(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington Indiana, I'm Kayte Young and this is Earth Eats.

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: We've identified that there is a dominate narrative around hunger specifically, and that often it can perpetuate the very conditions of poverty and hunger.

KAYTE YOUNG: This week on our show we examine the stories surrounding hunger and poverty in our communities and how we might in this period of crisis and transition imagine new food systems and address food insecurity with an eye toward social justice. We revisit insightful conversations with Stephanie Solomon and Amanda Nickey with the local community food resource center, Mother Hubbard's Cupboard. Those conversations just ahead so stay with us.

(Gentle piano music)

RENEE REED: Earth Eats is produced from the campus of Indiana University in Bloomington Indiana. We wish to acknowledge and honor the Miami, Delaware, Potawatomi, and Shawnee people on whose ancestral homelands and resources Indiana University was built.

(Music)

KAYTE YOUNG: As a nation we seem to be in transition. We just had a presidential election and so much is in flux due to a raging out of control coronavirus pandemic and we've had a summer of racial reckoning sparked by the brutal killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmed Arbery. Our criminal justice systems are being challenged like never before. And the pandemic brought to light so many flaws in our food system from the long supply chains that cannot easily adapt to crisis to the lack of protections for essential food workers from farm laborers to wait staff. And I've been thinking about conversations I've had with Amanda Nickey and Amanda Solomon of Mother Hubbard's Cupboard, also known as the Hub. A couple of years ago I had them on the show to talk about rethinking emergency food provision which is part of what they do. They are an organization that has been at the forefront of challenging the ways we think about hunger. And I think it's a good time to give these conversations a second listen, now, while many of us are dreaming how we might remake our world.

AMANDA NICKEY: I am Amanda Nickey, the president and CEO of Mother Hubbard's Cupboard.

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: And I'm Stephanie Solomon, the director of education and outreach at Mother Hubbard's Cupboard.

KAYTE YOUNG: Quick update, though Stephanie Solomon was with the hub for more than a decade she is now Prevention Coordinator with the Monroe County Youth Services Bureau and a master's student in the school of public health at Indiana University.

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: We started as a food pantry with a focus on gardening and nutrition and healthy food but when we moved 2013 to our site at West Allen we re-visioned ourselves as a community food resource center. And what we mean that is that we yes have a food pantry, and that is in fact our largest program, but it's housed within a resource center where not only can you come and access food assistance, but you can also learn about crock pot cooking or container gardening or borrow a crock pot or take a container home with you and borrow the tools that you need for your own garden. So that it's not just resources in terms of emergency food, it's resources in terms of what you need to build household food security.

From the very beginning and by design the Hub has been a food pantry that anyone can access in as dignified a way as possible which is not always true when folks are looking to access social services around basic needs.

AMANDA NICKEY: There's no needs testing to use our services, people can come in, there's not really any forms to fill out or proof of identification or income level or need. We run on the honor system. People don't have to come in and jump through more hoops and prove their need in the ways that they might when they're accessing other resources. We trust that if people are coming in and getting food then they need it and it's not our place to judge whether they need it or how long they need it.

KAYTE YOUNG: So I attended the food day event at the Hub this year and reported on it for Earth Eats as you might remember. One of the components of the day involved addressing dominate narratives and I was wondering Stephanie if you could start by talking about what you mean by a dominate narrative.

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: Dominate narratives are really the public narratives that surround us as we navigate the world. So they're narratives about larger issues of poverty, why some people have access to resources and why some people don't. And we've identified that there is a dominate narrative around hunger specifically and that often it can perpetrate the very conditions of poverty and hunger.

So Food Day gave us an opportunity to look at that public narrative and the ways that we as a community conceptualize hunger, why we think it exists, what the solutions are for it. And by tackling that narrative and really uncovering it, we can see where it's truths and lies are and start to rebuild a narrative that's empowering and truly addresses the roots of hunger and poverty.

KAYTE YOUNG: So by narrative, dominate narratives you're really talking about stories. The stories that the powerful stories coming from sort of the mainstream culture, the dominate culture, the culture with power. What are some of the stories that are surrounding food insecurity and hunger relief?

AMANDA NICKEY: One of the narratives around hunger is that it's a temporary thing, that it's something that it's a condition that people experience, or it's situational, it's because of a loss of a job that is temporary. Or something that someone is facing in terms of crisis with their health or some kind of family situation and that the majority of people that experience hunger are able to move out of it. That using services like ours or other emergency food services is just something that people are going to do for a short amount of time.

