Max Roach was an iconic drummer and civil-rights activist whose innovative career opened in the bebop era and extended to the end of the 20th century.

At the dawn of the 1960s drummer Max Roach was already well-established as an innovative and influential musician. As the decade progressed Roach would be at the forefront of the convergence of jazz and the civil-rights movement, and the music he made on albums such as The Freedom Now Suite would reflect his outspoken activism on behalf of liberation causes both at home in America and abroad in Africa. On this edition of Night Lights we’ll explore that music and Roach’s participation in a turbulent decade of long-lasting impact.

If Max Roach’s career had ended in 1960, the then-36-year-old drummer’s place in jazz history would have already been secure. Born in North Carolina in January 1924, Roach had grown up in Brooklyn after his family moved north when he was four years old, and in the 1940s had become one of the most innovative and important musicians on the burgeoning bebop scene, working with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Miles Davis, and many other notable contemporaries. Like his compatriot Kenny Clarke, Roach expanded the rhythmic and melodic range of the drums’ role in jazz; fellow drummer Stan Levey said “I came to realize that because of him, drumming was no longer just time, it was music.” Roach had gone on to co-found the pioneering DIY record label Debut with fellow Black jazz artist Charles Mingus, and to co-lead a group with trumpeter Clifford Brown that begat some of the finest hardbop jazz recordings of the 1950s. His 1957 album Jazz In 3/4 Time broke away from jazz’s orthodox 4/4 time signatures two years before Dave Brubeck did the same with his album Time Out.

But more of Roach’s most memorable work was still in front of him as the 1960s opened. He increasingly worked with his partner, the singer Abbey Lincoln, and began to put his longstanding interest in civil-rights activism at the forefront of his music. In 1960 he and Charles Mingus staged an alternative concert to the Newport Jazz Festival, in protest of the festival’s artist presentation choices and compensation. Roach and Black singer and songwriter Oscar Brown Jr. also sped up their development of an extended work that had originally been intended for the 1963 centennial celebration of the Emancipation Proclamation. Inspired by the sit-ins that Black students in the South had begun at segregated restaurants in the early months of 1960, Roach and Brown’s We Insist! The Freedom Now Suite became a landmark musical statement about racial oppression in the past and in the present, with Abbey Lincoln playing a prominent role in the sound of the album. “Triptych: Prayer/Protest/Peace” was a Lincoln & Roach duo feature, with Lincoln’s wordless vocals spiraling into anguished rage in the middle part, while “Freedom Day” paid tribute to the Civil-War era emancipation of slaves.

Roach’s next album, recorded for the Impulse label in 1961, continued his emphasis on civil-rights themes in his music and further nods to the growing anti-colonial Pan African liberation movements in Africa. Percussion Bitter Sweet included tributes to the early-20th century black nationalist figure Marcus Garvey, as well as pieces dedicated to women and young people in freedom and independence movements, and to those who had died fighting for such causes. On the album’s concluding track, Roach saluted the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. “The artist should reflect the tempo of his time,” Roach said in the album’s liner notes. “He should also endeavor to bring about changes where possible. The newspapers are filled with cries for freedom from every corner of the world.” Featuring Eric Dolphy on alto sax and Julian Priester on trombone, here’s Max Roach’s “Man From South Africa,” on Night Lights:

In 1962 Roach and Abbey Lincoln got married. They also participated with fellow musicians Don Ellis and Lalo Schifrin and several white jazz writers in a no-holds-barred DownBeat Magazine round-table discussion titled “Racial Prejudice in Jazz.” One of the writers, Ira Gitler, had given Lincoln’s recent album Straight Ahead, on which Roach played, a lukewarm review in DownBeat that criticized Lincoln’s invocation of civil rights causes and labeled her a “professional Negro.” Roach vigorously pushed back against Gitler’s explanation that Lincoln was “exploiting” her racial identity for her music, saying “Who knows more about the Negro than the Negro? If anybody has the right to exploit the Negro, it’s the Negro. Everybody else up until this point has been exploiting the Negro. And the minute the Negro begins to exploit himself… here comes somebody who says they shouldn’t exploit themselves… Here’s the point: she has a perfect right to exploit the Negro.” The ensuing discussion reflected the rising tensions of the early 1960s, as Black leaders such as Malcolm X began to express and advocate stronger responses to the persistence of racism in America.

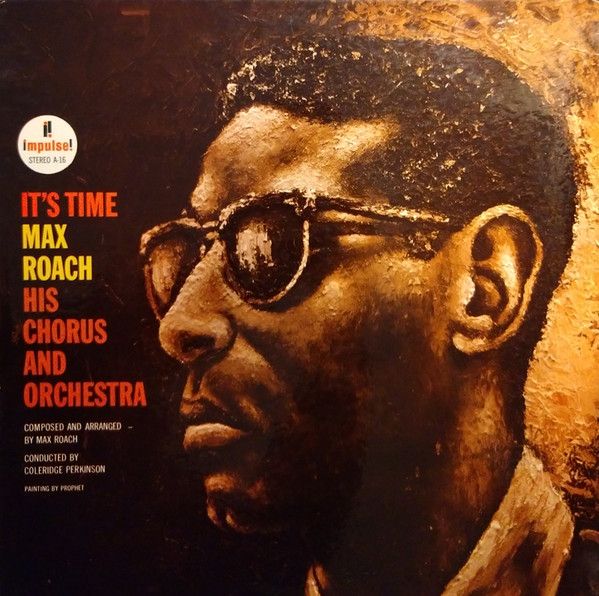

That same year Roach also recorded an innovative follow-up album for the Impulse label, employing a vocal chorus. “The voice, as an instrument, has always fascinated me,” he wrote the liner notes. “The abundance of variations the voice can use in changing the color of one note are infinite. It was with these tonal images in mind that led me to prepare the album.” Max Roach and the title track from his album It's Time, on Night Lights:

In addition to the classic civil-rights themed albums that Roach made in the 1960s, he also waxed two notable piano-trio albums. One featured a little-known Philadelphia pianist, Hasaan Ibn Ali, who spun his own musical brew from influences such as Thelonious Monk and Elmo Hope, and whose album with Roach was his only known-to-be-recorded outing until recent years, when new discoveries garnered him a wider following among 21st century jazz fans. The other was with old friend Charles Mingus and their much respected elder, jazz giant Duke Ellington—a combination that apparently became rather volatile during the recording sessions, with Mingus walking out at one point after saying he could no longer play with Roach. The musical results, however, proved to be a modernistic small-date highlight in the later Ellington discography. Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach doing “A Little Max,” on Night Lights:

Now we’re going to hear Max Roach unadorned, in a solo setting from his 1966 album Drums Unlimited that shows Roach, twenty years on from his innovative contributions to the bebop movement, keeping time with younger drummers on the avant-garde scene of the 1960s. Jazz writers Richard Cook and Brian Morton describe Roach’s title track performance as “a meticulously structured and executed essay in rhythmic polyvalence that puts Sunny Murray and Andrew Cyrille’s more ambitious works in context.” Max Roach and “Drums Unlimited,” on Night Lights:

In 1968 Roach made his final studio date of the decade, employing younger musicians such as saxophonist Gary Bartz and trumpeter Charles Tolliver to record what is now considered to be one of his finest small-group albums. Changes were on the horizon for Roach: in 1970 his and Abbey Lincoln’s marriage would end, and he would found the percussion ensemble M’Boom. For the rest of his life Roach would continue to explore different musical contexts in which to express himself—and while he continued to espouse and pursue his activist goals, in his life and in his music, the 1960s would remain a high point for the convergence of his politics and his art. I’ll close with Max Roach and the title track from his 1968 album Members, Don't Git Weary, on Night Lights:

Previously on Night Lights

We Shall Overcome: Civil Rights Jazz

1962, The Year In Jazz: Cool In Crisis

Portrait Of Max: Max Roach 1924-2007