(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington Indiana, I'm Kayte Young and this is Earth Eats.

JILL BROCKMAN-CUMMINGS: I think bread is more than food and it brings people together and it is the stuff of life.

KAYTE YOUNG: This week on our show, all about grain. We revisit a conversation from the spring Jill Brockman Cummings and Harold Wilkin at Jaime's Farm and Mill about flour scarcity in the pandemic and the wisdom of short supply chains. And we learn about kamut, an ancient grain with a great story enjoying renewed popularity, plus instructions for getting started with sourdough bread baking at home. That's all coming up in the next hour here on Earth Eats, so stay with us.

(Piano Music)

KAYTE YOUNG: Earth Eats is produced from the campus of Indiana University in Bloomington Indiana. We wish to acknowledge and honor the indigenous communities native to this region, and recognize that Indian University is built on indigenous homelands and resources. We recognize the Miami, Delaware, Potawatomi, and Shawnee people as past, present, and future caretakers of this land.

Renee Reed is here with Earth Eats news. Hello Renee.

RENEE REED: Hello Kayte.

A torrential rainstorm in August knocked over corn stalks across much of Iowa and parts of Illinois. At the time a big question was how much of those damaged fields would yield any crop at all. As the harvest wraps up, there are no clear answers. More than 3 million acres of corn in Iowa alone got slammed by winds up to 100 mph. Some stalks fell almost flat to the ground. Many others remain standing with a pronounced tilt. Key cooperative agronomist Ben Holing said some farmers terminated the crop to focus on preparing fields for next year, but many attempted to harvest some of their damaged corn.

BEN HOLING: Some of it they might only got half of it picked up, some of it they did a little better. Was it a hybrid was its technique? You know they kinda got what they got and there's an infinite number of variables.

RENEE REED [NARRATING]: He's telling farmers not to read too much into this year's data when planning for 2021.

Much of the great plains is experiencing drought, and a lack of fall rain could spell problems for farmers in the spring. After a muddy harvest last year some plains farmers are relishing being done by Halloween. With crops almost in, Brian Fuchs at the National Drought Center says the soil has one job now: recharge.

BRIAN FUCHS: Any moisture that we can add into the soil now before the soils freeze up is going to be moisture that is available next spring when we plant that next crop.

RENEE REED [NARRATING]: Regional weather is skewing warm and dry right now, if conditions don't change some crops could struggle next season.

BRIAN FUCHS: I'm pretty nervous about where we're going into the 2021 production year. Out in the western Nebraska winter wheat is implanted into some fairly dry soils, you know that crop is off to a poor start.

RENEE REED [NARRATING]: Given the La Nino weather pattern, southern states are likely to stay dry while the north sees snow and rain.

Thanks to Christina Stella and Amy Mayer of Harvest Public Media for those reports. For Earth Eats News, I'm Renee Reed.

(Earth Eats news theme composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

(Gentle guitar music)

KAYTE YOUNG: If you like to bake at home, whether it's cookies, banana bread, biscuits or even just pancakes, how's your flour supply holding up? At the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, flour was hard to come by in the grocery store.

JILL BROCKMAN-CUMMINGS: This large food supply chain is not equipped to deal with the surge in demand for small like 5-10lb packages of flour. They were supplying huge amounts to huge bakeries or facilities, and when everyone wanted to bake at home because they needed to stay at home and they needed food, they couldn't just adapt quickly to creating more small packages for the consumers.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: I spoke with Jill Brockman-Cummings and Harold Wilkin of Jaime's Farm and Jaime's Mill in Ashkum Illinois, it's about an hour and a half due south of Chicago.

HAROLD WILKEN: We're really one of the only mills of scale in the Midwest.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Harold is the farmer, founder and CEO. Jill is the head miller. At Jaime's farm they grow organic grains like wheat and rye. They also grow corn and soybeans, but they're grown for food.

HAROLD WILKEN: One of my goals when I went organic was to feed people.

JILL BROCKMAN-CUMMINGS: And Harold is one of the few farmers in the Midwest that does produce food to feed people rather than what's commonly grown in this region is crops for ethanol and to feed animals. So to feed people grains - healthy grains is unique in this region.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: The mill is located just down the road from the farm. It's the newest part of the operation. They sell whole grains to other mills in the Midwest and for the past three years they milled their own flour as well. I've been hearing about Jaime's grains and flours from local baker Eric Schedler of Muddy Fork Bakery. Jaime's uses stone mills to grind their grain.

JILL BROCKMAN-CUMMINGS: All of our flours are considered whole grain as all three parts of the grain are in it, the germ, some of the bran and the endosperm which is the white fluffy part.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: When you use a stone mill, you can't remove the germ from the flour, that's the center of the grain with the oils and the nutrients. To produce a lighter variety of whole grain flour, they shift it to remove some of the bran. The bran is the outer part of the kernel with all of the fiber, but they remove all of it.

JILL BROCKMAN-CUMMINGS: All of those things, the bran, the germ, those bring flavor and that's one of the reasons that people really love our flours is they're just so much more flavorful.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Since the coronavirus hit the U.S., Jaime's experienced a huge shift in their sales.

JILL BROCKMAN-CUMMINGS: We were focusing on wholesale bakeries and restaurants up in the Chicago area, and in this Midwest region. And then when the coronavirus pandemic hit and we had an amazing rise in retail sales then everything kinda got turned upside down, and we were, well we still are focusing mainly on our online retail orders. For a week we were at over 500 orders a day whereas prior to this we were on average 10 orders a day. So yeah the increase was unbelievably steep.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: They've had an average increase in retail flour sales of 3000%. So what's happening here? Why such a dramatic change? And what does it say about our food system? Jill and Harold have some thoughts on that.

JILL BROCKMAN-CUMMINGS: People are thinking more about the supply chain and how Americans get food on their table. I think the coronavirus pandemic has brought to light that the long global food supply chain failed and that a simple supply chain like the one at Jaime's Farm and Jaime's Mill can withstand pandemics or other problems that might occur in our system. And I think people are appreciative of that. And I think that people are thinking more and more about like where their food comes from, and that's been reflected in other areas as well. I think a lot of people are looking at FSAs for their fruits and vegetables this summer. I think finally consumers are realizing that the food system we had was not the best.

HAROLD WILKEN: We take our soybeans and our wheat out of our business. We clean them. And then they good right away to be made into food whether it's milling flour or it's making tofu, you know people can eat this. They don't have to rely on going to Walmart, they don't have to have somebody with a thousand miles away to mill grain so that they can bake. It's right here. And we can adjust to what they need.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Jaime's Mill has managed to keep up with the increased demand. They've hired new employees, they're now running both of their mills around the clock and they purchased new packaging equipment to increase efficiency. I was wondering about the grain supply itself, did they grow enough?

HAROLD WILKEN: We have plenty of grain, we have planned ahead so that we would have enough grain. A wise miller once told me have at least a half of your next year's needs in grain in your bin so in case something happened you were able to keep customers taken care of. And that was good advice.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: I asked Jill and Harold if there was anything else they wanted to say about the unprecedented consumer demand for flour during the pandemic. Harold thought there might be a mental health aspect to it too.

HAROLD WILKEN: A lot of people find comfort in baking when other things are uncertain, they feel like they're doing something. Some of them are sending loaves over and putting them on neighbor's porch, or cinnamon rolls, or whatever and (inaudible) to take care of one another, and by doing baking they are able to give back to other people.

JILL BROCKMAN-CUMMINGS: I think bread is more than food and it brings people together and it is the stuff of life, and I think in these uncertain times it's on our honor and our privilege to supply the good food.

KAYTE YOUNG: That was Jill Brockman-Cummings and Harold Wilkin of Jaime's Farm and Jaime's Mill. Find out more about their grains and flours at EarthEats.org.

I'm Kayte Young, this is Earth Eats. After a short break we'll hear about what farmers might be looking for in the upcoming presidential election, plus a fun story about how an ancient grain made it to the fields of Montana. Stay with us.

(Transition music)

Agriculture policy isn't getting much attention in the runup to the presidential election, but farmers are looking closely at what they might be able to expect from four more years of Donald Trump, versus a Joe Biden administration. Harvest Public Media's Jonathan Ahl reports there aren't a lot of solid answers and any difference may not matter anyway.

JONATHAN AHL: Jim Mulhern says he's often asked what the next four years will be like depending on who wins the presidential election. The president of the national milk producer’s federation says that really depends on how the candidates will treat trade. Mulhern says President Trump has created a mixed bag for farmers with a series of tariffs that have led to retaliation and a trade war with China and other countries.

JIM MALHERN: Look the President has been very clear, he sees the approach he's taking, this hardline approach as one that it is my worse. And I think it's likely to probably continue. We have no reason to expect anything different.

JONATHAN AHL: Mulhern says those trade policies have hurt many farmers but they tend to support the overall goal of holding other countries accountable and looking for better deals. In terms of Joe Biden, Mulhern says it's less clear.

JIM MALHERN: None of us can give a real strong view of what a trade policy would look like by the Biden administration other than likely to be attempts to do trade agreements like we've done in the past.

JONATHAN AHL: Specifically during the Obama administration when Biden was Vice President and Tom Vilsack was the secretary of agriculture. Biden has presented his plan for rural America, which includes general language about trade policies that work for farmers in promoting biofuels. That's exactly what Pam Johnson wants to hear. She and her family grow soybeans on 1000 acres in Northern Iowa. She says she can't make it without a U.S. commitment to ethanol and other biofuels.

PAM JOHNSON: My farm's success and ability to survive depends on support of that market, that domestic market.

JONATHAN AHL: Johnson says that tariffs that end up reducing her access to foreign markets also hurt. President Trump has been hard on ethanol until September when he announced a policy approving use of existing filling station pumps to distribute higher ethanol gasoline. Johnson says it's too little too late and she's voting for Biden.

But Scott Long says even though President Trump doesn't know a lot about agriculture, he has surrounded himself by people who do. Long who raises cattle on 1000 acres in southern Missouri and owns a 10 employee meat processing operation, says he likes Secretary of Agriculture Sunny Perdue's commitment to reducing regulation.

SCOTT LONG: As long as people have the right to farm, and the right to run cattle or hog, sheep or whatever they want to do, we need people in there that are gonna respect that. And I think Sunny Perdue has that type of attitude toward it.

JONATHAN AHL: Long says Trump's hardline on trade will be worth it in the long run to all Americans including farmers and he supports the administration's policies. But the farm vote may not mean much this selection. David Kimball is a political science professor at the University of Missouri Saint Louis, he says rural voters overwhelmingly supported Donald Trump in 2016 and will again regardless of how they feel about his agriculture policy.

DAVID KIMBALL: A lot of rural voters are not farmers necessarily, neither so the people working in the AG industry is a fairly small portion of the American electorate. Which is I think is another reason why agriculture policy may not be of mind for many voters.

JONATHAN AHL: Kimball says the only way AG might be the difference is if the election comes down to one or two swing states with large rural areas. But with issues like coronavirus, the economy and supreme court nominations looming large, agriculture issues won't get much attention between now and November 3rd. Jonathan Ahl, Harvest Public Media.

KAYTE YOUNG: The reporting collective at Harvest Public Media covers food and farming in the Heartland. Learn more at HarvestPublicMedia.org.

(transition music)

(Gentle guitar chords)

Earlier in the show, we spoke with a grain farmer and a miller in Ashkrum Illinois. Next producer Alex Chambers has a story about an ancient variety of wheat with a good backstory.

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: The story starts at an American air base in Portugal. It's 1949, and there's a pilot from a farm in Fort Benton, Montana. He's chatting with another American, who says "Hey, check this out. I was just on furlough in Egypt. I got into one of the old tombs. Not too far from the pyramids, you know. And I found something. Here." And he drops thirty-six seeds into the pilot's hand. The pilot grew up on a farm, so he knows it's wheat, but the kernels are a lot bigger than he's used to. He mails them to his father, back home. His father plants them. Thirty-two of them come up. He replants their seeds and in a few years, he has bushels. A mailman gets ahold of some and starts passing it out to all his customers, calling it King Tut's wheat. Bob Quinn was a teenager at this point, growing up on a farm in the 1960s. One day, he went to a county fair in Fort Benton.

BOB QUINN: and I saw this old fellow passing out something, and he called me over and said, "Hey sonny, would you like some of King Tut's wheat?" and I said "Sure" and he poured this handful of grain in my hands, and it was giant. It was about three times the size of the wheat I was familiar with growing on our farm. And the story was that it came out of a tomb in Egypt, and that was quite a novelty. And everybody kind of wowed over it, but nobody did anything with it past being a novelty and I pretty well forgot about it,

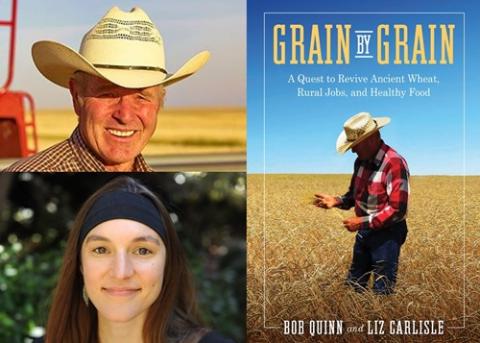

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: Until years later that is, when it would give Bob new insights into how modern wheat might be affecting people's health and help him transform the farm economy of north-central Montana. Bob started out as a strong believer in chemical farming. He even got a Ph.D. in plant biochemistry. But then he went back to the family farm, and he's been farming organically for thirty years. He served on the first National Organic Standards Board, and among other things, he started a company that sells that ancient wheat, which he calls Kamut. Maybe you've heard of it. Bob also has a book out, called Grain by Grain, that he co-wrote with Liz Carlisle.

LIZ CARLISLE: So I'm Liz Carlisle. I am also a Montanan, left the state at 18 but found myself back there visiting with organic farmers, and now teach and write about sustainable agriculture,

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: Because I bake a lot of bread, the part of the book I was most interested in was the ancient wheat. But it turned out that Kamut can tell us a lot about the wheat we eat today, and how we farm, and even about jobs, rural economies, and multinational corporations. But first, I want to get back to the story of that strange, ancient wheat. After the county fair, Bob forgot about it for years. Then one day in grad school,

BOB QUINN: I was eating a package of corn nuts, just idly in the hall one afternoon taking a little break and on the back of the package it said, "Corn nuts, made with a giant corn."

And I thought, "I wonder if corn nuts would be interested in a giant wheat,"

So I called them up, they were nearby in Oakland, and they said, "Yeah, we might be interested in that,"

And I called my dad right away, said, "Dad, see if you can find some of that old King Tut's wheat!"

And in a week or so he said he'd found the jar in a friend of his basement, and he sent a couple tablespoons to corn nuts and they loved it and said, "Wow, we'll take 10,000 pounds of this stuff, this is fantastic."

