[Earth Eats Theme Music]

KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington Indiana, I'm Kayte Young and this is Earth Eats.

KEVIN COOK: Bloomington is known in the science world. If you say "Bloomington" people think fruit flies.

KAYTE YOUNG: This week on our show it's not exactly a Halloween story, but some might find it a little bit creepy. We're spending time in the kitchen of a science building on the campus of Indiana University, where they prepare food for a tiny organism that supports genetic research around the globe. It's fascinating stuff, at least to me it is. I hope you'll agree. Stay with us to find out.

KAYTE YOUNG: This is Earth Eats, I'm Kayte Young.

[music]

Everybody eats. It's not just a uniting principal for humans, but for every living thing. Even for the lovely fly. This week on Earth Eats, we're focusing on the diet of the fruit fly. You know that annoying pest that shows up in your kitchen usually in the summer, seems particularly interested in vinegar and bananas. Well, basically any fruit. That's the one. Most of us when we encounter a fruit fly are focused on keeping it out of our food. But what if it was your job to feed fruit flies? Meet Kevin Gabbard.

KEVIN GABBARD: I'm a media specialist, Indiana University, biology department.

KAYTE YOUNG: And how would you even go about doing that?

KEVIN GABBARD: (sound of water being poured) Okay well we're gonna mix all of our different ingredients in a big mixer first before we put it into the pot. So that we don't have clumps and such, cause that would be a disaster.

KAYTE YOUNG: And furthermore, why would you?

KEVIN GABBARD: We have what we call model organisms. There really aren't very many organisms that are easy to work with within a lab. And fruit flies are one of them.

KAYTE YOUNG: These are the questions we are exploring this week, in a science building, on the campus of Indiana University. I know it might sound strange for a food show to have an episode about fruit flies, but bear with me. They do show up in our kitchens, so that's food related. And when I found out there was a kitchen on the campus where I work, that is dedicated to making food for flies, I was intrigued. Let's talk to the chef Kevin Gabbert. His official title is Media Specialist. The food he makes is also known as a medium.

[Interviewing] How long have you been doing this?

KEVIN GABBARD: Over twelve years now.

KAYTE YOUNG: Has the recipe stayed mostly the same?

KEVIN GABBARD: The recipe stayed the same, the quantity keeps going up. The amount I have to make goes up, up, up.

KAYTE YOUNG: I met Kevin in the industrial kitchen located in a science building on the Indiana University campus in Bloomington. This was back in January back before the coronavirus hit the U.S., so no one was wearing masks. It's not a huge kitchen but I say industrial because it's got one of those big stainless-steel sinks with the sprayer nozzle on the faucet, floor drains, steel tables and metal racks, a giant floor mixer like you'd find in a commercial bakery, and a large self-contained stainless-steel vat installed next to the sink, with tubes and pumps and a big lid with a hinge. That's where they cook the fly food.

KEVIN GABBARD: A water jacketet pot, it's not steams heated but super-hot water heated.

KAYTE YOUNG: It's like an insulated with water.

KEVIN GABBARD: Exactly, exactly. And it holds like well today we'll make two hundred and thirty something liters of food in it and there's still room for it to not overflow at the top. So it's a pretty large pot. I think it's around 80 gallons I think.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay so it's a pot not a vat, and it has a thick wall, and that wall is filled with water which heats up and cooks the food. I know you're dying to know, what is the food? We'll get to that. But we might want to backup first and talk about why someone would have the job of Media Specialist, AKA chef to the flies. And what's at stake in getting the recipe right? Every time.

KEVIN COOK: My name is Kevin Cook. I'm a senior research scientist in Indiana University in the department of biology. This is the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, we distribute flies of the species Drosophila Melanogaster.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: Otherwise known as fruit flies.

KEVIN COOK: As fruit flies, yes.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: And are these the same kinds of flies that you might find buzzing around your kitchen in the summertime?

KEVIN COOK: Exactly the same kind of flies. They're find anywhere where there's fruit or vegetables. You'll find fruit flies.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Yeah, there are two Kevin’s in this story. And they're pretty much the two main voices you'll hear. To keep them straight, there's Keven Gabbard - he's the one who cooks the fly food. And there's Kevin Cook, and he's one of the codirectors of the center. So Kevin Cook is not the Kevin who cooks. Got it? Great, back to Kevin Cook.

KEVIN COOK: We're a repository for genetically characterized fruit flies. We distribute fruit flies around the world. We have, we support scientists in about 70 different countries, and about 3,000 different labs around the world, all of whom use these little fruit flies in their research.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: What kinds of research do these flies support? What types?

KEVIN COOK: So as biologists what we're interested in is you know what cells do, and why different, why some cells are different than other cells, and how cells talk to each other, and how they cooperate to form tissues and organs, and the sorts of things that go wrong with cells when you get a disease. So all of those things are controlled by turning genes on or turning genes off.

And as a biologist what you'd really like to have is an organism where you can turn on genes or turn off genes in particular cells, in particular tissues at will, so that you can see what genes do. And fruit flies are the best organism there is for doing this kind of research. We know more about the genes of fruit flies then we do any other animal, and the experimental genetics, the things you can do in lab with fruit flies are more sophisticated than you can with any other animal that you can work with in a laboratory.

People have call it 22,000 genes, we know what only a small handful of human genes do in detail. And so right now what the whole field of genetics is trying to do is to figure out what all of these genes do in the cell and why they're important and how they interact. And so we are now in kind of the golden age of figuring out what genes do. We know they exist because we know the sequences of genomes, but we don't have any idea functionally what a lot of these genes encode in the cell and their importance.

I think eventually if you really want to understand human biology, and you really want to understand how humans work at the cellular level, you're gonna have to figure out what all of those genes do, right? And the fact that a small organism like a fly shares so many genes with people tells you how you may figure out how human cells work. We'll figure it out by working on these model organisms, where we can do it easily.

At some level every animal cell works the same way. And so for a lot of research it doesn't really matter whether you're studying a cell, a process in a fly's cell or in a human cell because the process is the same. Right? So you want to work on, you want to use an organism that's easy to grow, cheap to grow, and reproduces quickly if you wanna do research efficiently and economically.

So what geneticists are interested in is these fundamental processes, and we can learn about them in flies and then it's just a hop skip and a jump to say it's the same process or the same thing in a human cell. So this is cross talk, where you learn about the processes in a fly and then you apply them in humans. But at the same time if you implicate a gene in a human disease, then you can find the same gene in a fly and work out the details of what it does in an organism that's easy to work on, because you can't experiment with people. Right?

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: So the Drosophila or the fruit fly is really important for genetic research, and Indiana University Bloomington is really important when it comes to supplying fruit fly strains to labs all over the road.

KEVIN COOK: Bloomington is known in the science world. If you say `"Bloomington", people think fruit flies, because who is a geneticist knows that you go to Bloomington for research resources related to Drosophila. So we're supporting a lot of science going on out there. And really important stuff. Really fundamental stuff that trickles down eventually, eventually makes it to human biology and human medicine, and then there's this feedback.

IU is really important for this corner of biology; we support a lot of people doing a lot of research around the world. We have research labs that work on fruit flies and then we have this repository that I help run. This center has been going here at IU for about 35 years. We started in 1986, there was a big repository for fruit flies at Cal Tech. The guy that was running it was retiring and so we moved the entire repository to IU and it's going here since. I have been here about 23 years. When the flies first moved here there were about 1,600 strains and we're up to about 77,000 strains now.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: Okay so those are kept here?

KEVIN COOK: Yes. Yes so we have two different labs on opposite sides of campus. We keep two copies of every strain so that if a strain dies at one lab that we'll have a backup at the other lab. And we can keep them going that way. We duplicate everything for safety. As a matter of fact we just opened the second lab across campus this last year, this last spring.

KAYTE YOUNG: So I would imagine that gets a little more complicated to maintain but maybe you just duplicate everything.

KEVIN COOK: We have a van now. We take food from one side of campus across to the other side of campus and then we bring the dirty dishes back to this side of campus and clean them up here. So it's a lot of work.

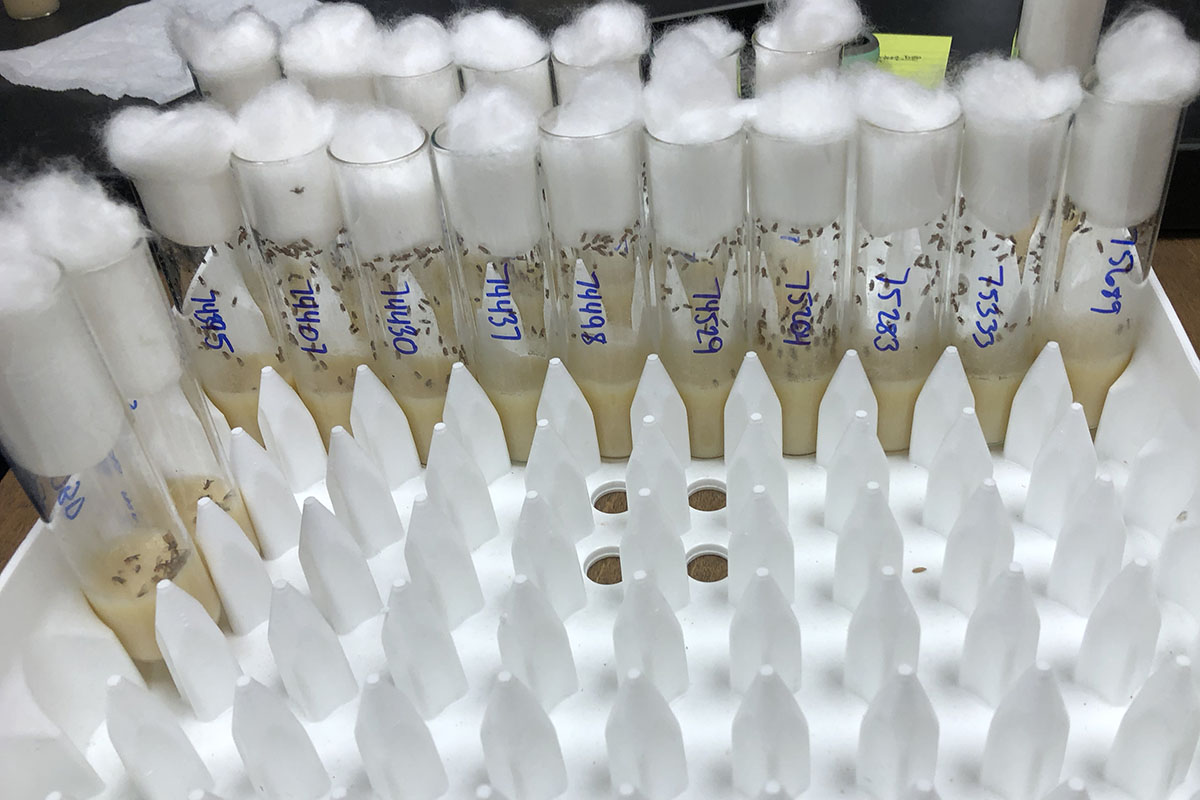

KAYTE YOUNG: The fly strains are kept in small glass vials, about an inch in diameter and maybe three inches tall. There's food in the bottom of the vial and the stopper made of rayon that looks like a tuft of white cotton. Each vial holds about a hundred flies. To keep them alive they need to be fed fresh food.

KEVIN COOK: So we have support facilities to keep this whole thing going, we have a media kitchen for making the food that you visited. And then we have a cleanup facility where we take all those dirty dishes, and we clean them up and just keep the whole thing going.

KAYTE YOUNG: There's so many moving parts to this. And so there's a dedicated staff that this is what they do, they come in and change the vials.

KEVIN COOK: Right, so we have about 65 people working for us, feeding flies. Now a lot of them are part time, but that still works out to about the equivalent of 25 full time people who are putting flies on fresh food every two weeks and allowing them to grow up and keeping this growing. So you know, you've got 77,000 strains maintained in duplicate and you're feeding them every two weeks and so it's a lot of work. That's a lot of work. We have a big staff.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: If you're just joining us we're talking with Kevin Cook. He's a senior scientist in biology at Indiana University. And he's a co-director of the Bloomington Drosophila center. Where they maintain strains of fruit flies for genetic research. After a short break we'll return to Kevin Gabbard in what’s known as the Drosophila media kitchen where they make the fly food. We'll also hear more background on the research the facility supports. Stay with us.

(Piano music)

I'm Kayte Young, this is Earth Eats. We're back with Kevin Gabbard in the kitchen where the fly food is made. Kevin makes a batch of food three days a week, so every other day. On the days he makes food, he gets started in the morning.

[Interviewing] So what are your ingredients?

KEVIN GABBARD: This is soy flour. The other ingredients will be yeast, it's an inactive dry yeast for flavor. They like the flavor.

KAYTE YOUNG: And why would flavor be important?

KEVIN GABBARD: So that they'll eat it (laughs). It's the only thing in the tube, the actual vial that will give them nutrition and substance while they're laying eggs and doing all the different things they're wanting to do. Strainer - we strain everything too, so make sure nothing has lumps after we... cause once it goes through everything, it cooks, if there's lumps and it goes through the filler, it's over there that has small holes in it. And any kind of lump would clog the filler then all of the sudden you have one vial that is not filling in each tray which would be bad. So that's why you do that.

KAYTE YOUNG: So what have you got there?

KEVIN GABBARD: This is corn syrup. Just run-of-the-mill light corn syrup. And that's another thing that they like is sweet. So the corn syrup adds a really nice touch to the between the yeast and the soy and then the corn meal is where they get a lot of the nutrients from, but it doesn't have a lot of the flavor, so they put the other different ingredients in it. When it first started there were other ingredients in it also, but they've kind of cut it back to where it's just these simple ones. They learned that they didn't need... at one point they used molasses. Well, that's expensive and it's not really needed. You know they're not that picky. You know, so.

KAYTE YOUNG: So some of the ingredients you're weighing and some of them you're just measuring in these kinds of food grade buckets.

KEVIN GABBARD: Right, right. Yeah, everything is weighed out and measured.

KAYTE YOUNG: So how much corn syrup goes in a batch?

KEVIN GABBARD: In this batch it'll be I think 17 liters.

KAYTE YOUNG: Now do you have to follow all of the food safety rules or does this not have to be quite as sterile?

KEVIN GABBARD: No. The short answer is no I don't have to because it's not for human consumption. We keep everything as clean as we can. You know with everything like that. So yes you could eat in this kitchen, but we're not held to that standard. But everything here's edible. There's nothing here that you know... professors in the past have ate the food, just so they could say to people what it tastes like. I'm not one of them. I mean I'm sure it tastes fine, but I have no desire to eat it.

KAYTE YOUNG: Smells like brewers.

KEVIN GABBARD: Yeah, yup. I used to tease them because they used to use malt, and then the yeast and people used to say, "Oh we always make beer down here" Which it's inactive, the yeast is and stuff, but it's just a joke.

This is probiotic acid, it's a food grade preservative. It keeps the food from molding, gives it longer time. You know a longer shelf life. Without this it probably wouldn't last half the time that it lasts now.

(Sound of liquid being poured into a container)

KAYTE YOUNG: Smells of more like test tubes.

KEVIN GABBARD: Yeah, graduated cylinders. And you'll see them all over the building.

KAYTE YOUNG: So you marked those.

KEVIN GABBARD: I have to mark them before I dispose of them to let them know that they've been rinsed. It's a safety thing for the custodians when they pick them up. Cause I'll put it into the glass bucket, but they need to know that they've been rinsed out.

KAYTE YOUNG: That's the only ingredient so far that doesn't smell so good.

KEVIN GABBARD: No and this is an ingredient that if it gets on your skin it'll burn you, and you don't want to drink it. You know because it is a preservative.

KAYTE YOUNG: So you're basically mixing these dry ingredients thoroughly with water so that...

KEVIN GABBARD: Right. And then so you'll see I'll run it through the strainers so there's no lumps in it. Cause when we pour it in the pot we don't want any lumps in there. Some of them would probably cook out but anything that doesn't cook out, then once again it would possibly clog one of the holes in the filler. And then we're fighting that all day.

KAYTE YOUNG: Sounds like that's happened before.

KEVIN GABBARD: It has, it has. Even on... even though you try your best, sometimes it happens.

KAYTE YOUNG: So the soy looks like a... almost like a consistency of a pancake batter at this point.

KEVIN GABBARD: Right. I'm gonna weigh out the cornmeal and put them in these buckets. Probably the most weight other than water is the major ingredient into the mix is cornmeal. It equals out to be just a little over 35 pounds of cornmeal a day, so that's a lot. I want to put another hundred liters of water in. What we call the batcher, and what it does it batches a hundred liters of water into the pot. Hot water.

(Sound of water pouring into a large container)

So we'll put in the second batch in now, and I turned on the pot. Now you can kind of hear it humming, it'll be humming and that jackets filled full of that hot water and it's circulating through those two white pipes, insulated pipes there. It comes in and circulates through and that's how the pot heats.

At this size is a lot of things are done through steam which would be great except the steam on campus is not so reliable at times, and if it would go down at some point then we couldn't make food. So they've got what they call a tankless hot water heater on the other side of this wall that heats it up, hot enough to boil. And that's how we heat the food.

This is an industrial grade cement stirrer. And what it does it stirs the water. When they built this pot it was meant to have this on it so it would stir it. It's better than grandma with the spoon and the kitchen, because you know this is the only way we can really stir it other than to get a boat paddle and... (laughs). That stirs it continuously.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Kevin premixes most of the dry ingredients with water before pouring them into the giant pot. He takes all necessary measures to avoid clumps. He mixes some of it in the giant mixer...

[INTERVIEWING] Scraping the sides of the mixer just like you have to do for cookie dough.

KEVIN GABBARD: Yes. This is agar. This the magic potion that makes it all gel. Come to think of it like jello, it is a gelatin. It's a seaweed-based gelatin.

KAYTE YOUNG: See now that's the one I would be worried about clumping because I know that gels can really do that.

KEVIN GABBARD: They can, and this will, but as long as you get it in before it gets to a boiling temperature it's good about mixing up. And I always check to make sure, but I've never had it to where it didn't mix.

KAYTE YOUNG: And you're putting it in there just with the water, so your kind of letting it get mixed up before you add.

KEVIN GABBARD: Before it ever comes to a boil it'll be completely mixed in there. And without it, it'll still be runny and slushy and stuff. Cause it has to set up. It's just that little bit will in that pot will be huge and you'll see how important that is to have that in there.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: He premixes five separate buckets of cornmeal with water.

KEVIN GABBARD: For the cornmeal, 8 liters in each bucket for the cornmeal and then I'll stir it so that it's mixed up. It mixes up really well, it's cornmeal you know. So it doesn't clump real bad.

I use a spoon first to stir it, then when I got to mix and put it in the pot I use my hand. Cause you can feel with your hand if there's any clumps in it.

(Sound of media sloshing as it is mixed)

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: So now it smells like you're making grits.

KEVIN GABBARD: Yup. (inaudible) That's pretty much, yeast soy mixture. Now for the corn syrup.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Okay so you've got your protein with the soy, cornmeal for a starch, some yeast for flavor, some sweetness from the corn syrup and a thickening agent. It's sounding like a somewhat recognizable porridge you could say. By the end of the process I ask Kevin if he could give us a quick recap of the recipe.

KEVIN GABBARD: Like today we went through 213 of water plus 10% cause it's wintertime. And in the wintertime - I didn't bring that up, in the winter time, actually it's June 27th, in the wintertime you add 10% more water because it evaporates so much more being dry.

And then soy is 2210, yeast 1912 x 2, so we had two buckets of that, and then you know 32-30 for each bucket of five, 17 liters of what used to be (inaudible) it's just corn syrup now, and then that's my acid amount.

Agar is different because agar has different gel strengths. Every time I get an agar in it may have a different gel strength then the time before. And then there's a formula to figure out what gel strength it is, and then I have it on the lid here. Like today we did 1324 grams of agar for that size of pot, but it could go up or down depending on this is an 850 gel, it goes up 1100 and 850 is usually on the lower end of anything I get. I haven't had anything over 800 for several years.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: I uh... guess it's not that straight forward. Well he says you can find the recipe on the stock center's website. We'll link to it on ours, EarthEats.org

KEVIN GABBARD: ...now there's some certain agars like that they use upstairs for media that stays consistent...

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: While the corn mush cooks, it only takes about 15 minutes, I follow the sound of clinking glass into the next room. It's a storeroom with stacks of cardboard boxes stamped with a large green fruit fly graphic carrying a product named simply Drosophila Vials from a brand called Fly Stuff. There's bakers' racks lined with tray upon tray of empty glass vials. Against one wall is a small desk where Iain Vollman moving clean glass vials from one open tray into an orderly gridded tray that holds 100 glass vials.

IAIN VOLLMAN: You want to know what I am doing?

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: Sure, what are you doing?

IAIN VOLLMAN: Racking vials of course. I do this every morning here. This is how we usually get our fly food in. Normally we get dirty vials such as these right here which cannot be used so normally I put them here, this goes back up with the others so they can be cleaned out.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: So you're organizing them but you're also checking to make sure there's no dirty ones.

IAIN VOLLMAN: Correct. Empty trays go here and stack up to up here and then they get put outside on the shelves.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Ian is prepping the vials to be filled with the food, for the flies.

(Sound of clinking continues as Iain sorts the vials)

Back in the kitchen, Kevin is cleaning up. Though he has been cleaning up as he goes throughout the whole process.

KEVIN GABBARD: As you can see I don't use any soap or anything on these buckets or anything because soap kills the flies so, if something would happen it wouldn't get rinsed well enough it would kill them.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: So I guess they have to be careful with how they clean the vials too.

KEVIN GABBARD: Yes, yes, they use an industrial dishwashing detergent on those. And then there's also an antispotting agent they also use, but both of those things are okay for the flies, it won't kill them. It's actual soap-soap. What it does it keeps them from breathing. It basically suffocates them, soap will. That's why when you see traps a lot of the time it's vinegar with a little bit of soap in it.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTEVIEWING]: Yeah I was just thinking that.

KEVIN GABBARD: Yeah so that's the reason we stay away from it down here.

(Sound of a large volume of water being poured out)

I use the same detergent they use to clean the vials to clean the pot with, and the hoses and stuff out with, because it's safe.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Once the kettle of corn mush is cooked and ready for the filler, Kevin sets up the machine.

[Interviewing] So this is called a Drosso Filler?

KEVIN GABBARD: Yes, and this is what they call a Maxx. And what the Maxx does, you push a button and through air compression it moves the plate, it used to before they started making this you had to do it all by hand with a big handle. And you would do every one of them, every single tray by moving the lever back and forth. Now you just push a button and it’s kind of takes a little bit off your... the wear and tear on your arm all day long. Well not all day long, but while you're doing it.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVEIWING]: But still it's not that automated, you have to put each tray in there right?

KEVIN GABBARD: Right, yes. That's the only automated part about it, the rest of it's all human (laughs) in and out, pump it, Iain comes over and then he'll cover them and then we'll put them on the drying racks, so it'll sit and dry for several hours. So and then we put the cheese cloth on to keep any drosophila that would've actually be in here, which there shouldn't be any in here, but if one would get in or a common housefly or something, it keeps it from getting into the vial and laying eggs.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVEIWING]: Yeah.

KEVIN GABBARD: That's very important when they have an experiment going on and all of the sudden a larvae hatches and it's a house fly or some other insect that they didn't want in there. So that's the reason we have to do that.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Kevin also mentioned that they have no pest control in the building. They can't risk it with the fly population. The food which by now is a pale golden smooth mixture is the consistency of the thin pancake batter, no lumps, Kevin was careful. And that batter gets pumped through clear flexible piping into a small square hopper over the filling mechanism. Kevin slides a tray into the bottom of the machine. Lines it up with the holes under the hopper, presses a button, and the filler drops batter into the one hundred vials in the tray. He releases when the right amount is reached. He slides the tray of filled vials out and Iain places a square cheese cloth over it and moves it to a rack. And repeat.

IAIN VOLLMAN: I use this down here, cover these with the clothes and then put them on this cart, (inaudible) or else these overflow.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVEIWING]: So you don't hold that down for a certain amount of time, it does the exact amount?

KEVIN GABBARD: No, no it's not. You have to do it all in your head. It's not always that easy because sometimes, you know, it gets away from you or something and you get a little bit more in there than you want or something but...

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVEIWING]: You guys are like a mini factory.

KEVIN GABBARD: It is!

IAIN VOLLMAN: Mhm. We are the machines.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVEIWING]: It's such a small amount that goes in each vial too. I expected them to be filled up, I don't know.

KEVIN GABBARD: No, no. They have to have move to around and live their little lives in there. You know, they eat.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVEIWING]: And I can see that it could get repetitive and not seem so exciting, but does it feel... how does it feel to know that you're supporting this research, or does that play into it at all?

KEVIN GABBARD: Oh yes, it's very rewarding. Especially when you see how many there are and how much we do, it's very rewarding.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVEIWING]: There are certain mistakes that you cannot make, or you endanger the stock.

KEVIN GABBARD: Right, right. Exactly. And on the food end if I forget an ingredient, definitely don't like to forget to put like the preservative in, that would really mess things up if I would pump all this food out and not have preservative in it. It's not going to last half as long. So something small like that would really mess things up. Important aspects to making food.

And there's a lot more important things than the food and stuff, upstairs to them of course. But that's something that I want for them to not have to worry about. You know something they don't even have to think about, it's just food you know.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Kevin hopes that the scientists will take the fly food he makes for granted. Something they don't have to think about. While the fly food is setting up seems like a good time for a break. I headed back to my office on the other side of campus. After a short break in this program, we'll return to the fruit fly kitchen for the final steps in the process. Hang in there.

(Piano music)

Kayte Young here, this is Earth Eats, and we're spending this hour in an unusual type of kitchen. This one is for science. Kevin Gabbard is the chef for over 70,000 strains of Drosophila melanogaster, otherwise known as the common fruit fly. So far we've been through the measuring, mixing, cooking and dispensing of the food. It's a sort of corn based thin porridge with a gelling agent that allows it to set up once it's dispensed into the vials where the flies are kept. Each vial holds about 100 flies, and they need to be moved to fresh food every two weeks. So every other day Kevin Gabbert and his assistant, Iain Vollman, fill 300 trays, about 30,000 vials to keep the stock center... well stocked.

I returned to the kitchen a few hours after the food was dispensed. Now it's time to flip the trays and take them to the upper floors. They take a tray of filled vials, remove the cheese cloth and cover the vials with the pressing seal, just the regular household variety.

KEVIN GABBARD: Push down so that it adheres to the glass and then we put another tray over top of it then flip it over. So that the food is at the top and gravity holds the vials to the bottom of the tray against the press and seal to seal it off.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVEIWING]: And the food has setup so it's solid.

KEVIN GABBARD: Right. And once again if we hadn't used like an agar or something, what would happen, this food would just start running down or just bloop - fall right to the bottom once we flip them.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Now any time there's cooking there's going to be dirty dishes. In this case there's the cleanup from making the food, Kevin keeps up with that as he goes along, always. And while the food is cooking, or while the food is setting up in the vials, he gets the whole kitchen clean and set up for the next time they cook. But then there's another set of dishes that need to be washed. And we'll get to that. Right after the vials of fresh food are delivered to their destinations.

Kevin let me follow him on the delivery. The vials go upstairs, some of them go into labs where scientists are doing research. The lab I peeked into has a long counter with three scientists peering into microscopes. They're surrounded by small collections of vials, filled with flies, hungry for fresh food no doubt. The biologists will move the flies they're working with into the vials with the new food.

[INTERVIEWING] I'm doing a radio show.

BIOLIGIST: I see! (laughs)

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVEIWING]: So just following him up here for a delivery.

BIOLIGIST: Okay, sure!

KAYTE YOUNG: Their final destination

BIOLIGIST: (laughs)

KAYTE YOUNG: Happy customers

BIOLIGIST: (Laughs)

KAYTE YOUNG: Thank you, sorry to intrude.

SCIENTIST: No problem!

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: But most of the vials go to the walk-in cooler where they'll be retrieved as needed by the flippers, also known as stock keepers. These are the people whose sole job is to feed the drosophila. The fruit fly strains that make up the vast collection at the stock center.

KEVIN GABBARD: You know they can only have so many in here, well since they split it between that and mesh, it's not as bad. But used to when they were all here, you know, then they split half of them over there, so it's not so bad. But when they were all here you could only get so many people to come in the daytime, there was not room to sit down and flip. And then some people had kids or other jobs and they would come in the evenings and flip. I mean there was people here probably around the clock at one point in time.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: Just to keep up

KEVIN GABBARD: Yeah.

CAROL SYLVESTER: Hi

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: Hello!

KEVIN GABBARD: This is Kayte, she's with WFIU, she's doing a story about the fly food.

CAROL SYLVESTER: Hi Kayte!

KAYTE YOUNG: Hi

CAROL SYLVESTER: I love your hair.

KAYTE YOUNG: Thank you (laughs) it's a food show. But I thought it was interesting that you guys are feeding the flies all day.

CAROL SYLVESTER: Yeah we had to clarify when we say "do you want some food" what we're getting. Fly food.

KAYTE YOUNG: So what is the process of flipping them?

CAROL SYLVESTER: Yeah, oh, you just have to take the oldest vial and flip the flies onto new food.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay so you take out the rayon.

CAROL SYLVESTER: Yeah, I take out the rayon, flip the vial onto the new vial, and then replug it. And you get rid of the oldest vial, and then you just turn around. And then they have special food for if they are sick, there's German food with more nutrition and I guess more yeast in it.

KAYTE YOUNG: Is that pumpkin?

CAROL SYLVESTER: No not pumpkin. Some... Mr. Coffin has the pumpkin food. And then this one has like antibiotics put in it, so if there's bacteria you can use that. So I'm feeding all the sick flies, so I have to have that in here.

KAYTE YOUNG: How (laughs) how many of these do you think you do in a day?

CAROL SYLVESTER: Well Andrea's doing 11 trays today. I don't do as many because I'm doing the sicker flies, they take longer. So there are about 60 stocks in each tray. So. She's gonna flip over 600 stocks today.

KAYTE YOUNG: Do you ever have any flies that don't want to come out, or are they all...?

CAROL SYLVESTER: Yes, sometimes they're stuck in the food or on the side of the vial. And you can let them crawl up because they like to go toward the light, so if you hold it under the light they'll crawl up. And then you'll have ones that come out too fast and they escape. So we have fly traps for all that. We're supposed to try to keep them from getting out of the building which is a little hard when you have little winged things.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah.

CAROL SYLVESTER: (laughs)

KAYTE YOUNG: What is your name?

CAROL SYLVESTER: Carol Sylvester.

KAYTE YOUNG: Thank you so much Carol, I really appreciate it. It was great to meet you and to see what you're doing.

CAROL SYLVESTER: Nice to meet you too!

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: So Kevin Gabbard makes the standard fly food formula. But there are special foods made in smaller batches for particular types of research. I had heard about the food made with pumpkin; in fact it was what got me interested in this story in the first place.

The drosophila stocks with the expansive list of individual strains are used in research in our campus. They're also available for the larger scientific community and they're shipped all over the world. They use plastic vials for shipping. Kevin Gabbard explains that this is to ensure that they don't break in transit. But the fly strains in the Bloomington drosophila stock center are maintained in glass vials. They're reusable, ecofriendly, and more economical than plastic. But that means dishwashing. A lot of dishwashing.

Iain took me to the dishwashing room for a tour.

IAIN VOLLMAN: First of all, this is where other trays go that Kevin usually brings up. Here is where some of the other fly food is with flies in them. This cart is for when we need to take them inside. Now this is where we go inside. Okay, here you go.

(Sound of rock music)

IAIN VOLLMAN: Okay guys... Alright, here is...

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: Hi

IAIN VOLLMAN: (inaudible) This is Bennett.

BENNETT: (inaudible)

IAIN VOLLMAN: Best guy I know here.

BENNETT: I try to be.

IAIN VOLLMAN: And this fine lady here is our interviewer for today

BENNETT: How are you doing?

KAYTE YOUNG: Nice to meet you.

BENNETT: Nice to meet you.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: He showed me the auto cleaver.

IAIN VOLLMAN: Which goes up to extreme heat levels for a certain amount of time.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: To sterilize?

IAIN VOLLMAN: Yeah.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay.

IAIN VOLLMAN: Then we take them out to take out the cotton over here. Then we spray them out over here to get the gunk out. Fill up to soak overnight. Then we flush them out. After that's done we put them in the washers. They go for a certain amount of time. After that's done we put them in the dryers to let them dry out for a certain amount of time. Then we rack them, and then it goes back down, which is a simple cycle.

KAYTE YOUNG: And then you rack them into those trays.

IAIN VOLLMAN: Of course. So I guess that is...

KAYTE YOUNG: So there's three dryers?

IAIN VOLLMAN: Yes.

KAYTE YOUNG: Alright.

I'm doing a radio story, mostly about the food.

BENNETT: Oh really?

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah

BENNETT: Cool

KAYTE YOUNG: I just think it's interesting that there's a whole operation to feed the flies.

BENNETT: Oh man, especially to think that employs several people. Like full time benefits, everything, all for the sake of research for flies for drosophila. It's crazy to think, it's like they're doing research and while we're likely the kind of lesser knowns that help, each assistant, TJ and Erick, everything just goes to help research. It is kind of remarkable to think about.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yup, yup. Alright.

IAIN VOLLMAN: Endless possibility for us.

KAYTE YOUNG: Well thank you I appreciate the tour and yeah.

[NARRATING] It is truly amazing to have this crew working to maintain this valuable resource for the scientific community. Let's return to my conversation with Kevin Cook, codirector of the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, who we spoke with earlier. After hearing about the special treatment the sick flies were getting from Carol Sylvester, I had a question for Dr. Cook.

[Interviewing] How would you be able to tell if one was not doing well?

KEVIN COOK: Well you're really looking at an ecosystem. Right? You have a population of flies in a vial, and the little larvae are eating the food. And you're judging the health of the culture by how many flies are in the culture, how many eggs they're laying, how many larvae are in the food, and just generally how robustly the population is growing.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: That makes sense to me, I'm a beekeeper and that's definitely the way. You're not looking at an individual bee to see how they're doing; you're looking at what's happening. How many eggs are getting laid, how quickly... like yeah.

[NARRATING] Kevin Cook thought it might be helpful to go over the lifecycle of a fly.

KEVIN COOK: So the way the cultures work is that females will lay eggs on the surface of the food. And in about 24 hours the egg will develop from a single cell to a little larva that has all of its organ systems, it's brain, everything necessary for crawling around and eating.

It'll hatch from that egg and will start eating the food. And (it) will grow so that it goes from about the smallest thing you can see with your naked eye to a larva that is about the size of a small grain of rice over about four days. So an incredible increase in volume and size. And after the end of, after about five days the larva will crawl up on the side of that glass vial and it's outside, it's skin will harden to make the outside of the pupil case, the chrysalis if you will. And that fly will metamorphose inside that pupil case over the next five days.

So it will turn from something that looks like a little worm, a little maggot, to what you think of as a fly over the course of five days. Then it'll close, it will come out of that pupil case, crawl out, expand its wings, and it's an adult. Within about 8-10 hours after it crawls out of the pupil case, it's ready to mate and start the whole process over again.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: A few hours you said?

KEVIN COOK: Adolescence lasts about 8 hours in a fruit fly. And so this is why they're really good to use in lab because these guys are built for speed. They really develop fast. If you think about how long it takes most animals to grow, you know 10 days is really fast and you're talking about not only development but you're talking about development plus metamorphosis over that 10-day span.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: So I can see why that would be so useful to do kind of multigenerational, you can do multigenerational in a month.

KEVIN COOK: Right. We can get a generation every two weeks, if you really push it.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: I asked him for an example of well-known research that fruit fly experimentation has supported.

KEVIN COOK: Well going back historically, all of the details of how inheritance works were worked out in fruit flies. So if you understand that genes are on chromosomes, that was figure out in fruit flies. If you understand that things like x-rays cause mutations, and mutations cause abnormal traits, all of that was figured out in fruit flies in the first place.

That's historically. In more recent times the understanding about how genes contribute to development and all of those biochemical and signaling pathways inside the cell that are necessary for development from an egg to an adult, a lot of those details were worked out in fruit flies.

There was a Nobel prize recently for figuring out circadian rhythms, you know when you wake up, when you go to sleep, all of that was worked out in fruit flies. A recent Nobel prize was for how immunity works at the level of individual cells, and a lot of that information was worked out in fruit flies.

And so you've got a huge long history of really important discoveries having been made in fruit flies. And the principals were worked out first in this humble little organism, and then taken and added to and explored in mammals, and eventually in people. So fruit flies are where it starts and gets built on from that point on.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Nobel prizes, our understanding of human development? Big stuff from a little fly.

KEVIN COOK: At any one time we're growing about 308,000 vials of flies between our two facilities. And if you figure there's about 100 flies per vial, we have about 31 million flies on the Bloomington campus at any one time.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: They're not all in this building, but half of them.

KEVIN COOK: All of them in this building? (laughs)

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: Well as we were sitting here talking I did notice that there was one buzzing around (laughs)

KEVIN COOK: There aren't many escapees considering how many flies we have around. Stock keepers do a really good job of maintaining the cultures in a pure state and not letting those escape, get into other variables. It's astoundingly low considering how many strains we have growing.

(Guitar music)

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Though the Bloomington Drosophila Center had to make many changes due to COVID-19 restrictions, the staff are classified as essential personnel. Kevin Gabbard and the stock keepers and dishwashers have continued to maintain the flies at the stock center. They did have to stop shipping operations for a while, but they're back up and running with significant delays.

Thanks for sticking with me through this story of fruit flies and the people who feed them. If you have thoughts to share, drop us a line - EarthEats@gmail.com. Or send us a direct message on social media, you can find us @EarthEats. And I want to strongly encourage you to go to our website this week and look at the photos of the Drosophila Center, they really complete the story - EarthEats.org.

(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

That's it for our show this week, take care.

RENEE REED: Earth Eats is prodcuced and edited by Kayte Young with help from Eobon Binder, Alex Chambers Mark Chilla, Abraham Hill, Daniella Richardson, Payton Whaley, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week to Kevin Gabbard, Kevin Cook, Iain Vollman, Carol Sylvester and everyone at the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center.

RENEE REED: Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from the artists at Universal Productions Music. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey.