“I remember seeing John Coltrane standing with one foot against the wall eating Sunkist raisins," David Baker said of the Russell group's debut at New York City's Five Spot. "I saw J.J. Johnson, Miles Davis, and Thelonious Monk there. It was the first time I’ve been frightened out of my wits, because they came to see what George was doing. We were all under intense pressure.”

1959 was an incredible year in jazz. Miles Davis recorded his masterpiece Kind Of Blue; Bill Evans revolutionized the piano-trio format; Dave Brubeck recorded his best-selling experiment in time signatures, Time Out; Charles Mingus waxed the landmark LP Mingus Ah Um; Ornette Coleman rocked the jazz world with his free-jazz quartet; and it was also the year that jazz theorist George Russell met the young, up-and-coming trombonist, composer, and jazz educator David Baker.

Russell had made his mark in the 1940s with compositions such as “Cubana-Be, Cubana-Bop” for Dizzy Gillespie’s big band that helped introduce the concept of modality into the jazz scene, and his development of his Lydian theory of composition, which expanded the use of scales improvisation, would point the way to Kind Of Blue. Baker had been leading a hardbop group in Indianapolis and a big band at Indiana University that had attracted the attention of musician and scholar Gunther Schuller, who wrote an article about Baker and the Indiana jazz scene for Jazz Review Magazine, and who arranged for Baker and some of his Indiana cohorts to study at the Lenox School of Jazz in Massachusetts. Lenox was an annual summer institution in the late 1950s and early 60s that hosted notable artists as both teachers and students, and it became a launching pad for the ideas of both Russell and Ornette Coleman.

David Baker resisted Russell’s teachings at first. “We were all coming out of a bebop mind-set,” he said. “He used to try to explain Ornette Coleman’s music to us and I would fight him on it. Almost every day I would challenge George, but he was very patient with me. I was really threatened by this new music.”

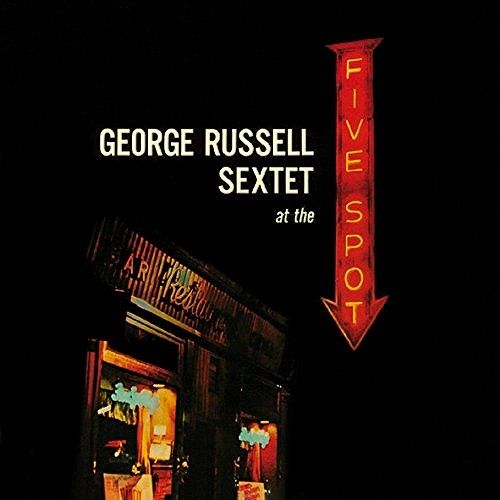

Russell said that the “energy” of Baker and his youthful Indiana cohorts was what inspired him to enlist them for his first working group. “There is a time in the development of young people when they’re really excelling, really reaching,” he said decades later, “and it’s that input that I can hear and compose for.” Russell went to Indianapolis and rehearsed vigorously with Baker’s combo, including tenor saxophonist Young, trumpeter Kiger, and drummer Joe Hunt from Baker’s IU big band. With the later addition of bassist Chuck Israels, Russell now had a working group and vehicle for his writing for the first time in his career. Gigs at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and at the Lenox School preceded a run in the autumn of 1960 at New York’s Five Spot, an already-legendary Bowery bar where jazz luminaries such as Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, and Cecil Taylor had all performed, not to mention Ornette Coleman’s quartet making its Big Apple debut there in 1959. Soon afterwards, the group made its first studio recordings. Here's the George Russell group performing Russell’s composition “Swingdom Come,” on Night Lights:

The George Russell Sextet performing Russell’s composition “Swingdom Come,” with Russell on piano, David Baker on trombone, David Young on tenor sax, Al Kiger on trumpet, Chuck Israels on bass, and Joe Hunt on drums, from the album At The Five Spot—a studio album that reflected the repertoire the group had been playing at the club of that name that was such a vital center of New York’s circa-1960 jazz scene.

The Five Spot performances drew significant attention from New York City’s jazz notables. In a 2010 interview with me Baker said, “I remember seeing John Coltrane standing with one foot against the wall eating Sunkist raisins. I saw J.J. Johnson, Miles Davis, and Thelonious Monk there. It was the first time I’ve been frightened out of my wits, because they came to see what George was doing. We were all under intense pressure.”

Baker also had to step up his writing game, with Russell asking him to contribute an unusual blues to each of the five albums that Russell would record in the early 1960s. One such composition, “Kentucky Oysters,” led Russell to coin the term “21st century soul music” to describe the evolving sound of the group. It also led to a signature Baker innovation, of playing the trombone in 4/4 time while the rest of the group adhered to 3/4. From the George Russell Sextet’s second album, Stratusphunk, here’s “Kentucky Oysters,” on Night Lights:

George Russell-David Baker "Kentucky Oysters"

The George Russell Sextet performing David Baker’s composition “Kentucky Oysters,” with Russell on piano, Baker on trombone, David Young on tenor sax, Al Kiger on trumpet, Chuck Israels on bass, and Joe Hunt on drums.

