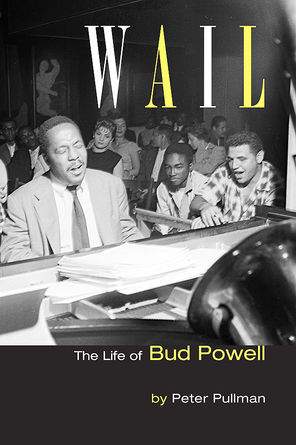

Acrobatic… elegant… dazzling… furious… torrential… fleet… daring… tirelessly inventive…beautiful… these are just some of the adjectives that you‘ll frequently encounter when you read about the piano-playing of Bud Powell. Powell‘s career on record spans from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s, but his influence has lasted far beyond his death at the age of 41 in 1966. As one writer put it, nobody conveyed the romantic agony of modern jazz more intensely than Bud Powell. What was it about Powell that made him such a compelling figure in the music‘s history? Peter Pullman, the author of Wail: The Life Of Bud Powell, joins Night Lights this week and next to discuss the pianist's story and the recordings that he made.

Beginnings Good And Bad

Born in 1924, Bud Powell grew up in New York City as a piano-playing prodigy, the son and brother of musically talented family members, influenced by both classical music and rising-star jazz pianists such as Fats Waller and Art Tatum. While other kids played outside, Powell stayed indoors and practiced religiously. It was, as Peter Pullman notes, a culturally-charged time for Powell to come of age, with the Harlem Renaissance in full flower during his childhood, and the dawn of modern jazz coming at the beginning of the 1940s during his teenage years, with artists such as Thelonious Monk and Charlie Parker exerting a strong influence on his development. He emerged in the middle of that decade as the leading pianist of the bebop movement, astonishing listeners and his fellow musicians with brilliant, high-speed improvisations of rhythmic and harmonic ingenuity.

But the personal troubles that would dog Powell throughout his career were emerging as well. Powell had first made his mark in the professional jazz world as a member of trumpeter and former Ellingtonian Cootie Williams' band, and it was while he was with Williams‘ band that he received a beating at the hands of Philadelphia police, the disorienting effects of which Williams and others marked as the beginning of the troubles that would afflict Powell for the rest of his life.

"Do People Remember Me?"

Still, Powell began to make his way impressively in the modern jazz scene that was emerging with such vitality in mid-1940s New York City, recording with other young musicians such as Dexter Gordon, Sonny Stitt, Kenny Clarke, and Max Roach. Though he also performed in nightclubs and on concert stages a number of times with Charlie Parker, the leading light of the modernists, Powell entered a recording studio with Parker on only one occasion, in May of 1947. We'll hear one of the resulting tracks, "Cheryl."

Bud Powell would not get a chance to lead his own recording date until 1949-after an altercation at a bar in late 1947, he was institutionalized, and spent almost all of 1948 off the jazz scene. Institutionalization, in its relatively crude and sometimes punitive late-1940s state, was not Powell‘s only problem--he had also begun to develop a destructive penchant for alcohol and other substances--but it was made even more difficult for Powell because of his race and his vocation, and it repeatedly removed him from the jazz scene during one of its most innovative and vital eras. Between November 1947 and February 1953--the period which many jazz critics consider to be Powell‘s peak as an artist--the pianist was institutionalized several times, spending what Peter Pullman has determined to be a little more than three years of that five-year period in psychiatric hospitals. When Marian McPartland came to visit him, he asked her, "Marian, do people remember me?"

"Let's Go, Let's Go!"

Whenever Powell did step into a recording studio during these years, it seemed as if musical miracles came to pass. One case in point is his first session for Blue Note Records in 1949, which featured bebop colleague Fats Navarro on trumpet, a teenage Sonny Rollins on saxophone, and three inventive Powell compositions, among them "Bouncing With Bud" and "Dance of the Infidels," both heard on this program.

Two years later Powell would wax one of his most impressive self-penned efforts for the Blue Note label as well, an epic-in-three-takes titled "Un Poco Loco," done after Powell went mysteriously missing from the studio and then rushed back in saying "Let‘s go, let‘s go!" Peter Pullman cites it as a landmark moment in Powell‘s musical career.

That same year Powell did another session for Norman Granz that gave listeners the chance to hear him at length in a solo piano setting--a musical context in which Powell seems to provide the missing bass and drum parts through his own playing. The session also brought forth more Powell originals, including a tune that Miles Davis‘ "Birth of the Cool" band recorded under the title "Budo" (we hear it on this program as "Hallucinations," along with another Powell composition performed as a solo piano piece, "Oblivion").

Off The Scene, Then On It Constantly

In the summer of 1951 Powell was arrested along with Thelonious Monk after police officers found drugs in the car in which they were sitting. A traumatic experience in New York‘s Tombs prison and a lengthy hospitalization followed, taking Powell off the scene for almost all of 1952.

Released from the hospital in early 1953, Powell began to play regularly at New York City‘s Birdland nightclub and lived in a small penthouse apartment, his life closely supervised by Birdland manager Oscar Goodstein. Goodstein has been portrayed as an exploitative figure in many accounts of Powell‘s life, but Peter Pullman says he played a supportive role as well, helping the pianist to tend to day-to-day matters of responsibility.

In the autumn of 1953 Powell turned 29. He continued to play nearly every night at Birdland, maintaining an exhausting work pace--brought about in part, Peter Pullman says, by Goodstein‘s desire to make good on his investment.

That pace proved to have a price, and Powell would pay for it for the rest of his career, as the shadows of fatigue and other desultory forces began to close in on him. We'll explore the consequences and the remaining 12 years of his career, including his five-year stay in Europe, on the next edition of Night Lights.

More Bud

Listen to The Scene Changes: The Life And Music Of Bud Powell, Part 2

Check out the previous Night Lights program, Burning With Bud: Bud Powell Live 1944-1953, which documents the pianist at his peak in a number of nightclub and concert settings.

Peter Pullman's Powell biography can be ordered at Wailthelifeofbudpowell.com. A Kindle edition is also available through Amazon.