Barren, dry pasture ground lies on one side of this road in Scotts Bluff County, Nebraska, in 2022. Springtime drought sets up a challenging year ahead for farmers and ranchers. (Tiffany Johanson / Nebraska Public Media)

Spring is the time for planting crops and turning cows out to graze — yet in parts of the central U.S., dry conditions are upending the growing season.

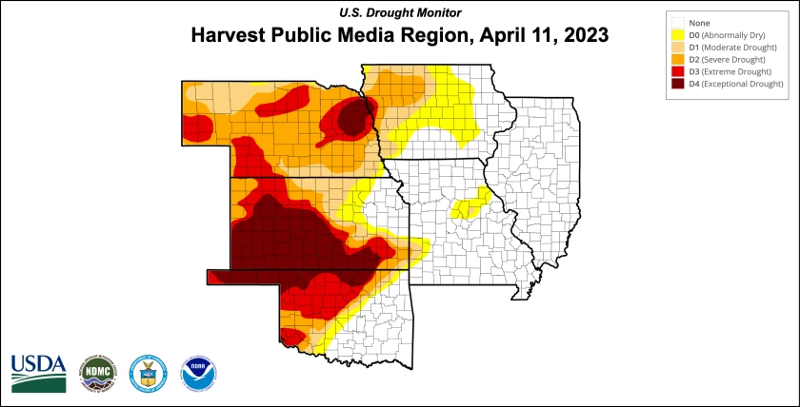

Missouri, Wisconsin and Illinois received enough precipitation over the winter to help relieve much of last year’s drought conditions, setting them up well for the spring season. However, parts of Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma continue to experience severe drought, and farmers and ranchers are trying to adjust.

Dennis Todey, the director of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Midwest Climate Hub, said it has been surprising, since winter usually brings some precipitation and spring even more.

“Yet we still have these large pockets that have not improved much and actually have seen some areas recently worsening,” he said.

Even if drought-stricken areas did see some precipitation, Todey said it takes more than a couple of rain storms for drought to diminish completely.

“Getting back out of this severe drought takes some time,” he said. “You need several larger [rain] events that help replenish the soil moisture.”

A slower planting season

The amount and timing of rain will be especially important in drought-stricken areas this spring. Mark Licht, an associate professor and extension cropping systems specialist with Iowa State University, said it will make or break the growing season.

Farmers with arid fields are currently making the decision to either plant their usual crop this season, such as corn, or switch to drought-tolerant crops like sorghum to help them get by this year. Others are timing when to plant crops with possible rain showers.

“That's the real challenge with drought,” Licht said. “How do we make strategic changes to make sure we can still get some crop production out here? And basically, what we’re left with is, ‘Can we move into more drought-tolerant type of crops?’”

Licht said switching to agriculture practices like no-till and using cover crops can help build soil resiliency through drought spells, but farmers won’t be able to reap the benefits until years later.

“In the short-term, there's really not much you can do,” Licht said. “A saving grace that we have in some of the Great Plains states is irrigation to use as a tactic to reduce drought impacts. But it can only be part of the solution.”

Tough decisions for ranchers

After nearly three years of drought conditions, the U.S. cattle inventory is in short supply, said Derrell Peel, an extension livestock marketing specialist for Oklahoma State University.

With dried-up ponds and little feed supply, the drought has forced cattle ranchers to slaughter livestock early for the past two years. Last year had the most beef cows slaughtered since recordkeeping began in 1986, according to a USDA livestock report.

“The drought impacts really kicked in about 2021 and 2022,” Peel said. “So the total herd coming into 2023 was down about 2.8 million head of cattle from the peak in 2019. So in about three years, we have liquidated about 8.7% of the [U.S. cattle] herd.”

Peel explained there will be a sharp drop in beef production this year as cattle ranchers try to maintain their smaller cattle herds and rebuild their herd size, which could lead to higher prices for shoppers at the grocery store.

“There is this unknown from the consumer standpoint of just how much higher can they go before we really start to see consumer reaction in terms of shifting away from beef to other meats,” Peel said. “We don't necessarily see that happening too much yet, but at some point, it will happen as consumers try to minimize the impact of higher prices on their personal budgets.”

As drought continues to rage on this year, ranchers still haven’t had the chance to recover and are faced with limited grass and water availability for their cattle herds.

For instance, winter wheat, a grain crop used for feed that’s primarily grown in Kansas and Oklahoma, recently tied for the lowest quality rating in 40 years, according to the USDA’s April 10 crop progress report.

“When you start the year in drought like we are right now, you don't grow anything, Peel said. “And so not only do you not have anything now, there's no prospects of getting anything anytime soon.”

But Peel notes it's not the first time ranchers are enduring the impacts of a multiyear drought.

“The industry will survive, and they will recover,” Peel said. “It's a tough thing, but it's also not really an uncommon thing in this part of the world.”

An emerging weather pattern could bring drought relief

Todey, director of the USDA Midwest Climate Hub, said it's difficult to pinpoint a single reason for the region’s continuing drought, but the various storms that pummeled the Southwest and California region this year and helped alleviate their drought play a factor.

He explained those storm systems moved across the Northern Rockies, Plains and upper Midwest regions and brought decent-sized rain and snow showers. But those storms shied away from the Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma regions.

Hopefully, he said, that will change.

Last month, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced that La Niña, the weather phenomenon that’s helped fuel droughts across the West and Great Plains for nearly three years, is gone. While the world currently stands in a neutral climate pattern, the NOAA predicts the weather phase, El Niño, which tends to bring more rain to the Midwest, will likely arrive this summer.

But Todey said despite expected rainfall, the effects of the drought will be felt for a while. Bone-dry and windy conditions have already helped fuel wildfires across parts of Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma this year. Dust storms are also another consequence of drought as strong winds can kick up dry soil in the air.

“We still are hoping that this spring, we'll get some decent amounts of precipitation that will help move things forward,” he said. “But the severity of the drought and the depths that we're dealing with, it's hard to imagine that we'll be able to recover all of this over this whole area.”

This story was produced in partnership with Harvest Public Media, a collaboration of public media newsrooms in the Midwest. It reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.