Ricky Riccardi's latest Louis Armstrong book chronicles the trumpeter and singer's middle years and his ascent to cultural stardom.

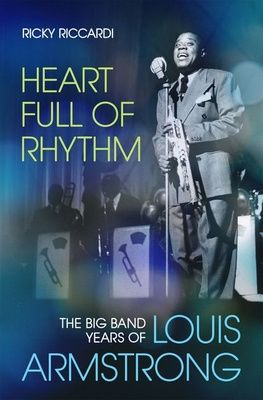

From 1929 to 1947 trumpeter and singer Louis Armstrong, who had already made a series of seminal small-group recordings that would become a cornerstone of jazz history, rose to popular culture stardom, appearing in movies, becoming the first African-American to host a weekly radio program, and waxing a wealth of material for Decca and other labels that brought him greater commercial success, as well as critical controversy. I’ll be featuring music from those years on this edition of Night Lights, and we’ll also hear from Armstrong biographer Ricky Riccardi, whose book Heart Full Of Rhythm chronicles this key but often overlooked stretch of Armstrong’s career.

(Louis Armstrong and Jack Teagarden in 1944 doing “Jack Armstrong Blues”)

In 1929 Louis Armstrong was 28, only a few years removed from his New Orleans hometown, a highly-accomplished jazz artist whose creative prowess as an improviser, both playing trumpet and singing, was already well-established. In particular, the recordings he made with a studio band called the Hot Fives and Sevens laid the groundwork for much of what would follow in modern jazz. Armstrong was not really yet what we’d consider to be a star, though; that would come about over the next 15 years. Jazz scholar and Louis Armstrong House Museum Director of Research Collections Ricky Riccardi, who previously chronicled the last twenty-five years of Armstrong’s life in his book What A Wonderful World, takes a look at what might be called the performer’s middle period in his book Heart Full Of Rhythm. It’s an era that Riccardi feels has often been unfairly maligned and overshadowed by Armstrong’s work in the 1920s:

Riccardi says there’s a bit of justification for this critical neglect, but that it’s ultimately far overshadowed by Armstrong’s accomplishments in these years:

Louis Armstrong’s 1929 recording of “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love,” which critics have cited not only as a prototype for Armstrong’s subsequent big-band era recordings, but for its influence on numerous other artists such as Bing Crosby and Ethel Waters as well. From now on this was the context in which Armstrong would be heard most often, backed by a larger ensemble, frequently both singing and playing trumpet, mixing hot jazz elements with influences that modern-day listeners might find surprising, like the saxophone sound of Guy Lombardo’s band. Ricky Riccardi points out that Armstrong was no stranger to such a musical setting—that in fact most of his work throughout the 1920s had been as a sideman with dance orchestras, and that the Hot Fives and Sevens, significant as they were, represented only a couple of weeks of studio time in the trumpeter’s career:

Louis Armstrong’s 1931 recording of Hoagy Carmichael and Mitchell Parrish’s “Stardust,” a recording so notable for Armstrong’s trumpet playing and creative vocal interpretation that nearly 70 years later filmmaker Ken Burns would select it to open his 20-hour documentary about the history of jazz. Armstrong’s star was beginning to rise beyond the immediate circles of the jazz world—and yet he remained a black man in a deeply racist and segregated society. Ricky Riccardi’s book Heart Full Of Rhythm describes some of the ongoing hostility that Armstrong encountered and his response:

Louis Armstrong’s 1933 RCA Victor recording of “I’ve Got A Right To Sing The Blues,” made just a couple of years before what we now call the swing or big band era got fully underway. Ricky Riccardi says Armstrong’s influence on that era was profound:

Louis Armstrong’s 1936 recording of “Swing That Music,” which was also the title of a memoir that Armstrong published that year—the first autobiography of a jazz artist, and another sign of Armstrong’s growing fame. The song was recorded for Jack Kapp’s Decca label, home to Bing Crosby, among others, and the company for which Armstrong would make the bulk of his recordings until the late 1950s. Armstrong’s Decca years would be controversial with critics, who were unhappy with the wide range of material he was given that frequently strayed far outside the aesthetic parameters of diehard jazz fans’ preferences, but which proved to be popular with listeners. Heard today, Armstrong’s Decca recordings offer a rich bounty of superlative trumpet and vocal performances. Ricky Riccardi thinks Armstrong’s Decca legacy is a testament to his remarkable versatility as a performer:

Louis Armstrong’s 1938 Decca recording of Hoagy Carmichael and Stanley Adams’ song “Jubilee.”

I’m featuring the music of Louis Armstrong on this edition of Night Lights, along with commentary from Armstrong biographer Ricky Riccardi, whose book Heart Full Of Rhythm tells the story of Armstrong’s so-called “middle period” from 1929 to 1947. Armstrong’s brilliance as a jazz artist was never in doubt; but his ability to sustain enduring success as a performer gained a key ally in these years:

Armstrong’s first two managers, Tommy Rockwell and Johnny Collins, proved problematic, though, helping to contribute to the dilemma Armstrong found himself in by 1935:

Glaser also played an important role in Armstrong’s popular culture elevation from the mid-1930s on:

In 1937 Armstrong became the first African-American to host a weekly radio program when singer Rudy Vallee took a 13-week break from his show, sponsored by Fleischmann’s Yeast:

Though Armstrong’s turn as host was undermined by weak and stereotyped comedic bits performed by the supporting cast, he looked back on it with pride. Four years later, when jazz critic and producer Leonard Feather put together a press release on Armstrong’s behalf, he asked Armstrong to list his most notable accomplishments. Armstrong ranked his 13-week radio-show host spell at the top. Ricky Riccardi, struck by that, also points to what he listed next, reflecting his recent time in Hollywood:

By the time the 1930s ended, Armstrong was being confronted with another challenge: his own musical past. Jazz was undergoing the first of its revival periods, with some critics and fans arguing that the music had been at its peak in the 1920s. Armstrong’s seminal recordings from those years, especially those made with the Hot Fives and Sevens, began to be reissued—and for the first time the artist found himself competing with his not inconsiderable legacy:

Louis Armstrong in 1938 revisiting one of his 1920s recordings, “Struttin’ With Some Barbeque.” Another recording from this era, made in 1939, unintentionally looks forward, cited by Ricky Riccardi in his book as making Armstrong sound “like the grandfather of hiphop… with a proto-rap vocal.” Here’s Louis Armstrong and “You’ve Got Me Voodooed,” on Night Lights:

Louis Armstrong and “You’ve Got Me Voodooed,” recorded for Decca in 1939, a period of continuing prolific activity for the performer. That activity would be slowed, though, in the next few years, by the conflagration of World War II, as Ricky Riccardi notes:

Louis Armstrong’s hit 1945 recording of “I Wonder,” a song written by soldier Cecil Gant that enjoyed popularity in the waning months of World War II. The end of that war ultimately proved to be a professional landscape-changing event for many in the big band world as popular culture underwent inevitable changes, and Armstrong’s big band would eventually fall by the wayside as well. After a highly successful small-group performance at Carnegie Hall in 1947, Armstrong would spend the rest of his career leading a downsized ensemble called the All-Stars, featuring much of the repertory of his early years. Though previous accounts have made the end of Armstrong’s big band seem inevitable, Ricky Riccardi doesn’t think it was necessarily a given:

MORE LOUIS ARMSTRONG ON NIGHT LIGHTS

It's All In The Game; Louis Armstrong 1947-1957

Satchmo, Take Two: Louis Armstrong At The Movies

OUTTAKES

(Special thanks to Ricky Riccardi)