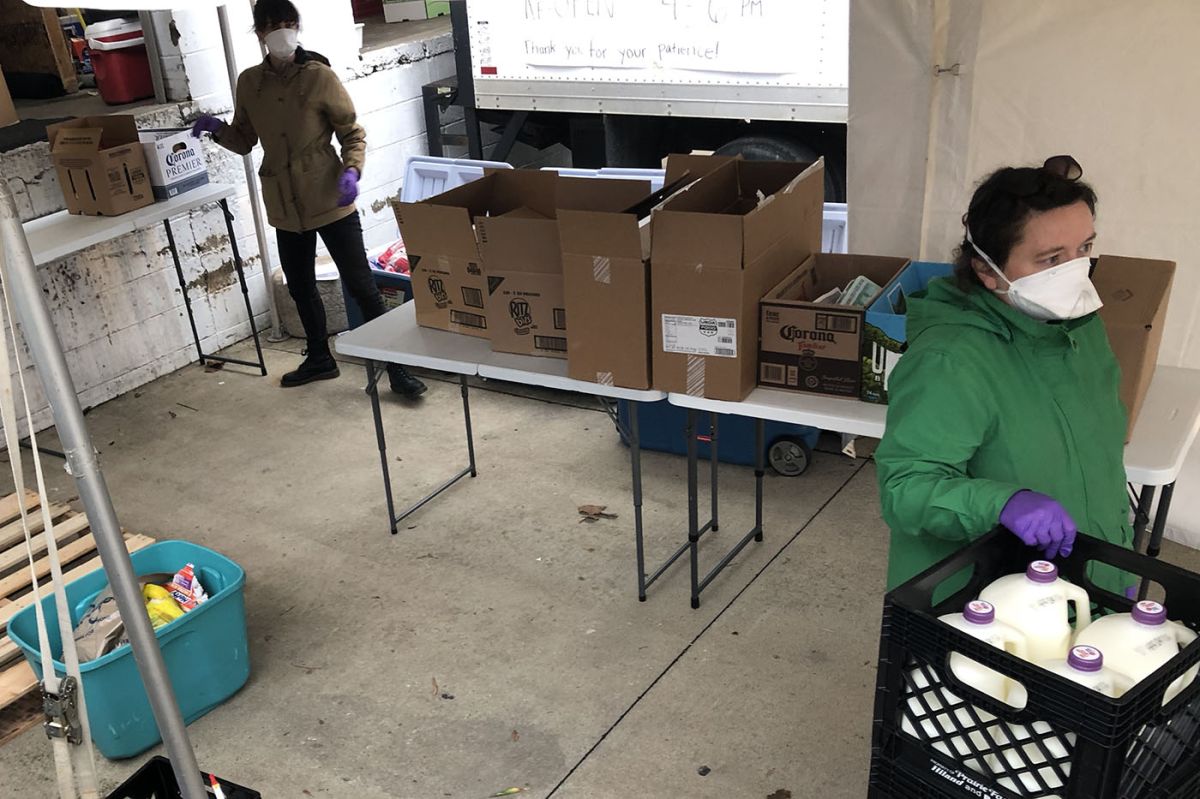

Sarah Cahillane reaches for a box of food from the truck bay while Amanda Nickey asks (from a distance) if a food pantry patron wants milk in their box. (Kayte Young)

"One of the things that slowly hit me over the last week, is how unprepared most people are for this kind of crisis."

This week we give a second listen to a conversation with Amanda Nickey, President and CEO of Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard, a local food pantry making adjustments to continue to get food to the people who need it most.

Food is essential

While restaurants and cafes around the country closed or moved to takeout and delivery in response to Covid 19 restrictions, the grocery stores remained open. Truck drivers were allowed to stay on the road longer to keep food on the shelves. And migrant farm workers continued to plant, tend and harvest crops in the field.

And in Bloomington Indiana, the Hoosier Hills Food Bank is still running, supplying organizations like the Community Kitchen, Shalom Center and Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard with food for those in our community who struggle to get food on the table in the best of times, let alone in the middle of a pandemic.

But even these essential service providers have made dramatic changes to the way they operate.

In March of 2020, I spoke with Amanda Nickey president and CEO of Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard, known locally as The Hub, a community food resource center in Bloomington Indiana

The first change they made was to cancel all programing except for food distribution. Next, they limited the number of people allowed in the pantry at once.

Quickly they switched to a pickup system outside on the patio, and asked people to approach one at a time. On Monday, March 16th, they made the difficult decision to suspend all of their volunteer shifts.

So, they were down to 6 staff members focused on a new system of packing up food boxes and handing them out in the parking lot. They set up a few pop-up tents to protect them from the rain, but they leaked. By the end of the week they had rented an event tent from Master Rental, and had their system down pat.

I stopped by during those first weeks to observe their routine for the last two hours of the day.

Inside the pantry's warehouse, staff members sorted food and packed up boxes of dry goods and produce. They passed the boxes to Sarah Cahillane and Amanda Nickey, in masks and gloves, in the truck bay under the tent.

As people drove up, they'd park their cars and step up to a set of cones, placed 6 feet away from a plastic table. Amanda would ask how many boxes they wanted, if they wanted fish or chicken and if they wanted milk.

She and Sarah would add the meat and milk to the boxes and Amanda would carry the boxes to the table. Then she would walk back 6 feet while the patron picked up the boxes and took them to the car.

It went on like this for hours. 4 hours each day, even in the pouring rain.

In our interview, Amanda talks about the expectations for emergency food providers in a pandemic (and every day) and she reflects on what this crisis reveals about how we deal with hunger and poverty in the US.