The Sextet was a mission for Russell. In a February 1961 DownBeat profile of him and the group, Russell said “We are out to prove that soloists can be oriented to play freely with or without chords. I want and try to create the climate for the players to reach for something more, to play out. This is not a play-it-safe band. There is too much of that sort of thing around today. Much that is mediocre is perpetuated. This can only crush the spirit of jazz.” Russell went on to say that “the old and new in jazz are combined in our work… we’re trying to express life… you can’t stay on one level or negate any kind of expressive technique.” Russell had begun to develop his compositional ideas in the late 1950s on the ensemble albums New York, New York and especially on Jazz in the Space Age, the latter marking his first use of several of the Indianapolis jazz musicians. Around that time he also wrote the tune “Stratusphunk,” but he didn’t record it until his small group’s sophomore studio outing, which ended up using the title of the piece itself, a piece Russell described as “a 12-bar blues that reaches far out into the 12-tone scale. The George Russell Sextet and “Stratusphunk,” on Night Lights:

The George Russell Sextet performing the title track from their 1961 album Stratusphunk, with Russell on piano, David Baker on trombone, David Young on tenor sax, Al Kiger on trumpet, Chuck Israels on bass, and Joe Hunt on trombone.

I’m featuring the music of George Russell’s early-1960s progressive-bop group on this edition of Night Lights, a group that initially featured four Indiana jazz musicians—trombonist David Baker, saxophonist David Young, trumpeter Al Kiger, and drummer Joe Hunt, the core of a Baker-led Indianapolis combo. "When George came into the group, he completely changed the coloring because, first of all, he had a whole area of new music, his own music," Baker told DownBeat writer Don DeMichael in 1964. "He wanted us to use all the colors--to use Dixieland, modern jazz, things borrowed from other musics... He encouraged us to play freely--this was the time Ornette Coleman had begun to make an impact, and George was the first to formalize the concepts Ornette had been using... George wrote tunes that were freer. But though there would be a general chord scheme, we would use (his) Lydian concept, which would have, say, nine scales. So we could color, using this or that scale each of which has its own implied dictatorial way of playing. But even at that, with nine choices you have considerably more freedom than if you ran the four of five notes in a chord."

Learning to play this music was hard work. "We rehearsed every day," Baker told me in 2010. "We would get off from work (playing in a club) at 2 a.m. At 1 p.m. the next day, we rehearsed both the new music and the old music. So we really lived with the music to the point that we could anticipate what George was looking for and he also knew what to write for each of us that would realize his perception and conception of what it should be."

The group received good notices after its 1960 debut in New York City, with George Hoefer in DownBeat saying that “the playing of the Russell sextet narrows the gap between free-blowing jazz and written chamber jazz.” Decca recorded the Russell combo three times in six months, producing the albums At The Five Spot, Stratusphunk, and Kansas City, the latter a studio representation of what the group had played recently in the city itself, much like the Five Spot LP. For Kansas City David Baker once again contributed an unusual tune, “War Gewesen,” which Russell biographer Duncan Heining describes as “a tricky, episodic and slippery blues that moves through changes in time, yet with an almost burlesque quality to it." The George Russell Sextet and “War Gewesen,” on Night Lights:

The George Russell Sextet performing David Baker’s composition “War Gewessen,” with Baker on trombone, David Young on tenor sax, Don Ellis on trumpet, Chuck Israels on bass, and Joe Hunt on drums, from Russell’s 1961 album Kansas City.

Though the group had begun as a vehicle for Russell’s compositions and featured Baker’s as well, it also drew on the compositions of non-members such as Miles Davis and the then still-little-known Carla Bley. A psychiatrist had suggested to Bley that she find work as a seamstress; instead she gave a piece of her music to Russell, who liked it so much that he recorded it and solicited further contributions from her. It was just another way in which the Russell group served as a kind of laboratory for some of what would follow in the modern jazz scene. We’ll hear two Bley compositions performed by the group now, the first a live recording from the Lenox School of Jazz in 1960, on Night Lights:

The George Russell Sextet performing Carla Bley’s “Rhymes,” with Russell on piano, David Baker on trombone, David Young on tenor sax, Don Ellis on trumpet, Chuck Israels on bass, and Joe Hunt on drums, from the 1961 album Kansas City. The same group before that, with Al Kiger on trumpet instead of Ellis, performing Bley’s “Dance Class” live at the Lenox School of Jazz in 1960.

Al Kiger had departed the Russell group shortly before the recording of Kansas City, and fellow Indiana musician David Young would soon follow. According to Baker and Hunt, who both stayed on, Kiger and Young had trouble adjusting to the pace and nature of life in New York City. Russell recorded his next album, Ezz-thetics, with Eric Dolphy on alto sax, then brought in two other Indiana saxophonists, Paul Plummer and John Peirce, for the follow-up, The Stratus Seekers. The Russell group’s final studio album, The Outer View, recorded in late 1962, featured no Indiana musicians, with Baker displaced by jaw issues that would force him to give up playing trombone, though he would go on to cement a significant legacy as a jazz educator. The Russell group’s legacy was significant as well; in the course of two short years, this combo, led by a jazz theorist who’d never had a working band before, and made up mostly of young Indiana jazz musicians who could hang with Russell’s steep modern learning curve, left behind a run of albums that helped point the way for where jazz would go in years and decades to come. I’ll close with an Al Kiger composition that the Russell group recorded after his departure, “Kige’s Tune":

Further listening:

Making A New Kind of Scene: New York City's Five Spot

...and reading: The Basics of David Baker: A Conversation

More music from the program: