The 2023 Farm Bill is estimated to cost more than $709 billion over the next five years, the most ever. And with a debt ceiling fight looming between Republicans and Democrats in Congress, it could be a tough year to get the omnibus bill passed. (Illustration By Xcaret Nuñez. (Photo Credits Below.) / Harvest Public Media)

Lawmakers are in the process of shaping one of the biggest legislative packages moving through Congress this year: the 2023 Farm Bill.

Few Americans are farmers, yet the bill still has a big impact on the rest of us.

“Anybody who eats or wears clothes that are generated from natural fibers, is actually touched by the farm bill,” said Amy Hagerman, an assistant professor at Oklahoma State University and a state extension specialist for agriculture and food policy.

Congress renews the farm bill about every five years to set the stage for our food and farming systems — including what crops farmers plant.

The bill controls how billions of taxpayer dollars are used to set up crop insurance, fund crop subsidies and agricultural research to assist food production, as well as invest in sustainable agricultural practices. It also maintains food assistance programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which supports nearly 42 million Americans.

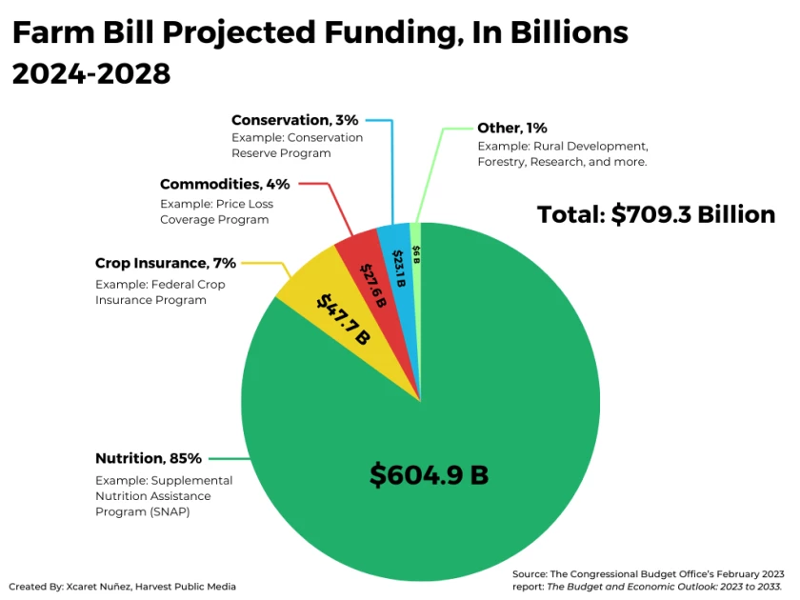

The farm bill consists of about a dozen sections called titles, and the Congressional Budget Office estimates the 2023 Farm Bill will cost about $709 billion over the next five years — the most expensive on record. Much of that money is spent on four major titles: nutrition, crop insurance, commodities and conservation.

With the $31 trillion debt ceiling crisis looming over lawmakers, agriculture policy experts say the cost of programs will drive farm bill 2023 policy discussions.

“There will be intense conversations around those different priorities,” Hagerman said.

A divided Congress, with Republicans having a slim majority in the House and Democrats in the Senate, sets the stage for tough negotiations as the Sep. 30 deadline approaches, and the 2018 Farm Bill expires.

What is the Nutrition Title?

The Nutrition Title is the biggest piece of the farm bill pie. It’s estimated to account for 85% of farm bill spending — up nearly 10% from the 2018 Farm Bill — to support low-income food assistance programs like SNAP.

“When you get 40-some million people in a program, it's going to spend a lot of money, and so that's just the reality of it,” said Jonathan Coppess, associate professor and director of the Gardner Agriculture Policy Program at the University of Illinois.

As lawmakers look at ways to scale back federal spending, Coppess said some are looking to trim from SNAP.

“If budget is driving our whole discussion, then we're looking around for big numbers to cut,” he said. “And this is a big number, so it gets the first focus on cutting.”

Coppess said the fight to slash SNAP isn’t new when it comes to farm bill negotiations. House Republicans introduced a bill earlier this year that would establish stricter eligibility requirements, including making more SNAP participants subject to work requirements. SNAP already has work requirements and limits food assistance to three months of every three years for able-bodied adults ages 18 to 49 without dependents.

“The work requirements discussion that we hear about is rooted in this kind of mindset … that somehow these [SNAP] policies are motivating people not to work,” he said.

While Republican lawmakers, such as Rep. Dusty Johnson (R-S.D) argue "work is the best pathway out of poverty,” Democratic lawmakers are opposed to making cuts to SNAP benefits, saying it would hurt families that most need assistance.

Meanwhile, the current U.S. unemployment rate is at 3.4%, the lowest it’s been since 1969.

What is the Crop Insurance Title?

The Crop Insurance Title is the second-most expensive piece of the farm bill and is estimated to account for 7% of the bill’s spending.

The title controls and funds an insurance program farmers and ranchers can purchase to protect against losing their crops to natural disasters like drought or damaging storms — but only a handful of crops are eligible for coverage.

More than 80% of all planted corn, soybean, wheat and cotton crops in the U.S. are covered by crop insurance policies on average, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, while very few fruit, vegetable and organic farms receive coverage.

Patrick Westhoff, the director of the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute at the University of Missouri, said the discussion to reform the crop insurance program and make it more accessible to smaller farmers has risen in previous farm bill cycles.

But Westhoff said it can be an expensive process, even for a special commodity.

“They're trying to find ways to make that a more affordable process to make it easier to get those programs established, even for some products that don't have as high of a value of production as some of the major crops,” he said.

While some farmers are content with the existing crop insurance program, Westhoff said others are pushing lawmakers to strengthen the program for farmers experiencing more and more crop losses due to climate change. In recent yearsfarmers have received billions of dollars in crop insurance payouts due to extreme weather.

“We may well have a record level of indemnity payments for losses incurred because of crop problems in 2022,” Westhoff said. “But it's also because crop insurance is going to pay based on the value of the crops insured. So if prices are higher now than they were 10 or 20 years ago, that means the value of the crop’s insurance is higher.”

The Congressional Budget Office estimates crop insurance will cost over $48 billion over the next five years, which makes it another place lawmakers might look to cut spending on or use as a leveraging tool to get the changes they want in the title, Westhoff said.

What is the Commodities Title?

The Commodities Title is the third major title in the farm bill and is estimated to cost $27.6 billion over the next five years for 4% of total farm bill spending.

It provides subsidy payments, money paid by the federal government, to farmers that grow certain commodities like corn, soybeans, wheat and cotton when the price of a commodity crop drops below a certain threshold.

It was a part of the original 1933 Farm Bill, a time when a quarter of the U.S. population was farmers, and the program was intended to secure the food supply by keeping farmers in business.

But it’s a policy some lawmakers and farmer advocacy groups argue only benefits large farms, Westhoff said. The Environmental Working Group, a progressive advocacy organization, recently called attention to nearly 20,000 farmers having received subsidies for 37 consecutive years.

“For the most part, the programs are set up to provide payments that are proportional to the value of production on a farm. So the larger the farm, the larger the payments,” Westhoff said.

Meanwhile, some farmers are pushing lawmakers to raise market prices as they haven’t kept up with inflation, and as a result, they have received little to no commodity payments, he said.

“We have relatively high prices for most agricultural products today,” Westhoff said. “Well above [market] prices. So under current policies, the commodity title will spend very little money in the current year.”

Crop insurance and commodity programs both indirectly impact consumer food costs as they go toward supporting the crops farmers grow and livestock ranchers raise, but Westhoff said, it’s not something that would impact grocery store prices overnight.

What is the Conservation Title?

The Conservation Title is estimated to take up 3% of the 2023 farm bill spending, with a projected cost of $23.1 billion over the next five years.

It covers voluntary federal programs that encourage farmers to take on agricultural practices intended to conserve natural resources. Conservation programs aim to reduce soil erosion, protect drinking water, preserve wildlife habitat, and preserve and restore forests and wetlands.

Coppess, of the University of Illinois, said climate change will be at the center of lawmakers’ conversations surrounding the conservation title. The Inflation Reduction Act Congress passed last year invested $20 billion in conservation programs, specifically to invest in climate-smart practices over the next five years.

“This really historical investment from the Inflation Reduction Act around climate change is something we've not ever seen, to that degree, outside of the farm bill debate,” Coppess said.

Although the U.S. Department of Agriculture has already begun rolling out IRA funding, Hagerman, of Oklahoma State University, said it’s too early to tell how it will impact farm bill discussions.

“There's just so many different ways within and outside of the Conservation Title, that [investment in climate-smart practices] could come into or be done outside the farm bill,” Hagerman said. “I think this is a broader trend in moving in that direction, but with no one obvious path forward for accomplishing it.

What has happen for the Farm Bill to pass?

Lawmakers in both the House and Senate need to agree on a new version of the farm bill and have the president sign off on it by Sept. 30, the expiration date of the 2018 Farm Bill.

If Congress doesn’t pass a new version in time, programs under each title are affected differently. Some programs have a permanent authorization, which means lawmakers can vote to extend them, which they've budgeted for. Other programs revert to rules from the original 1933 Farm Bill, while others just expire.

Historically, the farm bill has largely been a bipartisan effort, but with lawmakers focused on figuring out a debt ceiling plan, it could be difficult to get a bill passed in time this year.

“If they want to make any kind of big changes to that farm bill, you know, the pie is only a certain size,” Hagerman said. “So they're gonna have to make one piece smaller if they're going to make another piece larger, anywhere else.”

This story was produced in partnership with Harvest Public Media, a collaboration of public media newsrooms in the Midwest. It reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.