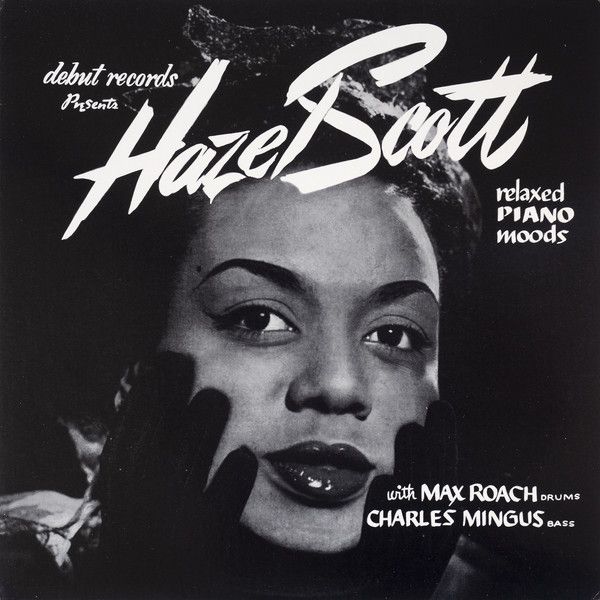

Scott's 1955 album with bassist Charles Mingus and drummer Max Roach is considered a high point in her discography.

Pianist Hazel Scott was a prodigy who rose to fame in the 1940s, swinging classical compositions, appearing in Hollywood movies, and becoming the first African-American to host a TV show. From the mid-1940s through the mid-1950s she and her husband, Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., were a glamorous African-American power couple. But Scott’s independent spirit and her civil-rights activism brought her career-damaging trouble that eventually sent her to Europe and caused her high profile to recede in the last several decades of her life. It’s “To Be Somebody: Hazel Scott”… coming up on this edition of Night Lights.

Have you heard of Hazel Scott? She was one of the biggest African-American stars of the 1940s, a young pianist and singer who wowed the sophisticates of New York City with her jazz-influenced performances of classical pieces, played a mean boogie-woogie, and was glamorous enough to appear in five Hollywood films. In 1945 she married Adam Clayton Powell Jr., a Harlem minister who’d just been elected to Congress, and they became a black American power couple, noted for their civil-rights activism as well as their society life. In 1950 she became the first African-American woman to host a television show. Who was Hazel Scott, and why is it likely that you haven’t heard of her?

Hazel Scott was born in Trinidad on June 11, 1920. Her parents moved to Harlem when she was four, and she came of age during the vibrant era of the Harlem Renaissance. From the age of three she was a piano-playing prodigy, and her mother was able to arrange an audition for her at the Julliard School when she was only 8. One Julliard professor, hearing her performance of a Rachmaninoff piece, declared that he was in the presence of “genius.” Despite her age, she was admitted to Julliard as a private piano student.

Over the next few years Scotdt honed her classical skills, but she also breathed in the heady influences of the swing-era jazz music that was all around her. Her mother Alma, who had been a classically-trained pianist, took up the saxophone and played in several all-women bands, including one led by Louis Armstrong’s ex-wife Lil Hardin Armstrong, and her circle of friends included some of Harlem’s most notable jazz musicians. Hazel Scott benefitted from direct contact with pianists such as James P. Johnson and Willie the Lion Smith. Eventually Alma formed her own all-women band, and a teenaged Hazel Scott became the group’s pianist. She made her stage debut under her own name at the age of 15 opposite Count Basie’s big band at New York City’s Roseland Ballroom. As a teenager she appeared regularly on New York’s WOR radio station and won a part in the 1938 Broadway revue Sing Out The News. Not long after, while working as an intermission pianist at the Yacht Club, Scott began to experiment with “jazzing the classics”—syncopating well-known classical pieces and improvising on their melodies, a practice that merged her classical training and her firsthand musical experiences in the 1930s jazz world. In 1939 a family friend and protector, singer Billie Holiday, gave up her long-running gig at Café Society, a hip, European-style leftwing cabaret that was one of the first Manhattan venues to open its doors to integrated audiences. Holiday all but demanded that her gig be given to Hazel Scott; and Scott’s subsequent performances drew a following, as well as the attention of jazz writer and promoter Leonard Feather, who arranged Scott’s first recording date. From that session here’s Hazel Scott with “Calling All Bars":

Café Society was a launching pad for Scott’s subsequent career, and her ability to “jazz the classics”—playing classical pieces by composers such as Chopin and Rachmaninoff with jazzy runs and flourishes—quickly won her a following. Scott was not the first artist to “jazz the classics”—the trend had been around since the 1920s. But nobody seemed to pull it off as convincingly as Scott, who was well-served by her jazz-and-classical pedigree, inherited from her mother and developed to a new level of performance. Here’s her 1940 recording of the same piece that had stunned Julliard faculty members at her 1928 audition—Rachmaninoff’s “Prelude in C Sharp Minor":

Though Scott rose to fame in part on her “swinging the classics,” as her first collection of recordings was titled, she more than held her own as a jazz pianist. She counted Art Tatum and Fats Waller among her friends and influences, and saxophonist and jazz giant Charlie Parker was also apparently a fan… many years after his death a recording surfaced of him playing along to Scott’s version of “Embraceable You":

Scott was not just a talented musician; she was an engaging and photogenic performer. Having already appeared in several Broadway productions, in 1942 she headed to Los Angeles and signed a contract with RKO, where Orson Welles tapped her to co-star with Louis Armstrong in a history-of-jazz film that sadly never came to pass. Scott immediately had to contend with the racist mores of Hollywood…the first four roles offered to her were all of singing maids. She turned them down. She insisted on presenting herself in her subsequent five film appearances as Hazel Scott, an elegantly-attired musician of considerable prowess. Her playing of two pianos at once in the 1943 film The Heat's On would inspire Alicia Keys to emulate and namecheck her at the 2019 Grammy award show:

That same movie, however, proved to be Scott’s undoing in Hollywood. For one number, she was to play and sing “The Caissons Go Rolling Along” as a group of African-American servicemen were seen off by their girlfriends. The day of the shoot, Scott was shocked to see that the girlfriends had been dressed for the scene in soiled aprons. She argued that no women would bid farewell to their men in such clothing, and backed up her point by walking off the set for three days. She won the argument; the women ultimately wore floral-print dresses instead. But Hollywood mogul Harry Cohn was so angered by Scott’s stand that he vowed she would never appear in another film as long as he lived. After Scott finished work on a movie for which she’d already signed a contract, Cohn’s threat turned into reality. Here’s Hazel Scott, from that scene, playing and singing “The Caissons Go Rolling Along":

Here's another Scott performance, from the 1943 film I Dood It:

Like many other jazz artists during the World War II years, Hazel Scott also made special recordings called V-Discs for military service members. The recordings we’re about to hear put her jazz talent in a solo and then duo spotlight, starting off with “Body and Soul":

As World War II ended in 1945, Scott seemed to be more popular than ever, despite Harry Cohn’s successful blockade against her in Hollywood. Her income was the modern-day equivalent of more than a million dollars a year. Already a star, her profile rose even higher after she married Adam Clayton Powell Jr., a dynamic Harlem minister and civil-rights activist who’d just been elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. As Scott biographer Karen Chilton writes, “They were the most sensational black couple in America. The national press followed their professional lives in feature articles; the black press published cover stories exposing their glamorous lifestyle. All over Manhattan, photographers captured images of them horseback riding, boating, and dashing in and out of their limousine.” That same year, Scott made several sides with noted arranger and conductor Toots Camarata that showcased her in an expansive musical setting. Here’s Hazel Scott and “The Man I Love":

Though Scott would eventually move away from the “jazzing the classics” strand of her repertoire, it remained a part of her next significant studio outing, the 1946 collection Piano Recital. These sides showed Scott’s range of repertoire, including more straightahead renditions of classical pieces, two originals, and an interpretation of “How High The Moon,” which was becoming an improvisatory anthem for the emerging bebop movement. We’ll hear it right after this, one of Scott’s last “swinging-the-classics” renditions on record—Chopin’s “Valse in C Sharp Minor":

Hazel Scott playing “How High The Moon” and Chopin’s “Valse in C Sharp Minor” before that, both recorded in 1946 for the collection Piano Recital, which sold 75,000 copies. That same year Scott gave birth to a son, Adam Clayton Powell III. For the next several years she continued to perform, though she began to eschew nightclubs in favor of concert halls, and to lead a high-profile life with her politician husband. In 1950 she became the first African-American woman to host a TV show, which aired in the New York City area at first on the Dumont network, and then made the leap to national broadcast. The 15-minute program garnered good ratings and relied solely on Scott’s musical performances and conversation. Film historian Donald Bogle wrote of her appearance, “There sat the shimmering Scott at her piano, like an empress on her throne, presenting at every turn a vision of a woman of experience and sophistication.”

Not long after Scott’s TV show began airing in the summer of 1950, a McCarthy-era publication called Red Channels that targeted alleged Communist party members and sympathizers included her in one of its hit pieces. Scott and her husband were outspoken on civil-rights issues, and she had crossed paths and worked with many leftwing figures throughout the 1940s. She was not, however, a Communist, and she decided to voluntarily appear before the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee. Though Scott defended herself vehemently against the Red Channels attack, a week after her Congressional appearance her TV show was canceled.

In the next few years, the height of the so-called blacklist against leftwing performers, Scott was still able to find work, but it did not come as readily as it had before, and she began to frequently travel to Europe in the summer. She also suffered a nervous breakdown at the end of 1951, but recovered to perform a program of George Gershwin’s music at Carnegie Hall with the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra a few months later. In 1953 she recorded a piano trio album for Capitol Records with bassist Red Callender and drummer Lee Young, brother of her good friend Lester Young. But it’s the trio album that she made in 1955 with Charles Mingus and Max Roach, two of the most kinetic instrumentalists to emerge from the bop youth movement of the late 1940s, that helped cement Scott’s legacy as a jazz pianist. Here they are doing “A Foggy Day" and "The Jeep Is Jumpin’”:

Here's Scott with Mingus and Rudy Nichols on drums performing "A Foggy Day" on television:

Throughout the 1950s Scott’s marriage to Adam Clayton Powell II had become increasingly troubled, and the couple began to spend more and more time apart, though they would not formally divorce until 1960. She continued her post-blacklist pattern of summer trips to Europe and also became one of the first African-American performers to appear in Las Vegas. Not long after that she made another piano trio album, which included this take on a Thelonious Monk composition that was turning into a jazz standard:

Hazel Scott performing Thelonious Monk’s “Round Midnight,” the title track from her 1957 album. That same year she moved to Paris, where she would live for ten years, her apartment becoming a salon for other African-American expatriate and traveling artists such as James Baldwin. While there she got a part in a French film; after the first day of shooting concluded, she glanced at a newspaper and saw a headline that Harry Cohn, the Hollywood mogul who had vowed that she’d never make another movie while he was alive, had just died. But her European years presented new difficulties; a second marriage, to a younger Swiss-Italian comedian, was short-lived, and Scott found concert bookings increasingly difficult to come by, relying at times on financial assistance from friend and fellow jazz pianist Mary Lou Williams. In 1967 she moved back to the United States. She appeared in small roles on several daytime TV soap operas, played nightclubs, spent time with her grandchildren, and made some additional jazz recordings. She died of cancer at the age of 61 in 1981; at her funeral service in Harlem, her son Adam Clayton Powell III read this excerpt from a 1950 Langston Hughes poem titled “To Be Somebody” that invoked his mother:

Little girl

Dreaming of a baby grand piano

(Not knowing there’s a Steinway bigger, bigger)

Dreaming of a baby grand to play

That stretches paddle-tailed across the floor,

Not standing upright

Like a bad boy in the corner,

But sending music

Up the stairs and down the stairs

And out the door

To confound even Hazel Scott

Who might be passing!

Oh!

I’ll close with this 1955 television performance from Hazel Scott:

FURTHER LINKS AND NIGHT LIGHTS SHOWS OF INTEREST

*Karen Chilton's biography Hazel Scott: The Pioneering Journey Of A Jazz Pianist From Cafe Society To Hollywood To HUAC

*Eve Goldberg's 19-minute video profile:

*Cafe Society: The Wrong Place For The Right People (Night Lights show)

*Jazz Women Of The 1940s (Night Lights show)

*Cats Who Swing And Sing: Women Singer-Pianists Of The 1940s And 50s (Night Lights show)

MUSIC OUTTAKES: