(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington Indiana, I'm Kayte Young and this is Earth Eats.

ERIC SCHEDLER: One of the things that you'll notice about working with spelt is that it comes together immediately, much more quickly than wheat does.

KAYTE YOUNG: Our guest today is Eric Schedler of Muddy Fork Bakery, and he's teaching us how to make pita bread using stone ground spelt flour. And to fill that pita pocket he'll also share his recipe for falafel. Christina Stella of Harvest Public Media explains why corn needs to sleep. Josephine McRobbie has a conversation with the official chef for a state governor and we talk with professor Andrea Wiley about the complications surrounding gluten. All of that just ahead in the next hour here on Earth Eats, stay with us.

(music)

RENEE REED: Earth Eats is produced from the campus of Indiana University in Bloomington Indiana. We wish to acknowledge and honor the indigenous communities native to this region and recognize that Indiana University Bloomington is built on indigenous homelands and resources. We recognize the Miami, Delaware, Potawatomi, and Shawnee people as past, present, and future caretakers of this land.

KAYTE YOUNG: When the governor and first lady of North Carolina had an opening for a chef at the state's executive mansion, they wanted more than the promise of a great meal. In Ryan McGuire, they found an advocate for farm-to-table eating, improved child nutrition, and the promise of food as a connector. Inauguration week is a good time to give a second listen to this conversation with producer Josephine McRobbie and a governor's chef, Ryan McGuire.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: [Narrating] North Carolina is ranked one of the most food insecure states in the nation, which children and seniors even more vulnerable to malnutrition and scarcity of resources. The State's Governor - Roy Cooper and First Lady Kristen Cooper have been involved with organizations like No Child Hungry since the beginning of Cooper's administration, and they have a unique ally in the chef at state's executive mansion.

I'm standing with Chef Ryan McGuire at Raleigh City Farm, where the chef often puts on community centered events. Recently he was teaching cooking and gardening to the local Salvation Army after school program,

RYAN MCGUIRE: We did some knife skills, and safety practices, and we had some produce that was given from the farm here that we utilized in the cooking classes.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: At the executive mansion Chef McGuire manages a staff who do everything from tending a garden, to working front-of-house for events, to running the kitchen.

RYAN MCGUIRE: I love exploring different types of cuisines. So, I often try to fit some... you know, different flavors in there. And the governor’s been great. He's very open minded, so he has allowed me pretty much free reign on what I like to cook, which is fantastic. I like that freedom.

[Upbeat background music]

We're the people's house as the governor calls it. So, we have events that happen there with nonprofits and other organizations that come in.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Chef McGuire also represents his role around the region. Last summer he visited the local food bank with the first lady as part of the Stop Summer Hunger Initiative, where he did a recipe demonstration that used only food bank ingredients to make an Asian-inspired meatball dish. In 2019 he was a participant in Durham Bowls, where a local chefs team up with school cafeteria workers to develop fresh recipes for the public school system.

Chef McGuire grew up in the neighborhood-centric Buffalo New York, the grandson of a Sicilian immigrant.

RYAN MCGUIRE: He'd go to one part of town for your Italian sausage, he'd go to one part of town for your polar sausage, or your kabasa, or your pierogis. You have these little pockets of people that live in these different areas.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: His most memorable food experiences were the ones that were challenging on the palette, like eating pasta with sardines as part of the St. Joseph’s catholic feast day. But later he learned in his child nutrition work that it can take a person a dozen times eating a food to develop a taste for it, and that it can be worth the struggle.

RYAN MCGUIRE: It always brings me back to Grandma's house or something, if I have a taste of that sauce that she would make. So, it's something that I feel is extremely important to continue because it's the only real thing I can grasp onto and try to pass on to my family. So we had a really nice St Joseph's day last year with friends and family. And I hope to do that, continue that tradition.

I got into the culinary world sort of by mistake, just because it's usually one of the first jobs you can get as a teenager. And I started washing dishes at a Kentucky Fried Chicken.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Later Chef McGuire ended up getting his first real restaurant gig when he was called back accident for a job interview.

RYAN MCGUIRE: And the guy thought I was someone else. So they called me in, and since I was there they kinda put me to work, and I started working at this really neat bistro. I started learning more about cooking from a couple of the chefs that were there.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: After completing culinary school and working in restaurants in Manhattan, he took a job as a cook and educator at the Virgin Island Sustainable Farms Institute.

RYAN MCGUIRE: The types of fruits and vegetables that you can grow there was phenomenal. You know, we had pineapples and different types of bananas, and all kinds of really neat fruits of course mango and avocados, and starfruit, carambola. There was soursop. It was pretty cool.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: [Narrating] In North Carolina he worked at Walt's Grocery, an award-winning farm-to-table restaurant owned by Amy Turnquist.

RYAN MCGUIRE: You know she would go down to the Carrboro Farmer's Market and just stuff her car full of vegetables and bring it back to the restaurant. We didn't even really need it I think. She just loved supporting the farmers there. And you know and telling us to try to find a use for it. And so, it was neat to be able to learn some of the local growers and suppliers in the area that way.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: [Narrating] This interest in food systems lead him to a position at Chartwells, a K12 nutrition strategy company working with the local schools.

RYAN MCGUIRE: It's such a beast of a system, trying to figure out how to make food delicious, and healthy, and affordable for kids.

When we first got there it was just a couple small steps to improve. I think improve some of the food was... we're doing things like taking the fryers out of the schools. The company that was there before was really not so concerned with what they called "reimbursable meal." They were just selling a la carte items. The district wanted to change that, so they wanted to sell more of a meal, and incentivize us by doing that as opposed to doing a la carte. So that students would have a full meal, not just a chicken wings or French fries.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Nowadays Chef McGuire is most interested in the concept of Gastrodiplomacy. It's practiced by groups such as the Bronx's Ghetto Gastro, who used the burrow's food culture to foster dialogue around social or economic or geographic borders. Gastrodiplomacy can be boiled down to that old saying - "the easiest way to someone's heart is through their stomach."

RYAN MCGUIRE: It can be pretty simple though. It can be as much as having a group of people coming to the executive mansion for example, that are there for a meeting, and maybe they are fed a nice meal. And it kind of opens their mind a little bit, and it might open them up a little bit more to a better conversation. And I'm all for that.

KAYTE YOUNG: That was Earth Eats producer Josephine McRobbie speaking with chef Ryan McGuire. Find more at Earth Eats dot org.

(Music)

Many Great Plains farmers saw abnormally warm and dry weather last season. That may make you think of withered crops and cracked soils, but those conditions can pose another risk for plants - hotter nighttime temperatures. And as Harvest Public Media's Christina Stella reports, that's expected to become an ongoing problem for crops that are just trying to get some sleep.

CHRISTINA STELLA: Some farmers say that if you listen to their cornfields closely enough you might hear more than ears of corn rustling in the wind. You could catch the sound of it growing. There are recordings, like this one taken by agronomists at the University of Nebraska Lincoln.

(Sound of corn growing - rustling and peeling)

Farmers pray every year for conditions that will make their crops sing like that, enough moisture, proper sun, no bad weather. In 2020 on top of the year's many problems a stubborn enemy emerged for farmers across the great plains, drought.

Dry conditions can hurt crops yield by interrupting photosynthesis. Air, plus water, plus sunlight equals corn. But drought conditions can also go hand in hand with warmer weather, too little or too much heat at the wrong time can doom a farmer's field. Brian Fuchs a climatologist at the U.S. National Drought Center says both can arise in a heartbeat.

BRIAN FUCHS: For the most part the timing of that warmth is really key to how not only producers themselves deal with it but how the plants and the crops that they're trying to grow deal with it.

CHRISTINA STELLA: Corn is especially picky about nighttime temperature early in its life. If just a few evenings at the start of the growing season are hotter than 50 degrees that can trigger a cascade of problems, including the plant losing essential carbon and water. Dr. Walid Sadok an agronomist at the University of Minnesota says the effect is similar to getting a bad night's sleep, which can stunt the plant's growth.

- WALID SADOK: When you have that freezing nighttime temperature the plant does not recover well in the following day. It's kind of dizzy.

CHRISTINA STELLA: Climate change is expected to make drought, heat waves, and warm nighttime temperatures more common in coming decades. And while they don't always go hand in hand a warmer world could make drought worse in the future.

- WALID SADOK: There's no doubt the frequency of those extreme events is on the rise. We need to make crops more resilient to stresses like drought, high temperature, high nighttime temperature fast enough to fulfill the need of a growing population.

CHRISTINA STELLA: The search for more resilient plants begins in virtual reality with crop modeling. Sadok uses computer models to test how changing a plant’s genes would impact it's growth. It's sort of similar to playing a really complicated video game, it's all about trial and error. Plants like corn have about 12,000 more genes than humans and changing them to make the crop tougher against say high heat could make it weaker to something else. Like drought.

- WALID SADOK: What we are discovering is that you can improve a variety to be more tolerant in one environment, but it could be really a loser in another environment.

CHRISTINA STELLA: While there's still a lot of work ahead to create enough varieties to use globally, Sadok says scientists are making good progress. Yet stronger plants alone will not save farmers. Tala Awada a plant ecophysiologist at the University of Nebraska Lincoln says they need a bigger toolkit, including better resource management.

TALA AWADA: You can go with using sensing technologies to drive management practices such as when you put your nutrients, when you water, and so all of it is technology driven and sensing driven.

CHRISTINA STELLA: The technology is there, whether it's accessible to farmers is another question. She says that will drive whether more people will invest in equipment that reduces their risk.

TALA AWADA: All of these technologies and advancements and innovation that are driving many of the solutions, but they have to be two things, affordable and manageable.

CHRISTINA STELLA: Farming has always been risky, but to prepare for a changing climate a lot of cis scientists will keep developing tools to help farmers encounter uncertainty, but those will take time to perfect and for some solutions farmers might just have to wait. Christina Stella, Harvest Public Media.

KAYTE YOUNG: Harvest Public Media reports on food and farming in the heartland. Find more from this reporting collective at Harvest Public Media dot org.

(Music)

Next we have a story from 2019 when Producer Alex Chambers still graced the Earth Eats staff.

ALEX CHAMBERS: So Kayte, you eat gluten?

KAYTE YOUNG: Uh, yeah.

ALEX CHAMBERS: And I know this partly because you make incredible pies.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah, Pie.

ALEX CHAMBERS: And also you may remember we taught a bread class together?

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah, you can't make bread without gluten!

ALEX CHAMBERS: No, you can't. Do you know a lot of people who are avoiding gluten?

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes. A lot of people.

ALEX CHAMBERS: It's just crazy to me how many people I know who are avoiding it - my mom, my brother. I was in New York a couple of weeks ago, visiting a couple of childhood friends and both of them are avoiding it. One of them said to me, "You remember how I used to be lactose intolerant?" And I said, "Yeah, I actually do remember that." And he said, "It turns out, I got tests a while back and I'm actually gluten intolerant, not lactose intolerant."

KAYTE YOUNG: Oh, wow. Well it can be hard, when you're a baker and your friends and family don't eat gluten.

Alex: It's a real bummer!

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah.

ALEX CHAMBERS: Although it's probably more of a bummer for the people who can't eat it.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah, and I do wonder what's going on with that...the increase?

ALEX CHAMBERS: Yeah, I know, it's really interesting, I've been wanting to figure it out, too. So I talked with Andrea Wiley, who's been on the show before, and Christa Voirol, who's been collaborating with her to try to answer that question.

KAYTE YOUNG: Great! What'd they find out?

ALEX CHAMBERS: It's complicated.

KAYTE YOUNG: I figured.

ALEX CHAMBERS: So, there's Celiac disease, which is an immune reaction to gluten, affects about 1% of the general population. But you don't have to have celiac to have a problem with wheat. Enough people are feeling better without wheat that sales of gluten-free products almost quadrupled between 2011 and 2015.

So many people are avoiding gluten that some doctors are warning their patients against a gluten-free diet if they don't have celiac disease because sometimes it means replacing whole grains with more highly refined starches like potatoes, and tapioca, and rice.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah, I could see that.

ALEX CHAMBERS: But other people feel like those doctors are discounting their own experiences of feeling better by avoiding wheat. That's what I was trying to understand when I invited Christa and Andrea into the studio.

[INTERVIEWING] So, if you could each just start out by introducing yourselves?

CHRISTA VOIROL: I'll start. My name is Christa Voirol, and I'm a senior at IU and a Cox research scholar, and I've been working with Dr. Wiley now this will be my fourth year, on our gluten project.

ALEX CHAMBERS: Great

ANDREA WILEY: Oh yeah, so I'm Andrea Wiley, I'm professor of anthropology here at IU. I am a biological anthropologist, so I'm interested in human evolution and human biological variation. My particular interests are in the role that diet has played in shaping human evolution and human variation.

ALEX CHAMBERS [VOICE OVER]: Andrea Wiley's been on Earth Eats before, talking about her research on milk. But whereas the main problem with milk is lactose intolerance, it seems to be more complicated with wheat.

ANDREA WILEY: there's a spectrum of wheat intolerances, and there are three kind of major categories. There's celiac disease, which is like an autoimmune disease. So when you consume gluten your immune system essentially starts to attack the cells of your small intestine and eventually it destroys them. So that is one end of the spectrum.

There's wheat allergy as well, which is also immunologically driven, but it is driven, it's mediated by a different part of the immune system, the IGE system, and the mechanism is similar to any kind of food allergy. And that's not particularly common. It's more common among kids, as are most food allergies. And then there's this other category that is called non-celiac gluten sensitivity.

CHRISTA VOIRAL: Yes. Some researchers have also considered adapting the name to non-celiac wheat sensitivity, but you can also kind of run into problems there because wheat is not the only gluten-containing grain. Also popular gluten-containing grains are barley and rye.

ALEX CHAMBERS: So, we've seen that that celiac itself has actually increased, and it's not just due to better diagnosis. There was that study where they took the blood samples...

ANDREA WILEY: The army recruits!

ALEX CHAMBERS: I think yeah? From the army recruits. They were taken in what the 50s? And saw that the rates of celiac in their blood samples was way lower than what we're finding in similar populations now. So celiac is on the rise.

CHRISTA VOIRAL: When you look at celiac on its own and, for example in that study of army recruits, it can seem really alarming. But when you look at it within the context of other autoimmune diseases, other autoimmune diseases are also on the rise at the same or similar rates as celiac's disease.

ANDREA WILEY: Or at least it's part of the package right? So the question becomes why are autoimmune diseases in general on the rise. And there are a number of hypotheses for that.

I would say, thinking about more of the cultural stuff I think it has to be put in the context of interest in low-carb diets, for one thing, that begin kind of in 80s and the 90s, with Atkins at the start where you're really eliminating things like bread from your diet. And some people report great success in removing carbohydrates from their diet, and now that has transformed into the Keto Diet, and then of course there's the Paleo Diet, and all these diets would eschew wheat, rye or grains of most kinds. So there's probably some conflation in people's minds about gluten and carbohydrates. Right? That "Oh well, bread has carbohydrates and oh I've also heard it's got gluten in it." and so collectively those become things that you can eliminate from your diet if you're trying to achieve weight loss for example.

ALEX CHAMBERS [VOICE OVER]: The number of people avoiding gluten has turned out to be a big market opportunity. I mentioned to Andrea and Christa that by 2020, the sales of gluten-free products are projected to be almost 24 billion dollars.

ANDREA WILEY: That seems an incomprehensible number. So clearly-

CHRISTA VOIRAL: Someone's buying them.

ANDREA WILEY: Whether they are self-diagnosed or otherwise diagnosed as gluten sensitive, perhaps there is a larger sense that "Mhm, maybe gluten is something to be avoided." And hence, given a choice between two products, one that doesn't have the gluten-free label and one that does, I choose the gluten-free one, because it carries some kind of health halo. And so it must be, "I didn't know that gluten was bad but if it doesn't have it, then that seems good." It's not an uncommon marketing ploy when it comes to food labeling.

ALEX CHAMBERS: Yeah, I mean that health halo goes beyond food. I get this shampoo that I use, it's sort of an eco-friendly shampoo, and it's gluten-free also, apparently.

ANDREA WILEY: (Laughs) Yeah, so clearly gluten has some cultural currency right now, and some real currency. One of the things the wheat industry says and this is true in my limited experience, is that gluten-free products are more expensive. And so we want to be careful. There are probably lots of people out there consuming gluten-free foods who don't need to be, and so they're essentially wasting their money. Again, that's the wheat industry's line in this. Obviously they have an interest in minimizing this, and eager to see this trend go away.

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: But while the popularity of gluten-free diets suggests it's the latest fad diet, a lot of people are experiencing discomfort, and researchers are trying to figure out why. One of those questions is whether the problem is the gluten itself, or something else.

ANDREA WILEY: So there are other components of wheat that people seem to be sensitive to as well. There are enzymes in wheat that seem to trigger intolerant symptoms, there are also...

CHRISTA VOIRAL: Carbohydrates as well.

ANDREA WILEY: Yeah, there's this whole category of, what would you call them, food constituents called FODMAPS which you may or may not be familiar with, which are sugar molecules of varying sizes and complexity.

ALEX CHAMBERS [VOICEOVER]: FODMAP, by the way, stands for fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols, in case you were wondering. Okay, back to Andrea.

ANDREA WILEY: And wheat has a number of those as well. And FODMAPS have been shown to have some of the same symptomatology as gluten intolerance, and there are a number of studies where if you take people who say they're gluten intolerant and reduce their FODMAP consumption they actually get better, even when you reintroduce gluten, so there is some confusion about whether gluten is-it surely is, but is it the only constituent of wheat that is bothersome.

ALEX CHAMBERS: And another reason it's hard to figure out whether it's gluten, or FODMAPs, or something else, is that the only way to figure out whether someone has non-celiac gluten sensitivity is by how they report their symptoms.

ANDREA WILEY: Right now there is no biomarker either for nonceliac gluten sensitivity.

So, that is one of the key problems in the field right now, is there's no established marker for it. It's really all done by well, if you take gluten out of someone's diet, do they report feeling better. And then it becomes very important to run a double blind placebo study, so that people aren't simply reporting, "Well, yeah, I removed gluten and I'm feeling great." And those studies that have kind of looked at FODMAPS vs gluten in a blinded way have found in some cases that the FODMAPs are the problem and that when people are eating gluten and not knowing it they're actually doing okay. For some studies. Other studies show the opposite. And so the evidence isn't all converging, at this point, which makes for a very messy science right now.

ALEX CHAMBERS [VOICE OVER]: And it's not just the hard science that's making it complicated.

ANDREA WILEY: A strand of this too is kind of this trust in science and skepticism of science, and I think we're at a particular moment in our history where that is really kind of coming to a head. And I always find it kind of interesting, in a political sense, I have many colleagues who will defend science and its benefits against the current skepticism, but have their own kind of... I think again we are our own experiments. (A person saying) "I have this particular experience, it doesn't match up with the science." And so I, what am I trying to say here, "I privilege my own experience over the science." And that's fair, in some respects, science only tells you about probabilities of things, they don't tell you about experiments of one. And I think gluten is a good example where skepticism and science kind of ride, skepticism of the science, skepticism of this as a real phenomenon, are present with science trying to figure out what this is.

ALEX CHAMBERS [VOICEOVER]: In other words, it's really hard to tease out the cultural aspects of this from the biological ones. Are we thinking we're feeling better because we've been hearing for decades that carbs are bad for us? Is there something about our immune systems that are having more trouble dealing with wheat than we used to? Or is there something different about the wheat itself? There's good evidence for all of these things, even though they seem like they would cancel each other out. What's to be done? Well, one thing I would say is, don't pay too much attention to individual studies. As Andrea pointed out, they're pretty quick to contradict each other. When you can, eat whole grains. There's consensus on that. As for wheat, and gluten, and FODMAPs, do what works for you. The research is probably going to converge eventually. The scientists and the anthropologists are on it. For Earth Eats, I'm Alex Chambers.

(Music)

KAYTE YOUNG: That story was produced by Alex Chambers in 2019. Alex's latest project, The Age of Humans can be found wherever you get your podcasts. Find a link at Earth Eats dot org.

(Music)

I'm Kayte Young, this is Earth Eats. Next we have a baking session with Eric Schedler of Muddy Fork Bakery. Muddy Fork is a local artesian bakery with a woodfired brick oven. They make crusty loaves of bread, flakey croissants, and soft pretzels. Eric is a regular guest here on Earth Eats, he's generous with his expertise in the kitchen and this week he'll be teaching us how to make pita bread with spelt flour. He walks us through the steps of making the dough and how to bake the pitas for that signature pocket.

This story is from 2019 when I had the chance to visit with Eric Schedler in their commercial kitchen on their property located on a country road a few miles east of town.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Today we're gonna make some spelt pita. You can make pita with all kinds of flour, you probably think of mostly white flour in a pita, but if you are interested in whole grains pita is a great way to try out using spelt. Spelt can be a little trickier can to work with than wheat. Spelt is a wheat family grain, it's an ancient grain. And it has a little bit of a different dough quality to it that actually lends itself really well to being used in pita, pizza dough, flat breads, because it has a great ability to stretch. It just stretches really easily without ripping so it makes it easy to stretch things out like pita, and pizza dough. It also has a quality in finished bread or flatbread where it's a very soft sort of spongey texture which I think is really great for pita. So we're gonna make whole grain spelt pitas today.

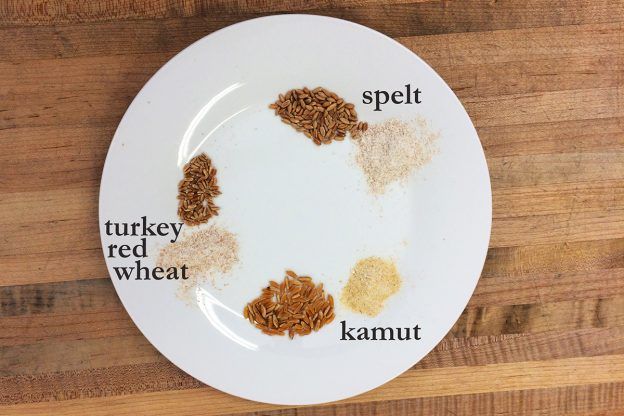

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay we're gonna pause here for a quick tour through a few of the wheat types that Muddy Fork uses in their weekly baking.

ERIC SCHEDLER: So I have three different kinds of wheat here. I have turkey red wheat which is an heirloom wheat from the 19th century that was brought to Kansas by Mennonites immigrating from the Ukraine. And at one time it was the most popular wheat, most widely grown wheat in the U.S. It almost disappeared and is having sort of a revival among bakers. So the turkey red wheat is the wheat that we use in our whole wheat breads, and it looks like a typical hard red wheat. Turkey red is winter wheat, as a hard red wheat it's got sort of small reddish, brownish, looking grains.

And when we compare that with the ancient grains those are quite a bit larger. The spelt is a similar color to the red wheats. It's got that reddish, brownish color. But it's a lot softer than the turkey red wheat so we can take a grain and...

(Snap)

That's the turkey red. It goes crunch. And if you take a grain of spelt.

(Softer snap)

It's a lot easier to chew, even though it's bigger. And that makes it unique because among modern wheats the soft wheats are lower in protein than the hard wheats and they're softer to chew which is why they're called soft wheats. But the spelt is actually a high protein grain but it's got a soft texture to it. It has its own distinct lineage because it's an ancient grain. And as we discussed, it has a different quality to the gluten that makes the dough feel different and behave differently.

Now we get to the kamut which is the biggest grain and it's golden in color. It's also golden all the way through whereas the other, the spelt and the red wheat are only red on the bran. But once you cut them open they're white inside. This is gold all the way through. And it's related to semolina which also has that quality of being golden all the way through. The kamut is also very high in protein and iron too I think, and it's really hard. Super hard.

(Hard loud crunch)

KAYTE YOUNG: Was that your tooth or the grain?

ERIC SCHEDLER: I'm not sure, let me figure out (both chuckle).

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: So now back to the spelt pita dough.

ERIC SCHEDLER: And this is freshly milled spelt off of our stone mill. Which if you like our Muddy Fork flour you can find it at BloomingFoods. If you're into making bread you may have a little tabletop grain mill at home and you can mill your own spelt.

Alright so we're gonna start with water and yeast. This recipe is gonna make six 4oz pitas. And I only bake bread doughs by mix and make bread by weight which is very typical in bakeries. It's not as typical in the U.S. for home cooks to use a scale, but it's easier and more precise than measuring, especially when you get to big quantities, you gotta measure 20, 50 cups of flour would be ridiculous. So we weigh everything. So we're gonna get 315 grams of water.

(Sound of water being poured)

And then we'll put the yeast in the water for just a minute to let it dissolve.

Okay so we want a gram and a half of yeast. There's a simple rule about weight conversions with the dry yeast and that is a quarter teaspoon is about a gram. Our tablespoon is about 10-12 grams. So for a gram and a half we're gonna do a quarter teaspoon, which is one gram, and then a half of that quarter teaspoon.

I'm impatiently whisking the yeast to get it dissolved a little faster.

(Sound of water sloshing as it's whisked)

Yeast is dissolved, now we're gonna add the other two ingredients which is the spelt flour and the salt. We want 375 grams of spelt. So spelt is pretty thirsty flour and you can see there's only a little bit more flour than water in this dough. We can get into baker's math, but the basic idea of how professional bakers describe their recipes is by percentages so that it can be scaled to any particular amounts. So in this recipe if you count flour as 100 parts, then the water is 84 parts to that, so we would say this dough has 84% hydration. Everything is measured against the flour. Flour always counts as 100%.

And the salt, 6 grams of salt which is about a teaspoon and a third. See how close that is. I'm using a teaspoon and the scale at the same time. I think closer to a teaspoon and a quarter. Get yourself a spoon and stir it up.

(Sound of dough being mixed)

If you've made bread dough from wheat flours before then one of the things that you'll notice about working with spelt is that it comes together immediately much more quickly then wheat does. The gluten has a different quality to it where it just becomes cohesive right away. And then it becomes very extensible as it ferments. And when I say extensible I mean the quality of stretching out, flattening out. If you were to take a ball of spelt dough and a ball of wheat dough, the spelt you could watch it spread out before your eyes in the way that the wheat doesn't. I did what I could with my mixing spoon and now I'm sticking my hands in here to incorporate this flour.

KAYTE YOUNG [TO ERIC]: It doesn't look that sticky.

ERIC SCHEDLER: It's wet, but it's not that sticky.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: He's basically pulling a piece of the dough over the top and kind of pushing it in and spinning the bowl around as he does so.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Yeah so I like to knead and mix the dough in the bowl rather than on the table which is sort of a more old-fashioned way to knead your dough because you keep adding more and more flour as you're working it on the table.

Alright that's it, that's our spelt pita dough. We're just gonna set it on the other side of the room and let it sit for a few hours. We'll come back and give it a few folds during that time which helps build strength in the dough. And that looks really the same as my mixing technique where I'm taking a little piece of dough from the edge of the bowl, pushing it down in the middle, spinning the bowl a little bit, pulling another piece. When I talk about folding dough we're just gonna go around the whole circumference once or twice and that's a fold.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: So the dough has been mixed, now it needs to ferment. When we come back we'll divide the dough and get it ready to shape for the pitas.

(Music)

I'm Kayte Young, this is Earth Eats. And we're back with Eric Schedler of Muddy Fork Bakery. We're making pita bread today using Muddy Fork's freshly ground spelt flour.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Here we have pita dough which has been going for two hours, it's very puffy.

KAYTE YOUNG: Bubbly

ERIC SCHEDLER: It has a nice grainy, fermenty smell to it. It's a little sticky looking. I'll put some flour on a table and pull it out with my bowl scraper. Maybe a little heavier on flour then some of the other ones because it's a wetter dough. And we're gonna cut this into 4oz pieces for our pitas. I wanted to just make sure it's just not stuck to the table so I'm gonna slide it around on some flour and let it pick up a little bit of that on the bottom side. And then I'll cut with my bench scraper.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: If you're not familiar with a bench scraper, it's an essential tool for many bakers. It's basically a wide flat blade, a rectangle with a handle running the length of one side of the rectangle and it's not a terribly sharp blade. It's less like a knife and more like a metal spatula. And it's great for cutting dough, scraping your work surface, and moving pieces of dough around on your table or countertop. It's also sometimes called a bench knife. Eric is using it to divide the dough.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Just six little balls there, well six little lumps, now we're gonna make them into balls. And we're gonna make them as tight as we can and the more evenly tight you can make the balls the more likely it is that they'll puff up the way that you want them too. So we're gonna use a little flour, and we're gonna use the same kind of motion that we used before where we pulled the dough from the outside to the middle, but now it's on the tabletop instead of on the bowl.

And when you get to the end there's this tightening motion you can do by pushing the seam against the table and rotating and sort of tugging the dough up and inside. If you did this all day you can do one with each hand. You want to get a little traction with your dough on the table. The sound of the dough sliding on the table.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: This can be difficult to explain without seeing it, but he's basically holding the small piece of dough in his hand and pushing it slightly against the table while rotating the ball. He's tucking the bottom of the dough in and under and creating a nice taut surface across the top of the dough ball.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Running out of flour so I put a little bit more down here.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: It takes some practice to get this part down.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Alright there we've got six nice little round balls of spelt dough to make pitas.

(Music)

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: Normally Eric would bake the pitas in the brick oven in the bakery.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Which is 7.5 feet deep and 5 feet wide and that's a little bit cool right now because we have a weekly heating and baking cycle and the oven just retains heat for the whole week. When we're finished heating it on Friday night it's about 670 and at this point on a Tuesday in the middle of the day it's at 365.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: And that's too cool for our pita baking so we took the dough on a short walk up the hill to the house where Eric and his family live. We'll bake the pitas in Eric's regular home oven. You might hear his youngest daughter Ruth in the background.

ERIC SCHEDLER: So we've got our balls of dough that have been resting for 30-40 minutes, and just taking them up off the wooden board or if you might just have them sitting on your table. And put quite a bit of flour on them because you're gonna roll them thinly so you'll use up that flour quickly. And I start rolling them with the rolling pin and I'm rotating frequently so I try to keep the shape nice and round. Of course if you have ovals, no problem. I'm just used to making the things look round. And we want them to be about 6-8 inches across I think.

KAYTE YOUNG [TO ERIC]: And those don't seem to be springing back that much.

ERIC SCHEDLER: No, and part of that is spelt because the spelt has that extensibility to it, where it will stretch easily. And the rest they have a nice after rounding them. If you try to roll them right away they definitely would.

Okay we've got two pitas ready to go here.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: After rolling out the pitas he's placed them on what's called a pizza peel, it's one of those large wooden paddle shaped tools with a long handle. It makes it a lot easier to slide things like pizza or pita bread into a hot oven.

ERIC SCHEDLER: I've preheated some fire bricks in the oven, and you can use a pizza stone in the same way. I just happen to have fire bricks lying around from having built a brick oven. And I preheated them at about 500, and now I've turned the oven down to 450. It emulates a brick oven because in our wood fired oven the bricks are the heat source, so the air is always a little cooler than the bricks.

KAYTE YOUNG: Oh

(Metal scraping sounds as the pitas are pushed into the oven)

ERIC SCHEDLER: There we go, sliding them on, closing the door.

KAYTE YOUNG: And then on the peel you had a little bit of rice flour, but you could use corn meal, or you recommend...

ERIC SCHEDLER: You can but I really like rice flour on a peel, I think it's more effective than regular flour or corn meal. It also burns at a higher temperature than corn meal and wheat.

KAYTE YOUNG: So you don't get that smokey...

ERIC SCHEDLER: You don't get as much. Depends on how hot your oven is. Our bread oven is about 670 when we start baking bread on Friday nights so.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: Baking pita is a fun thing to do with kids, or really with anyone who hasn't lost their sense of wonder. After a few minutes in the hot oven they begin to puff up as the signature pocket fills with steam. With an oven light and a window, it happens right before your eyes, like a time-lapse video, but it's real time. It's quite magical.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Alright I'm gonna crack open the door. And it looks like they started to inflate, turning into little balloons in there. So we're gonna just make sure the bottoms get a little bit brown. Which they're not yet, and then we'll flip them over.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: This is a small flat bread, so it doesn't take long.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Alright I'm gonna flip these pitas over. I think it's easier with a spatula then using the peel. There we go. I popped them too.

KAYTE YOUNG [TO ERIC]: So now they're deflating.

[VOICEOVER] As always we'll have this recipe available on our website, Earth Eats dot org.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Alright so the first two pitas are done. We're taking them out and I like to cool them on a plate with a towel and so you make a stack of pitas and as you're taking them out and making the stack bigger in between each batch you bring the towel over it to cover it so that they stay moist and warm and soft.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: And that is how you make pita, each batch only takes a few minutes to bake. You can make a whole stack of them for dinner, and the extras keep nicely in a plastic bag for lunch the next day.

Next up we'll share a recipe for what to put inside your pita pockets. Eric will show us how easy it is to make your own falafel from scratch. It's a lot simpler than it sounds. Stay with us.

(Earth Eats production support music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

RENEE REED: Get freshest the food news each week, subscribe to the Earth Eats Digest. It's a weekly note packed with food notes and recipes, right in your inbox. Go to EarthEats.org to sign up.

KAYTE YOUNG: If you have ever made falafel at home you likely started with a box mix. That was before you learned how easy it is to make it from scratch with chickpeas and it doesn't require hours and hours of cooking beans on the stove. You don't even have to break out your pressure cooker. Falafel is a vegetarian dish with origins in the middle east. Israelis and Palestinians have been arguing over who gets to claim falafel as their own but the spicy fried bean nuggets most likely originated in Egypt. They're sometimes made with fava beans, but chickpeas are also common. Eric Schedler of Muddy Fork Bakery shares how he makes falafel with chickpeas that have been soaked overnight.

ERIC SCHEDLER: So we're gonna make some falafel to eat with our spelt pitas. And we're gonna do it all in this food processor, it's a really simple classic recipe. So I need half of an onion and a few cloves of garlic. I'm gonna chop them up in there, and then you use soaked but not cooked chickpeas.

Just gonna chop it up into a few pieces before I put it in the food processor.

You just smash the garlic then you peel it. Throw the garlic in.

KAYTE YOUNG: So how many cloves of garlic did you put in there?

ERIC SCHEDLER: 4. Whenever a recipe says 2-4, I'm always at 4 or 5. (chuckles) Alright and we're gonna put in the parsley and cilantro that we got in the greenhouse. Probably more than a recipe would call for but can never put too many fresh herbs in your cooking.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: When you have a greenhouse on sight like they do out at Muddy Fork, you can have fresh herbs year-round.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Alright we're gonna chop up those herbs, onions and garlic before we add the chickpeas.

(Sound of food processor whirring)

Mm I smell the cilantro. So this is half a pound of chickpeas, half a pound dry and then soaked overnight. Alright, got half the chickpeas in there but my food processor can't hold them all.

(Sound of food processor whirring)

Should look about the texture of bulgar when it's chopped enough. Put this in a bowl and then toss this together with the other half of the chickpeas.

KAYTE YOUNG: Ah that smells incredible.

(Sound of food processor whirring)

ERIC SCHEDLER: Alright so I'm gonna try to mix the two batches together. I'm gonna taste a little bit of it even though it has not cooked beans it, because I soaked the beans in salt water, and I don't know if it has enough salt. I think it needs a little more. I put my other teaspoon of cumin in too. Then after mixing you're supposed to let the falafel mix chill for a while, I think it's supposed to make it easier to form balls that will hold together. Okay.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: After the mixture has had a chance to rest, form it into balls or small discs about an inch or two around.

ERIC SCHEDLER: So whenever you're gonna fry you want to be prepared, you have a place where the finished food is gonna go, in case it's a plate with some paper towel on it. You have your oil with a thermometer in it so that you get it to the right temperature in it, which is usually, for most foods, between 350-375. And a slotted spoon for taking things in and out of the oil and here we go, we're gonna roll a few balls and throw them in. Try to squeeze it together so it holds.

(Sound of oil sizzling as falafels are added)

Temperature dropped a lot. Manage your hot oil as you go, keep adjusting the flame.

KAYTE YOUNG: Those are perfect.

[VOICEOVER] The falafel is done when it's golden brown all around. Remove them with the slotted spoon and place them on a paper towel drain. Each batch only takes a couple of minutes to cook and surprisingly they absorb very little oil. Walking us through the steps was Eric Schedler of Muddy Fork Bakery. Falafel is the ideal filling for spelt pita bread. You can find the recipe for the falafel and the pita at Earth Eats dot org.

(Music)

(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

That's it for our show this week, thanks for joining us. We'll see you next time.

RENEE REED: The Earth Eats team includes Eobon Binder, Spencer Bowman, Mark Chilla, Toby Foster, Abraham Hill, Payton Knobeloch, Josephine McRobbie, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week Ryan McGuire, Alex Chambers, Andrea Wiley, Christa Voirol, and Eric Schedler.

RENEE REED: Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from Toby Foster and from the artist at Universal Productions Music. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey.