KAYTE YOUNG: From WFU in Bloomington, Indiana, I'm Kayte Young. This is Earth Eats.

JESSICA WILSON: Speaking directly to black women and wanting black women to know that their bodies are not the problem. The way that our bodies are treated and problematized and pathologized, we're often taught that it's our fault, that it's our problem to fix or we just need to love our bodies out of societal oppression.

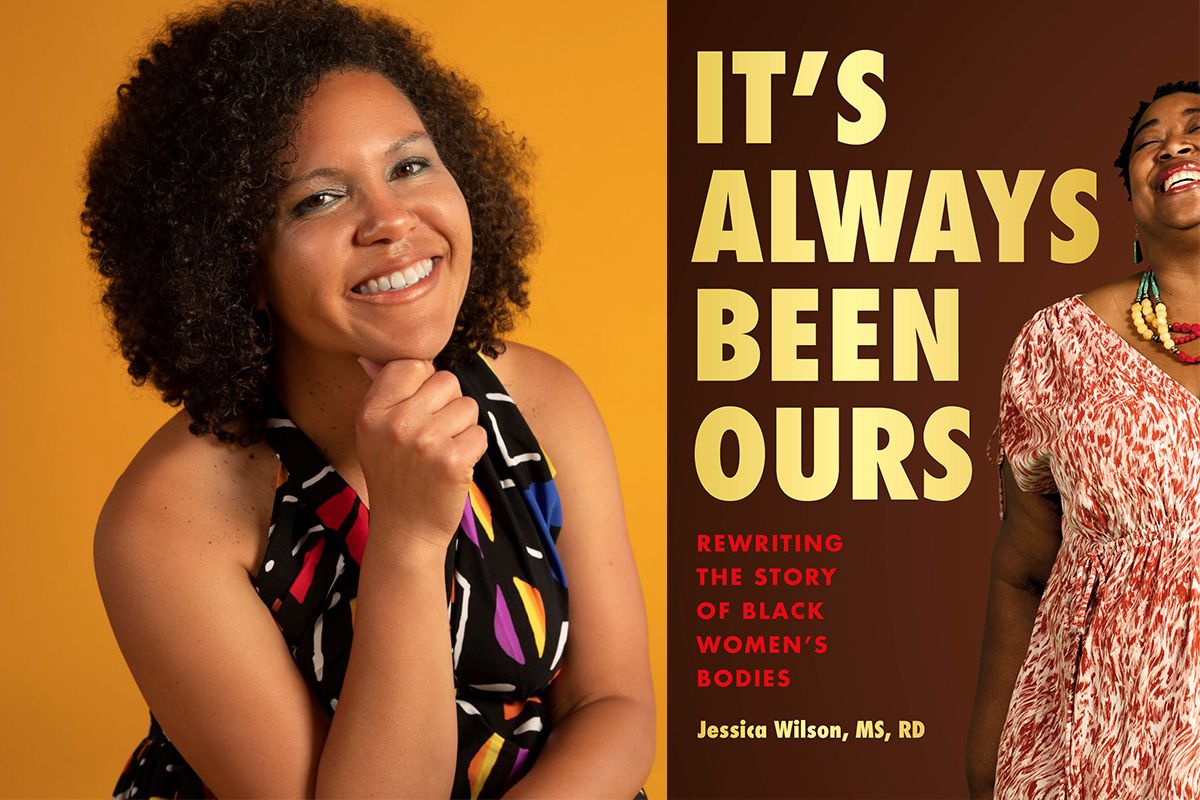

KAYTE YOUNG: This week on the show, a conversation with dietitian and author, Jessica Wilson about her book 'It's always been ours'. Re-writing the story of black women's bodies. Her book challenges us to rethink the politics of body positivity by centering the bodies of black women in our discussions about food, weight, health and wellness.

KAYTE YOUNG: That conversation's just ahead. Stay with us.

KAYTE YOUNG: The American Academy of Pediatrics released in February of 2023, new guidelines for health care providers for addressing childhood obesity. The guidelines include aggressive interventions for controlling weight in children as young as two years old through adolescence.

KAYTE YOUNG: There's been a great deal of discussion over the past ten or 15 years about the dangers of obesity. There's been less information about the health risks caused by restrictive diets and eating disorders, and about the damaging effects of weight stigma. I want to have a conversation about the complexities surrounding weight, diet culture and about the racialized roots of our collective obsession with thin bodies.

KAYTE YOUNG: So I invited Jessica Wilson to Earth Eats. She's a dietitian, consultant and story teller and she's the author of 'It's always been ours, rewriting the story of black women's bodies', released in February of 2023. I started by asking Jessica to tell the story of how she ended up in the field of dietetics.

JESSICA WILSON: It starts back when I was four years old. I was a kid who was at the top of the growth curve and, you know, as a kid that seems like winning, but that was too big for books in the medical field and they really wanted me to have a smaller body. So at age six I was sent to a dietitian and, I was told to eat less and exercise more as a six year old and I don't remember much of it. All I remember is like being hyper focused on my food and body through childhood and then less so in high school, but still like those memories imprinted and when somebody was going through the list of professions that I could have, dietitian was one of them. So like I know what that is, sure, I'll be that and then through undergrad, I was definitely the only black student in my dietetics program. I was the only black person in my internship, my dietetic internship and then also in grad school to be perfectly honest.

KAYTE YOUNG: Wow.

JESSICA WILSON: Yes. It's wild, and then I got into working with eating disorders because I got a job at a health center and I had not gone into the field to work with people who didn't eat food. I wanted to work with people who ate food and then all of a sudden I'm working with people who aren't eating food and they taught us nothing about eating disorders in school. They thought it was only a therapist thing and so it was like a very, very steep learning curve. I was probably not great at it unfortunately for my patients for the first couple of years.

JESSICA WILSON: Black dietitians are like three percentish of the field, but they were not in California. I didn't know another black dietitian personally until 2020.

KAYTE YOUNG: You are the author of 'It's always been ours, rewriting the story of black women's bodies'. Could you start by telling us about what brought you to write this book.

JESSICA WILSON: Sure. There's two answers to that. The first one is, I didn't want to write the book, I said no many times to the editor who asked me to write it. And so in that process I was talking to a friend of mine and the pros and cons were I could reach more people than I do on my one on one practice. So one on one stuff is great but if I write a book I will be able to reach more people, more clinicians who are then talking to their patients about the same thing. So that was how I decided to write the book and reach more than just that one on one relationship.

KAYTE YOUNG: What was your goal in putting this out there?

JESSICA WILSON: That's a great question. It's multifaceted. So one was speaking directly to black women and wanting black women to know that their bodies are not the problem. The way that our bodies and treated and problematized and pathologized by the medical field, by society. You know, we're often taught that it's our fault, that's our problem to fix or we just need to love our bodies out of societal oppression. But I wrote the book for us to recognize that these influences are centuries in the making. Even in the medical fields it's designed to be a racist field in the first place. So that was one, and then for clinicians for sure to be able to care for and treat their clients clinically in a way that was culturally relevant.

KAYTE YOUNG: Personal narratives are woven throughout the book and that includes your own stories. Stories of some well known public figures and also the stories of people that you've worked with in your practice, and these stories allow you to illustrate the issues that you're identifying in the book and in the introduction you talk about a client who you call Mia. Her story in a way for me was unexpected, just in some of the details, and you just do so much work in that section to bring forward many of the problems that you're addressing in the book. I was wondering if we could just talk about her story for a moment.

JESSICA WILSON: Sure.

KAYTE YOUNG: Her story kind of starts out with the term that you use is the pathologizing of bodies and seeing your body as a risk factor. That was something that happened to her and it caused her to go on a diet, to lose a lot of weight and start exercising excessively, and then she had success with weight loss, and then she came to you. What did she present when she came to you?

JESSICA WILSON: First when she came in she was just looking for supplements. So she had gone to her new doctor after the previous doctor had given her the directive to lose weight. The newer doctor was curious about, you know, Mia's health generally and so did some lab tests and found that her lab work was showing signs of malnutrition, and so she came to me after getting that information and figured it was just something that supplements could cure. Her hair had been falling out and all she needed from me was a list of recommendations for supplements and that would cure the malnutrition. There had to be like a fruit or vegetable that she wasn't getting enough of, and that fruits and vegetables will not solve starvation restriction. That was the only thing that she was interested in.

KAYTE YOUNG: So many things come up in that one story, issues of the way that wellness gets sort of equated with purity and morality. Could you talk about that?

JESSICA WILSON: Yes. So Mia was on her wellness journey. It wasn't about weight loss, for her it was about just being really better and being accepted into an all white grad program. She didn't see it as a drive for thinness at all, she just wanted to be like well in her body. And as I discuss in the book, as she shrank, as she became smaller as a black woman in an all white grad program, she was finally treated well.

JESSICA WILSON: So black women are inherently too much yet not enough, hyper visible but invisible. So with her weight loss she was able to gain more social capital and also with the intersections of purity culture, she was able to give up all these things and feel better about herself. So often in society, it's the giving up, the withholding, you're doing basically, it used to be God's work and the withholding and avoidance of pleasure and avoidance of hedonism is inherently linked with religion and, you know, she was able to engage in wellness and purity and feel a lot better about herself, for doing these things and performing these rituals.

KAYTE YOUNG: I think that's just one of the most trickiest parts about restrictive diets or eating disorders is that, you know, when you're at your worst you're getting positive feedback from the culture around you. While it was allowing some social acceptance, she was also forgoing social connection in order to stay with the restrictive diet, and not avoiding her family but avoiding the family connection that happens when we share food from our traditions and from our families.

JESSICA WILSON: Yes, definitely. The increase in social capital, but then having to go the gym during those social times or what would be social times or, you know, not being able to eat anything at happy hour, so maybe skipping it altogether. Just pulling away from the family in general and having folks notice that she is bringing her own food to what used to be a shared meal. Those are things that people notice and that puts distance between family, between colleagues and friends when all of those things are happening.

KAYTE YOUNG: You also talk about how what you were recommending wasn't what she wanted to hear.

JESSICA WILSON: Yes. That is the hardest part of my work. I cannot solve the societal reasons that folks in general, especially black women are called to shrink our bodies. It just is not something that is solved in a dietitian visit. And even she understood what I was saying, and was very interested in the history of the pathologizing and problematizing of black women's bodies. But even knowing that, she was not open to giving up the increase in social capital. She needed to build connections and networks and the way to doing that as she had seen is to be more palatable in that environment. It's very sad, but also the reality. So me just asking her to eat more or saying she has an eating disorder, that's not going to matter because society is not going to change

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes. I could understand how it would have felt to have you say, you need to eat more and exercise less. That is just the opposite message and she's like, wait a minute, I'm healthy.

JESSICA WILSON: Yes. I'm on my journey and healthy.

KAYTE YOUNG: It's the healthiest I've ever been.

JESSICA WILSON: Yes. This is the best thing I've experienced, and also she felt good about herself and I find that way with a lot of people, they want to be perceived as working hard. So even if and when they're starving, people can see me losing this weight, they know that I'm a hard worker. All this stuff that we assign to weight loss and body stuff, it's just wild.

KAYTE YOUNG: You also point out that for her it wasn't about being a particular size, it was about survival, and I was really struck by the line where she says something about, she wants to lose even a little bit more weight to be safe, and I just thought the word safe.

JESSICA WILSON: Yes. It fit quite well in the storyline that she wanted to lose additional weight to be safe, but it was just a natural thing for her to say.

KAYTE YOUNG: There was just another thing in the introduction that I was really blown away by. You make a point about how in your training, Southern food was so vilified in your training as a dietitian. You write, Southern food is constantly vilified by dietitians and directly associated with black people. At the same time, hipsters and gentrifiers are enjoying a renaissance of ribs, pork belly, greens, ocra, mac and cheese, chicken and waffles and cornbread, when the same foods that are pathologized in the context of blackness are associated with thin white affluent people, they become a foodies gastronomical paradise.

JESSICA WILSON: That I saw living in Oakland. It was pretty quickly gentrifying when I was there and it was like this whip lash of, wait a second. In what were black neighborhoods and were becoming white neighborhoods, the same foods that had been like associated negatively in black quote neighborhoods was like still fancier in what was becoming white neighborhoods.

KAYTE YOUNG: I mean, it just kind of shows how it's really not about the food.

JESSICA WILSON: Right? It's not.

KAYTE YOUNG: So you use the word caste rather than race when you're talking about the effects of white supremacy. Can you explain why you made that choice for this book?

JESSICA WILSON: Yes. That distinction was laid out really clear for me and Isabel Wilkerson's book, Caste, and it made more sense here for me to use that one because in the land and world of diversity, equity and inclusion programs within work places and organizations, racism is always this interpersonal situation, right. And I can out learn myself or learn myself out of racism and that's how I saw things applied. There were Robin DiAngelo's, White Fragility and it was all about these ways that I feel, or ways that people feel and it was not. This is not about how people feel, it's about how the world has organized, everything that is at the foundation of this country, and we can't out think ourselves. We can't just change our behavior in order for these things to go away, they're embedded for us.

KAYTE YOUNG: Right, so it puts it more in the structural realm.

JESSICA WILSON: Yes, the systems and structures.

KAYTE YOUNG: My guest is Jessica Wilson. She's a Dietitian Consultant and story teller and the author of, 'It's always been ours, rewriting the story of black women's bodies', released in February of 2023. We'll be back with more from our conversation after a short break. Stay with us.

KAYTE YOUNG: Earth Eats. This is Kayte Young. I'm speaking with Jessica Wilson about her book, 'It's always been ours'.

KAYTE YOUNG: One of the things I was surprised to find in her book is the critique of the body positivity movement. I asked her how she would characterize that and what she sees as problematic.

JESSICA WILSON: I referred to the, like fluffy individual solutions to societal problems, is like a live, love, laugh. If only we can think ourselves into a more positive state of mind, whether it be bodies or food then we're going to be fine. But again, it's an individual solution. Thin white folks can think themselves into being fine with their bodies perhaps, but even if black folks, trans folks, folks with larger bodies, even if we feel better about ourselves, society is not going to feel better about our bodies. And in body positivity, the onus is on the individual one to do the work which is possible again for some folks to do and impossible for others. And then two, only addresses, again, that individual and how they feel, not the societal structures.

KAYTE YOUNG: People in the body positivity world often point to diet culture as the problem and you take issue with that. Can you talk a little bit about that?

JESSICA WILSON: Yes. I think it goes back to Mia as a great example. She wasn't trying to be thin. She didn't identify as reaching for the thin ideal, it was about that safety. And diet culture is inherently tied to our race based caste system, because in the 1700s and 1800s, people, especially white males, were defining both what health looked like, what a moral and good citizen looked like, and those were thin, white folks. Because what was unhealthy and a poor citizen, were black people, and they inherently tied fatness with blackness, based on one black woman that they had taken and trafficked, who was a large black woman, especially the size of her buttocks. So that inherently just painted blackness as hedonistic, as glutenous forever. And so when we look at a drive for thinness say, we can see that as a drive away from blackness and anti blackness.

JESSICA WILSON: We can position or say like racism is at the root of diet culture, but I re-frame it to say that whiteness, white supremacy is the actual driving force behind people wanting to be thin. So it's not actually diet culture, it's not Weight Watchers or WW now, or Jenny Craig. It is histories of association with fatness, with gluttony and blackness, and so it's really that connection that's making folks want to shrink our bodies.

KAYTE YOUNG: It's a really powerful thing to point out I think, and I know that it's a new concept for some people, maybe not for others. I know that the first time I heard that I was kind of like, oh, that's what's going on and of course felt so implicated in it. I have participated in it.

KAYTE YOUNG: So you talk in the book about the field of dietetics and eating disorders and about how white centered it is. You tell a story about the push back that you received from some of your colleagues when you were trying to talk about Eric Garner and the intersection of fatness and blackness. Could you talk about that, what happened there?

JESSICA WILSON: Yes. I was in the health and resize movement, which was a movement focused on weight stigma and the connection, or the lack of direction connection between weight and health. So the folks in the health and resize community were really looking at somebody who is physically active, if they're eating fruits and vegetables, then they can be just as healthy as thin people and the doctors will believe this. I was in those communities and I was not hearing people talk about how even if people are treated well for being larger, black people, brown people still need to go to the doctor's office. And when we go there we're not believed, we're a pain, we're not believed for our systems. So how can we connect fatness, blackness, brownness identity in this conversation? Can we have a more complex conversation? I was told, no, this is only about fatness, about folks who weigh more and have a higher BMI.

JESSICA WILSON: We're not talking about those other issues, that's for something else. That was a great moment for me to exit because, if folks weren't able to have an intersectional conversation about bodies, then I just needed to find my own take and leave that one.

KAYTE YOUNG: You talked about when black people going to the doctor, they're not being believed, their systems aren't being treated and I know that that's just true for people who are overweight too. That it's just like, well the only thing we're going to talk about is your weight, no matter what you're presenting with and it just sounds like it's doubly true for people of color.

JESSICA WILSON: Yes. So black women are still going to die during pregnancy or right after pregnancy, at far greater rates than both in white women and fat white women. So it is like this double overlapping identity for black folks and yes, absolutely, for fat folks who go to the doctor if their BMI is over either 25 or 30, whatever the problem is will be solved with weight loss. And being believed that you have any other pain or any other condition, a requirement is to lose weight first and then we can take you seriously, for sure.

KAYTE YOUNG: Jjust to clarify, how did you see that issue showing up in the case of Eric Garner.

JESSICA WILSON: He was policed both for his fatness and his blackness. He was surveilled and over policed because he was black, and then his death was not ruled to be a homicide at the hands of police because he was fat and if he wasn't fat, then he would have been able to breathe. So yes, the double edged sword I guess for that one.

KAYTE YOUNG: I wanted to talk about resilience and how resilience is often celebrated as a virtue, and black women are often put on a pedestal. Or as you put it in the book, seen as special aliens who can heal the world. Could you talk about that and what is so harmful about that notion. It sounds so positive.

JESSICA WILSON: Right, it does sound positive and whatever I'm given I can handle it, no one is able to tell me that I am not good enough or I didn't work hard enough. But of course that results in black women especially, working twice as much to earn half as much. But overworking yourselves and just basically killing ourselves to be treated the same way that our peers are treated in the work place. So my goal is for black women to just be regular and just be in a work place or in another environment, so that we're not overworking ourselves. We know that stress more than our weight is a contributer to our health, and so however all of these things lining up for us.

KAYTE YOUNG: That section when you were describing wanting to be ordinary. Especially at work, just that such a simple desire.

JESSICA WILSON: Yes, to just be average.

KAYTE YOUNG: In this book you want to rewrite the narrative about black women's bodies. What is involved in that and how do you see that happening?

JESSICA WILSON: A colleague of mine, Dashawn Harrison talks about the need to have a new idea because all of the things in the last 500 years are really started based on white supremest ideas. And I would love for a new society to be created for sure, but because we are here how can we implement policies, how can we start deconstructing caste in our own environments, what does that look like? But also how can we talk about black women? So those are ideas that we can start changing today. Is it always about our resilience? Black girl magic is another more fun spin on black women's resilience. So what or how can we talk about black women that inherently celebrates our joy, let's us just be and how can we expect that or demand for that to be how black women are written about? How can we actually care for black women during and after giving birth? What do we need to hear and see in that narrative? And I think those are things that we can change now.

KAYTE YOUNG: Can you say what you mean in the title when you say it's always been ours?

JESSICA WILSON: That one was a more broad title to begin with, but then in all of the ways that, you know, my friends have read and talked about this book, how I started writing it, it became far more. Like how much of our stories, of our joy is really from our ancestors, from our families, from really our origins as black folks and how a lot of that has been taken away. So, how can we bring that back? How can we find joy? And because our joy has always been ours and has been used, and will be used as resistance in the US and western society. So how can we center that joy and know that it's always been ours?

KAYTE YOUNG: So the what that's always been ours is joy?

JESSICA WILSON: Yes. The joy is always been ours.

KAYTE YOUNG: I asked Jessica if she would read a passage from the introduction of her book.

JESSICA WILSON: This book is about bodies and how black women are told to have them. The dominant narratives about all bodies were crafted centuries ago and continue to be told today.

JESSICA WILSON: From birth our bodies sets expectations for those around us. This book makes the case for rewriting those narratives. For putting black women at the center of the narratives rather than having our stories filtered through a white lens. I use the body as a vehicle with which we can conceptualize how these stories have shaped our lives and how we might rewrite them going forward.

KAYTE YOUNG: That's Jessica Wilson reading a passage from her book, 'It's always been ours, rewriting the story of black women's bodies'.

KAYTE YOUNG: After a short break we will return to our conversation and hear Jessica's response to the new guidelines from the America Academy of Pediatrics addressing childhood obesity. Stay with us.

KAYTE YOUNG: Kayte Young here. This is Earth Eats. My guest is Jessica Wilson, author of 'It's always been ours, rewriting the story of black women's bodies'. Let's get back to our conversation starting with a short quote from the book.

KAYTE YOUNG: The politics and constraints that shapes society shape our bodies. White supremesis, capitalism, objectifies and commodifies individuals. It creates social hierarchies and then makes money by selling us the promise of thinness, health and ultimately wellness.

JESSICA WILSON: Yes, and I think that is also missed and the constantly creating problems in order to be able to sell solutions. Of course, you know, Gwyneth Paltrow and Goop is a great example of how they invent products and just the idea that to get close to purity, wellness offers this. Gwyneth is somebody who has coffee for breakfast and nothing for lunch, and just how we revere her ability to withhold, to go without and how pure and righteous that seems. So we're able to sell a bunch of things that are supposed to make us pure, be it adaptations in our dusts that we're eating or other things that we're doing to make us feel like we're both good people and righteous and well people.

KAYTE YOUNG: The American Academy of Pediatrics has issued new guidelines recently in the treatment of overweight and obese children, and the guidelines involve intensive health behavior and lifestyle changes. They say that the most effective treatments include 26 or more hours of face to face, family based, multicomponent treatment, over a three to 12 month period. Then for kids that are 12 and over, weight loss drugs like medication might be recommended. For teens that are 13 and over with severe obesity, bariatric surgery is one of the options and I want to know given the work that you do and the perspective from which you approach that work, I would love to hear your thoughts about these new guidelines.

JESSICA WILSON: I appreciate that there have been critiques of body mass index already in popular culture, and in science. And when I was learning about BMI, we initially were told that it was only for population studies, it wasn't to be used for the individual at all. As I was doing training, that evolved into having BMI being used for individuals in a medical setting but like never something that we're supposed to calculate on our own and never ever supposed to be used for children because what we're worried about with children is whether or not they're growing proportional to the growth chart, not like their overall weight.

JESSICA WILSON: So if kids are growing normally, then they may be higher on the growth chart but it's not a cause for drastic alarm, and there were no BMI growth charts like there are now. That has been like a recent development to use BMI for children, something that it was never intended to do, but also it was never really a tool for anything in the first place.

JESSICA WILSON: It's complicated and harmful on so many levels. Basically for kids and lifestyle changes, being told to lose weight or having focus on your body is one of the primary predictors of getting eating disorders later in life. Initially my concerns are that we're just creating eating disorders for children that we weren't doing before hand, there will be more kids and adults with eating disorders. But also something that happened for me personally was that I was in an unsafe neighborhood. I couldn't go play, I was an only child, I didn't have anyone to play with in the backyard. Once I moved to a safer neighborhood where I was able to play from seven AM until sundown, my weight just naturally went down.

JESSICA WILSON: But having been told that I needed to eat less, that continued to stick with me. Like I continued to think that my body was a problem and that I should be celebrating my weight loss as a ten year old, when in fact it was just something that happened and it should have been able to happen without getting praise because then I forever associated weight loss and that praise with something that was good. And through not great times, trying to maintain that praise for my medical providers and family.

JESSICA WILSON: So in short, I think the guideline are incredibly harmful. Putting kids on weight loss drugs that have not even been used in children, and not even used in adults for a long period of time, we have no idea what the new injectable weight loss drugs are going to do to people in the long term. We know that as soon as people stop taking the injectables that they regain the weight. What I am seeing initially are studies showing that even if people stay on the medication, they end up regaining the weight after a while. So putting somebody at 13 on an injectable weight loss drug, are we expecting them to be on the drug for 70 more years? That seems wild and inappropriate and unsafe to me. And as kids are growing, we don't want to have them restricting calories.

JESSICA WILSON: Our metabolisms are still developing at that time. Their risk for malnutrition is higher. I have seen kids who have made do on very few calories, either due to food apartheid, not having food access or dieting very young. Having very, very slow metabolisms later in life and those are things that we can't undo.

KAYTE YOUNG: I want to pause here for a moment on reflect on what she just said. Restricting a child's food intake can lead them to have an extremely slow metabolism later in life. When you have a slow metabolism, it makes it easier to gain weight and more difficult to lose weight. So these early food restriction interventions which are based on faulty data such as the body mass index, are likely to set people up for ongoing losing battles with weight for the rest of their lives. Okay, back to Jessica Wilson.

JESSICA WILSON: In short, I think it is a recipe for disaster. I also know and we know, when it comes to BMI, black and brown kids are often just naturally more muscularly and bone dense. So this of course is going to disproportionately impact black and brown kids, which is partially be design for how we already police the bodies of black and brown kids.

JESSICA WILSON: In essence this is just new guidelines to police chubby kids, black and brown kids, but also real capacity to cause harm. Weight loss drugs in addition to those injectables, are stimulants and we don't want to be putting kids on stimulants when it's not at all indicated. Those ones lead kids to not eat all day. I worked with kids with ADHD and they just don't eat until eight PM, because they're not hungry and they're kids. They're running around and not thinking about food.

JESSICA WILSON: Also phentermine is back because of the increased focus on weight loss medications, and that one is known to have side effects of heart problems, high blood pressure in folks that didn't have it beforehand. I mean I have lots of thoughts as you can tell. Overall I think it's terrible and I'm really hoping that we can push back on the guidelines and undo them.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes, I mean one of the things that came to my mind as you were talking is that, if the BMI is not a good measure of whether a kid is on the road to being an overweight or obese adult, because it can't be if it's not designed for measuring child growth.

KAYTE YOUNG: Anyone who's observed a child growing knows that there are stages where you're chubby and then they thin out, and then they get chubby again and then they thin out, because they're growing in different rates and different ways. If you're using that and then applying treatment based on that, it does seem dangerous to me and harmful.

JESSICA WILSON: And also, if we're giving these 20 however many hours of consultation to people who don't have food, to people who don't have enough money to sustain food all month long, to people who don't have safe places to be physically active, what are we doing and why are we just making kids and families feel bad is what it comes down to. So really why are we addressing the individual when there are so many things that could happen in an environment? And it's business as usual. It's like blame people for things that are completely outside of their control.

KAYTE YOUNG: The guidelines, they acknowledge that this isn't going to be accessible to everybody. That these programs don't exist, and where they do exist, they don't have the capacity to even be there for the families that supposedly need them, not to mention the families aren't going to be able to show up for 26 hours or whatever. Yes, it seems unlikely.

JESSICA WILSON: Yes.

KAYTE YOUNG: Did you want to say more about what are the systemic or structural problems that you feel like they're missing when they focus on the individual?

JESSICA WILSON: In the medical field today, we're very aware of what contributes to somebody's weight. A lot of it is genetics, a lot of it is environment; environmental pollutants and toxins and hormone disrupter's, trauma. We're very aware that adverse childhood events directly impact our weight and our health generally. Access to food, so many different things that impact our natural body weight, whether or not there's a history of starvation either while our parent was pregnant with us. But the answer is never to fix those things, it's diet and exercise.

JESSICA WILSON: These are all so many reasons that contribute to your body size and you know what you need to do, you need to eat kale and quinoa and start jogging. That's an individual solution, which is wild to me.

KAYTE YOUNG: One of the things that I know has been discussed about this, is that they're talking about how health care providers need to take a really aggressive approach and they need to bring up weight at every visit. What do you think about how that might affect someone's relationship to the health care system going forward?

JESSICA WILSON: I mean that's totally what happened to me as a kid and I again, viewed my body as inherently a problem to be solved for decades maybe, at least a decade and a half. And yes, so many of my black friends especially just won't go to the doctor. We won't go places where we've been told we need to lose weight. My fat friends as well just won't go to the doctor until we're very sure something is actually wrong, because if it's not, the solution to whatever it is will just be to lose weight. Whatever is bothering you will be better once your BMI is under 25. So yes, all of these things directly impact our access to health care, or at least access to health care that believes us about our bodies. I see it all the time. I see people be misdiagnosed, not believed, not diagnosed until something is life threatening. All of these are outcomes that may have been considered and just shoved away because people don't care about people's BMI's over 25, I don't know.

KAYTE YOUNG: One of the other things that I noticed in the language was that they're talking about obesity as a disease, not as a condition that causes, or could lead to disease. But they're calling it a disease itself, and that to me feels new or is that something that's been going on for a while?

JESSICA WILSON: I think honestly the conversation has evolved over time. I feel like in the Biggest Loser, Let's Move campaigns, my 600 Pound or 500 Life, the language was a lot about this will lead to disease. All of these things are bad because you're going to be a bad parent or a bad employee. So if you lose weight then things are going to be fine. But yes, it wasn't looked at like as a disease in and of itself, but yes, absolutely that is changing and has changed. So people themselves regardless of whether or not they have any of the things associated, causation but not correlation, with their weight even if they don't have any of those things, people are still looked as if they're a ticking time bomb if they're overweight.

JESSICA WILSON: You may not having anything wrong with you now, but just give it six months or whatever. People again and again are fine but the problem is their weight, it's not retreating or diagnosing anything else.

KAYTE YOUNG: You know I understand how maybe when we started talking about addiction as a disease, it was a way to destigmatize. It was a way to say look, this isn't personal failing, this isn't a willpower issue. This is something that was a condition you have and you have to treat it like a medical thing. But it just feels like with this it's different because they're saying the shape of your body, the size and shape of your body is the disease and that feels like exactly what you started talking about; about the pathologizing of a body and if you're doing that to a child.

JESSICA WILSON: What's not mentioned is how instrumental pharmaceutical companies have been in that development. We're having obese people centered language and in these processes, but it's 1000% pharmaceutical companies who are then saying, if you're experiencing weight stigma because you're overweight, let us help you, it's a biological thing, here's a drug, Vyvanse, or any of the injectables, that will cure your experience with weight stigma, let's sell you this product.1000% it has been the pharmaceutical companies creating a disease so then they can sell the cure.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes, and I don't really feel like we have time to go into it, but I just know that the bariatric surgery also has all sorts of complications. When you're talking about teenagers, a 13 year old, that seems pretty intense intervention.

JESSICA WILSON: We only talk about it from a weight loss perspective. But when we're moving organs, especially children's; there are minerals, vitamins and nutrients that are absorbed all along the way. And that won't happen, and that is really needed in growth and development. So it's especially concerning for children, but I know many adults who are not able to eat an entire egg. They are on protein shakes for the rest of their lives, and that's the only thing that they're able to eat, otherwise they will vomit. So these are just things that happen in adults. Why are we going to risk that in children? And yes, there's no research on the impacts of growth, of development of kids.

KAYTE YOUNG: A lot of the discussion that I've heard around this, and it's in the guidelines as well is that, one of the reasons why this intervention is needed is because of the stigma and how harmful that stigma is for children. And that kids are getting bullied in school and other places, because they're overweight, and that's one of the reasons we have to address this and I would just like to hear your response to that.

JESSICA WILSON: Yes, that's wild. That's like condoning bullying for kids who are whatever size they are, and then blaming the kid first of all, and not at all addressing the bullying. And then telling kids that it's their fault for getting bullied and they need to change it. We don't do that for other things. I mean some religions will try to make gay people straight, but still in school bullying is not okay. But why all of a sudden, yes, are we calling it weight stigma based bullying, and if you're just then if we make you thin, you won't experience it and so that's a reason for us to tell you to diet and exercise.

JESSICA WILSON: Like complete disregard for kids is how I think about it. Reinforcing fat phobia and why it's okay to be mean to fat people. It's not just like the interpersonal stuff, but how does that creep into whether or not people get jobs, how people are viewed as potential partners. When we look at it in the medical research, people are thought to be lazy and non-compliant. People don't get care, people aren't believed. So it's not just kids and bullying, that sets people up early to think that it's okay to discriminate against chubby kids and larger adults.

KAYTE YOUNG: It just feels like there are some, I don't know if blind spots is the right word to use, but just that it's like the main thing that's wrong is that you're overweight and so let's just make you not overweight anymore, and then these problems will go away.

JESSICA WILSON: Yes, absolutely.

KAYTE YOUNG: It just feels like a very harmful message to send.

KAYTE YOUNG: I really want to thank you for talking with me today.

JESSICA WILSON: This was great. Thanks so much for having me.

KAYTE YOUNG: That was Jessica Wilson. She's a dietitian, consultant and story teller, and the author of the book, 'It's always been ours, rewriting the story of black women's bodies', released in February of 2023.

KAYTE YOUNG: You can find links to her work and to the new childhood obesity guidelines from AAP on our website, Earth Eats dot org.

KAYTE YOUNG: That's it for our show this week. Thanks for listening and we'll see you next time.

The Earth Eats’ team includes Violet Baron, Eoban Binder, Alexis Carvajal (CAR-veh-hall) Alex Chambers, Mark Chilla, Toby Foster, Daniella Richardson, Samantha Shemenaur, Payton Whaley and Harvest Public Media.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week to Jessica Wilson.

Earth Eats is produced and edited by me, Kayte Young. Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from Universal Production Music. Our executive producer is Eric Bolstridge.