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: And what follows from that is really... when we talk about stories, is the bootstrap story. There is embedded in that story the idea that we have equal opportunity to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps and truly make the need for a food pantry like ours a temporary occurrence, but we know that that is a flawed story because we see the circumstances that lead to all different needs for food assistance that are often long term.

AMANDA NICKEY: Yeah I would add that the more attractive story that people want to hear is that it's a temporary need, that people come into the pantry, get some services for a couple of months, and then because of their ability to use our food pantry or our tool share or access to our education programming then because of all of that coming together then they are then able to come to kind of work their way out of that need. Work their way out of poverty somehow. And I think that's what less attractive is that that's not the reality, really, for many of our patrons. Many of our patrons have been using emergency food services for years and they will continue to use those services for years to come.

KAYTE YOUNG: So it's not really emergency anymore it's kind of a way of life.

AMANDA NICKEY: It's one part of many resources in our community or beyond that people are using just to survive.

(music)

KAYTE YOUNG: So what are why do you think that it's important to challenge these stories and what kind of impact can that have?

AMANDA NICKEY: I think what's most important in challenging these stories is that it helps us look at solutions from a different perspective. If we think that access to an emergency food pantry and the other kind of programming we have is that those things alone are going to solve hunger in our community then we continue to put resources into those kinds of programs. We continue to support an emergency food pantry or education programs, that kind of thing. But I think if we challenge those ideas and say we have to do more then just this programming, it just changes the way that we approach the problem. And I think that's where our advocacy work comes in, in that we recognize that just these kind of program things that we're doing alone are not going to solve these problems. We have to find ways for people to engage in their larger community for people to get involved in legislation, for people to understand what's happening, the decisions that are being made about their lives and how they're going to impact them.

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: And we cannot advocate around food security with the single narrative and the single story that we have about people in poverty and hunger as it stands. And so part of our advocacy work is starting to lift up the real stories and the lived experiences of people who are needing food assistance, whether it's on a monthly or a longer-term basis. So to ground why dominate narrative is an important topic, we have to look at the problematic stories surrounding hunger and how we can get the true stories out into the world.

(music)

KAYTE YOUNG: One of the things I heard one you mention was something about addressing root causes to hunger. So what are some of those root causes that lead people to need to come to a place like Mother Hubbard's Cupboard to access food?

AMANDA NICKEY: One that's really obvious that I guess that we don't talk about very often is money. People don't not have money because there isn't food to be had, it's because they don't have money to buy it. It's really simplistic, but the solutions to that are really complex. And I think that that's why we don't talk about it. That's why we don't want to think about that when we think about food access or the number of people in our community who are food insecure or that still one in five children in our community don't have access to adequate food on a daily basis. We don't want to think about the fact that it's just a lack of income that's making that happen. A lack of adequate income because solving that problem is so much more complex then hosting a food drive.

KAYTE YOUNG: If you're just joining us here on Earth Eats, my guests are Amanda Nickey and Stephanie Solomon with the community food resource center in Bloomington Indiana. We've been talking about the dominate narratives surrounding hunger in America and what it means to focus on root causes of food insecurity.

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: So if we see hunger as an issue of inadequate food then the best way to address it is obviously through food pantries and food banking and SNAP benefits. But if we look at root causes and we take hunger out of a vacuum and look at it through the lens of poverty and money, then our solutions change. And that's what we're trying to do by redefining the narrative.

AMANDA NICKEY: And I would add that there's always the risk here of sounding like what we're saying is we shouldn't have food pantries, or we shouldn't have food banks or emergency food programs shouldn't exist. And I wanna say that that's not what we're saying. What we are saying is that it's not the sole responsibility of those organizations to solve the problem of hunger. It's impossible for those organizations to solve the problem of hunger. We don't have the power that the greater community has to draw attention to these issues, to provide solutions for these issues, but we're often tasked collectively as emergency food providers to solve this problem, to show how we're improving the lives of our patrons, to show how we're providing opportunities for growth. And I think we have to be honest and say that there's only so much we can do there. STEPHANIE SOLOMON: The narrative that has been successful is that people need to eat now. And we should be proud of the work that our food banks and soup kitchens and food pantries do to address the fact that people need to eat now.

AMANDA NICKEY: And I think it can be challenging to think on an individual level kind of the decisions that we make, or the ways that we live that perpetuate this problem for people in our community. And so when we... I don't know, it can be really uncomfortable to think more deeply about the decisions that you make on a daily basis that allow for economic inequities.

KAYTE YOUNG: Like what?

AMANDA NICKEY: Like development and wages in our community. I don't know. There's a lot of things that we choose to do as a community that it seems like we're not thinking about what's best for everyone. You know a school putting on a food drive around the holidays is not in itself a bad thing, it's a very kind and thoughtful thing. But on a greater scale it's not enough. And how often are we doing these small seemingly caring and well-intentioned things that keep us from addressing greater problems. And that's a really tricky place to be because it's not that those actions in themselves are hurtful or unkind. They're the opposite, they're taking care of people in a moment where they need it. But in some ways it's distracting us from the larger problems and it's keeping us, it's keeping our hands busy with getting food out the door in the day-to-day challenge of just feeding people. And so we don't have as an organization or as a community, we don't have the time and the resources to focus on those bigger problems.

KAYTE YOUNG: So addressing some of those root causes like living wages or affordable housing or the kind of things that might lift people out of poverty so that they don't need to go to a food pantry or don't need to apply for food stamps because they have a sustainable life.

AMANDA NICKEY: Right, I mean we all want to be able to care for our families to the best of our ability and to not have to rely on services or government support. But we have to be honest and say that not everyone has that same opportunity and that's a good place to start.

(music)

KAYTE YOUNG: I'm speaking with Amanda Nickey and Stephanie Solomon about emergency food providers such as food pantries, food banks and soup kitchens. We're discussing ways to move beyond the common stories about hunger in our communities and how to begin to address root causes of poverty. After a short break we'll hear part two of our conversation. In the second part, Solomon and Nickey discuss unicorn stories. You know, the ones about individuals rising up from difficult circumstances to lead successful lives. Inspirational stories like these can end up clouding our understanding and even masking structural inequities that are built into our society. That's just ahead, so stay with us.

(Music)

I'm Kayte Young, this is Earth Eats, and we're continuing our second listen to a conversation with Amanda Nickey and Stephanie Solomon. In the first part of the show we dove into a conversation about the power of stories. We talked about some of the narratives surrounding food insecurity and how those stories and the way we talk about hunger has an impact on how we approach solutions. Our conversation about the power of stories continues and also moves into a discussion about the role of isolation in food insecurity. We'll also take a look at what it means to move from a charity model to a social justice model.

One of the narratives we discuss surrounding food assistance and poverty generally is the bootstrap story, the one that says the American dream is all about equal opportunity. We often hear tales and public speeches for example of the courageous individual beating the odds. They overcame so many obstacles they came from extreme poverty or they came from horrible household and they were able to pull themselves up and be successful.

AMANDA NICKEY: We call those the unicorn stories.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah I mean there's always examples of someone, that are held up.

AMANDA NICKEY: Right and I think, I mean those are the compelling stories. Right? Those are the stories that encourage people to give or encourage people to be engaged in an organization. Those are the stories that we write in the appeal letters that we sent out at the end of the year. But those aren't, it's not the whole story. It's not the story of everyone who comes through the doors at Mother Hubbard's Cupboard. And not every patron has a hopeful story. Not every patron has a story that's going to end well.

KAYTE YOUNG: Those stories though they may be true, they're also still perpetuating that narrative that if this person can then anyone can.

AMANDA NICKEY: And it makes it seem like it's personal failings or poor choices or lack of ambition. Those kinds of things that make it easier to write off someone who didn’t succeed in the way that we thought they should. And we know that it's all complex, it's not black and white. It's not this person made this decision on this day and now they're homeless because of that one decision. It's a lifetime of circumstances and decisions but also lack of choices that lead people to find themselves kind of in the cycle of poverty.

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: I think this discussion of the bootstrap narrative really feeds well into the national discussions that we're having right now about gender and racial inequity and what it would look like to have true diversity and inclusion in our society.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay I'd like to pause here for a brief explanation of the word 'equity'. What is the difference between equality and equity? Sometimes they're used interchangeable, but they are not the same.

My favorite visual for this includes three frames. In the first one we see three kids trying to look over a fence at a baseball game. They're varying sizes and none of them can see over the fence.

In the second frame they're each standing on a crate and the crates are all the same size. Only the tallest kid can see over the fence. That's equality. Each child got the same assistance but since they were starting from different places only the tallest one could reach the goal of seeing over the fence.

In the third frame the tall kid stands on one crate, the middle kid stands on two crates, and the littlest one stands on three crates. They can now all see over the fence. That's equity. Recognizing that we don't all start at the same place, so some need more assistance than others to reach a level playing field. Okay back to Stephanie Solomon.

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: If we're working from the assumption that we are an equitable society then the burden falls on the individual when they can't for example afford food. But if we're working from the understanding that the story is much more complex than that, then we can see that they're many opportunities that are being lost because of systemic issues that we have. And again if we take that holistic look at those issues we can really reframe and find some opportunities for true food security in our communities but also in our larger culture.

KAYTE YOUNG: So one of the things that I have seen come up in your work is the idea of moving from a charity model to a social justice model. And I was just wondering if you could talk a little bit about what that means to you to move from a charity model, what's wrong with charity, and shouldn't we all be charitable?

AMANDA NICKEY: So I think this goes back to that idea that kind acts in themselves are good. Right? That charity is good. We can say that right up front. But if you want to see something change, if you want there to be an improvement, if you want the situation that for that individual requires a charitable act to improve then you have to bring in this idea of social justice. You have to think about, does this person have the opportunities or the support that they need in order to be successful in what it is that they're trying to be successful in. If it's just being able to make ends meet or take care of their family or go to school or further their education or whatever. It's important to look at what are the structures that are in place that are keeping them from doing that, what are the obstacles that are in their way. And charity alone isn't going to solve that problem. It might solve that problem for that one person but it's not gonna solve the problem for the next person.

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: Often there's a patronizing air behind charity. It's very much in the narrative of us and them, we are the givers, and they are the receivers. And like Amanda said, charity is not a bad thing. Giving and receiving is natural and necessary, but we want to be the kind of organization where we are all one. Those of us that are putting the food on the shelves and those of us receiving the food from the shelves, all of us together are working for a more just community. And that's how I see a true transition from a charity to a justice model. It's breaking down those walls and saying how can we all work together for the kind of community that we all want to work in? Instead of us telling folks "This is what you need and this what your community should look like"

KAYTE YOUNG: So I saw on the wall at Mother Hubbard's Cupboard "Food is a basic human right" What do you mean by that?

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: We mean by that just what it sounds like, that everybody deserves access to the food that they need. So just like water, clean water is a basic human right, food is also a human right. We would not be able to live and sustain our bodies without food.

AMANDA NICKEY: I think it's also important to think about it in terms of access to food as a basic human right, because when the focus is on access what that means is that we have to do something. If we're talking about creating access to food for everyone, that everyone should have equal access, it requires that we focus on structures. And we assess what are the obstacles. If we're just talking about food as a basic human right it takes the responsibility away from the larger community to do something about that.

KAYTE YOUNG: Or to do something other than hand someone some food.

AMANDA NICKEY: Exactly. It means that we have a social structure, an economic structure that supports that everyone can take care of themselves.

KAYTE YOUNG: So the difference there is taking care of themselves rather than having to rely on a charity or on a social service.

AMANDA NICKEY: Yeah exactly.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah.

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: That makes me think about how in our mission we talk about dignity and self-sufficiency, and if you take that kind of at a surface level and talk about self-sufficiency as an insular thing, as an individual or family building their own self sufficiency that's kind of missing the larger point which is that self-sufficiency is achieved when we build networks in our community. Self-sufficiency is possible when we have a village to rely on. It's not just about providing food and education around cooking and gardening it's also about breaking the social isolation of those experiencing poverty and hunger and building a village of networks for folks to rely on each other.

KAYTE YOUNG: And that really does increase your food security the more resources you have, the more people that you know, the more connections that you have. I mean when you think about something just as simple as dinner tonight, I ran out of groceries, it's the end of the month, I don't have a paycheck. But if you invite me over to your house or if I'm your neighbor and I can like stop in, that's already increasing my food security just having that connection. So I can see where experiencing poverty and also being isolated in your community, not having those connections, could really in a tangible way affect your access to food and other resources.

AMANDA NICKEY: Yeah I mean I think back on when I was a kid, and my mother was very close to all of our neighbors and if we needed something we knew that we could go to a neighbor and ask. And as a kid I didn't think about the fact that maybe the reason we were asking the neighbor was because we couldn't afford it ourselves. I just knew that if we needed something we could ask the people that lived around us, the people that we were close to. And I think that a lot of people are missing that, Especially in low-income communities. But something that came out of some research that a doctoral student did for us a few years ago, they surveyed people in a low-income community and found that those people who knew their neighbors and felt connected to their neighbors, reported feeling less food insecurity. They felt like they could rely on neighbors for support when they needed it. And it's an obvious thing that we probably know but I think it's great that there's some research to back that up especially in our own community.

KAYTE YOUNG: I asked Nickey and Solomon about the difficulties in moving towards a social justice model while still serving as a food provider in the community. I asked about some of the risks and complications involved in bringing forward the problems inherent in providing direct food aid. We talked about the risk of alienating some of the supporters of the organization and about how at least in this moment it's not an either-or situation.

AMANDA NICKEY: It would be naive to think that we could shut the pantry down tomorrow. And not only naive it would be cruel. For better or for worst we have this position in the community and we're providing groceries for thousands of people a week, we can't step away from that. But it doesn’t' mean that we can't focus on other things and try to build power in other ways and try to listen to people who aren't often being listened to or to kind of raise up those stories of patrons that aren't being heard otherwise. We can do both.

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: As somebody who worked at the food bank then moved to Mother Hubbard's in my current role there's a very strong narrative in the food bank about the work that's being done. And just like any other story it has its truths but it's also it has it's holes too. And so in some ways...

KAYTE YOUNG: What is that narrative?

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: Well the narrative is the one that we talked about earlier, which is that people need to eat food today. People need food on their plates today. And so we are doing the good work of making sure that everybody has the food that they need. And so if that's our narrative that that's our role is, and that anything else that we do is mission creep, then it's gonna be pretty uncomfortable to sit down and have people say, "Let's look at the ways that the system reinforces systems of oppression." So it's inevitably gonna be uncomfortable to change that narrative. But I think there's a lot of people that are ready to do the work.

KAYTE YOUNG: So by mission creep you just mean where you're getting off... your mission is to feed people, don't expand it beyond that.

STEPHANIE SOLOMON: I read about mission creep in Andy Fisher's book Big Hunger, where he discusses the challenges that food banks and other emergency food providers have in taking on issues outside of hunger related policies. So for example he talks about that they might have an advocacy wing as part of a food bank, but the advocacy wing is pretty constrained in terms of talking about issues like SNAP or food stamps and child nutrition reauthorization. Whereas if the city that the food bank is in has a living wages campaign it's often seen by the food bank to be mission creep to get involved, even though living wages would do a lot for people experiencing hunger and needing their services.

In the world of anti-hunger, if your mission is to get food on people's plates it can feel like mission creep if you're looking at roofs of hunger like poverty and injustice. So we have to look outside of the vacuum of hunger for it to even make sense to be looking at these bigger issues.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: I've been speaking with Amanda Nickey and Stephanie Solomon of Mother Hubbard's Cupboard or the Hub in Bloomington Indiana. The Hub is a community food resource center offering food pantry services, education around growing and cooking food, and an advocacy program focused on equity and social justice.

Since this conversation first aired, Stephanie Solomon has moved from the Hub to a position as the Prevention Coordinator at the Monroe County Youth Services Bureau. I spoke with Amanda Nickey earlier this year in March about the challenges the Hub is facing due to the coronavirus pandemic. We'll hear that conversation after a short break so stay with us.

(Music)

(Music)

(Music)

In March of this year when the coronavirus hit the U.S. and stay at home orders were issued, the Hub had to switch gears quickly. Closing down wasn't an option. Food is an essential service and with many people suddenly out of work, they knew their services would be more important than ever. I visited the Hub in those early days of the pandemic and spoke with president and CEO Amanda Nickey. For those of you just joining us, Amanda Nickey will reintroduce Mother Hubbard's Cupboard.

AMANDA NICKEY: We offer a food pantry that operates kind of like a grocery store. We try to offer as much fresh food as possible. People can just walk through the pantry and pick the items that they want. And then we also offer education programming, so we have cooking and gardening programming, a tool share that is a lending library of cooking and gardening tools. We have kids programming, kids cook and kids gardening workshops, and then we also do advocacy around local, state, and national issues affecting hunger and poverty.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: Do you consider the work that you do at Mother Hubbard's to be an essential service? Like as this is kind of coming up right now during this crisis there is a lot of talk now about what are the essential services. Do you consider this an essential service?

AMANDA NICKEY: Yeah, I mean I think, simply because folks rely on us week to week just to make it we have become an essential service. I think one of the things that's like slowly hit me over the last week is how unprepared most people are for a crisis like this. It's not like responding to a natural disaster, where the harm or the risk has happened, or you know the disaster has happened and now you’re going into a community and trying to meet the food needs. You know food banks have lots of experience with that kind of thing but when I think about what we're all going through right now like, we're all at risk all the time. And that's something that I’m trying to wrap my brain around.

How do we as emergency food providers respond to the everyday need, the crisis needs, and the real risk to ourselves, and to others that we're interacting with. I know that everyone is saying this, it's unprecedented, but it is. And that's the thing that I don't really know what to do. And I you know, right now, today we are an essential service. Unless someone else or someone from the government or the military or something steps in and takes control over this, then we are an essential service.

KAYTE YOUNG: What do you think that this crisis tells us or can tell us about how we deal with hunger in the U.S.?

AMANDA NICKEY: I mean I think mostly that it's highlighting how much of our everyday lives food banks, and food pantries and soup kitchens have become. That when someone needs food then these are the ways that they should go about getting it, instead of really trying to address those root causes, and that it's an inadequate response, and that the people who rely on our services and people all over the country who rely on similar services just to make it through the week, that these are the people that are gonna be at a higher risk of contracting the virus and getting seriously ill because they have to be out there. They have to get food wherever they can during the week from as many resources as are available to them. They don’t have the option of going to the store and buying several weeks’ worth of food or ordering things online and having it delivered to their home. I just I think that it's highlighting all of the different ways that we actually have a different food system for people who are experiencing poverty.

KAYTE YOUNG: Do you think it's the responsibility of charities like a food pantry to meet this need?

AMANDA NICKEY: I think that's a difficult question because I think that the community as a whole, feels that it's our role to meet the need during this crisis. Right? But I have to feel a little bit like, at least for me, I don’t' feel fully equipped to deal with this crisis and to do the work that we are supposed to do. We're really good at running the organization that we have, but this is something that we've never ever had to experience. And I think that we're being careful, and we're taking precautions, and I know that all the other organizations in our community are doing the same thing, and we're all doing the best that we can with what we have. But it feels... I don't know it feels a little bit lonely. It feels a little bit like we're just making it up as we go and hoping that we're doing the right thing.

So, I mean is it a responsibility, is it an obligation, is it our role, I think those are a little bit different things. I know that all of... I'm speaking for the Hub, but probably other organizations in town too, like we do feel like if we don't do this, who’s going to? But we feel like that everyday anyway because that's just the reality of the work that we do. That if we don’t provide food for people who need it in our community, who else is going to do that? Wages aren't going up, housing isn't getting cheaper. The people who have power to change the conditions in our community aren't doing that, and so we have to be here every day, doing the things that we do. And now in this crisis that at least I don't feel fully equipped to handle, we have to keep doing that, and we have to do more, and we have to take on more of a risk, more of a risk than we've ever had to do before.

(Piano music)

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: The first change that they made was to cancel all programming except for food distribution.

AMANDA NICKEY: We stopped all of our non-essential programming. So, workshops and all of our cooking demos, the drop-in classes that we have, kids cook, all of our kids programming. We suspended the tool share, rentals, right now. Mostly we just don't have the capacity to deal with the tool share program on top of everything else.

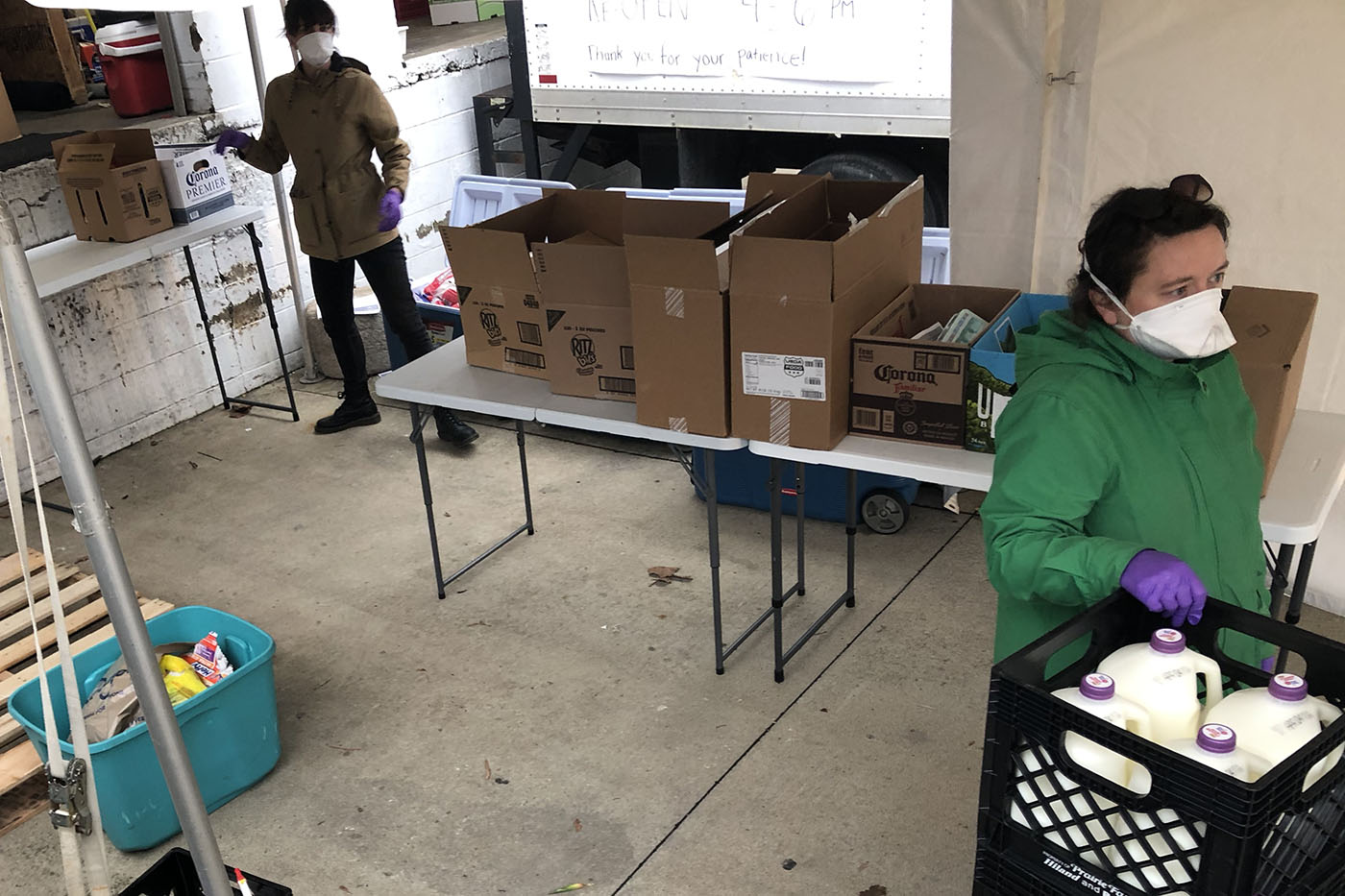

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Then they limited the number of people allowed in the pantry at one time. Quickly they switched to a pickup system outside on the patio and asked people to approach one at a time.

AMANDA NICKEY: And we set up some cone barriers that just said, "Stop here, one household at a time." And asked people to just walk up, tell us if they wanted, what kind of meat they wanted. There were some options that people could choose from. We prep the box; we take it to a table that's 6 feet from the cones. When we walk away after dropping the box down, then we would tell folks they could come up and pick up their box.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: On Monday, March 16th, they made the difficult decision to prohibit volunteers on site.

AMANDA NICKEY: We have anywhere between 4 and 500 volunteers on an annual basis, and dozens each day on different shifts, and it's just too many people to try to catch up to speed every day. And we wanted to make our best effort to close our circle and limit the number of people that we're in close contact with, and it just seemed like the best thing to do, is to minimize who was gonna be in the building and who was going to be packing the boxes and who was going to be in close quarters together.

So, we narrowed it down to just staff, and it feels terrible. And I know that you know, this is the kind of situation that people want to do. They wanna take some kind of action. And I know it's so hard for so many people to know that the best action they can do, is to stay at home. It was heartbreaking to have to tell so many of our regular volunteers last week that, "We love you and we wish you could be here, but you can't. The best thing you can do for us is to stay home. And to support us from afar."

I do want to talk about the community response, because we've seen a lot of support from the community and I think a lot of organizations in town have, and I’m sure organizations all over the country have. But we've seen an amazing outpouring of support either financially or with resources. We desperately needed boxes last week and we were getting box deliveries all day every day from folks in the community. We've had a lot of financial donations that are really really helpful right now. Other businesses in town who have dropped off supplies for us, gloves or boxes, food, beer (laughs) those kinds of things. Just to help us kind of get through each day. Has been really it's been really moving for me, sometimes this work can seem really lonely, and sometimes it feels like people in the community don’t really understand how serious the situation is every day, and so for people to come out and show us this kind of support right now it means a lot. Even just the email messages or the voicemail messages that we're getting from folks that are saying, "Thank you" or the posts on Facebook that are just saying, "Thank you for being there" or "Thank you for doing this" or you know "Keep at it, you’re doing a great job." It's helping us. It’s helping us get through each day.

(in background: "Thank you!")

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: So, they were down to six staff members, focused on a new system of packing up food boxes and handing them out in the parking lot. I stopped by on Friday in keeping my distance, I observed their system for the last two hours of the day. The staff arranged stools and rope in the parking lot with signage directing people to the tent. The lot could hold about six cars at once. It was full for the entire two hours with cars backed up down the street. A few folk without cars walked up and stepped into the line. Each household could take the number of boxes that they needed and had a choice between fish and chicken and an option for a gallon of milk.

AMANDA NICKEY: It's an incredibly different model than what we're used to.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Full disclosure, I worked at the hub for seven years. Central to the organization's mission is serving people with dignity, offering choice, and building relationships. Handing someone a prepackaged box wearing a face mask and gloves, and keeping a six-foot distance, goes against everything the Hub stands for.

Amanda, Sara, Liz, Kristen, Hannah and Alissa, managed to keep their spirits up, cracking jokes, cranking the music from the warehouse. At one point when a patron had trouble hearing the meat choices, Amanda resorted to gesturing. "Fish?", moving her hand like a wave, then, "Chicken?", with thumbs in her armpits she flapped her arms like chicken wings.

AMANDA NICKEY: Fish or chicken? Do you need fish or chicken? (laughter)

KAYTE YOUNG: [NARRATING] It was impossible not to laugh out loud or at least crack a smile.

AMANDA NICKEY: [To patron] Okay, there you go. Thanks!

PATRON: Thanks guys, for everything. Thanks for your work.

AMANDA NICKEY: Stay safe!

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: And I observed another gesture from Amanda. After the boxes for a household were gathered on the table and ready for pickup, Amanda would let them know "Here you go, thanks" and she'd go give the sides of the boxes several affectionate pats with her gloved hands before walking back to her station to maintain that six-foot distance.

AMANDA NICKEY: Here you go (pat pat)

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: I read those pats as her intention to connect, almost a virtual hug. A way to say, "I can’t be close to you, but I care about you."

AMANDA NICKEY: We need one or two boxes. Do you want milk?

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: There wasn't a lot of room for such tenderness in these interactions. For the sake of clarity, it was mostly reduced to instructions and requests, often yelled across the distance and over the hum of idling cars. But Amanda found a way.

AMANDA NICKEY: Do you need one or two boxes? Then come over here. Fish or chicken?

PATRON: What?

AMANDA NICKEY: Fish or chicken?

PATRON: Chicken.

AMANDA NICKEY: Do you want milk?

PATRON: Yes please.

KAYTE YOUNG: It seems like that's what people are doing all over in our communities adjusting to this new normal, finding a way.

(Piano music)

The Hub continues to distribute food from their parking lot. They've experienced a significant increase in households served since starting their COVID response. You can read a statement composed by the Hub staff in response to a letter that the Trump administration had attached to federal food aid boxes just ahead of the election. Like many other food banks and food pantries, the Hub staff removed the letters before handing out the boxes to avoid connecting food assistance to partisan campaigning. We'll have a link to their website at Earth Eats dot org.

I hope these conversations have provided food for thought and that they can serve as a launching pad as we continue to dream and to plan and to reimagine our food systems. We may be entering an era of new possibilities for producing, processing, distributing, serving and sharing food in our communities. Perhaps we can approach this reimagining through a lens of social justice.

(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

KAYTE YOUNG: I'm Kayte Young, and that's our show. Thanks for listening, take care.

RENEE REED: The Earth Eats team includes Eobon Binder, Mark Chilla, Abraham Hill, Josephine McRobbie, The IU Food Institute, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week to Stephanie Solomon, Amanda Nickey and everyone at the Hub.

RENEE REED: Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from the artist at Universal Productions Music. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey.