KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana, this is Earth Eats and I'm your host, Kayte Young.

MAX HAIVEN: When you begin to zoom out, you realize that in fact, palm oil is all around us and the world, in a strange way, is made of palm oil. And indeed we are all in a certain way made of palm oil, in the sense that we use it to reproduce our bodies and to clean our skin and to live the lives that we live in a globalized world.

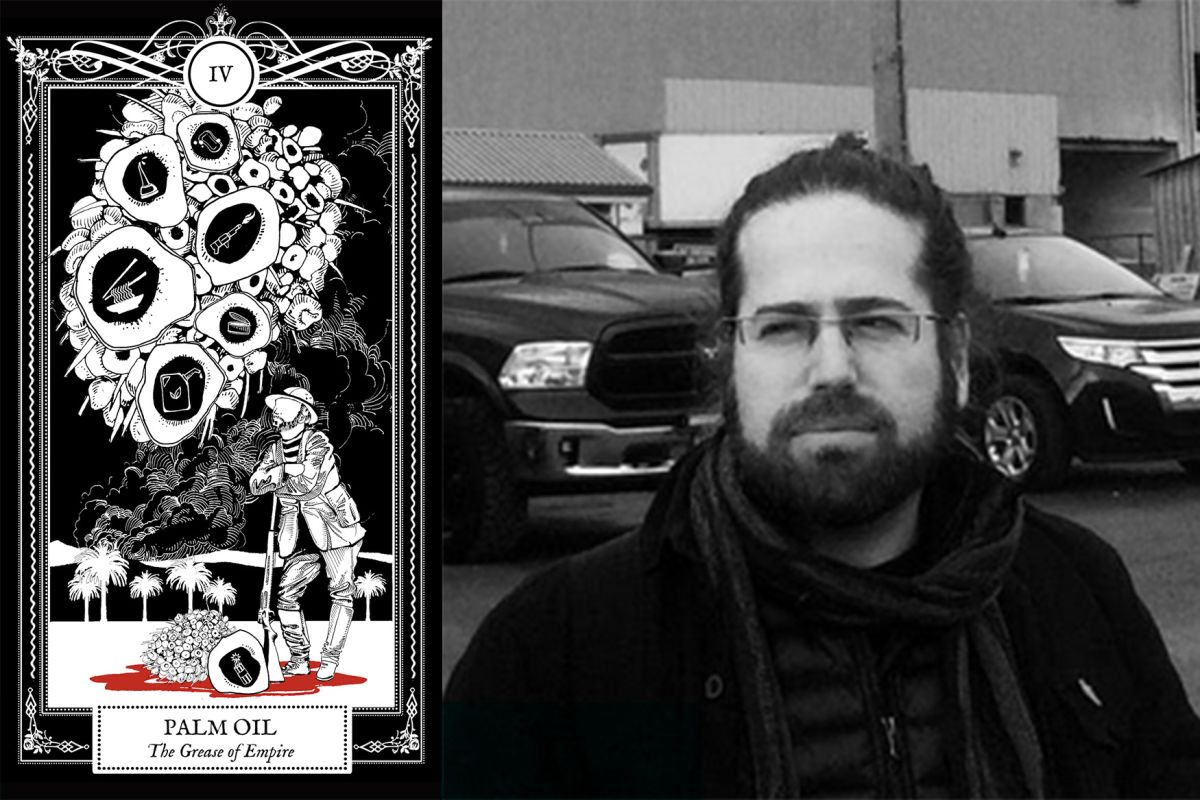

KAYTE YOUNG: This week on the show, a conversation with Max Haiven, author of the book Palm Oil, in which he traces the history of palm oil production globally, examining its damaging effect on the environment, the labor abuses in the industry, and the harmful effects of this cheap fat, on the health of the people who consume it. An exploration of what palm oil can tell us about our global economy, climate change and who we are. That conversation is just ahead. Stay with us.

KAYTE YOUNG: Thanks for listening. I'm Kayte Young. One of the topics we like to explore on Earth Eats is the examination of our food systems and we do that from a number of different angles. We look at farming practices, food production and processing, food preparation or cooking, access to food or lack thereof, and I'm interested in food for its own sake. It's endlessly fascinating, but I'm also intrigued by what the study of food can show us about other facets of our culture and who we are.

KAYTE YOUNG: This week I'm talking with Max Haiven.

MAX HAIVEN: My name is Max Haiven and I'm a writer and a teacher, and I work as the Canada Research Chair of the Radical Imagination at Lakehead University which is on the north shore of Lake Superior in Canada.

KAYTE YOUNG: He has a new book out about palm oil. Palm oil is extracted from palm kernels, which, obviously, grow on palm trees. It's one of those fats that remains semi-solid at room temperature, and it's used in many products. From cosmetics to computer parts and it's listed as in ingredient in almost all highly processed foods. Grab a random snack food off the grocery store shelf, check the ingredient list, I bet you'll find palm oil on there. Max Haiven is not a food scholar, but through his study of palm oil, I knew he would have some interesting things to share with us about our food systems, about health, about labor and capitalism, and about the environmental costs of so-called cheap food production.

KAYTE YOUNG: I started by asking him to tell the story of how he found his way to this topic.

MAX HAIVEN: It has a strange history, because I was teaching in an art school and not only am I not a food scholar, I'm not an art historian. But somehow I ended up teaching in an art history department because I told them, truthfully perhaps, that I could teach the students something about capitalism. The kind of economic system that we all live in. And they hired me at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design to teach students about material culture, which is the study of where things come from, how they work. You know, you can imagine for artists making crafts, they have an interest in where their stuff comes from.

MAX HAIVEN: And I was looking for one commodity that in the design of my course, could take us through the entire semester. Where in each unit we could look at a different aspect of history or our contemporary world, and unpack this one thing that was in everything. And through a kind of roundabout route I came to palm oil. It started when I was studying how objects transform when they're brought into a museum. So, I looked at the theft of what have come to have been called the Benin Bronzes, which were stolen from the Edo Kingdom in West Africa at the end of the 19th century, and they ended up in the British Museum.

MAX HAIVEN: And in the Edo Kingdom, they had a variety of uses, ceremonial and historical. When they came to the British Museum, they became kind of signifiers of the superiority of the British Empire as kind of war loot. But underneath that story - and I was able to tell that story to my students about how a sculpture can have different meanings, depending on where it's located. Underneath that story is the story of palm oil, because in fact the British invaded and destroyed the Edo Kingdom. Not because they wanted these artworks, as beautiful as they are, but because they actually wanted to secure the palm oil production capacity of that kingdom. And it was part of a series of sort of wars in the later part of the 19th century, of the British Empire and other empires, to secure resources like palm oil.

KAYTE YOUNG: And that story really shows up in the book. You really talk about also how that war was sold to the British people, in terms of trying to confront human sacrifice.

MAX HAIVEN: You know, the 19th century in England was a scene of massive class war. You had the ruling class, really, putting the working class of England and the rest of the world, under incredible pressure and constraint, really murderous conditions in factories. And as the 19th century progressed and workers' uprisings got more and more militant, the ruling class was essentially looking for ways to buy off or co-opt the working class in England. And one of the main ways they did that was through narratives of empire and racism. So, you began to see the development of commodities, including soap and candles. Both of which were made out of palm oil in the 19th century and some of them are still made out of palm oil today, being sold to people as a kind of act that by buying these commodities, they could help the British Empire, rather than being in opposition to their bosses.

MAX HAIVEN: Everyone could be on the same side, spreading what they, in the white supremacist imagination, imagine to be civilization to the world. And one of the key ways that this was presented was that, you know, many African civilizations, including the Edo Kingdom, were practicing this so-called, barbaric act of human sacrifice and that needed to be stamped out and eradicated. And it was said at the time that buying palm oil candles, buying soap made out palm oil, would help introduce the spirit of what John Stuart Mill called Gentle Commerce to the African people. And sort of slowly and subtly dissuade them from their so-called barbaric practices.

MAX HAIVEN: But of course what this erased was the fact that, as horrific and barbaric as indeed human sacrifice is, Europeans were also committing human sacrifice. They just did it through the sort of allegedly neutral economy or through empire itself. So, you know, famously the Edo Kingdom itself was put on the sacrificial altar in the name of empire. Millions of English workers lost their lives in factories or to malnutrition. Hundreds of thousands of sailors in the British navy lost their lives. Women had a life expectancy in the late 19th century of 30 years at best in the working classes.

MAX HAIVEN: So, there was a kind of human sacrifice going on in Europe at this time, but somehow you could sort of mystify that or displace it by pointing to the other in Africa and saying, "Oh, they're the ones who are committing these heinous acts of human sacrifice."

KAYTE YOUNG: It's a interesting and compelling argument that you make throughout the book about human sacrifice and how it's carried out in contemporary culture as well. Can you talk a little bit about palm oil and just how ubiquitous it is and how it shows up in so many different aspects of life?

MAX HAIVEN: Well, I always think it's important to begin by saying that, you know, palm oil has been harvested by humans for thousands and thousands of years. For most of those thousands of years, exclusively in West Africa, where people have turned it into a great many things, in a very sustainable way. Soaps, food stuff, a substance that's used in religious ceremonies, many, many uses, for manufacturing things. It was only when Europeans, following the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, began to move inland and trade goods other than human flesh with African empires, that Europeans began to discover palm oil's incredible potential.

MAX HAIVEN: And industrial chemists, mostly in Liverpool, began to develop different ways that it could be refined and used in a whole variety of things. So, as we were just discussing, early on it was used in candles and in soap, but it was also used in railway grease and the lubricants that were used during the Industrial Revolution. Since then, it's also taken on many other roles. It's a very easy to access source of glycerins. So it was used in nitroglycerin it was used in explosives, both for weapons, but also for explosives for building roads and railways.

MAX HAIVEN: It was used in the manufacture of tin cans. And really most of those uses have passed by with the advent of petrochemicals, later in the 19th century and early 20th century. But today, in fact, the use of palm oil is even more ubiquitous. It's really all around us and in a huge number of things. Some reliable estimates that are often quoted suggest that it's in 50% of all the products you would find in a supermarket. And that includes, as one might imagine, sort of processed snack foods. So, you know, famously Nutella, and other foods that have that kind of butter-like consistency. Because palm oil's quite unique in having a very high proportion of saturated fat for a vegetable oil, and that saturated fat keeps things semi-solid at what we consider to be room temperature.

MAX HAIVEN: So, it's in many processed foods. It's a very cheap oil, because of the way it's cultivated and refined, at the expense of people around the world, and at the expense of rain forests around the world. And because of that it's also found in a lot of deep-fried snacks, in a lot of cheap packaged baked goods. It's also elements of palm oil are used as emulsifiers or preservatives or coagulants in a whole variety of foods, and trace amounts in a vast number of processed foods. But it's also found in many, many detergents and soaps, in, I would say, probably most cosmetics.

MAX HAIVEN: It's also often used in the manufacture of dyes. Sometimes it's used in the manufacture of paper. It has been used as an additive in industrial processes for manufacturing electronics and it's also more recently been adapted into an agrofuel. So it's basically converted into something, into ethanol that can be added to gasoline and diesel, to try and improve the ecological profile of those fossil fuels. So, when you begin to zoom out, as I try and do in the introduction to my book, you realize that in fact palm oil is all around us. And the world, in a strange way, is made of palm oil, and indeed we're all in a certain way made of palm oil, in the sense that we use it to reproduce our bodies and to clean our skin and to live the lives that we live in a globalized world.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay, so now that we know what we're made of, let's take a short break, before returning to my conversation with Max Haiven about his book, Palm Oil. Stay with us.

KAYTE YOUNG: This is Earth Eats. I'm Kayte Young. Let's return to my conversation with Max Haiven. He's the author of the book Palm Oil: The Grease of Empire.

KAYTE YOUNG: I was thinking we should probably back up a little bit, because I'm assuming that listeners know what some of the problems are with palm oil and we haven't actually specifically talked about that. So, it is considered a cheap oil but there are a lot of costs that are associated with it, that may be sort of invisible on the surface. Could you talk about some of those costs, both in terms of human beings and labor and in terms of the environment?

MAX HAIVEN: Absolutely. Well, let's begin with humans and then move to non-humans. For humans, palm oil is not by any stretch of the imagination a healthy oil. In its raw red virgin form that's been cultivated for thousands of years in West Africa, it has many nutritional qualities. But the kind of bleached, deodorized palm oil that we tend to get in our processed foods, is quite unhealthy. And that's of course unhealthy for consumers in the so-called sort of global north, who are eating processed foods like Nutella or processed baked goods. But it's especially unhealthy for people in the global south, for whom palm oil has become the cheapest oil that they can afford.

MAX HAIVEN: So, famously the world's second single largest importer of palm oil is India, where it's used as vegetable ghee. It's the staple cooking oil. And it's displaced the production of oil of local farmers, so that now not everyone, but especially the poorest people in the country, are reliant on this oil. And it's been a major contributing factor to a massive escalation in heart disease in India, because it's partly that the oil itself has a high degree of saturated fats which contribute negatively to heart health. It's also just that it's very cheap and people adapt diets to the resources available, and when fat is one of the cheapest forms of calories, people take in a lot of it. So, there's been a large rise in deep-fried foods and processed foods.

MAX HAIVEN: So, these are may be to speak to some of the effects on the human body of the oil. At the same time though, that pales in comparison to the effects on workers. So, beginning in the early 20th century, England and Dutch empires started moving production of palm oil plantations from Africa to South-East Asia. Specifically the countries that are now known as Indonesia and Malaysia. And following independence in both of those countries, the two rows of the kind of palm oil super powers. Palm oil's also grown still in West Africa for export and in Latin America in many places. And in all of these places, it tends to attract landowners and task masters and entrepreneurs and plantation owners, who are interested in exploiting labor as aggressively as they possibly can.

MAX HAIVEN: So, the history of palm oil production in South-East Asia, for instance, in Indonesia and Malaysia, is the history of this kind of exploitation of one migrant work force after another. Whether they're internally migrants within those countries who have been displaced by Civil War, or whether the migrants brought from other countries who are denied civil and workers rights. This leads to incredible levels of abuse up to this day, that include debt bondage, the exposure of workers to chemicals in the fields, forms of sexual assault and abuse of workers, incredibly destructively low wages.

MAX HAIVEN: It also includes the land-grabbing of territories from indigenous groups and from peasants, and often includes plantation corporations, or sort of local political middlemen who are often being bribed or paid off. Fermenting or encouraging ethnic strife and strife between different groups of workers, in order to make sure that they're fighting against one another and not organizing. There's been a rash of murders of trade union activists and journalists studying the palm plantation industry, both in Indonesia and Malaysia, but also increasingly in Brazil and Colombia, in Guatemala and elsewhere. So, practically any kind of human rights abuse that you can imagine is occurring within the palm oil space.

KAYTE YOUNG: It is a very labor-intensive crop. And so, for it to be cheap, must mean that labor is not being paid or treated the way that they should be.

MAX HAIVEN: Yes. This is exactly the case. I mean, as Raj Patel and Jason Moore point out in their really fabulous book, A History of Capitalism in Seven Cheap Things, there's no such thing as a cheap food. There's foods that are cheapened because the costs are passed on to others. It's cheap labor or cheap land, the cheapening of the environment so that it can be abused and destroyed. Yes, precisely, its cheapness is borne on the backs of these workers.

KAYTE YOUNG: It's not the kind of crop that you can easily mechanize to harvest. Is that correct?

MAX HAIVEN: That's correct. It still requires a lot of human dexterity to cultivate the bunches of palm kernels, which can weigh up to ten or 20 kilos sometimes, that are high up in the canopy. So, you really need humans to do that. The refining has been mechanized quite extensively, but the actual cultivation hasn't. And, you know, even beyond it, there's this old riddle that economists like to point out. That, you know, even if you can mechanize something, it doesn't necessarily mean that it's cheap to do so. If you can find a human being to do the work of a machine cheaper than it is to buy and maintain a machine, then you'll do so, and that's also the case in the palm oil industry.

MAX HAIVEN: So it's not a far jump to realize that if the cheap cost of palm oil is borne on the backs of workers, it's also borne on the back of the non-human world as well. And that's gained a lot of attention over the last 20 years, especially with the sort of charismatic species like the orangutan in Borneo, whose habitat is being lost to deforestation thanks to the palm oil industry. Often the palm oil industry, there are major plantations that are owned by large corporations. But a lot of the land under palm oil cultivation is owned and worked and seized by sort of middlemen, or people who are at arms length from these large corporations, who are supplying the large corporate refineries. And it's become a habit and a practice in both Latin America, West Africa and South-East Asia for these sort of entrepreneurial types to burn down large sections of the forest to make way for palm oil plantations. Including, in South-East Asia, very sensitive peat lands that sequester a huge amount of carbon.

MAX HAIVEN: So, the carbon emissions, even though the palm oil sort of industry claims that palm oil is this renewable source of fuel and oil. In fact, the net result of all of the deforestation that is encouraged by the world's incredible hunger for palm oil, has led to millions of tons of carbon being released into the atmosphere with catastrophic impacts, huge loss of biodiversity, species endangerment. Also palm oil cultivation is often done with intensive pesticides, herbicides and fungicides which then find their way into the water table and have dramatic impacts. And that's to say nothing again of the fact that palm oil is this global commodity, and it is being grown in the tropics and then has to be shipped to its markets, which has many other environmental costs as well.

KAYTE YOUNG: I saw some of that environmental degradation for myself once, on a visit to Costa Rica. Driving down a two-lane road on the way to a lush National Park Rain Forest, we found ourselves in the midst of row upon row, mile after mile, of nothing but palm trees. Planted in a grid, with all the surrounding vegetation stripped away on either side of the road. We didn't realize what it was at first. We had to look it up. I didn't know what a palm plantation looked like. Now, I do. It ain't pretty. In fact, it's rather tragic, because at the National Park down the road, you could experience the rich biodiversity of that place, and recognize quite starkly what is lost when you turn it into a factory for cheap fat. I ask Max Haiven about the palm oil refining process.

MAX HAIVEN: To give the industry its due, they've done quite a lot of advances in refining. So, now they use waste of the other parts of the palm oil production process to fuel the plants, refining plants. So, it is a little more efficient and they've introduced things like carbon scrubbers to make sure that the emissions from the refining plants are not as bad. But often the industry points to this as sort of a showpiece of its move towards sustainability. But when you factor it all in, the refining actually is a very small part of the environmentally devastating aspect of the process.

KAYTE YOUNG: You talk about, with the palm oil industry, that there is some level of green washing or of sort of offering, like you said, as a biofuel. And then also pointing out some production is so-called sustainable, or better than others, or maybe isn't quite as exploitative of people. But then there's also this stigma associated with palm oil in some circles.

MAX HAIVEN: Very much. Starting even as early as the 1950s and 60s, Americans, specifically oil producers, notably the dairy industry and the soy, the growing soy kind of empire in the U.S. They started to sort of target palm oil and other tropical oils as this kind of shifty, kleptocratic oil that came from dubious places with dubious health impacts. And in response to that, corporations and governments in South-East Asia, in Indonesia and Malaysia, sort of responded by hiring a lot of public relations companies to try and clean up the image of palm oil.

MAX HAIVEN: Starting even in the 1980s, but especially in the 1990s and early 2000s, this stigma around palm oil became very attached to its environmental destruction and human rights abuses, such as the ones we've been speaking about. And that led the same sort of PR outfits to suggest creating what would become the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. Which is a transnational opt-in organization that includes representatives of governments from palm oil exporting countries, representatives from corporations, like, end-user corporations like Unilever or Ferrero or these other companies that use palm oil.

MAX HAIVEN: It includes many of the largest plantation companies and refining and export companies. And it also includes many large environmental and human rights NGOs. And the idea was that you would be able to start creating a set of voluntary protocols, that producing companies could abide by, to help ensure that workers rights and environmental rights were supported. The evidence increasingly seems to suggest that that organization is largely ineffective, doing much more than offering the patina or symbolism of sustainability to Western consumers. They do have an internal investigations and complaints process, but some of those investigations take ten or more years, by which time, it's impossible. Even at its best, I believe the statistics are that no more than 20% of palm oil production in the world, is actually within the voluntary guidelines. Because there's this production chain of many subcontractors and subcontractors and subcontractors, going way out into the depths of tropical forests where there are very few police and very few ways to investigate.

MAX HAIVEN: One of the companies that was celebrated by the RSPO as one of its showpieces, Sime Darby, which is headquartered in Singapore, recently was sanctioned by the U.S. Customs Office for Human Rights and Environmental Abuses, leading to a number of companies cutting business ties with them. Sime Darby had been held up as an exemplar of implementing the Roundtable's recommendations on sustainability. And the U.S. Customs Office is not known for being a particularly anti-capitalist organization, eager to enforce human rights around the world. Some of that has to do with, again, going back to those sort of wars between different sectors of the global economy. The soy bean industry is still very much the enemy of the palm oil industry, and they're very powerful. It's certainly within their power to lean on and influence the U.S. Customs Office, for instance, and other organizations.

MAX HAIVEN: Large environmental NGOs also have different kinds of motivations and stakes for remaining part of the sustainability Roundtable. They also, not to be completely cynical, because some of these organizations do very important work. But palm oil has been a very important part of large environmental NGOs' practices. For instance, World Wildlife Fund or Greenpeace, because it's so charismatic. You can go to consumers and say, "Help us save the orangutan," "Help us save the rain forest," "Don't buy these products which you know everyday." That's a very easy thing for a environmental NGO to kind of sell, to use the cynical term, or promote to audiences. Because everyone can recognize something that they like that's threatened, and something that they associate with, which is these sort of commodities that they buy every day.

MAX HAIVEN: It's much more abstract to say something like, you know, "We need to stop the acidification of the ocean by fighting for the regulation C36F at the European Commission." Or something like that. So, palm oil also, there's some incentive there for environmental NGOs to also really focus on it. And part of that's important, but part of that also means that a lot of the nuance of the story gets lost.

KAYTE YOUNG: I hadn't actually realized the part about what you said about the soy bean and corn oil industries talking about palm oil as this kind of shifty, you know, foreign thing, as opposed to this wholesome Mid-Western, completely harmless agriculture that, you know, I'm surrounded with here in Indiana.

MAX HAIVEN: Yes, of course, of course. But this in some ways goes back to that same pattern that we saw with the British capitalism at the end of the 19th century, said, "Don't look at the way that we're treating our workers in the factory, look at these poor Africans over in Africa who need to be saved by our green consumerism." What's lacking in both cases is a kind of holistic sense of this system that we're all entangled with, and that we only have the power to change if we work together trans-nationally.

KAYTE YOUNG: One of the things that I found really refreshing throughout the book is that, you know, you acknowledge the way that we're all complicit in this. We can't avoid participating in the global market of palm oil. Often the response, when we learn about atrocities associated with a product, or we learn about the effects of the product on climate change, is to vow to avoid the item and the kind of vote with your dollar approach. But you don't really take that path, and I was wondering if you could talk about what we miss or what we get wrong when we have that kind of response.

MAX HAIVEN: Well, I guess I always want to start with this question by saying that I think our desire to vote with our dollars, and to participate in boycotts, or to think through consumer activism, comes from a very earnest good place. And it's easy to become cynical and say, "Well, it doesn't work or it's problematic so therefore we shouldn't do it." And that's definitely not what I want readers to take away. I want them to take away a sense that actually much more is possible, if we just challenge ourselves to imagine a little bit more broadly. So, to maybe go into that a moment, I mean, we just spoke a moment ago about the equivalent of, like, green or ethical consumerism in the 19th century. Where these white consumers imagine that they were doing great benefit for people they understood to be more poor, and more needy than them in Africa by buying palm oil candles and soap. But in fact just perpetuated an industry that was destroying African civilizations and leading to incredible forms of exploitation. Including notably by Lever, the entrepreneuring parent of Unilever.

MAX HAIVEN: The brand that today is one of the largest consumers of palm oil and produces many of our most favored cosmetics to this day. Who opened up extremely exploitative plantations for oil palms in what's now Congo and other places in West Africa.

MAX HAIVEN: So, we have to look at the history of this kind of idea of green consumerism, ethical consumerism, to recognize that sometimes when we do something we think is good without necessarily doing research, or acting collectively, or thinking holistically, we can actually be contributing to very problematic systems. I mean, the second thing to simply say about that idea that we should vote with our wallets, is that it in some way cheapens the notion of democracy. Because, of course, those with bigger wallets have more votes and that's not how democracies are supposed to work. And we live in a world of deepening inequalities. We have a tiny handful of very rich billionaires and multi-millionaires who are controlling a huge lion's share of the world's wealth. And those inequalities are incredibly well represented, horrifically, in the palm oil industry where, in the production, you have a handful of extremely rich investors who own large plantation corporations and refining corporations. And then legions, millions and millions of people struggling to get by on the equivalent of mere dollars a day, working in these fields or being forced in other ways to work for the palm oil industry.

MAX HAIVEN: So, if we think about voting with our wallets, we're looking at a system, just in the palm oil industry alone, where the people who run that industry have way more votes than everyone. And if we were just to take a vote with their dollars just now, this system would continue even though it would be millions of people suffering and only a handful benefiting. Beyond that though, I think that there's something that happens to our imaginations when we limit ourselves to thinking about our agency in the world, purely in terms of what can I buy or not buy. What I want readers to get from this book in some way, is that palm oil can show us how deeply entangled we all are on this planet. All of us are using palm oil. We are connected through palm oil to the people who grow it, to the people who cut down the rain forests to make space for it.

MAX HAIVEN: We're connected to those other species, those non-human species, that are being displaced or disrupted by the spread of palm oil plantations. And if we think about that, then we realize that actually we are already collectively making certain choices as a species, as a human species about how we're going to use land and transform the world together. We could make different choices, but our scope of action, simply as individuals, is very, very limited. So, you and I, we could choose to try and avoid palm oil, but in the first place, that's not going to actually make a huge amount of difference. In the second place, we might actually be investing our time and energy in things that could be possibly more destructive. Many of palm oils alternatives are equally terrible for the environment, soy bean oil, for instance, corn oil, fossil fuels. They all have negative impacts.

MAX HAIVEN: The only way we're going to overcome and meet these challenges, is if we develop some sort of political agency together to think through, how could we transform the world together? Not just through our individual consumer choices, but through social movements, through electing and supporting different forms of government, through organizing our lives differently. Because ultimately to overcome the world that we've created with palm oil and the world that palm oil has created, we need to change a lot of our habits. We need to move away from combustion engines, for instance, that are using agrofuels. We need to move away from the idea that oil and cooking oil should be cheap, that food should be artificially cheap for many of us. And we need to move back to ways of relocalizing agricultural production, of oils and other commodities.

MAX HAIVEN: We need to think again about how we organize global trade. But none of these can happen if we just limit ourselves to thinking about ourselves as consumers. And, so, that's the kind of horizon that I want to encourage us to move towards, with the book.

KAYTE YOUNG: I asked Max Haiven to read a passage from his book. It's from the chapter called "Whose Sacrifice?" and it speaks to that interconnectedness he just talked about.

MAX HAIVEN: The sacrifice transpires in the clinical anonymity of market relations. An increase in demand for snack foods in India triggers a chain of market decisions that see the forced displacement of an indigenous community in West Papua. And with it, the liquidation of their entire life way and cosmology. The anonymous demands of shareholders in a cosmetics firm for greater returns, leads to land-grabbing by entrepreneurial smallholders, or their hyper-exploitation of migrant workers. A subtle shift in policy to encourage markets to turn to bio-fuels, triggers a wave of peat land burning that releases massive amounts of carbon into the atmosphere, contributing to murderous impacts on global human and non-human populations via the vicissitudes of climate change.

KAYTE YOUNG: That's Max Haiven reading from his book Palm Oil: The Grease of Empire, published in April 2022. We'll be back with more from our conversation in just a moment.

KAYTE YOUNG: Kayte Young here. This is Earth Eats and my guest is Max Haiven, author of the book Palm Oil: The Grease of Empire. In the chapter called "Whose Surplus?", Haiven looks at palm oil as an ingredient in cheap, processed foods and how the French and other European governments have proposed what's known as the Nutella Tax. I asked him about it.

MAX HAIVEN: The idea was to artificially raise the price of these commodities to discourage consumption, often in the name of environmental and human rights protections in palm oil producing countries. But also, because of a growing recognition of the sort of ill-effects on people's health of consuming large amounts of processed foods with high concentrations of palm oil and other oils of that sort.

KAYTE YOUNG: And you point out that what measures like that really miss, is the complex relationship between fat and poverty.

MAX HAIVEN: To go back to the problem with the sort of green consumerism aspect of it, is that it presumes that you, as a consumer, have enough money or have enough time to educate yourself on making ethical purchases. And the reality is that increasingly, not only globally, but also within allegedly rich countries like the EU countries and the United States and Canada, there's a lot of incredibly poor people who are basically making it pay check to pay check. And have no choice except to consume the cheapest form of food and cosmetics they can. So, it doesn't help very much for us to say, "Oh, you shouldn't be buying palm oil related projects when, like, buying products with other oils is so much more expensive." And just to reiterate it, that's because we live in a world where there is a gross and vicious division of wealth, where a tiny proportion of people have incredible resources and the vast majority of people have very little.

MAX HAIVEN: So, something like ramen noodles, which I talk about in the book. This is a great example of a food that is enjoyed and consumed greatly by poor people typically. I mean, many of us enjoy it as a snack food who can afford to buy more expensive things. But for many families, that's what you give your kids for lunch because that's all you can afford. It's very cheap. Ramen noodles are made up of enriched wheat flour and palm oil, basically, and monosodium glutamates and sodium. So, it's a good example of how the green consumerism narrative is, very very limited. But it goes a little bit further than that too. Because one of the things that a number of scholars have been pointing out over the last few years, is that in a neoliberal era, where increasingly we're taught to think of ourselves exclusively as consumers and as sort of competitive individuals, trying to fight with one another to survive in a free market. Kind of this ideology that's been rampant since the 1980s and has led to kind of privatization and deregulation and more corporate freedoms and the growing inequality.

MAX HAIVEN: Within that mentality, the meaning of fat has also changed a great deal. I mean, that period has also seen the emergence of a mass media that's dedicated to these kind of glamorized images of extremely thin models. Which leads to a kind of fat phobia in society. But also fat has gone from being something that we associate with the kind of gluttonous wealthy who are consuming too much. Because those people typically can afford high quality foods and exercise regimens and plastic surgery. Instead, fat is increasingly associated with a kind of undeserving poor. People who are said to lack a kind of self-control, that not only means that they become heavier, but also means that they can't succeed in the economy.

MAX HAIVEN: So, classically in the United States, you have these kind of racist mythologies of sort of the welfare queen, that was introduced by Reagan in the 80s. Who's pictured as this kind of overweight, over-indulgent, racialized woman. Or you have these visions of in Europe, the kind of down and out working class who are just eating junk food all the time and are not taking care of themselves. These sort of classist and racist visions emerged within a context where we're all told to be kind of lean, mean fighting machines in a ruthless global economy. And as a result it prevents us from really recognizing that fat is actually a political issue. This is something that feminist scholars and activists have been pointing out for decades now. But it's become even more important in a moment where global nutrition is becoming so pivotal to the way that people live and die.

KAYTE YOUNG: I asked Haiven to explain how he sees fat as a political issue.

MAX HAIVEN: First on the level of body size and body image, we have high rates of mental ill health and self-harm that's related to people's negative body images, to begin with. And often those negative body images are associated with fat. But also we continue to imagine that the reason that people appear to be fat, is that they lack a certain amount of self-control, when in fact that's categorically not the case. This has been proven by many different scholarly areas, from nutrition to biochemistry to cultural studies. So, there's the sense that we're always looking, and this maybe ties back to some of the things we've been speaking about. We're always looking to kind of blame an individual. Sometimes we're looking to blame ourselves for not consuming the right types of foods, for not being a good green consumer, for not being a good ethical consumer.

MAX HAIVEN: Sometimes we're looking to blame poor people for their own poverty. We've been so habituated to individualist narratives that the problems of the world stem from bad people making bad decisions. So we can't see that in fact both fat and questions of palm oil, can only be addressed if we think holistically and act in a coordinated way at the level of society itself. So, the way to take care of the problems that we associate with fat which are people's ill health, is to make sure that we have a more even distribution of wealth, so that some people aren't suffering in poverty and can only afford foods that are bad for them. It would be to rethink the politics of edible oil and other forms of oil, fundamentally. It would be to reground people in community so that they can support one another, nutritionally, but also agriculturally. It would be to reconnect with the land. It would be to reconnect with a sense of what it means to be one species among many.

MAX HAIVEN: But all of these questions kind of get thrown off the table, to the extent that we just focus on the individual's poor nutritional decisions. In the book I point out there's a thing that the Ancient Greeks used to do called the Comedy of Innocence. Where they would make a sacrifice, they would create a situation in which an animal would accidentally, like a cow they wanted to slaughter, or a sheep they wanted to slaughter, would accidentally brush up against a holy altar. And the scene would be orchestrated so the animal could do nothing but bump up against the altar, and the animal doesn't know an altar from a tree. But then the Ancient Greeks would take this as evidence that the animal had elected to be slaughtered, or that the Gods had selected this animal to be slaughtered. And there's a very nice article by Nick Partyka about this in our present age looking at the prison system, that, you know, we set people up to fail in this society all the time.

MAX HAIVEN: We set them up to lead lives of poverty, ill health, criminalization. And then we have a kind of equal comedy, what he calls a comedy of guilt, to say, "Ah ha, this person now deserves everything they get." So, in the case of palm oil, in the limited sense, we say, "Oh, people made all of these bad choices with their health and why should we pay for their healthcare?" And, "They have only themselves to blame for being too heavy or having ill-health indicators." Meanwhile we don't see the broader system that set them up to be in that situation, and set so many people up to be in that situation. To move it around the world in the same context, it's like saying, why did those migrant workers choose to get on a boat from Sri Lanka or India, and go to Malaysia or Indonesia to be exploited in the palm oil plantations? They should have stayed home and started a app start-up or something like that. Which completely ignores the context that would force people to leave their homes or flee their homes, or force them into the situation where that was the only option available to them.

KAYTE YOUNG: We'll have to talk a lot about this, but I was just really surprised, and I have to say, pleased to see though that you named the body mass index as a pseudo-science.

MAX HAIVEN: This was new to me. When I was doing the research for the book, I was so shocked. But it really is. It's incredible that it's been so widely taken up.

KAYTE YOUNG: I just went to a doctor's office with my son the other day and saw it on the wall and while we were waiting, we looked at it.

MAX HAIVEN: Not only a fiction, but a fiction that, as a number of scholars have pointed out, was actually built on highly white supremacist notions of what, like, a body size should be and the meaning of fats and all sorts of things. So, yes, it's a terrible indicator.

KAYTE YOUNG: I would love to do a whole show on that. That's pretty interesting.

KAYTE YOUNG: You do definitely present a vision at the end of the book, and talk about some of the ways that we could be thinking about this differently.

MAX HAIVEN: Well, I'll start and I'll end with my vision, and I'll go a little detour in between. My vision is that the story of palm oil can be used to help us think about what it would mean to think as a global species. And we can no longer afford not to do so. We're a species that, in the interests of the continued power and influence of a ruling class, has been divided against itself. With each nation and many ethnicities within each nation, competing to avoid the worst effects of a crisis, of a system that we're caught up in. And we need to kind of get off that train and that task is huge. I mean, we're billions of people and we need to somehow coordinate a fair and just and sustainable system, but we do need to do it very soon. And my argument in the book is that in order to do that we need to be able to tell different stories about the world that we live in, and different stories about who we are. And I think those stories include a full accounting of our entanglement with other forms of life. Including the plants that produce palm oil and our impacts on, not only orangutans and the forests of Indonesia or Malaysia or Brazil, but also all the forms of life in those places as well.

MAX HAIVEN: And it also requires consideration of how we want to live together, and what we're willing to sacrifice, and what we would gain from really fundamentally and in a revolutionary way, transforming the way we live. I'll come back to that in a minute. I want to say first, that I'm not actually an expert on palm oil. I'm an anti-capitalist cultural and social critic. And I use palm oil as a way of getting at this thing which interests me, which is how do we tell a story as a global species about ourselves? I think the first step with the palm oil situation is, we should probably be listening to the people who know best. And there's two types of people that I think we really need to listen to. I mean, one of them are indigenous organizers, working people's organizers and community members in areas that are affected by palm oil.

MAX HAIVEN: These people have an in-depth understanding of not only what the palm oil industry does and how we could protect workers and environmental rights. They also have a very different vision of what the world could look like. So, I think those are the people we need to listen to first. The other thing is over the last 50 years, lots of people have sounded the alarm about this industry and what it does to people on the planet. Those people have been, at times, bullied and intimidated by the industry, at times simply ignored. If we just listen to the people who have categorical expertise on this, a lot would greatly improve. The problem is that often when regulatory bodies in the global north look for experts, they're given experts who work for the industry, or they're under a huge amount of pressure from the industry and also from the people-- the companies that buy palm oil.

MAX HAIVEN: So, essentially it's like climate change. The vast majority of experts are like, we need to wind this industry down and fundamentally transform it. But a small number of experts who have very specific vested interests are being listened to instead.

KAYTE YOUNG: There is this organization that you talk about, or a proposal called Just Transition.

MAX HAIVEN: So, Just Transition is an effort by a group of scholars and activists and NGO workers, who work extensively with indigenous groups and workers, organizations and communities. Mostly in South-East Asia, but also elsewhere. And based on years and years of consultation, they've come up with a plan about how you can move away from the kind of large plantation economy of palm oil, towards, yes, palm oil is grown and cultivated and refined and sold on global markets. But in ways that still protect environmental and human rights, and that place workers and indigenous people and peasants at the core of that process and make them the beneficiaries. It's a very nice plan. I'm not an expert in that level of political economy, so I don't have the kind of depth of assessment that many of my colleagues would. But it struck me as a very thoughtful and responsible way of going about trying to envision what it would mean to transition away from palm oil, as this quintessentially cheap commodity. And to rethink what it would mean to build global solidarity around a set of demands that are actually sustainable and humane and look towards the future.

MAX HAIVEN: My great hope for the book is that it'll contribute in some way, to work that's being done by people who are far more learned and wise than I am about palm oil. But really, again for me, palm oil is the character, but it's a story about a much larger set of global processes. It's about how global capitalism is not just an economic system, it's also a system of human relationships. And that those human relationships are global now, and if we want to have a better relationship with the planet and with one another, we need to really fundamentally shift our thinking. And I think, like, hopefully this book is a small part of efforts to move us in that direction. I think lots of people are doing that work in really phenomenal ways. In some ways, it's a very terrifying time. In some ways, it's a very exciting time as well.

KAYTE YOUNG: To conclude our conversation, I asked Max Haiven to read a passage from the first chapter of Palm Oil.

MAX HAIVEN: In the story of palm oil, we can catch a glimpse of the world as it is made and unmade. To read a world of palm oil as if it were our story, is to recognize what connects us and what divides us. My hope is that in paying attention to palm oil, we might exercise some shared narrative muscle, so long atrophied in this world of competitive individualism, so that some "we" emerges that can better know itself and act in concert to change our fate. If we made this world from palm oil, what else could we have made? What else might we yet make?

KAYTE YOUNG: That was Max Haiven, reading from his new book, Palm Oil: The Grease of Empire, released in April of 2022, from Pluto Press.

KAYTE YOUNG: Well, I want to thank you for writing the book and for the work that you're doing and also for talking to me.

MAX HAIVEN: Thank you so much. It's been a pleasure.

KAYTE YOUNG: Max Haiven is Research Chair at the Radical Imagination at Lakehead University in Ontario, Canada. He's also the author of Revenge Capitalism, released in 2020, and Art After Money, Money After Art, from 2018. Haiven teaches at Lakehead University, where he co-directs the ReImagining Value Action Lab.

KAYTE YOUNG: That's it for the show. Thanks for listening. We'll see you next time.The Earth Eats team includes Violet Baron, Eoban Binder, Alexis Carvajal, Alex Chambers, Mark Chilla, Toby Foster, Daniella Richardson, Samantha Schemenauer, Payton Whaley and Harvest Public Media.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week to Max Haiven and Xenia Benivolski.

KAYTE YOUNG: Earth Eats is produced and edited by me, Kayte Young. Our theme music is composed by Erin Toby and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from Universal Production Music. Our executive producer is Eric Bolstridge.