And I said, "Well, I don't really have 10,000 pounds." I didn't want to tell them I didn't even have one pound.

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: So he called his dad and said "Plant it all! Stat!" Okay, he probably didn't say "stat." They planted two crops a year for a few years and got up to fifty pounds. He called Corn Nuts again, but the guy he'd talked to was gone, and no one else was interested.

BOB QUINN: And so we just put it in the shed. And there it sat till about '86, when we went to our first health food show in California,

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: Where, out of the hundreds of people who walked by, only one showed any interest. But that one conversation led to a contract.

BOB QUINN: From that we planted the whole 50 pounds and 30 years later on half an acre and 30 years later we're up to 250 farmers all over Montana, Alberta, and Saskatchewan, all organic, planting over 100,000 acres. So that's how it blossomed. And I had no idea it would do anything like that.

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: But Bob still didn't really know where the grain came from. He knew it couldn't be from a four-thousand-year-old tomb, because it wouldn't have grown. So where could it have come from? What was this wheat? It got clearer after he started shipping to Europe. At a food show there

BOB QUINN: I ran into a fellow from Egypt and he invited me to Egypt

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: So he went to the Cairo museum and took a look at the wheat kernels that had been found in the tombs. It didn't look anything like his wheat.

BOB QUINN: And so I was pretty dejected. But I – bc we'd been telling this story for ten years or so.

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: But he kept trying to figure it out. On a trip to Turkey, people recognized it. They call it Camel Tooth, because the kernel has a kind of a hump on it. They told Bob they also said they call it the Prophet's Wheat.

BOB QUINN: and I asked them, "Why do you call it the prophet's wheat?"

They said – I said, "Does it have something to do with Mohammed?"

And they said, "Oh no, no, not that prophet, you know the one with the boat."

And I asked and said, "You mean Noah?"

And they said, "Oh yes, it's the grain Noah brought with him on the ark."

And I said "Wow, that's a lot better story than my old tomb story."

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: Although the tomb story is pretty good. In any case, after more sleuthing, he eventually figured out it was most likely a variety from the Khorasan region of Iran. He trademarked it as Kamut, an ancient Egyptian term for wheat. The trademark meant that any farmer who used that name had to grow it organically. As the grain became more popular, people who usually had problems eating wheat realized they could eat Kamut breads and pastas without their usual symptoms.

BOB QUINN: And I was very curious to try to figure out why that was so, what was different, what we had changed. And we had a hard time finding researchers in America that took seriously this claim. Most of them said "Oh this is just all in their head. People say they can eat one thing or can't eat another." But in Italy we found a very great interest in this question.

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: So they teamed up with researchers in Italy to see how rats were affected by diets of ancient versus modern wheat, and what they found surprised them. The rats eating modern wheat had a lot of inflammation, whereas the ones on ancient wheat had none. That was a big deal, because inflammation is a factor in a lot of chronic disease. Then they did clinical trials with human volunteers and had similar results. And it wasn't just inflammation. The groups eating ancient wheat had much lower cholesterol than the ones with modern wheat, even the people who were on medication.

BOB QUINN: So it was really an astonishing discovery, and it was so consistent, and every single person had similar responses that it really gave us a brand new picture of what we had done to modern wheat and its breeding program that changed the gluten and changed the yield potential and everything that we've been doing.

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: And if that's the case, if ancient wheat really is better for us, Liz Carlisle thinks we should listen to that.

LIZ CARLISLE: Wheat is trying to tell us something. This grain that we've had a longstanding relationship with in human societies, one of the first crops really, that we developed in the way we understand a crop, it's trying to tell us something about what's wrong with the food system.

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: From raising food with so many chemical to taking out the nutrients in processing, even how we breed our crops.

LIZ CARLISLE: A lot of the food we eat comes from a very small number of crops, and that small number of crops are the ones that have been bred really intensively for just a couple of goals: high yield, and in the case of wheat, high loaf volume. But along the way, people weren't really paying attention to things like nutrition.

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: And not just our bodily health, but also the health of our land and local economies. Liz says in industrial agriculture, most of the money doesn't go to the farmer, it goes elsewhere in the supply chain, like the fertilizer and pesticide and seed companies, and expensive machinery. At the other end of the food chain it goes to the processor.

LIZ CARLISLE: So as a result, you have these areas of the U.S., you're in one yourself, where there's a lot of agriculture, but not very much money is actually staying in that community with the farmers, or with the small businesses that farmers would support. Whereas with organic agriculture, essentially what I see is that instead of the money going to chemicals, the money is going to people.

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: So why isn't everyone switching to organic? Bob Quinn says it's partly because, for so many farmers, converting to organic is a step into the unknown. It's a big risk, and there's very little support from the USDA. But there are cultural pressures too. Major multinational corporations make a lot of money off the current system, and they don't have any real incentive to change.

LIZ CARLISLE: And also I think, you know in more nuanced ways in communities, they've been very sophisticated about getting to message out in rural America. But also in urban America where people eat, and convincing people that they really have the best interest of the farm community and the American public at heart.

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: Liz has seen some of the ways that major AG corporations have also created a cultural divide. At farm conventions and in rural advertising, they tell farmers that organic agriculture

LIZ CARLISLE: is a project of urban environmentalists and foodies who don't understand what's happening in farm country to insult and discount and disrespect the hardworking family farmer. And so, this messaging goes, it's really the chemical companies that have the farmers' interests at heart, understand what they're going through on a daily basis, and are gonna provide them the tools they need to deal with their problems.

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: Still, Bob and Liz are both optimistic. Bob's had more calls in the last eighteen months from farms wanting to convert to organic than in the last thirty years. And Liz says that addressing the issues in our food system is helping us achieve human potential,

LIZ CARLISLE: And really becoming what we're capable of in terms of the way we can care for each other and live in community and also steward and care for the rest of the planet.

ALEX CHAMBERS [NARRATING]: You can learn more about Kamut wheat and its role in the health of soil and local communities – and some of the new research on ancient versus modern wheat and how it affects our bodies in Bob Quinn's and Liz Carlisle's book - Grain by Grain: A Quest to Revive Ancient Wheat, Rural Jobs, and Healthy Food. It was pretty fascinating. We've got a link on our website.

KAYTE YOUNG: That story comes to us from producer Alex Chambers who has a new podcast of his own called The Age of Humans. We have a link to it at EarthEats.org.

(Transition music)

Coming up after a short break, a story about the risks migrant farm workers take to keep the food supply humming, and instructions for making sourdough bread and baking it in a hot cast iron pot.

(Pensive piano music)

Kayte Young here, this is Earth Eats. Millions of farm workers throughout the U.S. work every year to plant crops, harvest them, and do everything in between. Among them are migratory workers who leave their homes for months at a time to take on what's often a risky job. As Harvest Public Media's Dana Cronin reports, the coronavirus pandemic has made it even riskier.

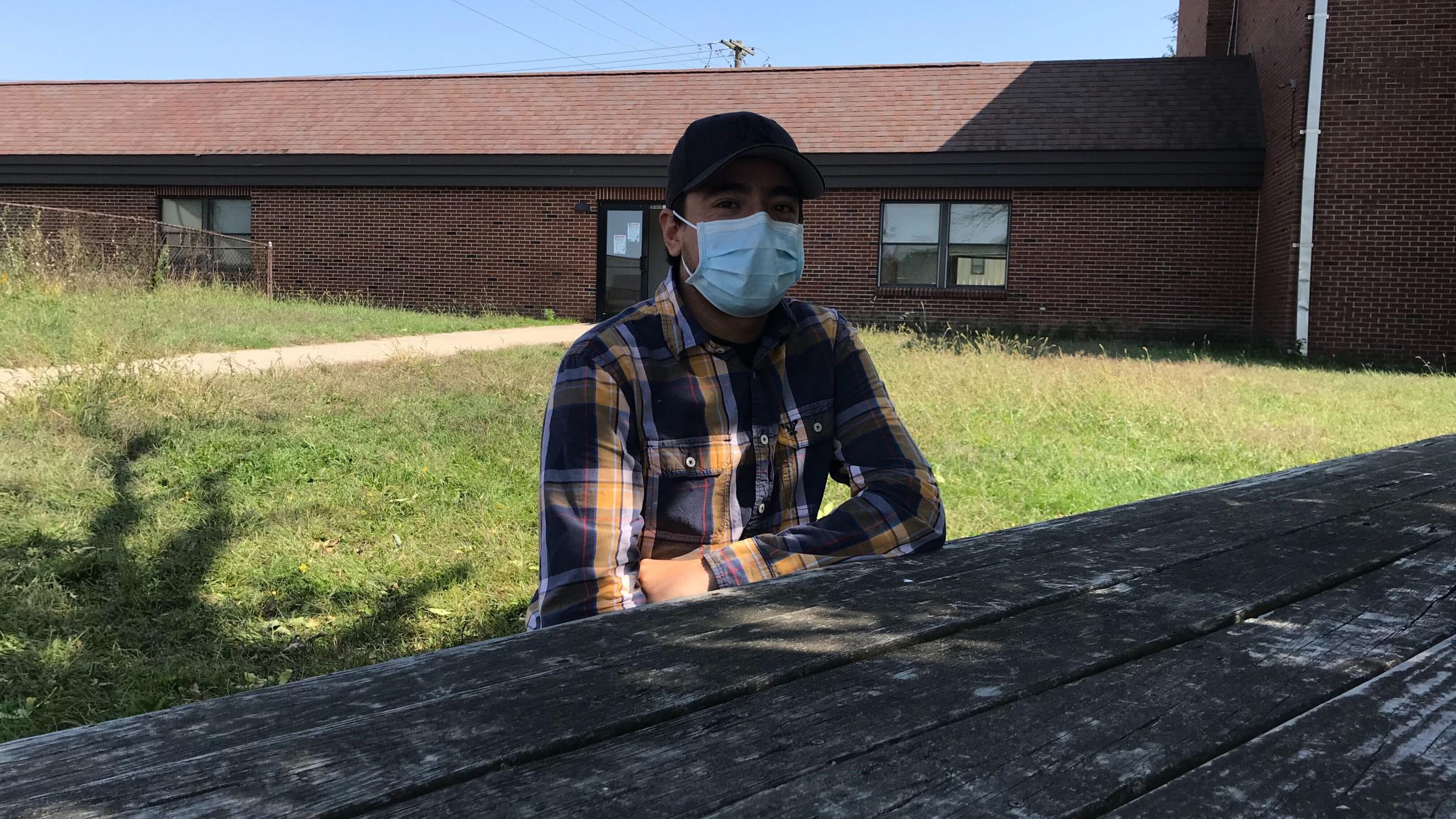

DANA CRONIN [NARRATING]: About a hundred migrant farm workers are living at an old hotel on the sleep outskirts of Rantoul Illinois. Every day at crack of dawn Samuel Gomez gets his temperature checked on the way out.

SAMUEL GOMEZ: Muy bien

DANA CRONIN [NARRATING]: The rest of the early morning crew loads onto a school bus for a 30-minute drive to a big warehouse, where they sort good from bad corn that comes in on a conveyor belt. Gomez is one of the lucky few with access to a car, so he drives there with his Dad and sister. He's been here all summer, starting in the corn fields. Now he's in the warehouse where he spends most of his day cleaning. It's never an easy job but the pandemic has added another layer of stress for these workers. Gomez has been traveling to Illinois as a migrant worker for four years, he lives in Mexico the rest of the year.

SAMUEL GOMEZ: (Speaking Spanish)

DANA CRONIN [NARRATING]: He says before arriving here in June, he didn't know anyone with COVID-19 and didn't think it really existed. Since June the local health department has linked 21 cases to the hotel where Gomez and an entire crew of migrant workers are living. Once he witnessed the outbreak firsthand he says the threat became very real.

SAMUEL GOMEZ: (Speaking Spanish)

DANA CRONIN [NARRATING]: He says he was scared and started taking it seriously. He began wearing a mask for the first time, using hand sanitizer and social distancing. But not only is he living with 100 or so others at the hotel, he’s also working at an indoor facility with them. He says there are fewer people working at the warehouse this year and everyone's masked, so he feels safe, but he also lives and works with his 66 year old dad, and says he worries about him.

SAMUEL GOMEZ: (Speaking Spanish)

DANA CRONIN [NARRATING]: He says all he can do is be cautious for himself and his family. 24-year-old Josh works at the corn processing plant too, we're only using his first name because he fears retaliation. He's an American, born and raised in Texas, and he grew up in this migratory lifestyle. His parents are migrant workers too. He says this year feels different, since the outbreak there's been less socializing, no cookouts or parties.

JOSH: It really feels deserted and it feels different. The air, you can smell the air in the mornings and it just feels way different. Like way different, it's not the same air I breathe that season. You feel it, you feel it.

DANA CRONIN [NARRATING]: He also says he worries about COVID but says he doesn't have a choice.

JOSH: Either I risk it all, or nothing at all. I want to leave something behind; I want to leave a print behind. I'm not gonna give up.

DANA CRONIN [NARRATING]: Many migrant workers make double what they could at home, it's a prospect they simply can't turn down says Sylvia Pardita, CEO for the National Center for Farm Worker Health.

SYLVIA PARTIDA: Economic necessity, I mean that's what it comes down to. This is their work, and they rely on this work to survive.

DANA CRONIN [NARRATING]: Her organization has documented COVID outbreaks among farmworkers in 17 states, including deaths in some states. But because there isn't an official tracking system, she says that's likely an underestimation. For migratory workers like Samuel Gomez and Josh, Partida says the risk of contracting the coronavirus is heightened; they often travel in large groups, live in congregate housing, and are unfamiliar with the local resources.

SYLVIA PARTIDA: There's been a lot of fear and a lot of uncertainty and relying on organizations that might be able to assist them as they try to learn how to safeguard themselves.

DANA CRONIN [NARRATING]: She says it's up to the federal departments of labor and agriculture to protect these workers, but until then they'll continue traveling to the next job and hoping for the best. I'm Dana Cronin, Harvest Public Media

KAYTE YOUNG: This story was produced in partnership with Side Effects Public Media's Christine Herman and the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting.

(Pensive piano music)

(Playful piano music)

Maybe you got your hands on some flour. It's been easier to find in recent months. What about yeast? Commercial yeast was scarce there for a while too. The good news is you don't need commercial yeast to make bread. You can make sourdough bread with wild yeast. I learned how to make sourdough from Alex Chambers who you heard from earlier in the show. Alex is really good at making bread. He's really good at teaching too. If you don't have an Alex Chambers in your life there are a lot of great bread tutorials out there right now, YouTube videos, Instagram.

When it comes to breadmaking though, there's no substitute for experience. You just gotta get in there and make some bread. If you can’t handle failure, this might not be the failure for you. You will fail. But usually the failures are edible, butter on freshly baked bread is almost always tasty and you'll learn from those less than perfect loaves. Trying and failing is the only way to find out what works, what doesn't, what fits with your schedule and your lifestyle and also what kind of bread you like.

I prefer what's known as a lean bread, rustic and crusty. My bread has three ingredients, flour water and salt. Okay, four if you count the starter and it's made from flour and water and wild yeast gathered from the environment. Here is my step by step, we're gonna assume you already have a starter. If you don't, not to worry, I'll post instructions for how to make one. It's not difficult, it just takes time. I started with one of the things I love most about this method.

The starter is tiny, it's a tablespoon. You can keep it in your fridge without doing anything for about two weeks, that's what's recommended, but I can tell you that I have left mine in my fridge for months and taken it out, and it's fine. So I'm gonna do that right now.

And I keep it in a small jar, like a little jelly jar. It smells... (sniffs) it smells really yeasty, it's acidic I think is a word I would use. Sometimes I feel like it smells a tiny bit like glue, like Elmer's glue. Not so much this time.

It smells pretty good and now I'm just gonna add a tablespoon of whole wheat flour, a tablespoon of white flour, and a tablespoon of water. And then you just want to mix it up really good, and I just leave it in the jar for this stage. And then to cover it I have one of these like really small shower cap type things that you can put over bowls like these old fashion bowl covers, looks like a little shower cap. If you don't have one of those you can just use some saran wrap or even probably just put a towel over it, it'd be fine.

I'm gonna leave it out for a few hours, I'm gonna check on it and see how it's doing.

(Playful piano music)

(Timer ringing)

Okay so it's time to check on our starter. I'll admit it has been more than two hours. But that's fine, this is a very flexible process. I've taken off the little shower cap. (Sniffs) It's always good to smell it. The other thing I'm doing is I'm looking at the jar and I'm seeing air bubbles on the side.

And I'm gonna take a spoon and kind of... I think you can kind of hear those air bubbles in there and that means it's alive. So it's doing its thing, it's growing. Now we officially have a starter, I basically built a starter by adding a little bit more flour and water to it, feeding it.

So now I have a starter and I can make the next stage which is called the leaven. And that requires half a cup of whole wheat flour, half of cup of white flour and half a cup of water, plus this starter.

So I scraped all of that starter out of the jar and I'm putting it into the bowl with the water, and then half a cup of whole wheat flour and half a cup of white flour.

I'm just gonna mix it up really well in a medium sized bowl, and once again I'm gonna cover it. And we're gonna let this sit out for a few more hours.

(Playful piano music)

(Timer ringing)

Okay we are back with our sourdough and we're at the stage of the leaven. We want to see if it has sufficiently fermented. So the way I'm gonna test this is I’m just gonna pull back on the bottom of the dough in the bowl. If you're seeing lots of air bubbles and it's starting to look kind of loose and webby on the bottom then that means your dough is alive, it is fermenting, and you're probably ready to move on to the next step.

The first thing you wanna do with this leaven is you wanna take a tablespoon of it out, and you want to put it in your starter jar and stick it back in your fridge. Now you are ready to make your dough.

Take your leaven that you've let rise, start by adding about a cup of the water to the bowl that the leaven is in. Just want to mix that in really good until it's nice and soupy. And you're gonna mix your dry ingredients in a large bowl. You can do whatever mix you want, I like to do about 5 cups of white bread flour, and one cup of whole grain flour. Sometimes I'll do half and half, very flexible. And I have some special flour, whole grain flour that I got from Muddy Fork Bakery, and they got it from Jaime's Mill. This is stone ground, high protein, whole grain flour. I think this particular whole grain flour has been shifted to extract some of the bran, so it's gonna be a little bit lighter than your typical whole grain flour. I'm excited to try it.

So you got your six cups of flour, one tablespoon of salt, and then the leaven that you've mixed with the water, and then two more cups of water. You're gonna mix all that into one bowl. And that is gonna be your big shaggy mass as Alex calls it. And that's gonna be your dough. And it's not gonna look like a shapeable bread dough. At this point it's just gonna be a wet shaggy mass, and that's fine.

Once it's thoroughly mixed you're gonna cover it with some plastic wrap, or a damp cloth and we're gonna let it rise some more. You're gonna want to set a timer, every half hour, every 45 minutes, you're gonna wanna fold this dough. Which basically just means pulling up a corner and folding it over and spinning a quarter turn, pulling it up, folding it over, spinning it a quarter turn, and doing that four times. And then cover it back up and leaving it and setting another timer. You want to keep doing this, you don't want to forget, so set a timer.

(Playful piano music)

(Timer rings)

And then when you are ready for your final proof, you want to dust your surface, a surface in front of you on your countertop with some flour. And then dump your dough out onto that surface. And you want to divide your dough in half. This recipe makes two loaves. And again you're just gonna want to do some folding to shape it.

Shaping is hard to explain. Press your dough out and then pull at the edge, the edge furthest away from you and fold it into your dough. And then pull up the edge closest to you, fold that into the middle of your dough. Do that with that with the right and left as well, and then turn the whole thing over and hold it in your hands and kind of move it around on the surface to create sort of a tension across the top of your dough. The tension is really important it really helps with the oven spring.

With the shaping, I recommend that you watch people doing this. You can't learn this from a description on the radio or from a book, I found that watching people in person or watching videos of people shaping bread is very useful. Just pick one you like and watch it over and over. Then get to your dough and try it out for yourself.

And then you'll want to set that on a piece of parchment paper that is lightly dusted with flour, and let it rest for 20 or 30 minutes.

You're gonna want to be getting your oven heated up, and you'll want to heat up a Dutch oven. This is a Dutch oven process. And then shape your second loaf and set that on the parchment, and make sure you get your oven heated up. You wanna preheat your oven to 500. That's as high as mine goes, if your goes higher than that, go for it. You want to put the Dutch oven into the oven. I just leave the lid on and then just let that preheat, make sure you press start.

(Playful piano music)

(Timer ringing)

Now that your shaped loaf has risen you are ready to get it into the preheated oven, I'm using a Dutch oven which is a cast iron pot. This one is an enamel lined, and it has a lid and it's a really great way to bake bread. It creates a miniature steam oven that allows your loaf to get a really great oven spring, to really rise and get that nice crusty exterior.

This recipe relies on the use of a Dutch oven, if you don't have one it makes this method harder but not impossible. I'll share instructions on the website for how to get steam into your oven to help with the oven spring and the crusty crust.

And now I'm ready to get my loaf into the Dutch oven, the problem is the Dutch oven is very hot and it's heavy. So you need to be really careful for this step, and you need to kind of set everything up. So what I do is I set up some kind of a trivet on my countertop that I can set the Dutch oven on. And then I bring my loaf over, my shaped bread loaf is now ready on the countertop next to my trivet. And I now have two very thick potholders, and I'm gonna pull that Dutch oven out of the oven.

Okay so I'm going to now carefully lower this shaped loaf into the Dutch oven. And the next step, the final step before getting it into the oven is scoring the top of the loaf. This is honestly not necessary in the Dutch oven, it will be fine if you don't score it, but it can be a fun extra step. So you want to take a very sharp knife or a razor blade and just quickly and decisively slash across the top of your shaped loaf, being careful not to touch the sides of the Dutch oven and not to get burnt. Once you have lowered the shaped loaf into the cast iron pot, grab your very thick potholder and put your lid back on. Make sure you have two potholders ready, open your oven and get that Dutch oven back in.

(Playful piano music)

Once it's in the oven, reduce the heat to 450. Set your time for 35 minutes, about halfway through remove the lid from the Dutch oven.

(Timer rings)

Once your timer goes off remove the Dutch oven and dump the bread onto a cutting board or cooling rack.

(Sound of bread thump thump thumping)

Then you want to thump it and see if it has sort of a hollow sound. You want it to have a nice golden-brown crust, you do not want a pale loaf of bread. You want it to have a really nice browned exterior.

This is the really hard part, leave your bread out on the counter, on the cooling rack, for about an hour before cutting into it. This is tough because it smells incredible and it has this kind of crackling sound when it first comes out that's really nice. It's very tempting.

But you need to understand that the bread is still cooking, and if you cut into it at this point it's gonna be dough and it's gonna gum up your bread knife, and it's just a mess.

Really try to wait that full hour, and then cut into it, what I like to do is just cut straight down the middle of the loaf, I find it easier to deal with the loaf when it's in half. Plus you get a really good look at the center of your loaf, and you can see if it's got those nice air bubbles that you were hoping for and you can really inspect the crumb.

As far as storage goes, leave it out on the counter until it's fully cool. After that you're gonna want to store it either in a paper bag or in a plastic bag. Once you get it in a plastic bag you are gonna get rid of some of that crunchy crust, but it will also possibly stay fresh longer.

That's my method. I hope it inspires you to bake some bread. Even if you don't try my method I hope you'll find a recipe or YouTuber or someone to follow to get you started. It truly is a satisfying hobby. You can find my instructions at EarthEats.org.

(Funky music)

Make sure you never miss an episode of Earth Eats, subscribe to our podcast. It's the same great stories in your podcast feed. Just search for Earth Eats wherever you listen to podcasts. And while you're there, please leave us a review. We love to hear from you, and it helps other people find us. Also did you know you can ask your smart speaker to play Earth Eats? Yup, that works too.

(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

That's all we have time for today. I'm Kayte Young, thank you for listening to Earth Eats.

RENEE REED: The Earth Eats team includes Eobon Binder, Mark Chilla, Abraham Hill, Josephine McRobbie, the IU Food Institute, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week to Jill Brockman Cummings, Harold Wilkin, Alex Chambers, Bob Quinn and Liz Carlisle

RENEE REED: Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from the artist at Universal Productions Music. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey.