KAYTE YOUNG: Production support for Earth eats comes from:

Bill Brown at Griffy Creek Studio, architectural design and consulting for residential, commercial and community projects. Sustainable, energy positive and resilient design for a rapidly changing world. Bill at GriffyCreek.studio.

And Insurance agent Dan Williamson of Bill Resch Insurance. Offering comprehensive home, auto, business and life coverage, in affiliation with Pekin Insurance. Beyond the expected. More at BillReschInsurance.com

(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

From WFIU in Bloomington Indiana, I'm Kayte Young and this is Earth Eats.

SUZANNE BABB: You can't talk about food access without talking about a living wage. You can't talk about food access without talking about affordable housing. (You) can't talk about food access without talking about affordable healthcare. Like how many people have gone bankrupt because of health emergencies is just astounding to me.

KAYTE YOUNG: Our guest this week Suzanne Babb examines issues of food security within a broader context of other social issues we face. And talks about the way forward towards a more equitable food system. That conversation is just ahead so stay with us.

Renee Reed is here with our news. Welcome back Renee.

RENEE REED: Hi Kayte. It's great to be back.

The end of summer has intensified debate and concern about the reopening of schools this fall as districts grapple with safety and logistics puzzles, including how to deliver school meals to students in need. The move to distribute meals by delivery or pickup has come with the push to relax nutrition standards set up under the Obama administration. In a new study Harvard researchers found that the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 had a significant effect on child obesity for kids who face higher risk due to poverty. The program boosted nutrition standards for meals and beverages provided through the national school lunch breakfast and smart snacks program.

Over the past few years the Trump administration tried to roll back key provisions of that law such as whole grain requirements and reduced sodium limits. But a federal court struck down that move. The study linked the standards with the 47% decline in obesity in 2018 compared to what would have been expected without the changes among children living in poverty. Before the changes took place the risk of obesity in the highest risk population had been climbing steeply each year. But after the law took effect, rates started declining annually.

Lead author Erica Kenney assistant professor of public health nutrition in the Departments of Nutrition and Social and Behavioral Sciences said improvements in school lunch nutrition are helping to protect the health of children from low-income families that rely on school meals.

Missouri and Oklahoma are both using federal dollars earmarked for coronavirus expenses to help the meatpacking industry. Grants will go to meatpackers in both states to pay for protective equipment and plant upgrades that can increase capacity and improve safety. Missouri Agriculture director Chris Chenn says coronavirus showed a need for a better meat supply chain.

CHRISS CHINN: During COVID-19 our food supply was tested from farm to fork. Farmers and ranchers saw high livestock supplies on their farms while consumers saw their choices of certain cuts of meat shrink or go away.

RENEE REED: Both states have limits on grants available to anyone meat processor and have rules they say are designed to target the money to small companies. Thanks to Chad Bouchard and Harvest Public Media's Jonathan Ahl for those reports. For Earth Eats news, I'm Renee Reed.

(Earth Eats news theme)

(Trendy music)

KAYTE YOUNG: As early as the first week of stay-at-home orders in March, we saw images in the media of absurdly long lines of cars filled with families seeking food assistance. From San Antonio Texas to Burlington Vermont, food banks were stepping up to get food to those who faced sudden unemployment. In some places the National Guard was deployed to assist with moving food, packing boxes of canned goods, and directing traffic at distribution sites as many nonprofits faced increased demand and reduced volunteer crews.

It can be heartening to see resources popup as they're needed to address food insecurity in our communities, just like it can be heartening to participate in a food drive. But my guest today challenges us to think beyond charity models when we look to address food insecurity.

SUZANNE BABB: My name is Suzanne Babb, I worked at a nonprofit called WhyHunger, and I codirect the U.S. programs there, and I'm also a farmer at a Black and Latinx women lead farm called La Finca del Sur, and I'm a founding member of an organization called Black Urban Growers.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: WhyHunger supports grassroots community-based organizations in creating a more just food system.

SUZANNE BABB: And so we both work in the U.S. and around the world, and we work with everything from emergency food providers to peasant lead social movement. And we provide sometimes it's financial support, sometimes it's technical systems, but it's all grounded in building relationships with the organizations and networks that we're part of. And we're supporting them through years of relationship and being the incompetent with them through everything that they're going through, and that helps to build trust for them so that they can come to us for things that they might not go to another kind of support or funding organization for. Because the whole basis of any... of organizing for anything is about relationships.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: I spoke with Suzanne recently in a zoom call and asked her about this moment; from the COVID9 pandemic to the national reckoning around race, and the connection between these events and what they're revealing in terms of food access and food assistance.

SUZANNE BABB: I think COVID has been bringing to light those connections, in the way that racism plays a role in the food system. I think from the start of the U.S. racism has been part of the foundation and I think racism is a tool that capitalism uses to continue to exploit people for their labor.

And if we're looking just at the food system, you know we can take it all the way back, or we have to take it all the way back to when Europeans came here and tried to get rid of indigenous people and move them off their land. And land is the basis of freedom and it's the basis of cultivating food. And people had beautiful food forests and systems in different ways, whether they were hunter gatherers or whether they grew food. And so that was like the first initial move in terms of food system.

And then if we think about slavery where Africans from West Africa were kidnapped and brought over here to work in agriculture, partly because they were so skilled at it. But treated inhumanely, like property, and built the wealth of the country through growing cotton and tobacco and sugar that got shipped throughout the U.S. and throughout the world. That's our food system, right?

But I think always in talking about this we have to talk about the oppression. We have to talk about the liberatory parts of the food system, cause that's always gone in conjunction.

So just thinking about... as a black woman, as a black farmer it's been really important to reclaim those liberatory parts of history and thinking about how my ancestors brought seeds over in their hair. Like that was the one thing that they could bring, and it just talks about how important food is, how important food is to culture. Not only to consume is nourishing for us, but tied to spirituality, tied to language and tradition. And even stories of like when folks in place still trying to ask for a piece of land to grow their own food. And that's why things like watermelon and okra and sweet potatoes still exist and are still part of black cultural foods because they came from Africa and that was part of the culture that we can still continue to have.

But I think that in the food system there has been this history of always using another group of people, another racialized group of people for the labor. And then within to justify that exploitative labor, using people for their labor, comes the stereotypes and the belief that these people are inferior, and that white people are superior. And that's... regardless of what system you look at, that's kind of like racism is used as a tool to justify that. And if we're just looking at the labor from farmers, farmers of color who had less access to credit and capital for their farms, less access to markets intentionally, to food chain workers who are usually people of color because... you know other people don't want to do that, and they don't get paid as much, or even if they are white people, the white people get paid more than the food chain workers. Work in inhumane conditions that are not safe, that are exposed to pesticides. To consumers, to communities of color that are denied access.

And that access is not... you know it's not by chance, it started back in the time when the government was giving people loans to buy homes in the suburbs. And cities used to be a little more diversified in terms of their demographics. And so when white people moved out to the suburbs, the businesses moved with them. And banks decided to divest from these city neighborhoods, that's where redlining comes from. Redlining, like they actually took the red line and (the banks) said, "We're not gonna invest, we're not gonna invest in businesses, small businesses to go in there, we're not gonna give people to buy houses." All of that thing. So you create a vacuum where people don't have access to food. And it was deliberately communities of color. So racism plays... that's why people use like "food apartheid" versus "food desert" because that speaks to intentional policies and practices that have denied people access to healthy food.

And I think that then wrapped around what's happening right now with COVID-19 is where... because people had access to unhealthy food that was intentionally put in this neighborhood that they didn't have control over, they have a higher rate of diabetes, and high blood pressure, and kidney disease and all of these things that now make them more susceptible to having COVID-19 in a much more severe form. So it's like... it's almost like circular in this.

And that's why... like food has to be at the center of these kinds of conversations around this. Because food is the reason why people are sick and are more susceptible to this virus. And people need their food during this time. And people who are not treated well, are not paid well, and are not kept safe, they still have to go out and make sure that everybody else gets the food that they need.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Suzanne talked about organizations on the ground within communities, taking up these current food access challenges by forming mutual aid groups, setting up bartering systems and finding alternative ways for people to get what they need.

SUZANNE BABB: I know like in the Bronx our community garden along with other gardens and farms in the Bronx and the south Bronx are getting together to create a food hub. Which has always been a conversation but feels even more pertinent now. So it's like how can we grow food and like aggregate it together and maybe work with some rural farmers who can bring food in and have people have access to like good food boxes, that's been aggregated from all these community gardens and farms. Which we've always wanted and now this pandemic has accelerated and amplified the need for that.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Suzanne notes that it matters who is creating these solutions.

SUZANNE BABB: It is led by and the solution comes from people in that neighborhood, the people who are most impacted. Which is really important, cause often these solutions come from outside and are not in conversation with people in the communities about what they need.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: As someone whose been working in the emergency food system, I wanted to hear Suzanne's reaction to the images of people in cars, lined up, waiting for hours and hours for boxes of food as the pandemic restrictions closed down so many businesses.

SUZANNE BABB: It is not surprising to me to see that, when you know that a lot of people are one emergency away from needing that kind of help. The Poor People's campaign who we're a partner of, talks about how most people don't have $400 for an emergency or if they have to pay $400 that's going to push them further into poverty. And just to think about the millions of people that have lost their jobs.

And I think about the strain that puts on emergency food providers, on food pantries, food banks, soup kitchens. Who before the pandemic were looked at as the solution to hunger, and that is... and they are not the solution.

And I think in the network that we're a part of, so in the Hunger Gap that's one of the things we have been vocal. Nonprofits are not the solution to food security. It is really the government's role and they have really... they've removed themselves from that responsibility. We do have food stamps, people often don't get enough of it, but there needs to be a bigger kind of food security plan in the United States to protect people. Because food is a human right and there are covenants that the U.N. has created, and other countries have worked on policies and we really need it here in the U.S.

But I think also what's come up for me is that the response to this has been again charitable. You know, like tons of money going towards Feeding America for food banks... just so that they can further institutionalize food banking as the solution. But that's not the answer.

But what has been really great has been in conversations that I've had with everyone from food sovereignty and food justice, to emergency food organizations, is this realization that in order to be more resilient we need to work on local food economies. And what that looks like might be different for everybody and every community but that we cannot rely on this national and global food system to take care of people all the time, but especially during times of emergency because of so many faults within it, because it's so delicate. That was one of the big issues again with the pandemic was what's going to happen to the food supply chain. A meat processing plant that serves half of the country has an outbreak and then all of the sudden there's no supply.

And not only do local food economies make us more resilient, but it allows more people to be a part of the food system in an equitable way. It allows local small scale independent farmers to participate and gain access to markets. It allows people to maybe grow their own food. They can go, they have more options in terms of what they can access, and it also makes you think about what are alternatives to say a grocery store. Like coops and farmers markets and the roles that they can play. Because farmers' markets for a lot of people seem safer now because they're outdoors versus grocery stores. Or a lot of places don't have access or 70 miles away from the nearest grocery store. So there needs to be more options and those options need to be grounded in equity and justice so that everyone has an opportunity to participate in it in some way.

KAYTE YOUNG: I'm speaking with Suzanne Babb of Why Hunger. More from our conversation after a short break.

(Earth Eats production support music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey) Production support comes from:

Bloomingfoods Coop Market, providing local residents with locally sourced food since 1976. Owned by over 12,000 residents in Monroe County and beyond. More at Bloomingfoods.Coop.

And Elizabeth Ruh, Enrolled Agent with personal financial services. Assisting businesses and individuals with tax preparation and planning for over 15 years. More at PersonalFinancialServices.net

And Bill Brown at Griffy Creek Studio, architectural design and consulting for residential, commercial and community projects. Sustainable, energy positive and resilient design for a rapidly changing world. Bill at GriffyCreek.studio.

(Music)

This is Earth Eats, I'm Kayte Young, and my guest today is food justice organizer and urban farmer Suzanne Babb. We were talking about the kind of responses we need to see in our food system that go beyond distributing food boxes in a crisis. I suggested that it seems like a failure of imagination that we can't see our way to a different response to food insecurity other than food banks and charitable models.

SUZANNE BABB: I think you're totally right it is about a failure of imagination and I think also like we buy into it. Food banking has been around probably 30-40 years now and so people have just gotten used to somebody comes around, whether it's the boy scouts or the girl scouts. And then you get your can of food. And just some people need this help.

But there are so many things that are part of that narrative that need to be examined. Like why do we have to do this? Why do some people need this food? Why do we have food banks as a solution? And investigate the kind of dominate narrative we have around hunger. Oh you know just some people aren't working as hard and they need to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, when that image and that concept doesn't even make sense. You cannot literally pull yourself up by your bootstraps. You can pull your boots up. (Laughs)

KAYTE YOUNG: You can pull your boots up (laughs)

SUZANNE BABB: But you're in it you can't pull those up, like... so I think that that's what it requires. And I think you know, those conversations now are happening and at the same time with the protests around police violence, we're talking about defunding police.

Those things throw people for a loop because they cannot imagine that something else is possible. Something has been possible for a lot of other people so let's just, let's just be open to possibilities. Let's be open to the idea that like if you give people a living wage and they have affordable housing and affordable healthcare, and you give them access to grocery stores with like fresh healthy food or farmers' markets, or the tools to grow their own food, that another way is possible that they don't need food banks. Or the government makes sure that we have access to capital to make all of these things happen, we don't need that.

You know same thing with defunding the police, if communities have what they need so that their crimes of poverty are not being committed, so people feel safe when they have adequate lighting and green space and all these things that make their neighborhood and their lives less stressful, maybe we don't need to police them in that same way.

KAYTE YOUNG: We talked about people who worked in the food system, either as farm labor or as factory labor, grocery store workers and the food service industry. In the pandemic they've been deemed essential workers, but their pay and status does not reflect that.

SUZANNE BABB: 25% of the people in the country worked in food and it's one of the lowest paying jobs. And so I think it's like you can't talk about food access without talking about a living wage. (You) can't talk about food access without talking about affordable housing. We can't talk about food access without talking about affordable healthcare. Like how many people have gone bankrupt because of a health emergencies is just astounding to me. And people having to make a choice between rent and food? And that is food chain workers, that's other consumers and that's farmers as well.

So I think that this work requires a lot more kind of collaboration with other folks who are working on other things, and even within the food system, working on things together to kind of push back the system that already exists.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: In her role with Why Hunger, Suzanne is involved in the network called Closing The Hunger Gap. I asked her to talk about their work.

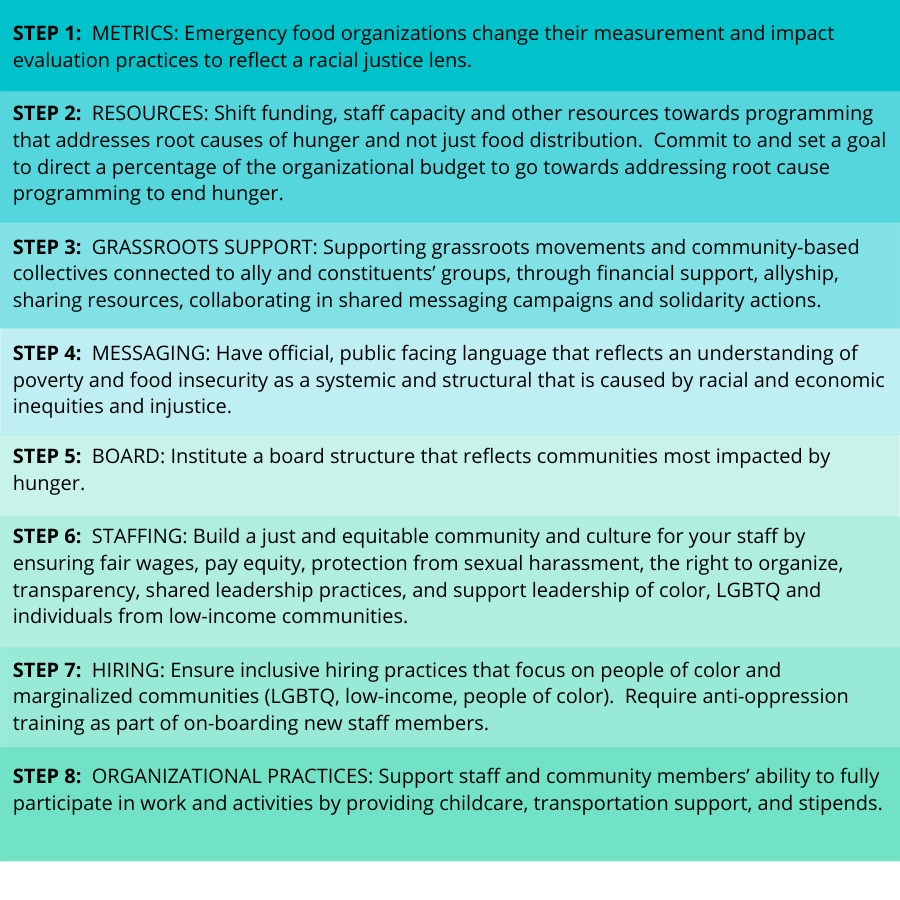

SUZANNE BABB: Closing the Hunger Gap is a network of emergency food and food access and anti-hunger organizations that have realized that charity is not the answer to hunger and that organizations really need to shift their work from one based in charity to one based in justice. That food distribution alone is not solving the problem.

And so our major goal is really to be a support system for organizations to make that shift, to provide a collective voice that speaks out about the root causes and challenges the dominate narrative. because often times organizations feel like they can't do it on their own, whether it's because whose funding, or maybe their food bank controls them in terms of what they can for advocate for. But this is a collective voice that can speak out against that.

And then also how do we use whatever power and resources that we have to support the grassroots frontline organizations that are doing this work? Because that's where we really will lead resources need to be funneled. Not to emergency food providers to further institutionalize us, but supporting the work that grassroots organizations are doing.

So we do that in several ways, we've had a conference every two years. We have a leadership team that helps to coordinate the activities. Since the pandemic hit we started to have biweekly member meetings where people could just talk about what's been going on in their community, what's been challenging, and what people have been able to do to kind of see their way through those challenges. And there's talk about like what is this highlighting, these kind of things that we've been talking about with kind of root cause issues.

And also been doing some regional work. Recognizing that people really want to know what's going on in their region. And each region is dealing with different issues. And so thinking collectively about what they can learn from each other and what's kind of the work they can take on together.

And then we have a community of practice around racial equity which is just an informal space for folks who really wanna dig in and deepen their learning around that.

And we also have a working group around narrative change that's really looking at what is the dominate narrative, how do we challenge that narrative, what is the new and the true challenge that we wanna see knowing that narrative, the narrative that we use is tied into the solution. So we envision doing a lot of work around that and what we're trying to do now is beginning to create a national narrative campaign.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Closing the Hunger Gap is also documenting stories of organizations who have done this transformational work as a resource for those who don't quite know where to start.

SUZANNE BABB: I think that it is important for people to have that resource, and I really think it's important for people to do their own work. If you're a white person you really need to read about whiteness and white supremacy and how you embody that, how your organization embodies that. If you think about if you're mostly in a white line nonprofit that is working with communities of color, if none of you have examined the way in which whiteness plays a role personally and the way you're doing organizational work, that is gonna impact the way you do work with communities of color.

And that is the way a lot of it this work operates, especially around food access. Right? You know people come in with the solution and they just roll out these programs for these communities without a consultation. That is grounded in white supremacy and this idea that... your ideas and because you have the resources that you're superior and you know better than the communities. The communities are living it! They know what's wrong, they know what needs to change. The often times just don't have the resources to do that.

And so instead of coming in thinking that you know what people need to do, come in and ask. It's like you can't do anything about being white but you can recognize the power and privilege that you have, how that plays out and then ask yourself how do you use that power? And then for people's color we need to investigate the way that we internalize the oppressions that we hear, and we need to do the healing work for that. Think about how we then use that healing to do the work to help support our communities.

So we've all got work to do. A lot of white people get caught in guilt and shame and defensiveness, and we're all impacted by it and we can't think that we're not. So recognize how you're impacted by it, and then how do you use that to for us to achieve racial equity.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: For all of us to achieve racial equity, that's the goal isn't it? That was Suzanne Babb of Why Hunger, La Finca del Sur and Black Urban Growers. Check out our website for information on closing the hunger gap and other resources Suzanne mentioned in our conversation. Find us at EarthEats.org.

(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

That's all we have time for today, thanks for joining us. Stay nourished, stay safe.

RENEE REED: The Earth Eats team includes Eobon Binder, Chad Bouchard, Mark Chilla, Abraham Hill, Taylor Killough, Josephine McRobbie, the IU Food Institute, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed. Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey. KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week to Suzanne Babb.

Production support comes from:

Insurance agent Dan Williamson of Bill Resch Insurance. Offering comprehensive home, auto, business and life coverage, in affiliation with Pekin Insurance. Beyond the expected. More at 812-336-6838.

Bloomingfoods Coop Market, providing local residents with locally sourced food since 1976. Owned by over 12,000 residents in Monroe County and beyond. More at Bloomingfoods.Coop.

And Elizabeth Ruh, Enrolled Agent, providing customized financial services for individuals, businesses and disabled adults including tax planning, bill paying, and estate services. More at PersonalFinancialServices.net.