tell the story. And as long as that story is there, it becomes a part of people's culture. Food really has this power.

KAYTE YOUNG: Chef Freddie Bitsoie was a guest of the IU Arts and Humanities Council as part of Indiana Remixed. We have his bean ragu recipe on our website, Earth Eats dot org.

Men have long dominated the farming world. So not surprisingly farm equipment, things like tractors, tillers or hand tools, are designed to be used by male farmers. Female friendly tools are hard to come by and as Harvest Public Media's Dana Cronin reports, with more women farming every year, that presents a safety issue.

DANA CRONIN: Dusty Spurgeon has a love hate relationship with her tractor. She helps run Spurgeon Veggies a small vegetable farm in Rio Illinois along with her mother-in-law. As a woman owned and operated business, one of the biggest hurdles they face is the equipment they farm with.

(Sound of a tractor starting up)

Starting with the tractor. Tractors are often used to pull different implements, for plowing, for planting, or for harvesting. Switching those out is not easy, you often need a lot of upper body strength.

DUSTY SPURGEON: You are pushing this thing forward to fit it onto that part and then you have to get it all the way on which is really frickin hard (laughs)!

DANA CRONIN: Frustrating, Spurgeon uses that word over and over again.

DUSTY SPURGEON: I hate it. I hate it. It makes me feel incompetent, like I can't do my job.

DANA CRONIN: It's not just changing the implements on the tractor, it's everything about the way the tractor is designed. She finds the parking break almost impossible to engage. The fuel tank is located at the top of the tractor, meaning she has to lift a heavy fuel can up above her head to gas up. The tractor also has a safety bar that needs to be up in case it flips. It's a very heavy bar.

DUSTY SPURGEON: Oh... oh my god. (Sounds of Dusty straining to lift the bar). Oh!

DANA CRONIN: Spurgeon says she's lucky that she's taller and stronger than the average woman.

DUSTY SPURGEON: If you were a 5"1 woman trying to like put the roll bar thing up or like or change up the PTO or whatever, I don't know that it would be possible to do, without like major potential for injury.

DANA CRONIN: Many of these features are hard for everyone to use, Spurgeon is the first to admit that. But women are at a particular advantage says Josie Rudolphi who researches agricultural safety and health at the University of Illinois.

JOSIE RUDOLPHI: These were designed for people of a certain weight and certain height, pretty much reflective of the male classification in the United States.

DANA CRONIN: She says farming is already a dangerous job, and for women the potential for injury is high. So some are stepping in to help, Ann Adams and Liz Brensinger owns Green Heron Tools which has trademarked the term 'hergonomic'. Their tools designed for women are generally lighter, have patented grips to accommodate smaller hands and come in a variety of sizes. Adams and Brensinger are farmers themselves and got frustrated with the lack of female friendly tools on the market.

LIZ BRENSINGER: I mean there were companies that painted crappy tools pink and called them ladies' tools, but we couldn't find a single case of tools or equipment in the AG sector that had been scientifically designed to work well for women.

DANA CRONIN: Brensinger says women have always played an important role on the farm, and that role only continues to grow. According to the most recent USDA AG Census data about 36% of all farmers are female, and that number has been steadily increasing for the past decade.

LIZ BRENSINGER: To have women playing this important role and having to use tools and equipment that don't fit them, that aren't going to work as well for them as they need something to, and that might actually hurt them, there's just something really wrong with that picture.

DANA CRONIN: She says this is a public health and safety issue, and until female friendly tools are more widely available, farmers like Dusty Spurgeon will continue to put their bodies at risk to accomplish everyday farm tasks. I'm Dana Cronin, Harvest Public Media.

KAYTE YOUNG: Find more at Harvest Public Media dot org. After a short break we have a conversation about learning to cook from an unusual source, stay with us.

(Music)

How did you learn to cook? Did you learn to cook? Not all of us know how to cook. Some of us can boil spaghetti, fry an egg, warm up food in the microwave, and that's about the extent of it. Some of us were taught by parents or grandparents, home economics classes, YouTube, cooking shows, and some of us even have formal training. Last fall a friend of mine told me about a conversation she was privy to at a meeting in Lawrence County Indiana. It's in southern Indiana. They were talking about home cooking and how people learn to cook.

MICHELLE PORTER: I think the meeting were trying to get people back to realizing that's how they, that’s what they need to do is be cooking at home. And that it's not that hard, it can be simple and trying to figure out ways to reach people.

KAYTE YOUNG: That's Michelle Porter.

MICHELLE PORTER: Residential Arts County all my life and right now I'm a Bono Township Trustee.

KAYTE YOUNG: And you say you've lived there your whole life?

MICHELLE PORTER: When I got married, it'd be 48 years ago, we lived out of Orange County Leipsic for two years and then we moved back so I've always lived in, except for those two years, I've always lived in Bono Township.

KAYTE YOUNG: So you've been realizing maybe some of the people in your township are needing those cooking skills or...?

MICHELLE PORTER: No I think IU called this meeting and they just invited all the trustees, and I went. Actually in most of the people in Bono township actually are country folk and they do cook (laughs).

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay.

[NARRATING] And in that conversation Michelle mentioned a cookbook.

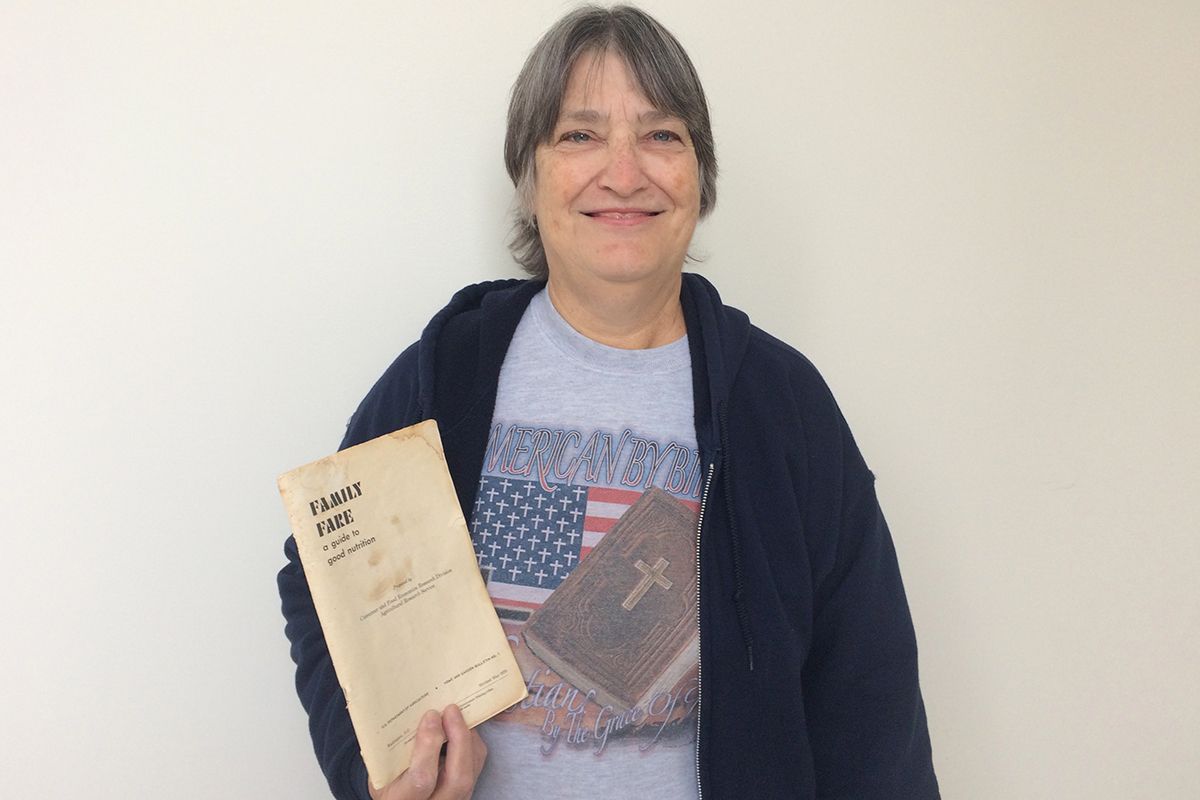

MICHELLE PORTER: When I got married, it'll be 48 years ago next month, Lee Hamiltion sent me this, it's called a Family Fare, A Guide to Good Nutrition Cookbook, and it has just real simple recipes in it that tells you how to make gravy, how to make mashed potatoes, and that stuff, just real simple, that most cookbooks don't have in it because it's just the simple stuff.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay so some of the basics that...

MICHELLE PORTER: Basics

KAYTE YOUNG: Other cookbooks might assume you already know how to make gravy so they might not put a recipe in there or mashed potatoes, but you're saying this has all of those basics.

MICHELLE PORTER: Yeah, it has your basics.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: When I heard about this cookbook, that she got it in the mail, as a wedding gift, from her congressman, I wanted to talk to her. My friend Julia put us in touch.

[INTEVIEWING] And so when you got this cookbook did you already know how to cook?

MICHELLE PORTER: Not a lot, I used it a lot when I got it, when I first got it, yeah. No I didn't know. My mom cooked all the time but we had to the do the dishes. But she didn't really. We lived on the farm, and she was out for pigs, and she was out on the tractor. And so when she came in she cooked it, we had to do the dishes. So she didn't really take the time to teach us a lot about cooking. We did the dishes.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: So you weren't invited in to help out?

MICHELLE PORTER: Not... no. Peeled potatoes but not really on the cooking part yeah.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah. So it's a book that you ended up using a lot?

MICHELLE PORTER: Oh I did yes, I did. I used it a lot.

KAYTE YOUNG: What did you think when you first got it in the mail?

MICHELLE PORTER: I don't really remember (laughs)

KAYTE YOUNG: Like were you surprised? Did you think it was a strange thing for your congressman to send you?

MICHELLE PORTER: Yes I'm sure I did think that cause you know I never dreamed about him sending me a free cookbook. I thought that was pretty cool.

KAYTE YOUNG: And you think they just send it out to every married couple?

MICHELLE PORTER: I don't know. One of my friends that's never been married, that's 5 years older than me, she said she got one. But now I asked on Facebook the other day if anyone else had got one, and nobody else answered me. So I don't know how they pick who got them, I really don't.

KAYTE YOUNG: Well what are some of the recipes that you've tried?

MICHELLE PORTER: Probably like the mashed potatoes and just how to do gravy and a lot of your basic stuff. I used it a lot just to know how long to cook meat, there's tables in there to know how long to cook meat to know when it's done. So I used it a lot for that. You can see it's getting pretty ratty. But yeah I used it a lot when I got married. See, here's a biscuits recipe. So just a lot of the basic stuff.

KAYTE YOUNG: Now are you the kinda person who will make notes in your cookbooks and your recipes and stuff about like, oh you know...

MICHELLE PORTER: I will, but you know I didn't in this, so I guess I didn't tweak it any. I probably wasn't as comfortable tweaking then as I am now.

KAYTE YOUNG: So this was kinda something you relied on when you were longer, and as you got more comfortable and maybe had some other cookbooks.

MICHELLE PORTER: Yeah, yeah. And I didn't use it so much. But I did when I first got it, I used it a lot.

KAYTE YOUNG: So yeah I see it's got, it doesn't just have recipes, it starts with a whole section on nutrition.

MICHELLE PORTER: Yes.

KAYTE YOUNG: So there's a guide to good nutrition, and then [Reading from the book] Serving by Serving, Foods Provide for Daily Needs and then it's got a whole breakdown of different foods you could eat like milk and then how much protein, how much calcium, how much of these different vitamins, that's interesting.

MICHELLE PORTER: Yeah it is.

KAYTE YOUNG: Then some stuff about servings. And then [Reading from the book] Shopping, Smart Buying, okay.

MICHELLE PORTER: It's really pretty interesting.

(Sounds of pages flipping)

KAYTE YOUNG: Different types of poultry, vegetables, and then a whole thing about storing food. This is great.

MICHELLE PORTER: Yeah and that was helpful too on the storing food.

KAYTE YOUNG: So it just gives you some ideas for what needs to be refrigerated, what can be held at room temperature, [Reading from the book] store in a cool room away from bright light, that's your onions, your potatoes, your rutabaga and squash and sweet potatoes, okay (chuckles). Some substitutions, a whole thing about...

MICHELLE PORTER: Yeah that's very helpful when you don't carry a lot of stuff.

KAYTE YOUNG: So in place of double acting baking powder, you could use two teaspoons of quick acting baking powder plus a quarter teaspoon of baking soda, plus sour milk or buttermilk, okay (chuckles).

MICHELLE PORTER: I probably used that one where you can add vinegar to the milk and make it sour for persimmon pudding. I probably used that as much as anything.

KAYTE YOUNG: So for buttermilk you can add lemon juice or vinegar. Okay.

MICHELLE PORTER: Yeah, I've used that a lot.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay so then there's a whole thing about just kind of meal planning it looks like some different ideas for main dishes. Okay now we're getting into the recipes, okay.

(Music)

So did you say there's a persimmon pudding in here?

MICHELLE PORTER: I don't know if there is or not... I don't think there is, but I always looked in there to find out when I made my persimmon pudding.

KAYTE YOUNG: Oh! And there's a whole section at the end, ways to use leftovers, that's often. And then some cooking terms, bake, barbeque, bast, marinade, that's great.

MICHELLE PORTER: It's just kind of pretty neat overall.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Our friend Julia got in touch with Lee Hamilton's office to ask about Michelle's wedding gift from the 70's, and surprisingly they sent Julia a cookbook. I showed it to Michelle.

MICHELLE PORTER: Oh! And that's not anything like what I had. No, nothing at all.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: This is one called Nancy Hamilton's Indiana Family Cookbook. And so hers, it's just different recipes and then she has a little note at the end of all of them, like baked spaghetti, [Reading] "Lea's mother made this". Is her little note at the end. Yeah this is just like little almost recipe cards, and they're really short. [Reading] Dump cake - chocolate lover's dream.

MICHELLE PORTER: Oh I love dump cakes.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah. What do you consider to be a dump cake?

MICHELLE PORTER: When you just dump it in there. Well I started out seeing Paula Dean's, and she always started out with a can of crushed pineapple, and then your pie filling, and then your dry cake mix, and then a stick and a half of butter on the top.

KAYTE YOUNG: Huh, the pineapples on the bottom, and then you flip it over?

MICHELLE PORTER: No.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay, interesting. Well this one includes a box of German chocolate cake mix, so that cuts some corners there, then it's got some...

MICHELLE PORTER: See your dry cake mix makes your crumble for the top when you can melt your butter, and when you melt your butter and spread it over your dry cake mix that makes like a crumble topping for whatever you put under it. I do a caramel apple one too that's good. Take two cans of apple pie filling, drizzle caramel on it, then put a yellow cake mix and melted butter, then if you want to, pecans on it is pretty good too. And that's real easy.

KAYTE YOUNG: Oh okay. So you're not really mixing up the cake mix...?

MICHELLE PORTER: No, you don't mix it up.

KAYTE YOUNG: You just put some butter, mix it with some butter, or put butter on top of it.

MICHELLE PORTER: Just melt butter and drizzle it over the top, yeah. Paula Dean's the first one I ever heard of doing it. They're really good, they're real easy. You just dump it in there. That's why it's called a dump cake.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah.

MICHELLE PORTER: Yeah.

KAYTE YOUNG: So you just dump it in the pan, like you're not...

MICHELLE PORTER: Yeah in your 9.5 x 11, yeah.

KAYTE YOUNG: So you don't even have to use a bowl, don't have to dirty up a bowl.

MICHELLE PORTER: No, no.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay so this, the Family Fare: A Guide to Good Nutrition that you received when you got married, and now when was this?

MICHELLE PORTER: It's 1971.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay, this comes from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and it's a home and garden bulletin #1, it was revised in May of 1970 and it's from Washington D.C.

MICHELLE PORTER: Yes.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay so this came to you maybe through Lee Hamilton, but it's from D.C.

MICHELLE PORTER: Yes.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay, well that makes a little more sense of why when Julia got in touch they mentioned this, or they sent her this because they probably thought it was the Hamilton Cookbook that she was talking about. So can you think of any dishes in here that you made more than once, or that you kind of was a go-to for you? You said mashed potatoes.

MICHELLE PORTER: Well the macaroni and cheese, I'll have to admit I tried the cherry pie after we got married and burned it. That wasn't too good of a deal. It's been so long since I used it, I don't really remember. See there's a boiling guide for French vegetables so you'll know when they're done. French toast, my mom never made French toast, so I did learn how to make French toast out of this. Yeah see there's a roasting guide in here. So it tells you how long to roast stuff and it may be on the page before too. And that way you know how long to cook meat then it's done.

KAYTE YOUNG: So even if you don't have a thermometer, to find out.

MICHELLE PORTER: Right my mom never had a thermometer to roast meat, she just... yeah.

KAYTE YOUNG: So do you have kids?

MICHELLE PORTER: I have a daughter.

KAYTE YOUNG: And does she like to cook?

MICHELLE PORTER: She does, and she's a very good cook. Yeah.

KAYTE YOUNG: Have you shown her this cookbook?

MICHELLE PORTER: I actually gave that to her and she used it for a while and she gave it back after she... she's more internet, you know. She'll look stuff up on the internet. Yeah.

KAYTE YOUNG: But so she gave it back to you? Do you think she used it at all for any?

MICHELLE PORTER: Yeah I think she used it some.

KAYTE YOUNG: And are there any recipes that you would maybe pass down to her, or even just instructions that you got from this?

MICHELLE PORTER: Probably have already done that. Now when I make gravy, my mother-in-law taught me how to make gravy, but my daughter Natasha, she follows a recipe to make gravy. And she makes good gravy, but I just dump it in there.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay so tell me how you make gravy?

MICHELLE PORTER: I think one of the main things is do you use a fork or a whisk? You can't use a spoon.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay.

MICHELLE PORTER: And so just however much butter or I always like bacon grease. You have it in the skillet, I sprinkle flour in it, I just kind of eyeball it. And then salt and pepper it and then stir it until it's got all of your butter or your bacon grease absorbed, and then I just pour milk in it and keep stirring until it gets thick.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay and do you have to pour it slowly or...?

MICHELLE PORTER: No I just dump it in there.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay.

MICHELLE PORTER: (laughs)

KAYTE YOUNG: And then you're whisking it with your fork or your whisk until it thickens up.

MICHELLE PORTER: Yup, now my mom always browned it. She always waited until the flour got brown, but I don't do that, I just stir it up.

KAYTE YOUNG: And is that just a preference if you like that nutty brown flavor or not?

MICHELLE PORTER: I think maybe I just don't want to wait as long. (laughs).

KAYTE YOUNG: Well I just want to thank you so much Michelle.

MICHELLE PORTER: Well thank you for having me.

KAYTE YOUNG: That was Michelle Porter talking about a cookbook she received as a wedding gift in 1971 from then Indiana Congressman Lee Hamilton. From my limited research since this conversation, it seems that booklet was frequently distributed from the offices of U.S. senators and representatives, not just Lee Hamilton. From the 1950's through at least the 1970's.

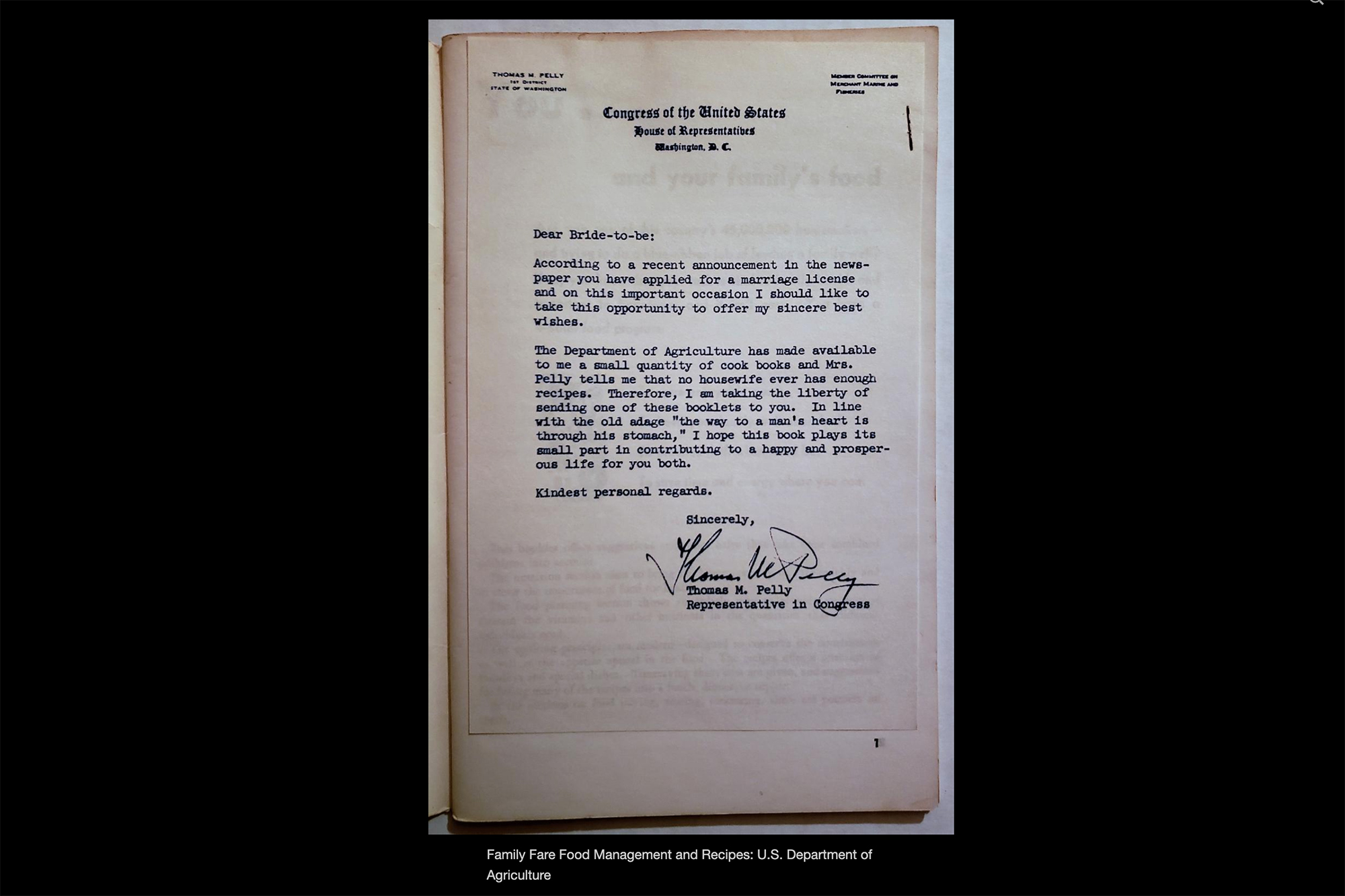

In an eBay search I came across a letter enclosed in one of the copies, from a congressman in the state of Washington saying he knew the recipient was a bride to be based on a newspaper announcement about a marriage license application. He went on to say that he had a limited number of these booklets to give away from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. So perhaps not all married women received them, just a select few. You can see an image of that letter on our website, Earth Eats dot org.

My Mom's basic cookbook was a Betty Crocker one with a red and white hard cover and it was a three-ring binder type. I can remember studying that cookie section very carefully as a child, and I have a version of that one that I still occasionally reference. The cookbook I started out with as an adult was the Moosewood cookbook by Molly Katzen, perfect for the 20-something vegetarian activist. I made my first loaf of bread from that book, homemade pasta, Hungarian mushroom soup, hummus, it was a great start. Now my go to basic cookbook is Mark Bittman's How to Cook Everything. It usually lives up to its name.

I'd love to hear from you, what's your reference cookbook? Joy of Cooking? It is a google search? Epicurious? Also, how did you learn to cook? From whom did you learn to cook? Are you still learning to cook? Drop me an email, EarthEats@gmail.com, or send us a message through Facebook, Instagram or Twitter @EarthEats.

After a short break we'll hear from a guy named Rocky who learned how not to cook from his mom. Stay with us.

(Music)

Thanksgiving is approaching. This year it's going to be different for many of us who celebrate. If you're used to traveling to see friends and family or hosting a big meal at your home, it might feel strange to scale back this year, to stay home. Maybe you're even spending the day entirely alone.

Well in honor of the weirdness that is 2020, we have a story from our friend David Gann in Saitama Japan. You might remember him from his office cooking session on a previous episode, or if you listen to the radio locally you might have heard an Earth Eats promotion with his voice. David is speaking with his friend Rocky, another expat living in Japan, about an annual Thanksgiving dinner he puts together. This was recorded in 2019 when it was safe to gather in small spaces, cooking and talking together without face masks. Here's David Gann with his audio postcard.

DAVID GANN: This is David Gann the office cooker you heard in a previous episode. I am today at the home of Rocky Burton in [INAUDIBLE] City Saitama. So we've been doing this about once a year now, I was over here one year ago for the last dinner that Rocky prepared. And I'm gonna ask you a few questions about your history in cooking. Yeah so first of all how long have you been in Japan?

ROCKY BURTON: It's been about 7 1/2, going on 8 years now.

DAVID GANN: And how did you first get interested in cooking? Were you interested in cooking back in the states?

ROCKY BURTON: Oh absolutely. I've been cooking for about as long as I can remember. The story I always like to tell, and my mother's gonna kill me for this, but I always like to say that my mother was a terrible cook growing up. Everything that she made was burned. She says she liked it that way, she cooked all of her hamburger black, she liked it burned, all of her chicken black, she said she liked it burned. So eventually I just had to learn to do it for myself.

So I also had a really good home ec teacher in high school - Mrs. Jo Ann Robbins. I took her classes a couple of times, and we practice making a whole lot of pastries and a couple of more healthy meals. That's basically where it all came from.

DAVID GANN: Alright will how many of these Thanksgiving dinners have you had in the past?

ROCKY BURTON: I think this is my third or fourth time around, the first couple of times were a little bit easier I think. They were much smaller affairs at maximum it was like 6 or 7 people. But starting from last year we started to have larger groups, we had like 15 or 20 last year.

DAVID GANN: You've got a really incredible array of dishes prepared for today, and we're gonna look at the list.

ROCKY BURTON: Correction I have a huge list of dishes planned. What is gonna be prepared is a fraction of that.

DAVID GANN: Even if it's a fraction it is amazing Rocky, you just cannot get food like this in Japan very easily. And that brings me to my next question, how do you get all of these materials, and in the beginning what kind of difficulties did you have in procuring these items?

ROCKY BURTON: The beginning was easier; they were much smaller dishes and more simple items. For the bigger items, the turkey, the stuffing, the gravy, you have to go out to Keito area out in Tokyo. That's for most of the wealthy foreign executives live, I suppose you could put it. They've got international markets out there. So that's the only place I can really find any turkey unless I want to a Costco and get an entire pulled bird which I cannot cook in my small setting. But the most difficult item to find is baking items.

DAVID GANN: Baking items? Like what?

ROCKY BURTON: Powdered sugar is impossible to find.

DAVID GANN: Powdered sugar? Wow.

ROCKY BURTON: Powdered sugar. You can find them at the Kaldi store, the small-time international store, but those are only in really small packages of 75 grams or so. But I had to send out for a larger packages, I got this one package here, it looks like 500 grams. So what I did I hopped on amazon ordered like 4 or 5 bags of those, I've been keeping those for as long as I can. Sometimes you have to stretch your ingredients and between you and me keep them a little bit past their expiration date.

DAVID GANN: Well how bit this cranberry sauce you're making over here, this looks like something that might be difficult to find in store.

ROCKY BURTON: You can find cranberry sauce and as a matter of fact that reminds me I have one can left. But the canned cranberry sauce is to me only a garnish. So I've been getting the canned, the jellied stuff. That is traditionally put on a plate in the center of the kitchen table and then picked at. People put it on their plates and then they throw it away. That's how you eat the canned cranberry sauce.

DAVID GANN: What a waste.

ROCKY BURTON: Nah that's what it's used for. It's just for coloring on your plate. But the real cranberry sauce you have to make it at home, you have to cook it yourself. Now you cannot find cranberries in Japan anywhere except for at Costco and even then there's a small window of time of like maybe 2 maybe 3 weeks when it's available seasonally. And so I will occasionally swing by the Costco after work on Fridays and see if they've got any in stock. Around about end of October beginning of November or so.

(Music)

DAVID GANN: I'm looking at the list of the various things including eggnog got on here, I'll just go down the list and please just rap a little bit about some of the various things you've got going.

ROCKY BURTON: And I can tell you what I have made, what I am gonna make, what I'm abandoning.

DAVID GANN: Okay. First of all we have deviled eggs.

ROCKY BURTON: It's in the process, I'm making those. I need to get the eggs in the pots within the next couple of minutes if we're gonna have any.

DAVID GANN: Okay. Cheeseball, flavor to be announced. What is going to be the flavor this time?

ROCKY BURTON: That is going to be a chocolate chip cheese ball.

DAVID GANN: Wow.

ROCKY BURTON: Chocolate chips is another thing you can't really find in supermarkets regularly, so what I do is I go out and get some chocolate bars for really cheap, and just chop them up or hammer them, do what I can with them.

DAVID GANN: Pumpkin hummus, now this does sound interesting.

ROCKY BURTON: Pumpkin hummus is actually pretty easy you can find pureed pumpkin sauce at the Kaldi, that supermarket that I told you about.

DAVID GANN: Garlic whipped mashed potatoes and gravy; man that sounds great.

ROCKY BURTON: Those are done. The mashed potatoes are done, they're on the table now. Gravy will be forthcoming after just a couple of minutes, that's seems like a, it's a lower tier item, it's easier to get around to. That takes like... shoot, 10 minutes.

DAVID GANN: Gravy is not really a very common thing in Japan is it?

ROCKY BURTON: Well I mean not the brown gravy, not the turkey gravy that we're most familiar with. But you can finding ingredients at a various number of places. I went out to the international market in Hiro where I got my turkey from and I got a couple of packages of the simple short stuff, but I decided this here this go for a large cannister. I got a giant cannister of about 240 grams of brown gravy mix and that's gonna be the easiest way to get it all together. I mean I'd love to make my gravy from scratch using just drippings from a roasted turkey breast or a whole bird if I could, but let's be honest I got enough work.

DAVID GANN: It looks like it. This next one is a traditional dish that everyone in America loves, macaroni and cheese. I was a little surprised to see it on here because it's such a simple and basic one, but I imagine you do something special with it, don't you?

ROCKY BURTON: This one's gonna be baked, be a baked macaroni and cheese if the oven will be free in time. I have easily five or ten baked items that are on my list to get to before I get to the mac and cheese but if I can free up the space, just bake it up probably with some breadcrumbs or something like that. Yeah that'll make it a little bit special.

DAVID GANN: Well we're moving on to the entrees now. And I see you've got pumpkin and mushroom risotto, mmm!

ROCKY BURTON: That's what I'm working on right now, I'm chopping up the pumpkin and tossing in a little bit of sage. This is something that I used to make when I took a short time as a vegan diet. So this one can be made vegan. Today we don't have any vegan guests so that saves me a little bit of effort, so I just toss in some chicken stock.

DAVID GANN: Moving onto dessert, you're making cookies. What kind of cookies are you making?

ROCKY BURTON: I've got some chocolate chip cookie dough that's been in the fridge overnight so all of those flavors should be married by now. And with whatever time we have left with the oven, because it's only a small single rack oven, I'll make some gingerbread and hopefully some peanut butter.

DAVID GANN: Finally on the list that you put on your website; you've got boozy brownies.

ROCKY BURTON: Boozy brownies, I love me some boozy brownies.

DAVID GANN: What kind of booze are you putting in those brownies?

ROCKY BURDEN: First you make the brownies based on the mix or from scratch and then you just pour on about a quarter cup of bourbon. That should steam and dry up after just a moment it'll be absorbed into the brownie itself, and then I'll cover it up with a little bit of rum and I think cream cheese frosting.

DAVID GANN: Wow, I can't wait.

(Music)

ATTENDEE: I'm more about the drink today, I'm all about the apple cider that Rocky made, it's spiked with some rum. And the eggnog which I think he probably prepared two days before cause last year when he made this, there was a real strong ethanol flavor. But today it's very... (laughs) it's very smooth. So I've been imbibing in the drink more than I have the food. My kudos to Rocky for making these wonderful drinks today. I don't think he's paying attention.

This is just a reminder of what you have that are non-material goods. And for me friendship is much more important.

SECOND ATTENDEE: Yeah to me Rocky creates a space where you can enjoy something festive which in Japan is really unusual. For kind of us expats out here that maybe don't have many opportunities to interact with family, it really means a lot. So I think we should all say cheers and thanks to Rocky and Rynn.

(Everyone giving cheers)

[In the background]: Cheers to Rocky!

SECOND ATTENDEE: Cheers! And if you have friends who cook you should look after them. (chuckles)

THIRD ATTENDEE: (Speaks Japanese)

FOURTH ATTENDEE: The theater of it has definitely got to be the turkey. No, no, no. Yeah. I think everything's gone down really well. As we can see here where's there's no food left. Well, there's a lot of food of left but, but it's all gone down very well. The risotto was very good, and the guacamole chicken breast was very good. And the bread was very very very good. Yeah. But yeah overall fantastic and again thanks to Rocky and Rynn for putting this together. Yeah.

(Scattered applause)

KAYTE YOUNG: I think I heard cranberry sauce, macaroni and cheese, something with pumpkin in it, so yeah. A nod to a traditional Thanksgiving meal. Thanks so much to David Gann for that audio postcard from Saitama prefecture in Japan.

(Music)

The coronavirus pandemic has wreaked havoc on the meat industry with some slaughterhouses and processing plants temporarily closing down earlier this year. Some midwestern states are using federal covid stimulus money to help small meat processors increase capacity. Harvest Public Media's Jonathon Ahl reports those plants are off to a slow start.

JONATHAN AHL: Larkin Busbye is the L in DL farms. She and her husband grow vegetables and raise beef, pork and chicken on their 168-acre organic farm 90 miles southwest of Saint Louis. Busbye says after the coronavirus spread to the area she got bad news from her meat processors.

LARKIN BUSBYE: We have been told that the earliest processing date for us is spring of 2022.

JONATHAN AHL: Busbye said she had to scramble to find a patchwork of processors who were willing to do the minimum necessary for her farm to stay afloat. This is a common story in the midwest for small processors, the ones that employ 50 or fewer people. Even after the plants reopened the backlog on small operations was still there. States like Missouri and Oklahoma are trying to help. A combination of state and federal efforts have led to millions of dollars being granted to very small meat processors helping them add machines, space, and people. Jennifer Lutes is a community engagement specialist with the University of Missouri extension. She says small processors are excited about the opportunity.

JENNIFER LUTES: They are all hoping to experience capacity and that is their goal and so we kind of have to get this equipment in and see how much things change.

JONATHAN AHL: But that process is slow, the grant programs are reimbursements, so the processors have to front the money for expansion. That means very small businesses with little capital are taking out loans and applying for grants. Scott Long is one of the processors who took the federal money. He owns Cabool Kountry Meats a 10-employee operation in south central Missouri. He says he's ready to add capacity but can't find anyone to take the four jobs the new equipment created.

SCOTT LONG: But we've had some that's quit too. It wasn't their cup of tea. And slaughtering or processing beef is not something for everybody as you can imagine. It takes a special type of individual to do that.

JONATHAN AHL: Long also says what he calls generous unemployment benefits discourages people from taking the jobs that start at $10 an hour but go as high as $16. Advocates for rural areas and small meat processing businesses say pay, training and education are the biggest hurdles to filling these jobs. Megan Filbert works for Practical Farmers of Iowa, an advocacy group, and also raises sheep on her farm. She says the real hang up in the labor market is the image of butchers as a profession.

MEGAN FILBERT: Universities and community colleges should offer artisanal butchery courses, which we're seeing some of that, but open that up to not just students, like college age students, but the general public.

JONATHAN AHL: Filbert says better local butchers will mean better local meat which will lead to a more thriving small processing industry. But she also says that will take time. Filbert says the effort would be more successful if small meat processors had a few years to increase capacity. The government is pushing for the changes in a few months because of covid concerns. All of this effort to improve capacity for small processors probably won't have much effect on meat prices and supply. That Pat Westhoff is an agricultural economist with the University of Missouri, he says even with expanded capacities, small processors well, still small.

PAT WESTHOFF: There's only so much they can do right now, so until you have a lot more of them, which doesn't seem to be the occurrence right now, there's not much that's gonna change in the near term. We're still relying on the big packing plants to get things done.

JONATHAN AHL: While that was the impetus for some of the grant programs it may not be the real goal or outcome. Jennifer Lutes with Missouri extension says the covid fueled high prices and meat shortage got people to think differently about meat.

JENNIFER LUTES: But also it has encouraged consumers to go out and seek local sources, that they may or may not have been aware of previously.

JONATHAN AHL: And Lutes says if covid and the grant programs create a more vibrant meat processing industry that will be good for rural communities, farmers, and the food supply chain as a whole. Jonathan Ahl, Harvest Public Media.

KAYTE YOUNG: Find more at Harvest Public Media dot org.

(Music)

With the winter holidays approaching some of us have pie on the mind. This summer I shared my recipe for galettes, they're a rustic free form pie where you skip the pie pan and simply fold your pie pastry around the fruit filling leaving an open middle. I appreciate their simplicity and the way they maximize crunchy pie crust edges and avoid the dreaded soggy bottom of juicy fruit pies. It's so easy. Here are the steps.

Make the pie dough in the morning, and we have a recipe and instructions for that on Earth Eats dot org. Wrap it in plastic and stick it in the fridge to chill for several hours. Mix the berries with sugar and maybe some corn starch. You can mash them up, slice them or keep them whole. Preheat the oven to 450 degrees.

Then roll out the chilled dough into a rough circle, transfer it to a baking sheet, pile the berries and sugar mixture in the middle and fold the edges of the pastry over the circle of food, leaving at least half of it exposed. Then brush the pastry with milk or cream, sprinkle sugar over it and bake it in a preheated 450-degree oven for 15 minutes. Reduce the heat to 375 and bake another 15 or 20 minutes or until the crust is a deep golden brown.

Allow to cool for 15 minutes or so before serving with a scoop of vanilla ice cream or whipped cream. Make two, so you can share one with someone who could really use the comfort of pie right now.

These instructions are for berries, for apple or for pear just toss the fresh cut fruit with sugar and cinnamon. Find details at Earth Eats dot org.

(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

That's it for our show this week, thanks for listening. Take care of yourselves, take care of each other.

RENEE REED: The Earth Eats team includes Eobon Binder, Mark Chilla, Abraham Hill, Josephine McRobbie, the IU Food Institute, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week to Freddie Bitsoie, Michelle Porter, David Gann, Rocky Burton, and everyone at Rocky and Rynn's dinner.

RENEE REED: Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from the artist at Universal Productions Music. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey.