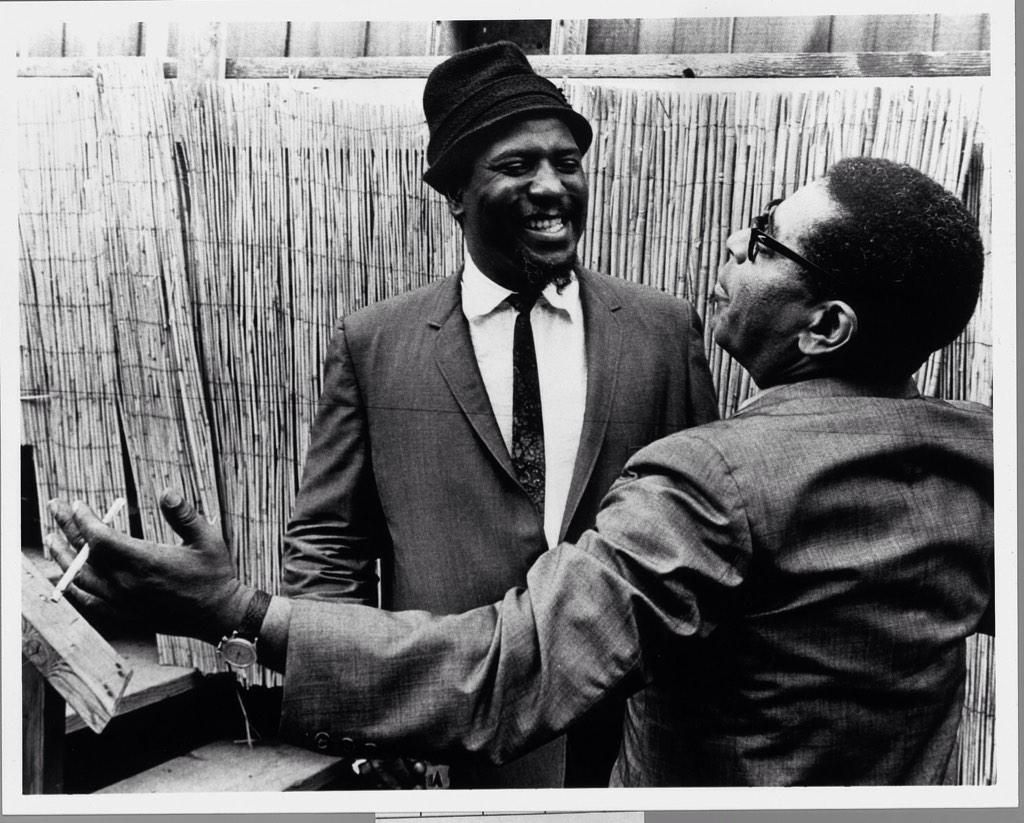

Pianist Thelonious Monk and trumpeter/presidential timber Dizzy Gillespie at the 1963 Monterey Jazz Festival.

In 1963 the Monterey Jazz Festival held its sixth annual September weekend concert series, which included the launch of Dizzy Gillespie’s presidential campaign, a Modern Jazz Quartet dedication to Martin Luther King Jr, the festival debuts of Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk, and what would prove to be one of Jack Teagarden’s final appearances. On this edition of Night Lights we’ll hear music from all of those artists and some of the historical context that surrounded their performances.

Here’s Dizzy Gillespie at the 1963 Monterey Jazz Festival introducing a song, including some banter with band member James Moody that invokes civil-rights icon Malcolm X and the changing terms of racial identification in the early 1960s:

In 1963 the Monterey Jazz Festival was in its sixth year, successfully established as an annual event that drew some of the most popular and acclaimed jazz acts around. Nearly 30,000 jazz fans descended on the central California coastal town in late September that year to see, among others, the Dave Brubeck Quartet, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie’s group, singer Carmen McRae, and Harry James’ big band. However, the 1963 festival, unlike most of its predecessors, did not garner glowing notices in its initial reviews. Music writer Ralph Gleason cited an excess of “dull and overly ambitious portions” and both he and DownBeat correspondent Don DeMichael bemoaned poor planning and cancellations, as well as a lack of newly-commissioned music, something for which Monterey had built a reputation.

In retrospect, though, Monterey 1963 was notable for several things—the festival debuts of Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, and Gerald Wilson’s big band, the rollout of Dizzy Gillespie’s only semi-humorous “Dizzy For President” campaign, one of jazz legend Jack Teagarden’s last major-venue appearances, and the Modern Jazz Quartet’s acknowledgement of Martin Luther King Jr., only several weeks removed from his “I have a dream” speech. The festival also brought together younger modern players and older jazz musicians; Miles Davis’ 17-year-old drummer Tony Williams sat in with a traditional-jazz trio led by 62-year-old banjo player Elmer Snowden, founder of the group that eventually became Duke Ellington’s orchestra, and baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan joined forces with trombonist Jack Teagarden, clarinetist Pee Wee Russell, and pianist Joe Sullivan for a set. I’ll start with an encounter from that performance, an improvised blues by Mulligan and Russell:

One of the highlights of Monterey 1963, singled out by both Ralph Gleason and DownBeat reviewer Don DeMichael, was the festival debut of pianist Thelonious Monk’s quartet. Monk’s star was still on the rise; he had begun to record for a major label, Columbia Records, and he would soon appear on the cover of Time Magazine. Gleason and DeMichael each praised the musical intensity of the Monk quartet’s performances, and DeMichael added appreciation for Monk’s own offbeat brand of showmanship: “He came onstage in topcoat and hat, and in the middle of the first tune wandered around during Charlie Rouse’s solo, obviously looking for something. He dashed off the stage, reappeared, spotted an unused microphone stand, took off his coat, and casually hung it on the stand.”

Another notable artist made his debut at the Monterey Jazz Festival that year—trumpeter Miles Davis, who was emerging from a transitional period of personnel changes in his band. The nucleus of what would come to be known as Davis’ “Second Great Quintet” had started to come together in 1963, with a rhythm section comprised of 23-year-old pianist Herbie Hancock, the 26-year-old bassist Ron Carter, and the 17-year-old drummer Tony Williams. Tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter would soon provide the final piece of that quintet, but at Monterey George Coleman was still Miles’ front-line horn partner. “You have to learn to close your ears and wait for the good things,” Ralph Gleason quoted Miles as saying backstage, and with this band good things had obviously begun to arrive. Here they are doing a brisk-tempo version of one of the compositions from Davis’ landmark album Kind Of Blue:

While Davis made his Monterey debut in 1963, fellow trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie was by now a mainstay of the annual event, marking his fourth appearance in six years. This autumn the popular trumpeter had politics as well as jazz on his mind, launching his “Dizzy For President” campaign. The campaign had its roots in promotional buttons that Gillespie’s booking agency had made years before, and more recently in jazz writer Ralph Gleason’s attempt to counteract what he saw as the reactionary nature of senator Barry Goldwater’s presidential run with an entertaining and pro-civil-rights perspective by getting Gillespie on the ballot in California. Eventually chapters supporting Gillespie’s run would spring up in 25 states, and though he ultimately failed to appear on any ballots, the national jazz press covered his pronouncements and potential Cabinet picks, including Duke Ellington as minister of state and Max Roach as minister of defense. While there was a good deal of humor in Gillespie’s run, he also donated money from sales of his campaign buttons to civil-rights organizations and spoke out against segregation and in favor of world disarmament.

At Monterey the trumpeter spent an afternoon volunteering at a booth that was raising funds to help the NAACP. Don DeMichael’s DownBeat roundup offered the following description of Gillespie’s entrance for his evening performance, including a rare glimpse of onstage levity from Miles Davis: “The Gillespie quintet’s set began with the unexpected appearance of Miles Davis and Harry James carrying Gillespie’s tilted trumpet and looking about the stage for its owner, who soon strolled in nonchalantly. After some horseplay among the three trumpeters, Davis posed in leering fashion, a cigarette holder jauntily angled from his mouth, much to the delight of the audience, photographers, and Gillespie, who announced, ‘I’m dumbfounded, not to say enthralled.’” Near the end of Gillespie’s set, he brought on vocalist Jon Hendricks, who helped him turn the bop-era standard “Salt Peanuts” into a musical call to action for Gillespie’s presidential campaign:

Gillespie’s “Dizzy For President” campaign launched in the shadow of recent momentous and volatile events in America. Civil rights leader Medgar Evers had been murdered in Mississippi earlier that summer. Just three weeks prior to the festival, Martin Luther King Jr. had delivered his “I have a dream” speech at the March on Washington. Five days before the start of the festival, four African American girls had been killed when white supremacists bombed a church in Birmingham, Alabama. At one point Jon Hendricks asked the crowd to observe a moment of silence for the dead children. Modern Jazz Quartet pianist and Monterey Jazz Festival music director John Lewis surely had these things in mind when he introduced the MJQ’s performance of his composition “The Sheriff” with a dedication to Martin Luther King Jr.—perhaps invoking the title in mind of the law-enforcement officials King and the civil-rights movement were facing off against in the South. The Modern Jazz Quartet, live at Monterey in 1963, on Night Lights:

I close out this edition of Night Lights with a festival performance of "A Hundred Years From Today" by Jack Teagarden. The trombonist and vocalist had recently turned 58, and his Monterey appearance as an amiable representative of jazz’s old guard was a poignant family affair, reuniting him onstage with his piano-playing mother and sister, as well as his trumpet-playing brother. Teagarden was in difficult straits; he was having trouble getting gigs, he’d recently separated from his wife, and he'd begun to drink again after years of sobriety. Four months after Monterey he would pass away in a New Orleans hotel room; the festival proved to be the final highlight of an illustrious career:

MORE MONTEREY JAZZ FESTIVAL ON NIGHT LIGHTS:

Jazz From Monterey, 1958: Birth Of A Festival

... and here's more about Dizzy Gillespie's 1964 presidential campaign.