(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington Indiana, I'm Kayte Young and this is Earth Eats.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: Winter-kill cover crop is like the most beautiful thing because it's gonna do all of the work for you, basically, and get you to where you need to.

KAYTE YOUNG: This week on our show we speak with IU campus farm manager Erin Carmen-Sweeney about regenerative agriculture practices and how they can come in handy when you start a farm on land without any topsoil. Harvest Public Media has a story about President Elect Joe Biden's choice for Secretary of Agriculture and we have some recipes suitable for the holiday season. Stay with us.

(Music)

Earth Eats is produced from the campus of Indiana University in Bloomington Indiana. We wish to acknowledge and honor the indigenous communities native to this region and recognize that Indiana University is built on indigenous homelands and resources. We recognize the Miami, Delaware, Potawatomi, and Shawnee people as past, present, and future caretakers of this land.

Let's start with Earth Eats news with Renee Reed. Hello Renee.

RENEE REED: Hello Kayte. As farmers close out the year many will be turning some attention to signing up for safety net programs. Harvest Public Media's Amy Mayer reports on the changing role of federal payments.

AMY MAYER: In the 2014 Farm Bill congress created the agricultural risk coverage and price lost coverage programs to replace a safety net system that simply cut farmers a check each year. Iowa State Extension farm management specialist Steve Johnson says there was little expectation in 2014 that farmers would see large payments from ad hoc programs. But this year the combination of trade bailout money and coronavirus relief has pushed farm income higher than it's been since 2013.

STEVE JOHNSON: That is the biggest surprise. I think that congress intended to sunset the direct payments ARC creating PLC and then here comes the ad hoc payments and now ARC/PLC still exists, and it'll exist for three more years.

AMY MAYER: Farmers can sign up for ARC or PLC through March, but Johnson advises them to use crop insurance as their main risk management tool. Amy Mayer, Harvest Public Media

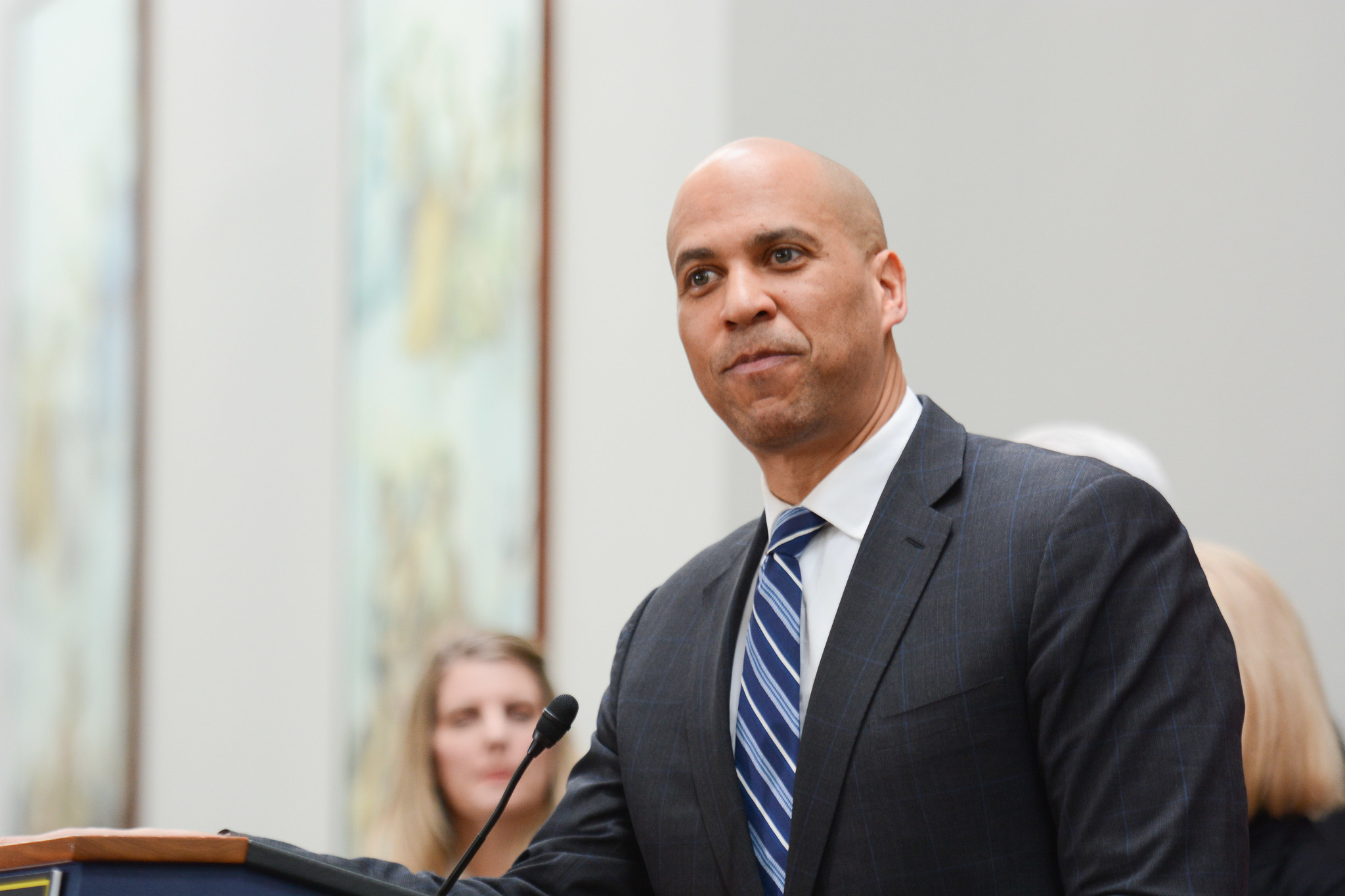

RENEE REED: A new bill called The Justice for Black Farmers Act aims to reverse decades of discriminatory practices by the USDA. The bill was brought forward by senators Cory Brooker, Kirsten Gillibrand and Elizabeth Warren.

In the last 100 years the number of black farmers in America has decreased from 17% of all producers to less than 2%. For decades black farmers have reported being denied access to loans from the USDA or facing a much longer approval process than their white counterparts. The act aims to restore land lost by black farmers by providing land grants of up to 160 acres to existing and aspiring black farmers. It would also create farming and ranching education programs for young adults from socially disadvantaged communities.

Kamal Bell CEO of Sankofa Farms, a family farm and agricultural academy in North Carolina told ABC news that he sees the bill as a step in the right direction. However he says the education aspect of the bill should focus on more modern business and farming practices. The act does have the support of the National Black Farmers Association, the USDA Coalition of Minority Employees, the National Farmers Union and over 100 other organizations. While moving the bill through congress will be an uphill task, senator Brooker told Mother Jones he thinks there is growing momentum for addressing the legacy of discrimination in the U.S.

Thanks to Toby Foster and Harvest Public Media's Amy Mayer for those reports. For Earth Eats News I'm Renee Reed.

(Earth Eats News Theme)

(Music)

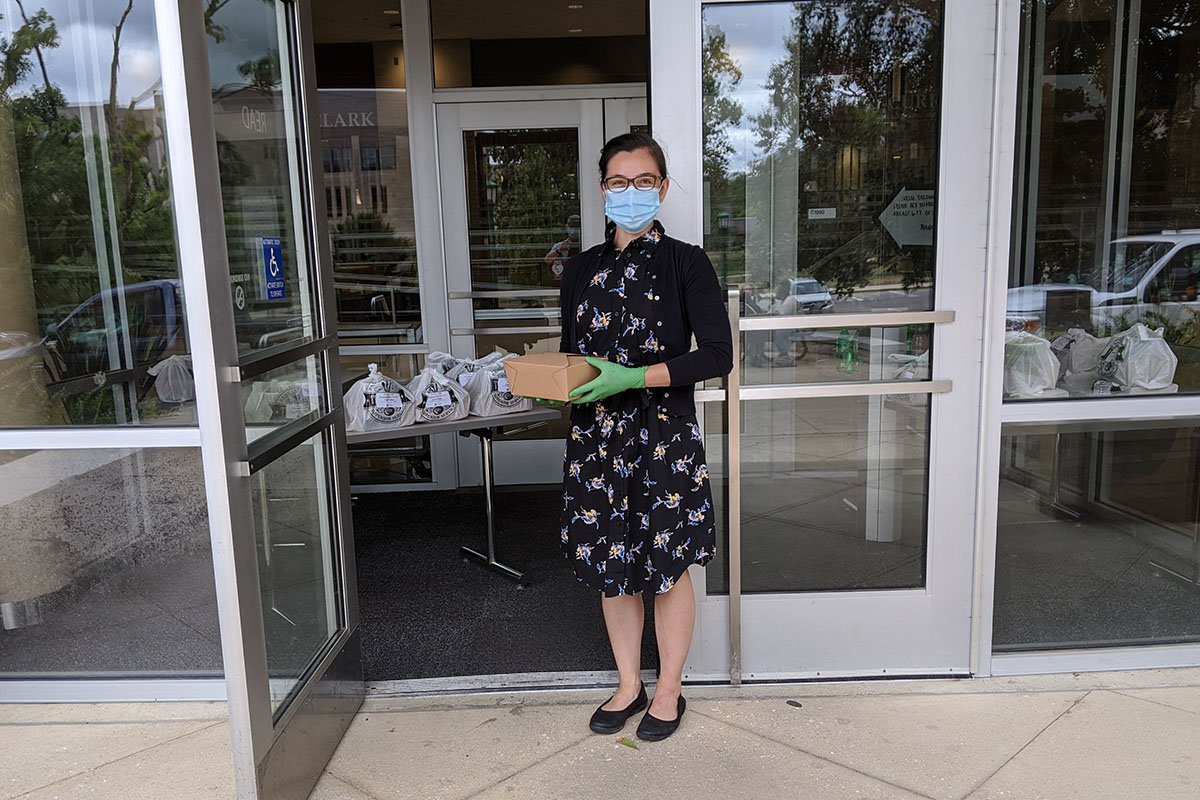

KAYTE YOUNG: When schools closed, and businesses began to shut down due to COVID-19, organizations and individuals stepped up to help people who may have suddenly lost income or otherwise needed assistance. On the campus of Indiana University, the IU food institute suspected that there were people in the IU community who might need help with meals.

CARL IPSEN: We were thinking about students who had supported themselves with jobs maybe in the service industry, and everything was closed. All the restaurants were closed. And you know what kind of situation were they facing.

KAYTE YOUNG: The director of the IU Food Institute saw an opportunity to help.

CARL IPSEN: Carl Ipsen, I'm a professor of history at IU Bloomington and the director of the IU Food Institute.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, he started a conversation with the Executive Director of IU Dining.

RAHUL SHRIVASTAV: My name is Raul Shrivastav.

CARL IPSEN: In the conversation it emerged, the IU dining staff was still employed but obviously feeding many fewer people because the dining halls were for the most part closed. Well we have the cooks, but we don't have the ingredients - we don't have the foods for them to cook, so we need to find a way to get that.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, Carl appealed to a list of people associated with the IU Food Institute and sent out a call for donations.

CARL IPSEN: Using the Food Institute and the context we have there, and sort of with the foundation, doing some fundraising among alumni, and...

KAYTE YOUNG: They quickly raised the funding they needed to get started and spread the word about the emergency meal project.

RAHUL SHRIVASTAV: I think it was four days that we pulled this off. We talked about it on Thursday, by Monday morning we were serving our first meals. David and Ashley were key in this area, they started developing menus based off locally provided foods from the IU farm and local ingredient providers that we have.

Along with the chefs led by Ashley Massie and David Talent we had a good systems team that took this all on, prepared a form that students could order these meals from, put in their preferences and allergies. Ashley Massie, she had the whole form laid out, how it transfers to a spreadsheet, whose on the delivery piece of it, who's coming and picking it up - as you saw a couple of cars just drove by here picking it up. She had all that organized.

KAYTE YOUNG: They set up a system. An online ordering process, a time and a place for meal pickups, and a delivery process for those who can't make it to the pickup spot.

RAHUL SHRIVASTAV: And through the Food Institute intern and the campus kitchen intern, we have been able to deliver meals to people who are for whatever reason, whether they were quarantined, or didn't have transportation, or maybe even were sick, couldn't make here. So, we've been doing deliveries everyday as well.

KAYTE YOUNG: And it worked out. By the 12th week in early July they had provided more than 3,5000 meals and they had their biggest day that week, 101 meals in one day. Of course, I wanted to know about the meals themselves. What kind of food were they serving?

RAHUL SHRIVASTAV: Today there was a vegan pasta with a great vegetable sauce and sautéed snap peas which are in season right now. There is a full meal, it's highly nutritious. There's salad, there's an entree, and very well portioned. It can be stretched out of lunch to a snack or even dinner at times. The food's been amazing actually and yesterday, just yesterday there was stir fried rice. I'm vegan so I'm gonna give you the vegan descriptions so... it was stir fried rice with a lot of vegetables in it, and it was absolutely delicious. And I know the non-vegans got pot stickers, which was made from scratch over here so... the chefs are getting... it's also very good for our staff, you know? They're getting... you know during this break, when you're cooking you need some momentum, okay, you know, you keep going with it. And right now, they're cooking and innovating more and more and so it has been a lot of... it has been a lot of fun with them, with the meals.

KAYTE YOUNG: Carl and Rahul are brainstorming and working with the administration on more stable and sustainable ways to address food insecurity on campus. We first shared this story in the late summer, the program was suspended during the fall academic semester since regular meal programs were in place. The campus emergency meal program is back for the long winter break. Find more information at Earth Eats dot org.

(Music)

(Music)

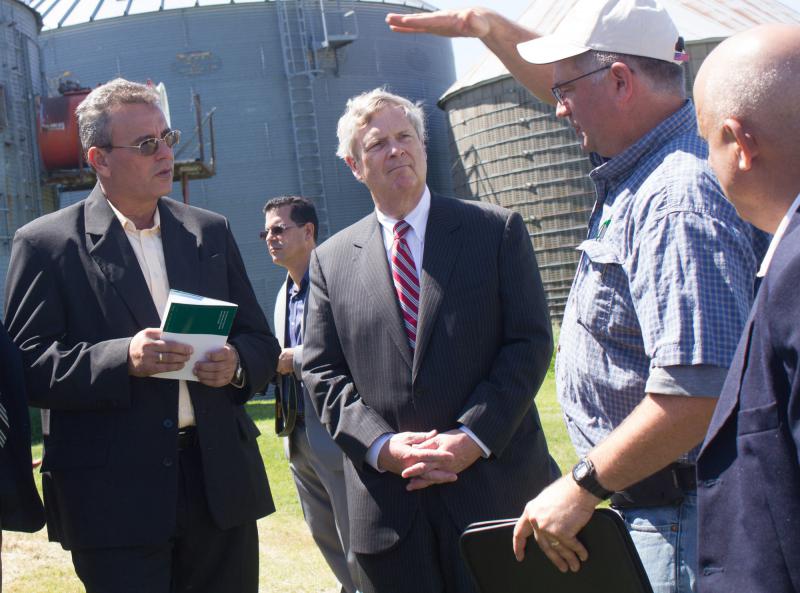

Tom Vilsack served as the Secretary of Agriculture during all eight years of the Obama administration. President Elect Joe Biden is looking to tap into that experience by picking him to return to the job. But as Harvest Public Media's Jonathan Ahl reports Midwest farmers and advocates from both sides of the political spectrum, have some major concerns.

JONATHON AHL: Tom Vilsack isn't a farmer, he's a lawyer who grew up in Pennsylvania and moved to his wife's hometown in Iowa in the 1970's. He rose through the political ranks to become governor of the state and then went on to serve as secretary of Agriculture. Keith Bockelman is a political science professor at Western Illinois University. He says Vilsack is a moderate and a safe choice.

KEITH BOCKELMAN: It looks like it's kind of somebody that Biden was comfortable with clearly and so in some ways I think that this is kind of a compromise choice.

JONATHON AHL: A compromise that longtime republican senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa is supporting. In August of 2019 Vilsack joined Grassley at an Iowa dairy to promote the new north American trade deal. Grassley said Vilsack is someone he can work with.

SENATOR CHUCK GRASSLEY: When everybody thinks everything in Washington is partisan and there's opportunities to stretch bipartisanship, and with somebody of Governor Vilsack's background particularly Secretary of Agriculture for eight years, it brings credibility to the chance that this is something that we can get done.

JONATHON AHL: But rank and file farmers of differing political persuasions don't see Vilsack that way. Larry Sailer is a semi-retired farmer who grows corn and soybeans on 200 acres in northern Iowa. Sailor voted for Trump and says he doesn't trust Vilsack because of his history of increasing government regulation on farmers. He says an example is Vilsack's support of more stringent rules to enforce the clean water act.

LARRY SAILER: Those types of regulations don't really do anything to improve the conservation, the quality of water, anything. So to me it's just a regulations are a drag on the economy on farmers, basically on anything.

JONATHON AHL: Even farmers that voted for Biden aren't thrilled with the choice. Darvin Brantledge has a hundred head of cattle and cornfields on his 1,200-acre farm in western Missouri. He says he expected more from Biden and that Vilsack is too cozy with corporate agriculture and a lot more consolidation of crop and livestock production shutting out small farmers.

DARVIN BRANTLEDGE: He had listening sessions where he wanted to listen to farmers, but they more or less turned into his promotion towards more corporate control.

JONATHON AHL: Adding fuel to that criticism is Vilsack taking a job leading the U.S. Dairy Export Council after leaving Obama's cabinet. That trade group was seen as an ally to large producers. Another criticism of Vilsack is his lack of action to help black farmers. Jeanette Mott Oxford is the director of policy at Empower Missouri, a food shelter and justice advocacy group. She says helping minority farmers is an issue that has gone unaddressed for too long.

JEANETTE MOTT OXFORD: There wasn't much improvement on that front under Vilsack and we would help that the Biden administration would commit to finally making things right for black farmers.

JONATHON AHL: Mott Oxford says Vilsack was strong on the nutrition and food aid side of the USDA's mission with increases to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP, especially during times of recession. But more left leaning groups wanted someone even more dedicated to that cause and less focused on the business of farming. But political scientist Keith Boeckleman says agriculture is an area where the Biden administration may need to seek middle ground and compromise more than pushing an ideological agenda. He says Vilsack as a compromise candidate can forge bipartisan agreements.

KEITH BOECKLEMAN: It also becomes a matter of how effectively he can lobby congress. When he was appointed the first time under President Obama he was unanimously supported and accepted. So I think he had some political capital in congress.

JONATHAN AHL: But first Vilsack will have to be approved by a very divided and very partisan senate. Jonathan Ahl, Harvest Public Media.

(Music)

KAYTE YOUNG: Find more from this reporting collective at Harvest Public Media dot org. After a short break we'll visit a farm on the campus of Indiana University. Stay with us.

(Swanky Music)

I'm Kayte Young, and this is Earth Eats. One of the sources for food for the campus emergency meal program over the summer and for IU dining in general is the IU campus farm. Early in the fall I visited the farm and spoke with the farm manager Erin Carmen-Sweeny.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: We are walking around the IU campus farm which is at the Hinkle Garden Farmstead.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: The farm is located on 10th st, west of the bypass in Bloomington. They focus on fruit and vegetable production and distribute the harvest to students through IU dining services, to the general public through farm stands, and to those in need of food assistance through donations to Mother Hubbard's Cupboard. Erin Carmen-Sweeney grew up on an organic farm, but truly discovered his passion for sustainable food systems after he left home.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: I went off to college and the summer reading that they made my entire freshman class do was Omnivore's Dilemma and it was like wow, you know the world is trying to teach me that the way I've been raised and grown up is a good an important way to be producing our food in the way we should be producing our food.

(I) got more interested in it from a different perspective, it was never like an academic thing for me growing up. It was just like this is what we do, and then I started to study and realize all of the problems with the larger industrial food system.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Erin has a degree in geography and environmental resources and loads of experience in growing food and sharing farming skills with others. He's been running the farm from the beginning and it's a good fit. With about five acres for crop production, the farm hosts four high tunnels and several large open airfields for growing specialty crops. Erin gave me a tour of the farm at peak growing season starting with the first area they planted.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: This is our main growing area for 2018-2019 and this year because this is the only part of the property where the soil wasn't stripped, all the topsoil wasn't stripped away.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: The farm faced a huge challenge when they first broke ground in 2017 due to the condition of the land itself. At some point one of the heirs of the garden estate was looking at developing the site for condos or apartments and sold off the topsoil.

[TO ERIC] I didn't even know that was a thing that you can sell topsoil.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: Oh yeah, people buy topsoil. You can go to Speedway and buy topsoil and it's just you know soil that they stripped off the land somewhere because they wanted to flatten it. Anytime, if you're anywhere near a building the topsoil that you're dealing with is very likely not the native topsoil.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Okay, good to know. Earlier I said the farm is dedicated to growing specialty crops. What that basically means is fruits and vegetables as opposed to corn and soybeans which are the typical Indiana crops.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: Beans there's some kombucha squash, butternut squash, more beans for the fall. This is our zucchini that we're just starting to pick so it's kind of... the timing has worked out to where like that stuff is fading and this stuff is just coming on. We've got a big row of a couple different colors of pink and yellow tomatoes, more beans, some peppers, there goes a rabbit! And some cherry tomatoes, and then this is our first year growing sweet potatoes.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: In spite of the land being stripped down to hard pan clay, they've managed to build up the soil through an approach called regenerative agriculture. This includes methods such as winter-kill cover cropping.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: Cover crops are great for a lot of reasons, which most people look into, but basically just having living roots in the soil. And then what I like to do is have a nice mixture of different plants and not just a single thing. Because the diversity basically when it dies, it can compost in place and provide those nutrients. And for a couple reasons, that's a lot cheaper than buying compost.

And you know people say well "Why don't you just make your own compost?" well at the scale that I'm at, I would need like industrial quantities of compost, and huge equipment to turn. So a cover crop can kind of create that biomass, that organic matter in plates. And then the nice thing about a winter killed one, is that terminating it is not a problem, it's gonna die. So it's you know a warm season crop, like a buckwheat, this'll probably be like sorghum Sudan grass, sun hemp and buckwheat, which are all gonna die at the very first frost.

And then they'll just be able to break down and be a mulch all winter, so they'll protect the soil and then by the time the spring comes around, almost all that material has fully like broken down into the soil. You might rake aside a little bit, but you can just get right into the soil and it's ready to go, and it's added some nutrients, and if you have a legume in there like in our case the sun hemp, it's gonna have some nitrogen for you.

So that's kind of our main fertility program because compost is just expensive and not always attainable, and obviously we're using organic methods so we're not bringing in like ammonium nitrate or anything like that.

Because we use cover crops and the way we approach farming, we call it regenerative agriculture. Trying to build life in the soil with all these different roots in the soil that attract different various microbes and fungi relationships. Like a winter-killed cover crop is the most beautiful thing because it's gonna do all the work for you basically and get you where you need to.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Some areas of the campus farms are used for research and experimentation, a sort of living laboratory for classes at IU. Textile artist and IU professor Rowland Rickles is growing indigo on the campus farm for projects in natural dying. Professor James Farmer who oversees the campus farm brings his students out for hands on learning in sustainable agriculture, and biology professor Heather Reynolds is conducting a trial on the use of living mulch.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: So this like the living mulch of the clover is here, and she has a map of it so she can tell me better, and I think this one is like a...

KAYTE YOUNG [TO ERIC]: Vegetables or something

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: Vegs and rye that got mowed down. Then there's the straw one, and this one is a leaf mulch, stripped mulch. So there's these different mulching approaches, they're all no till, seeing which is most effective. And she did this trial, a larger scale trial, it took up this like whole plot last year, and she did on two other farms. And universally it seemed, I think, to find that the straw mulch was the most effective and that was pretty much the farmer control of what would you normally do? And so the living mulch is all the kind of more experimental stuff was found to be less effective. But there might be reasons to tweak it and try something else, try something slightly different.

KAYTE YOUNG [TO ERIC]: And maybe if it works but isn't the most effective, but it still works then maybe it's still worth trying out.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: Yeah, totally.

KAYTE YOUNG: So this part over here looks more traditional with the straw.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: Right, right. Effective but...

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: One of the agricultural experiments on the farm is managed by Erin and the other employees of the farm.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: Basically we're comparing the open field to the movable high tunnel to the permanent high tunnel and seeing just how they perform. We're growing the same crops; we've got tomatoes and peppers in each of these spots for the summer anyway. A lot of people want to grow tomatoes in their tunnels because it's just a highly profitable crop and it's a good space to grow that. So they'll build the tunnel, and then they'll want to do that year after year. And it's like well, okay that's not great for the soil.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: With organic growing methods it's not great for the soil to plant the same crop in the same place year after year because you can end up harboring pests and diseases in the soil that affect that particular crop. Ideally you rotate your crops so that one piece of land would have say tomatoes one year, then green beans the next year, then carrots the following year, and then you could return to tomatoes. Different types of crops deplete the soil of or supply the soil with particular nutrients as well.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: But by having a movable tunnel I can move my tunnel and be growing tomatoes in it again next year on a new patch of ground that didn't have tomatoes in it last year.

KAYTE YOUNG [TO ERIN]: And grow something else where the high tunnel was.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: Yeah exactly, and it encourages you, again those cover crops a lot of people don't ever plant cover crops in their tunnels because you want to do... you know your tomatoes in the summer and then you do your leafy greens in the fall and winter and you’re kind of always have it in some kind of cash crop. It's too valuable space to not do something like that. But with being able to move the tunnel then you have outdoor space where you can you know throw in the cover crop and kind of get a chance to revitalize that soil.

KAYTE YOUNG [TO ERIN]: Okay so you're calling these moveable tunnels but to me they look huge and really hard to move so what...?

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: This is all, there's a rail here, and this is a track. There's wheel on the rail, and then everything is just anchored in. So these cables connect it to the rail and then there's earth anchors there, but all that stuff comes right off. And then the walls flip right up, and then we've moved this with as few as four people. Just push it down the track. You get a little grease on the ball bearings on the wheels and yeah it runs right along.

(Sound of track moving)

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: So yeah, these building size structures, the size of say a double wide trailer. They're basically an arched metal frame covered with translucent plastic sheeting. They're on tracks. You move them by rolling them on the tracks.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: And we planted lettuces and greens and once that stuff was established and looking good, we moved it along so that we could go ahead and get our tomatoes planted and stuff for the summer.

KAYTE YOUNG [TO ERIN]: And you've got carrots galore right now it looks like.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: Yeah replace that with carrots, yup. And then all of the first plot where it was, that's where it was over the winter, that's now all in a cover crop.

KAYTE YOUNG: Oh so there's like three sections total?

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: There's three sections, yup, yes.

KAYTE YOUNG: That's so great, I love it.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: Yeah it's fun.

(Swanky music)

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: I really couldn't get over the brilliance of the system. It allows the grower to continuously use the covered structure season after season while rotating the crops for optimum soil health. This kind of research on the campus farm involves a lot of record keeping and documentation.

ERIN CARMEN-SWEENY: Just the recording of the data from the different tomato plots is about 25% of the labor of harvesting the tomatoes. Right? So there will be like three people harvesting tomatoes and then one person like weighing them and being like, "Okay this is from that plot, this is from that plot" and put it into a spreadsheet.

Record keeping it's a big part of it, and that's an aspect of research, an aspect of food safety, and just like good farm management, and knowing what amendments went down where, and what was planted where and keeping track of everything.

KAYTE YOUNG: That was Erin Carmen-Sweeny of the IU campus farm, you can find more about the farm on our website EarthEats.org.

(Music)

At our house we have an eclectic collection of mugs. And lately I've noticed that my relationship with them is rather involved. We have ones that were handcrafted by my friend Libby. One from the dentist office in Terra Haute where my son had dental work done at age 1.5. There's the kitten mug with a picture on the front and a small circle of the kitten image on the inside so you never lose sight of the kitten even when taking a drink. There's the mug from Wanza construction from way back in the days when I worked in the building trades - that's the one I pick up when I've got a serious workday ahead and I need to buckle down and power through.

The kitten one is for days when I need to be nice to myself. The one from a local law office has a nice weight to it, it feels good in my hand and it's a great choice for day-to-day getting stuff done. The handcrafted ones are luxurious and comforting at once. My partner often uses the dentist one since we don't care if it gets tea stains. There's one with an elegant Sohio logo on it. It's a narrow mug that fits perfectly in the car cupholder. But I hesitate to take it out of the house for fear of breaking it. It is a favorite. The plain dark blue one can travel, it's replaceable. Same with the one from the Hub, I have a second one stashed away.

But the best mug in the world is one that my former coworkers had custom made for me that says, "I have lots of ideas". It makes me feel seen and known and loved. I miss that one. It's been hanging out at the office without me for nine months. Maybe I should go by and pick it up.

Anyway, the point is mugs can be special. We can get attached to ordinary objects. If you're looking for a new mug to enter your life, maybe you could request one from WFIU as a thank you gift when you make your donation. Public radio always has good mugs. Your WFIU mugs could be the one you use when you're feeling generous, community minded, proud of yourself, or well-informed. There's still time to make a gift before the end of the year to take advantage of the CARES act tax benefits. You can pledge your support now by going to WFIU dot org slash donate. And thank you.

(Music)

Holiday baking is a tradition in my family. My mom always baked several kinds of cookies and prepared a batch of peanut brittle before Christmas. Then we'd arrange them on gift plates for neighbors and friends. I carried on the tradition, adding savory roasted nuts and granola to the list of sweets. Since I'm making many different goodies in a short time span, I appreciate a recipe that comes together quickly. This chocolate truffle recipe fits the bill, and comes from another family member, my brother in law - Eric Pearson.

Eric lives in Paint Lick Kentucky, near Berea. He teaches philosophy at Berea College. Eric is a great cook; he's always exploring new recipes and cookbooks. He's known for hosting elaborate dinner parties, and he's dabbled in molecular gastronomy with his son Clem. But today he's sharing something decidedly uncomplicated. The recipe is called Daily Dose - Extra Strength Truffles. Here's Eric.

ERIC PEARSON: I've got a couple tablespoons of cold butter here that I want to chop up into little pieces. You need eight ounces of chocolate, and typically I get it in... this is dark chocolate. I usually get it in bars and chop it up, but today I have it in handy dark chocolate chunks, 72% already chopped up. Now you can use any chocolate you want, any dark chocolate you want, and the only other thing we're gonna use is cream, and then at the end we're gonna dust it with cocoa powder.

So, the first the thing I'm gonna do is put 10 ounces of my chocolate chunks into a bowl. And then add the butter. And now we take a cup of cream out of the refrigerator... here it is. And we're gonna put that on a small pot, on the stove, over low heat. You're gonna heat it up but of course you don't want it to boil, just to where it gets steam coming off it. If anybody's warmed cream the range top, you know that you probably want to stir it pretty much constantly. If you don't do that a film forms on the top of the cream, which doesn't help anything. And this will take a few minutes.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, where does this recipe come from?

ERIC PEARSON: I found this recipe just in the food section of a local newspaper in the Lexington Kentucky Herald-Leader. And I don't think that the author of that credited to anywhere else. The author said that this was the best thing for the hassled mother of two.

KAYTE YOUNG: Uh-huh.

ERIC PEARSON: So, recommended them as a medical intervention in the middle of the day.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, the cream is just heating until we see the steam coming off of it?

ERIC PEARSON: Exactly right. And that's just hot enough to melt the chocolate and the butter. And there's the steam, so... turn off the burner, and pour the cream over the chocolate and butter.

Take a whisk, and just whisk until all of that is melted into one mass.

I've whisked that until it is smooth, and that’s all. And now I'm gonna pour it into a prepared loaf pan. I like a loaf pan with as straight as sides as you can get, and then you want a piece of plastic wrap large enough so there's enough to go over the tops.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICE OVER]: Eric lines the loaf pan with the plastic wrap.

ERIC PEARSON: And now I am pouring the melted chocolate mixture into the prepared loaf pan. If you can't get it all out, there's enough for the kids to lick the bowl. Now fold over the excess plastic wrap, and we will refrigerate until set, several hours.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Before you take the set chocolate mixture out of the fridge, dust a cutting board with a generous amount of cocoa powder.

ERIC PEARSON: So, the truffles have been in the refrigerator for about eight hours. So, take them out with the plastic in one big piece, unwrap the plastic...

KAYTE YOUNG: And place your slab of chocolatey goodness onto the layer of cocoa powder on your cutting board.

ERIC PEARSON: Now we're gonna cut these into 32 pieces, but first we wanna top it with the cocoa powder, and smooth it out all over it. And when we cut it up, we're gonna have cocoa powder on... we wanna powder all six sides of each cube.

KAYTE YOUNG: I recommend making one cut down the center and then dividing each half into four equal pieces, so you end up with 32 more-or-less evenly sized cubes. These are pretty big truffles so you could cut them smaller if you like.

ERIC PEARSON: And now what you do, you pick each one up, and you dust it in the remaining cocoa powder, and then you put them back in the loaf pan in layers. I use wax paper between the layers.

KAYTE YOUNG: You'll wanna keep these in the fridge until you're ready to serve them. They'll get too soft at room temperature.

I can't get over how simple these are to make, and how elegant they end up looking with that matte dusting of cocoa powder. And these truffles are delicious with a deep flavor and a creamy texture, and definitely not too sweet. They're perfect.

Well thank you very much, Eric.

ERIC PEARSON: You are welcome.

KAYTE YOUNG: Of course, you'll find this recipe and many others on our website, Earth Eats dot org.

(Music)

RENEE REED: Make sure you never miss an episode. Subscribe to our podcast. It's the same great stories in your podcast feed. Just search for Earth Eats wherever you listen to podcasts. While you're there, please leave us a review. We'd love to hear from you and it helps other people find us.

(Music)

KAYTE YOUNG: So much of my holiday baking traditions involve sweets - cookies and candy mostly. But for years I’ve also included a granola recipe, and it's always a bit hit. This is a very simple granola recipe; you can customize it to your taste. It makes a great gift around the holidays. Start by preheating your oven to 250 while you mix up your ingredients.

The first ingredient is oats... rolled oats, and you definitely want the old fashion; you do not want to get the quick oats. You can also make this a gluten-free granola by making sure that the oats you purchase are 100% gluten free, some oats are not. So, you want eight cups of rolled oats.

Next ingredient is chopped nuts. You're gonna want a cup of chopped nuts and it can be whatever nuts you prefer. Today I'm making it with pecan, but I often do it with almonds. This is a rough chop. I really like to have nice big pieces of nuts in my granola. You're gonna want one cup of chopped nuts, and then you just wanna mix those nuts in with the rolled oats. Now I mix up my oats and my nuts in one big baking sheet, sort of a roasting pan kind of thing. It's just a big metal pan. I mix it all up in there so that I don't even have to dirty a bowl.

And then we're gonna mix up the oil and the maple syrup. So, it's one-half cup of maple syrup, and one-half cup of oil. I'm using a sunflower oil. I mix this all up in one two-cup measuring cup, and then two or three generous squirts of honey. And then one-half teaspoon of salt, this is also the time where you can add other seasonings if you prefer. Some people really like cinnamon, or nutmeg, or cloves, or allspice, or any kind of spices that you think would be interesting or desirable in your granola.

You're gonna mix up that oil and serve together and the honey and get it really thoroughly mixed. And then you're gonna pour that directly over the oats and the nuts. You want the syrup and the oil mixture to fully coat all of the oats and the nuts.

Once the oats and the nuts are fully coated in the syrup and oil mixture, then it's ready to go into the oven. You're gonna wanna kind of shake it down to an even layer, and then put it in the oven. And once you get your pan in the oven set your timer for 15 minutes.

And once your 15 minutes are up, you're gonna take it out and stir it, put it back in the oven for another 15 minutes; do that until it’s a nice golden brown. And once your granola turns a deep golden brown, should be done in about hour... hour and 15 minutes. And before it cools you wanna add your dried fruit if you're gonna be adding any. So that would be your raisins, or your currants, or you can use dried cranberries, you could use chopped apricots, figs... whatever you prefer. I'll be using dried cranberries, and I think even the cranberries are a little bit too big; so, I usually chop them up a little bit before I add them. Just mix the dried fruit into the hot granola, and you're done, just let it cool, and you can store it in jars, or airtight containers.

Fill up a pint jar, put a ribbon on it, and it's a great holiday gift. Hopefully there's enough left for you. I enjoy this granola for breakfast with a dollop of plain yogurt and fresh berries, or homemade jam. The recipe is on our website, Earth Eats dot org.

And if you are a visual learner you can watch a video of me making this recipe in my home kitchen. It's on the Earth Eats YouTube channel. Find us by searching for Earth Eats on YouTube. You'll find at least one cookie recipe there as well and while you're there you might as well subscribe.

In this next story we'll get a taste of the Oregon coast courtesy of producer Josephine McRobbie and public folklorist Joe O'Connell. It features the voices of commercial fishes and seafood entrepreneurs. It was recorded in August 2019. O'Connell conducted the original research for the Oregon Folklife Network with support for the National Endowment for the Arts. J

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Hoppy micro-brews, Tillamook Cheddar, Pinot Noir, these are a few of Oregon’s favorite flavors. But there’s also something in the water.

(suspenseful music)

LAURA ANDERSON: What we have out here in our ocean is very special. We have these cold-water fish.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Salmon, tuna, halibut.

LAURA ANDERSON: They have high oil content, they’re good fish, they’re fatty and they just taste awesome compared to skinny little tropical fish (laughs), in my opinion, and in many people’s opinions.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: It takes hard work to bring fish and seafood to the plate. Laura Anderson, Amber Novelli, and Terry Hartill are all small-scale seafood entrepreneurs. Laura owns Local Ocean, an upscale restaurant and market on Yaquina Bay in Newport. Just across the street, fishing boats dock at Pier 5. Some of these boats are her direct suppliers.

LAURA ANDERSON: We have relationships with over 50 different fishermen to get the catch required to feed on a day like today, in the summer, in August, we might feed 900 meals today.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Amber and her husband fish from two boats, the Midnight and the Aquarius. They bring their catch directly to customers at their small floating seafood market in Florence.

AMBER NOVELLI: And that’s one of the biggest things--when people come to the coast, they're looking for fresh fish. They're not looking for something that is frozen, that could be farmed, that could be anything. You want what is caught here.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: In the town of Seaside, there's a giant, glowing, neon crab. That sign marks Bell Buoy of Seaside, where Terry oversees one of the coast’s few remaining seafood canneries.

TERRY HARTILL: There were all kinds of canneries back in the 1800s. There were 20 canneries along the river. Now if you don't home-can yourself, in your own kitchen, your own product, where else do you get it? You have to come to people like us.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Fishing, canning, running a restaurant -- these are all pretty distinct business ventures. But these three entrepreneurs all have roots in seafood.

TERRY HARTILL: Yes I was born and raised in this area. I've been in the seafood business since 1966, in some capacity.

AMBER NOVELLI: My husband and I are both from from Monterey, California, they have a huge squid population down there. The Italians have huge industries down there, a lot of old school families.

LAURA ANDERSON: I grew up in Westport, Washington, it’s a very small fishing community, probably had a population of less than 1500 people. Most of them were fisherman or fishing families and my dad was a commercial fisherman.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Keeping these family and community legacies going involves careful thought and planning. To bring fish to market, local producers navigate a dynamic set of state and federal rules.

AMBER NOVELLI: I can imagine if we were all just out there catching with absolutely no regulations, no size limits, no amounts of what we could catch, then we would be destroying the ocean. But we all have our part in what we do to keep everything sustainable.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Take for instance one local delicacy, sweet flavorful razor clams. To sell them, Bell Buoy needs the correct license.

TERRY HARTILL: Razor clams, We’re the only ones in the state of Oregon that can process razor clams.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: The diggers Terry buys from need the correct licenses

TERRY HARTILL: You have to have a human consumption license. If can’t have a sport license, you’ve gotta have all the proper paperwork.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: And the digging has to take place on the clams’ calendar.

TERRY HARTILL: We have about a dozen commercial diggers that dig for us when the season’s open. Currently, it’s closed because of the spawning of the clams October first then it’ll re-open all the way to July 14th again.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Species-specific measures like these are standard. They foster a balance between food harvesting and ocean health. Amber wonders if outsiders to the industry understand the extent, and the rigor, of environmental regulations.

AMBER NOVELLI: I don't know who they think writes these rules, it isn't just some redneck sitting in a hut. It's biologists, it's scientists. It's people that know this stuff that set us up with it and tell how you can keep a species in check.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Like Amber, Laura is protective of commercial fishing. She’s not only a restaurant owner, she’s also studied ocean science at the graduate level.

LAURA ANDERSON: I get really defensive when I hear too much, uneducated ramblings about how the oceans are all dead, and all the fisheries are over-fished, and how we should stop all of these activities. And I’m one of the more aware people that I know about these issues, and I just don't believe that that's true.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: The future of local seafood in Oregon depends on balancing environmental and market imperatives, a task made all the more difficult during a global pandemic. But Laura thinks the past offers a powerful model of how to move forward.

LAURA ANDERSON: Look at our Dungeness crab fishery. We've been fishing it the same way for over 100 years. And the crab keep coming back year after year.

(snappy music)

All of these fishing families out here that we work with have children that they want to see be able to continue into the future, feeding people and harvesting, whether they just like the harvesting part or whether they really realize that this is about food security for a lot of us in a lot of ways and it’s a healthy way to feed the planet. I think about all of that and I have a lot of pride in it, and I feel privileged to be born into this, and I want to see that continue.

KAYTE YOUNG: This story by producer Josephine McRobbie and public Folklorist Joe O’Connell, features the voices of Oregon based commercial fishes and entrepreneurs. O'Connell conducted the original research in August 2019 for the Oregon Folklife Network with support from the National Endowment for the Arts. We were deeply saddened to learn that Amber Novelli who you just heard in this story and her husband Kyle Novelli lost their lives in a fishing accident on June 29th, 2020. Since this lost, Amber and Kyle's family have worked to keep operating Novelli's crab and seafood. Those wishing to support the family during this difficult time can find out how at Earth Eats dot org.

(Earth Eats theme music)

That's it for the show this week, the last show of the year. Thanks for listening and we'll see you in 2021. Take care.

RENEE REED: The Earth Eats team includes Eobon Binder, Spencer Bowman, Mark Chilla, Toby Foster, Abraham Hill, Payton Knobeloch, Josephine McRobbie, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week to Carl Ipsen, Rahul Shrivastav, Erin Carmen-Sweeny, Eric Pearson and Joe O'Connell.

RENEE REED: Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from the artists at Universal Productions Music. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey.