Gas utilities and cooking stove manufacturers knew for decades that burners could be made that emit less pollution in homes, but they chose not to. That may may be about to change. (Sean Gladwell/Getty Images)

The heated debate over regulating gas stoves is really about the burners in those appliances. That's where natural gas, a fossil fuel, is combusted and air pollution is released into homes.

Four decades ago, the gas industry and appliance manufacturers developed a partial solution for this problem. They created a cleaner and more efficient burner. But you can't buy ranges with those burners because the industry never manufactured those appliances for sale.

Appliance manufacturers and gas industry allies say there are reasons for that: these burners cost more, are less durable, harder to clean, and they didn't see consumer demand for them.

But now the industry appears ready to revisit the humble gas burner. The Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) is investigating whether gas stoves need tighter regulations to protect human health. One commissioner even left open the possibility of banning sales of new gas stoves.

This week, the Department of Energy (DOE) proposed rules that would require all stoves to be more energy efficient. If approved, more than half the gas cooktop market today wouldn't qualify under the new requirements, according to the DOE. The proposed regulations would take effect for sales of new stoves in 2027.

Even if the federal government only tightens regulations on gas stoves, that would boost efforts from climate activists who want Americans to switch from gas to electric appliances and heaters. Studies from Princeton University, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the National Academy of Sciences, find that zeroing out greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. by 2050 will require electrifying buildings, making appliances more efficient, and powering them mostly with emission-free sources like renewable energy.

A cleaner burner, but without a blue flame

In the 1980s indoor air quality was in the news, and the CPSC was taking aim at another home appliance that burns fossil fuels: kerosene heaters. Sales were increasing, and regulators grew concerned, because the heaters emitted harmful pollution into homes, mainly nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide.

The EPA says both pollutants can cause breathing problems, especially for people with asthma. And nitrogen dioxide, at higher levels and over longer periods, may contribute to developing asthma.

The natural gas industry saw regulators' interest and worried the CPSC might come for gas cooking stoves next, according to a 1984 Science News article. That prompted two industry research groups to begin working on burner improvements.

Out of that process emerged a "jet-powered infrared gas-range burner."

Instead of the iconic blue flame that you normally see at a gas stove, the infrared burner had "a flat ceramic plate... honeycombed with window-screen-like perforations," according to the article. Air and fuel burned as they were sent across the plate and ignited bright red in a way that makes the flame itself difficult to see.

This infrared burner consumed about 40% less natural gas to reach cooking temperatures and emitted 40% less nitrogen oxides. The Science News article said designers touted another benefit of the infrared burner: a kitchen stays cooler because more energy goes into the cooking vessel instead of the room.

A Pennsylvania-based stove manufacturer, Caloric Corporation, expressed interest in the infrared burner. That company is no longer in business and was absorbed into Whirlpool Corporation, which did not respond to multiple inquiries about why the burner was never offered in retail stoves.

Another company involved in developing the infrared burner, Thermo Electron Corporation, is now called Thermo Fisher Scientific. A spokesperson says the company couldn't speak to the infrared burner development, and that the process might have been led by an independent researcher.

"I'm sure the cost of that burner was probably significantly more than the existing technology," says Frank Johnson, research and development manager at GTI Energy in Des Plaines, Ill. The non-profit organization used to be called the Gas Technology Institute and is a research group closely tied to the gas industry.

Johnson says he doesn't know exactly how much more the burners would cost, because the, "technology has never been fully developed into a working range burner."

Kitchen range makers, such as Wolf, do offer infrared burners for charbroilers and griddles but not for stovetop or oven burners. Sub-Zero Group, which owns Wolf, did not respond to NPR's questions.

Johnson delivered a warning to high-end manufacturers at an industry conference in Minneapolis last September, according to a recording of the event NPR had access to: "The days of paying $6 for a burner on a $7,000 range may be over."

Gas utilities are under pressure

Both stove manufacturers and gas utilities face increasing scrutiny as scientific evidence accumulates that shows having a gas stove in the home may affect health, especially for children and people with breathing problems.

Nitrogen dioxide is the big concern for health experts these days. Because of nitrogen dioxide emissions, the American Public Health Association labels gas cooking stoves "a public health concern," and the American Medical Association warns that cooking with gas increases the risk of childhood asthma.

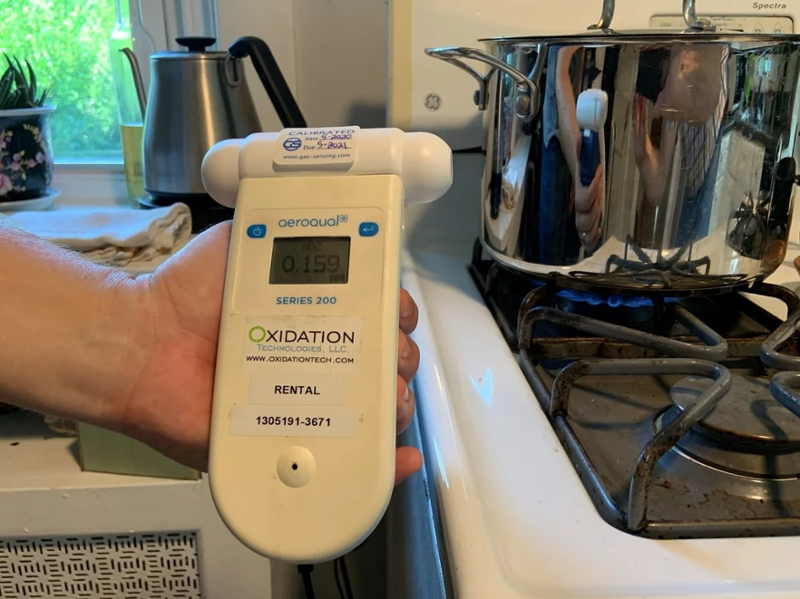

A nitrogen dioxide air monitor in a Philadelphia kitchen on July 16, 2021 shows 0.159 parts per million, or 159 parts per billion. That's above the World Health Organization hourly guideline of 106 ppb.(Jeff Brady/NPR)

A recent peer-reviewed paper found that more than 12.7% "of current childhood asthma in the U.S. is attributable to gas stove use." The gas utility industry pushed back on this latest study, which was funded by RMI, an environmental organization that encourages people to switch from gas to electric appliances.

"Organizations that are making these allegations are relying on reports that did not test natural gas stoves and have ignored research that found no association between gas stoves and asthma," wrote American Gas Association (AGA) President Karen Harbert in a statement to NPR.

The AGA often tries to equate emissions from fossil fuel combustion to cooking fumes. Harbert pointed to research GTI Energy conducted last year, which compared electric and gas stoves and showed, "no difference in their particulate emissions."

But particulate emissions from cooking are different from combustion emissions that come with burning natural gas. And when members of the industry talk amongst themselves, they are much clearer about that distinction.

In a presentation two years ago, the AGA's Ted Williams cautioned colleagues not to discuss ventilation of combustion emissions, because not everyone with a gas stove has a hood that vents outdoors.

"[G]as cooking does generate indoor air emissions of contaminants, including carbon monoxide, oxides of nitrogen, trace amounts of materials such as formaldehyde and so forth," said Williams in the 2020 webinar material provided to NPR. At the time, Williams was AGA's senior director for codes and standards.

"But recognizing that, it's not an issue that's going to be easy to paper over, because... these products do have emissions," said Williams.

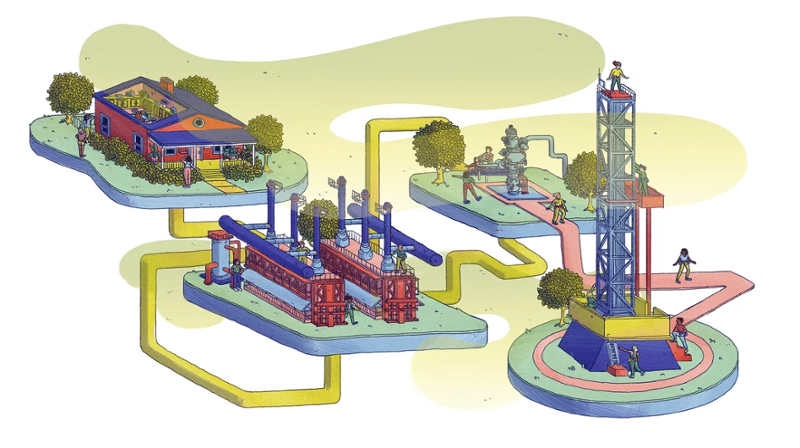

Gas stoves emit pollution into your house and they are connected to a production and supply system that leaks the powerful greenhouse gas methane during drilling, fracking, processing and transport.(Meredith Miotke for NPR)

Consumers aren't aware of gas stove hazards

For nitrogen dioxide, specifically, the EPA recommends reducing exposure by installing and using over a gas stove an exhaust fan that's vented outdoors. But that message isn't reaching consumers.

"There isn't much information available for people about the potential health risks of using a gas stove or the need for ventilation," says Matt Casale, director of environment campaigns at the United States Public Interest Research Group (US PIRG).