Richard Oswald's family has been farming in northwest Missouri since the 1840s. In his lifetime, he has experienced the effects of climate change firsthand, from warmer seasons to catastrophic flooding. "I just feel that if we had open discussions about it, then we could be better prepared for what happens,” Oswald said. (Shahla Farzan / For Harvest Public Media)

When Richard Oswald was growing up in northwestern Missouri in the 1950s, his dad had a firm rule: don’t plant corn until mid-May, when the first oak leaves of spring are the size of squirrels’ ears.

But that rule has become a relic of the past. In Rock Port, a small farming community near the Nebraska border, the growing season now begins more than a month earlier.

“If ground conditions permit it, a lot of people will plant the first of April here,” Oswald said. “When I was a kid, you would have never done that.”

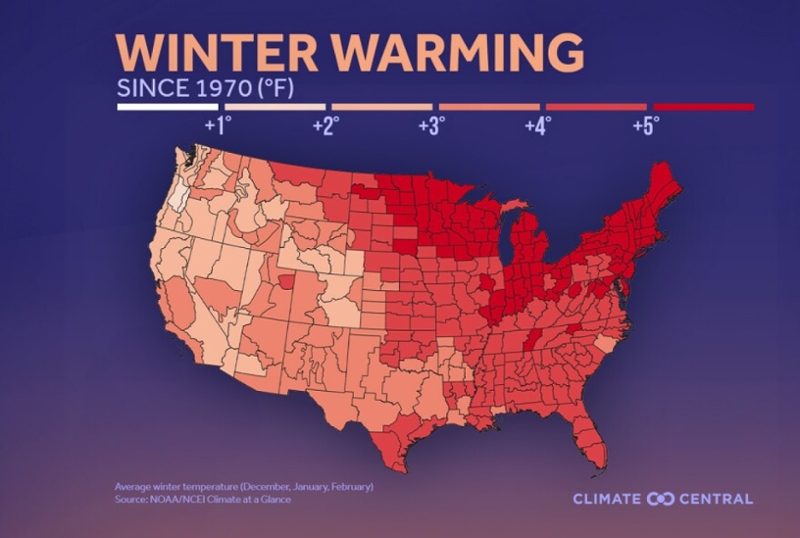

Across much of the U.S., winter is not as cold as it used to be. The four warmest Januaries on record have all occurred since 2016, a harbinger of things to come as climate change worsens. In Missouri, Iowa, Nebraska and several other states, winters are about four degrees hotter on average than in 1970 — and farmers are starting to feel the effects.

As the planet continues to warm, cold winter weather will become less and less common, said Amy Butler, a research scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration who studies climate variability.

“Less cold does not mean never cold, it just means that really cold weather will happen less often and be less severe or persistent in the future,” said Butler.

Soaring wintertime temperatures made headlines in January, after another study found most major cities worldwide will be too warm to host the Winter Olympic Games by 2080. But for industries that are highly dependent on weather conditions, such as agriculture, climate change is already causing a cascade of ripple effects.

Milder winters and agriculture

Midwestern soil is fertile because it typically freezes in the wintertime, halting microbes and other organisms that break down organic matter. But as winters get warmer, soils remain unfrozen for longer periods of time and begin to lose nutrient value.

Warmer winters also mean precipitation is more likely to fall as rain rather than snow, which can quickly saturate the ground and create muddy conditions, said Dennis Todey, director of the USDA Midwest Climate Hub in Ames, Iowa.

“When you have soils that are very wet and you're trying to plant or move manure around, just the weight of equipment will press the soil down and cause soil compaction,” Todey said.

Compacted soil becomes like concrete, making it much harder for roots to grow.

Milder temperatures may also help certain pests survive the winter and in some cases, expand into the upper Midwest. The corn earworm, a widespread crop pest in the southern U.S., is expected to move northward into Iowa, Nebraska and South Dakota as the climate warms.

“As we have warmer winters or shorter cold periods, some of these insects may be able to overwinter here,” Todey said. “Or, instead of having to overwinter in Texas, they overwinter in Arkansas. That's a shorter distance they have to be reintroduced when it comes to the next growing season.”

While longer growing seasons can lead to increased yields in the short-term, researchers say climate change will negatively affect agriculture in Missouri.

When it comes to crop production, Missouri “will be the hardest hit of Midwestern states,” according to a 2020 University of Missouri report. Corn yields in Missouri are expected to decline over the next several decades, the report finds, with production “almost sure to cease by the middle of the century.”

Rising costs of climate change

Farmers in the Midwest are already coping with a range of climate change-driven impacts that go well beyond warmer winters.

In the past decade, Liz Graznak’s organic vegetable farm near Columbia, Missouri has weathered increasingly extreme swings in weather.

“We don't get a couple of inches of snow; we get 18 inches of snow all at once and then in five days, it's 70 degrees again,” Graznak said. “We don't get a couple of inches of rain; we get a 12 inch downpour in the span of 24 hours. That's devastating to a vegetable farm.”

Rising global temperatures are driving more extreme weather events, including heat waves, heavy rains and floods.

To help protect her crops, Graznak has built four large greenhouses on her property in just over a decade. Inside, she’s able to grow delicate, high-value crops, including flowers, lettuce and spinach.

In one greenhouse, nicknamed Goliath, rows of tiny delphinium sprouts poke out of the soil, cocooned under layers of cloth. By May, the stalks of blue and purple flowers will be ready to sell at the farmer’s market.

But these greenhouses come at a steep cost. Nearly seven years ago, Graznak spent more than $18,000 to build Goliath — and since then, the price has more than doubled.

“When I think about these costs, in my brain, I say, ‘Okay, how many heads of lettuce is that?’” she said. “I know I can sell a head of lettuce for $4, so how many heads of lettuce do I have to sell to be able to pay for that greenhouse? And that’s a lot of lettuce.”

Still, as the climate continues to change, Graznak expects she’ll likely have to rely on greenhouses even more.

“I’m already thinking about the things I need to do: putting up more greenhouses, growing under more plastic, cutting out certain crops,” she said. “I think all farmers, if they’re successful, are constantly thinking about that.”

Difficult to discuss

Nearly 250 miles away, Richard Oswald is also seeing the effects of climate change firsthand on his farm in northwestern Missouri.

Oswald has deep roots in the community. His family has been farming this land since the 1840s, when his great-great grandfather Enoch Scamman traveled to Missouri from Maine by covered wagon.

Though short cold snaps still punctuate the winters, Oswald said, average temperatures have been creeping up every year.

Climate change has been on his mind more and more since 2019, when catastrophic flooding swamped his farm and childhood home. His land was engulfed in murky water from the Missouri River for months, accessible only by boat.

“From the Nebraska bluffs behind us to the Missouri bluffs in front of us, it was all water,” Oswald said, sweeping his hand across the horizon.

He lost roughly 26,000 bushels of corn in the flood, after five grain bins collapsed into twisted heaps of metal. The white 1930s farmhouse where he was born and lived for most of his life has since fallen into disrepair, a faint line of mildew on the siding left behind from the floodwater.

Oswald worries that climate change is going to make farming much more difficult in the future, especially for smaller producers with slim profit margins.

But in his community, few will discuss it.

“Everything a farmer does is based on science,” Oswald said. “And yet, I know a lot of farmers who just turn their back on science when they start talking about these political issues. I just feel that if we had open discussions about it, then we could be better prepared for what happens.”