(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington Indiana, I'm Kayte Young and this is Earth Eats.

MARCIA CHATELAIN: If we have a conversation about healthy foods and they don't involve conversations about capitalism then I'm just not interested in them anymore.

KAYTE YOUNG: This week on our show a conversation with Marcia Chatelain about her research on the historic role of McDonald's franchising in the black community. We join a holiday cookie baking workshop at a food pantry, plus Jackie Bea Howard unrolls the cabbage roll for a winter weeknight meal plan. All of that and more coming up in the next hour here on Earth Eats so stay with us.

(Music)

RENEE REED: Earth Eats comes is produced from the campus of Indiana University in Bloomington Indiana. We wish to acknowledge and honor the indigenous communities native to this region and recognize that Indiana University Bloomington is built on indigenous homelands and resources. We recognize the Miami, Delaware, Potawatomi, and Shawnee people as past, present, and future caretakers of this land.

(Jaunty music)

KAYTE YOUNG: I'm Kayte Young. Thanks for joining us for Earth Eats. Our first stop today is a baking workshop at a local food pantry. This story was recorded last year when groups of kids and families could fill rooms and mix cookie dough and shape cookies together without the fear of spreading a deadly virus. I know we all miss those days and I hope we can soon return to a time when workshops and kids cook sessions can happen in person again. But in the meantime I still like the idea of cookie baking around the holidays and in particular this season.

If you celebrate a winter holiday and you're used to gathering with friends and family, maybe this year you could bake up some extra goodies and send them to a loved one far away. Or you could even drop off a care package on the porch of a friend or family member nearby. Handmade gifts are my favorite gifts. And if you have kids in your household baking can be a nice way to get them involved in gift giving traditions. Making cookies is a great thing to do with kids of all ages. You can keep it simple or go all out, and even the youngest children can probably pour a cup of flour into a bowl or press a cookie cutter into some rolled out dough. Georgia O'Connor and Alissa Weiss are nutrition and youth educators at Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard in Bloomington Indiana.

The "Hub", as the locals call it, is a food pantry and community food resource that offers regular gardening and cooking workshops for children and adults. That is, when there's not a pandemic going on. They've got a spacious teaching kitchen and last year they offered a special pre-holiday cookie baking workshop just for kids. About 10 young bakers and a handful of parents lined the edges of the tall metal tables in the classroom. They had rolling pins, baking sheets, and measuring cups at each station. They taught three different cookie recipes with some of the steps done ahead of time to move things along.

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: [To the children] You’re gonna start by making the modern sugar cookie. To save time we made the dough ahead, but this is a very basic cookie recipe, we'll send it home with you.

So we're gonna do...

KAYTE YOUNG: [Narrating] Alyssa taught the pinwheel recipe. Which included specific skills and techniques.

ALISSA WEISS: [To the children] We're gonna start by measuring our chocolate. We need two ounces of chocolate. So, we're gonna use our scale... and we'll measure out two ounces.

We're gonna use a double boiler, has anyone used a double boiler before?

[Mixed responses from children in the workshop]

ALISSA WEISS: So we're gonna put a pot on top. We're gonna...

KAYTE YOUNG: [NARRATING] They accomplished a lot in those two hours. And by the end of the class each family went home with freshly baked cookies, plus some dough, and instructions for finishing at home.

ALISSA WEISS: [To the children] Alright what are the favorites?

[Mixed responses from children]

CHILDREN IN WORKSHOP: Peanut Butter.

ALISSA WEISS: Peanut Butter?

[Mixed classroom chatter]

ALISSA WEISS: One... Two... Three..

CHILDREN IN WORKSHOP: [All together] Cookies!

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: After the smoke cleared and the interns were finishing the last of the dishes, I sat down with the two instructors.

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: My name is Georgia O’Connor, and I am the youth educator here at Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: What was happening in here today?

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: A lot of kids baking a lot of cookies. Kids with their hands in the dough and kids using their hands to mix up cookie dough, rolling cookie dough, learning new techniques like baking skills such as leveling off, and shifting two different ways, whether you use a shifter or a whisk. The order in which you bake things, so dry ingredients separate then wet ingredients.

KAYTE YOUNG: Is this the first time you've done a cookie workshop with kids?

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: Yes, absolutely, the first time.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, you regularly do cook with kids though, right?

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: Yes, usually we'll do Kids Cook 4:15 - 5 Tuesdays and Thursdays. We usually cook vegetable-based dishes, I do some baking as well but not as often as we do the vegetable dishes.

KAYTE YOUNG: And that's more of a drop-in program, so it's a little bit quicker too?

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: Yes, yes.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, you wouldn't have time for a big baking project?

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: No, we try to keep the recipes for Kids Cook really simple, things that you can duplicate at home quite easily, and that kids could actually participate in. We just use fewer ingredients.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, this was a little bit of an undertaking?

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: Yes it was but it was fun, and I would do it again in a heartbeat.

KAYTE YOUNG: How many cookie recipes did you make today?

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: We made three. We made modern sugar cookies, and peanut butter cookies, and then our last was a Chicago pinwheel cookie.

KAYTE YOUNG: Can you tell me anything about the peanut butter cookie recipe?

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: That peanut butter recipe has been around for a long time. I was about 21 years old and I found it on the back of a domino's sugar box. Wasn't much of a cook then. But I loved that recipe, it was chewy and but crisp at the same time, and so it's one of my favorites. And it calls for like a cup of peanut butter which makes it even better.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, you've stuck with that all this time?

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: Stuck with it, haven't changed a bit. Just doubled the batch is all I do, double the recipe.

KAYTE YOUNG: Why do you think cookies are a good thing to do with kids? Or either of you can answer that.

ALISSA WEISS: I love cookies they're hands on, there's a lot of technique involved in them, they're really fun and easy to do with kids. They bake quickly, and they're perfect for gift giving any time of year, and they're great.

KAYTE YOUNG: Could you say your full name?

ALISSA WEISS: Yes, Alyssa Weiss. I am the education coordinator here at Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard.

KAYTE YOUNG: I’m wondering about the pinwheel recipe, is this something that comes from you? Is this...?

ALISSA WEISS: Sure, yeah. I'm from Chicago, and there was an old cookie manufacturing company called Maurice LeNelle. One of their cookies that they would make that was classic, was this chocolate and vanilla pinwheel cookie with these red sprinkles around the outside. They were the kind of cookies that you get in the tin with the shortbread cookie with the little cherry in the middle. And they closed down a few years ago, and so the bakery I used to work at... kinda brought them back, and it reminds me of Chicago.

KAYTE YOUNG: And so, there's this specific color of sprinkles on the outside.

ALISSA WEISS: Yes, classic red-pink color.

KAYTE YOUNG: Interesting. What is your vision or your goal for what you have in mind when you do a workshop like this with kids?

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: Well, typically our cooking class with kids are only 45 minutes. And so, you can't do a lot in 45 minutes with kids. So, one of the reasons was a longer session to do something that would be... like we've done a pasta workshop for the kids, and that would take a lot longer than 45 minutes. So that was one of the reasons.

We also thought that parents might stick around a little bit more, and they have, they've stuck around and started helping their kids do the cooking as well. And so that makes it kinda fun to have a family orientated project so.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay so, what if somebody says "Well, why are you teaching kids how to make these sweets with sugar in them? And this isn't very healthy... and I just feel like you should be teaching them how to cook with vegetables."?

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: We wanna use fresh ingredients instead of store-bought cookies, that homemade cookies taste so much better, they're fresher, they don't have all the preservatives. And I don't think I've bought a store-bought cookie in several years and part of it is just because I think they taste better and they're better for you. They're just great.

KAYTE YOUNG: And so, all of the cooking lessons that happen here, they're not just focused on super healthy eating... some of it is just about cooking?

ALISSA WEISS: Yeah it’s about cooking and coming together and building community and using our hands, and tasting, and kind of associating conversation and community with eating, and whole foods.

KAYTE YOUNG: Do you find it challenging to work with large groups of kids like this when you're trying to get everybody to focus on a project, it’s the end of the day, they've been in school all day... like, how is that for you?

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: It's bittersweet. I mean it can get chaotic... and you can... in your mind you can be like "Oh whoa, what are we doing here?"

But then you realize this is... kids are enjoying it, they're having a good time, and this is kids having a good time. They are chaotic when they're together in community, so I love it.

KAYTE YOUNG: How do you feel about working with a group of kids?

ALISSA WEISS: Same. I think that it can be hectic, but also very fun, and I also think to add to what Georgia said, that... Do I really think that these kids will be able to go home and cook a recipe from start to finish? No, but I think it’s also about building incremental skills, and exposure to it, and the experience of doing the thing and having fun while doing it, and that is going to create a desire to continue to bake and cook, even if it's not an automatic "I've learned a thing, and now I can go do it". It'll be built into their childhood experience of cooking and baking.

KAYTE YOUNG: The other thing that I was thinking about that so many things that I've been to around the holidays, where there's like a craft, or there's a cookie baking, and you're gonna miss all these workshops and you go in and it's usually like store-bought cookie and you decorate it with store-bought icing.

ALISSA WEISS: And sprinkles maybe.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah, yeah, and that's your cookie baking. And so just to have this chance to do not just one, but three recipes from scratch, all the ingredients, that's kinda a rare thing. Kids don't usually get that kind of experience.

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: It's true. It’s fun to build in these other skills that kids have at varying levels and have the kids work together too. Just always great to see an older kid working with the younger kids and learning about measurements and learning about all the other sciences associated with baking.

KAYTE YOUNG: What are some other workshops that you have coming up?

GEORGIA O’CONNOR: Let's see, we have a pie workshop, in January we're gonna do some winter stew workshops. We've done tortillas, popcorn, all sorts of stuff.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: That was Georgia O'Connor and Alissa Weiss of Mother Hubbard’s' Cupboard. You’ll find all three of these cookie recipes, the modern sugar, the peanut butter, and the Chicago pinwheel on the Earth Eats website, Earth Eats dot org. You can also find links to connect with Mother Hubbard's to learn more about what they're up to. That's Earth Eats dot org. After a short break we have a conversation with a scholar about the surprising role McDonald's franchises played in the black community, so stay with us.

(Jaunty music)

(Music)

Did you know that Earth Eats has a YouTube channel? Well we do. And my colleague Peyton Conoblow has been making some fun recipe videos of me cooking in my kitchen. I've made hand pies, carrot ginger soup, shortbread cookies and more. You might even catch a glimpse of one of my cats. Just search for Earth Eats on YouTube, you'll find us.

(Music)

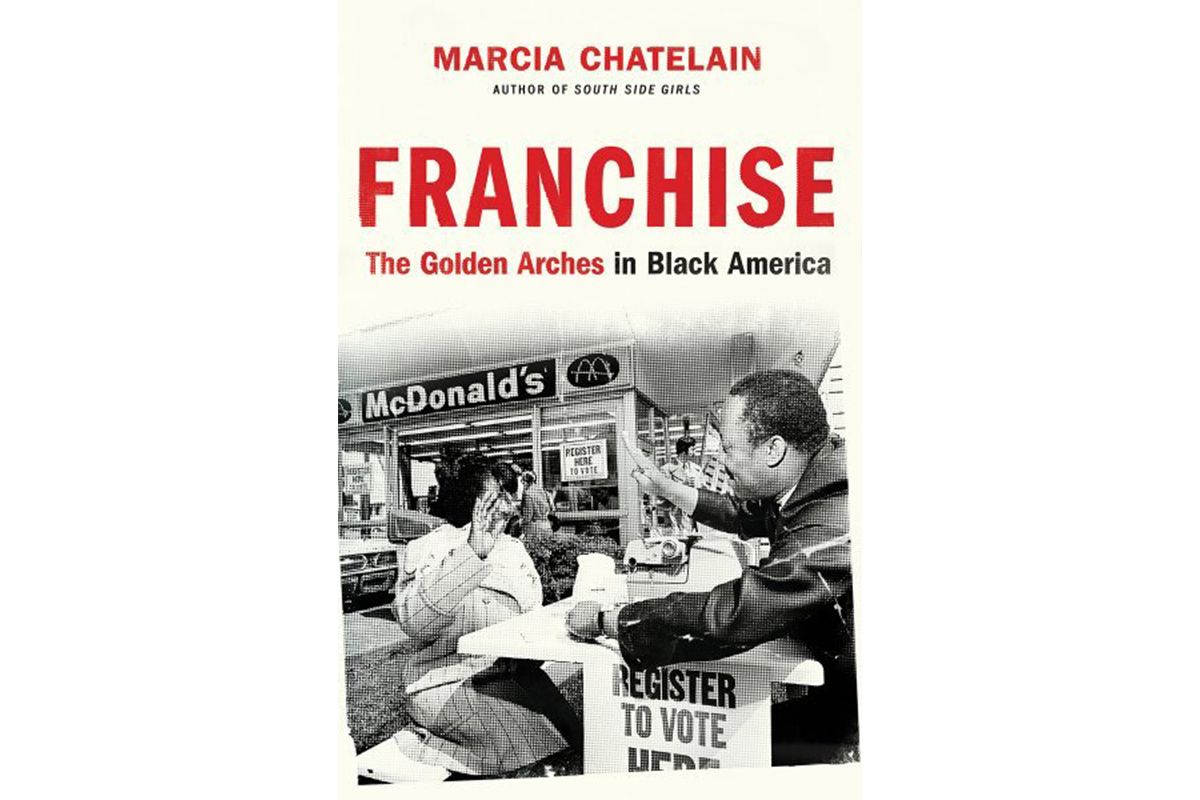

Kayte Young here, this is Earth Eats. For those involved in the Good Food, Real Food and Local Food movements, it's easy to write off fast food, either because it's not good for you, not good for the environment, or because the industry underpays its workers, or maybe it's just not classy enough. But through the second half of the 20th century, African American communities and civil rights organizations saw fast food franchising as a way to bring jobs and money into black communities. It's hard to imagine today that a McDonald's franchise could ever be seen as an engine of black socialism. But Marcia Chatelain, associate professor of History and African American Studies at Georgetown University reminds us that African American communities continue to be constrained and fast food has been one way to make thing works. Dr. Chatelain's first book is called South Side Girls: Growing Up in the Great Migration. And her book Franchise: the Golden Arches in Black America was released in January of 2020. Producer Alex Chambers spoke with her via skype in 2018 before the book was complete.

ALEX CHAMBERS: Your first book was about Chicago into the great migration through the lens of black girls, was there some sort of progression that took you from that to this?

MARCIA CHATELAIN: The kind of bridge I often talk about in terms of my two projects is that after I finished in graduate school and I was traveling between Chicago and Oklahoma City where I first started teaching and then Washington D.C., I would spend a lot of time in my hometown of Chicago. And I always thought it was really fascinating the number of cultural institutions or various activities that I encountered that were underwritten by the local chapter of the National Black McDonald's Operator Association. And I remember in high school the first time I ever read anything about the great migration was part of a history quiz bowl TV show that I was on through my school. And I remember that it was the McDonald's Operators that had paid for the prizes for the competition.

And so it always was this kind of issue in the back of my head in terms of what does it mean for an organization of black franchise operators to not only have kind of so many footprints in a city, but what does it mean for the relationship between communities of color and fast food when they're these franchise orders who are kind of like local heroes or ambassadors, or well-known entities.

ALEX CHAMBERS: I never thought about the fact that the rise of fast food happened right at the same time as the civil rights movement was sort of taking off.

MARCIA CHATELAIN: Right so one of the things I talk about in the book, the first chapter looks at doing a critical race history of fast food and thinking about fast food and the housing market as being very similar. Where there's some of the politics of redlining, there's the federal infrastructure that's allowing a lot of whites who are either leaving the military and using the G.I. bill for business loans or are entering franchising and they're able to be successful.

So franchising kind of grows up in the suburbs and becomes very popular in terms of highway transportation. And all of these structures are so bound by racial constructs of where funding is allocated and where it's not, who has access to houses in the suburbs and cars to drive along the interstates. And then there's this massive shift in the 1960's after 1968 where there are all these uprising after the assassination of Martin Luther King, they're various hot summers. And one of the most consistent refrains or rather responses to uprisings is that poor communities need their own businesses, African Americans really should buy into some of the black capitalism rhetoric that reemerges in this time, and this is going to be the way forward - business. And the business that is kind of ready to pounce is the franchise industry.

When gas prices started to soar and when more and more suburban families were being discerning about how they spent money or whether they want to fill up the car and expend gas to go to a fast-food restaurant, the fast-food industry really saw the inner city as the place to grow. Because it was a larger consumer base that walked to stores and they also knew that putting in black franchise owners would ingratiate them to the community. And one of the things that I think is really important to note when we are talking about these things is that I don't think anyone at that moment could anticipate the size and the consequences of the fast-food industry when they're trying to bring it into communities in the 1960's and 70's. But by the 1980's it becomes very clear that there are some complicated consequences as a result of this this, but this relationship at that point 20 years old. And so you have this kind of brokering between major civil rights organizations, federal subsidies, and then a fast-food industry that is just trying to gain as much ground as possible.

ALEX CHAMBERS: Can you talk about those consequences that were unforeseen that were really are starting to become clear more, you're saying in the 80's?

MARCIA CHATELAIN: Yeah so I think, it's interesting when I'm looking at the early conversations about fast food, some of the critiques of the mainstream fast-food industries, that okay, we really need to have our own black owned franchises. And so there's these attempts to create these companies that are considered authentically black franchises. And they're not able to compete with the wealth and the size of some of these other major ones like your McDonald's, your Kentucky Fried Chicken, your Burger King.

But initially the critique or the resistance to fast food was will this really provide all of the things that it's promising our community in terms of wealth and investment opportunities. And if it's not then we have to build our own fast food. But there wasn't a real kind of concern about it. This idea of a McJob that is low wage, you don't have the right to organize, that it's really physically taxing, that doesn't kind of enter the conversation again until the 80's. And so the critiques that we have today of the fast-food industry they are slow to development. And I think part of the reasons why those critiques aren't leveraged is because people actually think it's not a bad idea. That it could actually be a legitimate source of economic development and renewal because the industry in many ways was still growing as well.

ALEX CHAMBERS: So I'm curious was there a complicated conversation going on around well okay we've got these McDonalds available to us as a way of sparking the economic engine of the community. But were... it's still, it's a franchise. It's owned by a corporation.

MARCIA CHATELAIN: So in the early days of franchising, the post 1954 franchising moment that characterizes a lot of McDonald's growth and its leadership underlay crop, you knew who your franchise owner was because they were actually required to work in the store. So there is way that there is a real kind of personalization of the experience of going to a McDonald's or going to a Burger King or going to a Taco Bell that fades as the industry goes. But initially people actually, they didn't leverage those kinds of critiques about kind of corporate power because there were many ways in which a franchise could still feel very familiar and connected to the community, if that makes sense. Right?

Like there are some questions about is our money going out of or community but then there was also this sense that if we go to a black owned McDonald's we're still able to support our community in some ways because a large part of the culture of franchising in local communities in these early days was about philanthropy and a lot of being very present - donating little league uniforms and doing the scholarships. And the African American franchise owners were particularly attuned to their kind of sense of responsibility and how people in the community would view them in terms of the resources that they could bring. So some of this corporate critique emerges but not in kind of the robust ways that you would think in light of some of the other critiques that are being made about capitalism and systems.

There's this antidote in my book about how in April of 1969 Ralph Albernalph who takes over Martin Luther King at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference he goes on kind of a national tour to commemorate the first anniversary of King's death. And he stops a few weeks before his tour, he gives this speech, and he says, "We don't need black capitalism we need black socialism."

And everyone's like, "What's going on here?" and so shortly after he gives his speech he shows up at this McDonald's from Chicago and he picks up a check from a black franchise owner. And we could say that that act is like rife with all sorts of contradictions and questions, but I think in that particular world there is a way that the economic possibilities of African Americans are so constrained that they have to kind of fit together to get some very basic needs met. So there's no tension in the fact that Abernathy's calling for socialism and then this organization is very excited about franchise possibilities. And so I think that I write about critiques, but a lot of the critiques are about the extent to which McDonald's particularly, because it's the first one that's doing what they call Minority Franchising, the critique is to the extent that they're going to be a citizen, not even like a question about their citizenship in inner-city America.

ALEX CHAMBERS: What do you mean by the critique is that they're going to be a citizen, that it's about how involved the McDonald's going to be in the community?

MARCIA CHATELAIN: Yes. Not if they should be here, it's like "Well how are you going to fit yourself into the things that this community needs and be part of it?" There's another anecdote about Portland McDonald's. Portland Oregon and the local black panther party is accused of bombing them. And one of the reasons that they are allegedly a target is because they won't donate to the breakfast program, and they won't a member of the community in a sense that like this is what you're supposed to do. If you're going to be here and you're going to profit from us there's got to be some exchange. A lot of the strategy that the fast-food industry has to figure out how much do you concede to these demands? How much do you give into these boycotts because they know that they're going to grow, and they know that the inner city is incredibly profitable, and this is a market they want to be in, but they also are very concerned about setting precedent. And so there's these different situations in which these protests, these boycotts of their stores emerge, and the boycotts are about the terms in which they are going to engage the community. Rarely are the protests about getting them actually out of the community.

ALEX CHAMBERS: Right, right. And to a certain degree those protests do make a difference. Right? I mean it seems like there is an effort by McDonald's to start to invest at a certain point in black ownership.

MARCIA CHATELAIN: Yes, so I mean that's the thing. It's kind of the question of what's the goal? If the goal is more franchise owners, yeah you can get more franchise owners. If the goal is to make sure that the franchisee is contributing, absolutely you can get that. I think that a lot of McDonald's success is predicated on this idea of knowing kind of when to get involved and when to step back and let franchise owners take the temperature of communities and figure out their relationships. But a lot of the philanthropy that is associated with McDonald's, the Ronald McDonald houses and all of these different efforts, a lot of these are done by franchise owners and not necessarily the corporation, and there's a reason for that. I think they learn very quickly that franchising works because basically someone else carries the water or takes on all the liability of your company for you.

And part of what I chronicle in the book it that in the 60's and 70's there are "liabilities" of doing business in the inner city. There are the demands of the community, there're the expectations, and there's also some real structural issues in terms of the higher cost of doing businesses in communities that are poorer. And so all of those like issues they're on the shoulder of the franchisee.

And so a lot of what I talk about is this way that even within a system that allows for some African Americans to become wildly wealthy and to have a lot of influence and power, there's still these questions about equity and fairness even within this system because African Americans are ultimately constrained, whether they're constrained in terms of their consumer choices or their constrained when they're doing businesses, these are the constraints that everyone is trying to negotiate and maximize. And I think that if there's a takeaway from my research it's that, what do people do with constrained choices? They make it work.

KAYTE YOUNG: We've been listening to Alex Chambers interviewing Marcia Chatelain. After a quick break we'll hear about her own relationship with fast food and her thoughts on the fight for fifteen.

(Music)

(Music)

KAYTE YOUNG: Marcia Chatelain is an associate professor of history and African American studies at Georgetown University. Let's return to Alex Chamber's interview with Dr. Chatelain.

ALEX CHAMBERS: Did working on this change your own relationship to fast food?

MARCIA CHATELAIN: Yeah so I grew up eating tons of fast food. And it's that kind of thing that's so interesting, I don't eat as much of it now because I'm just older and my digestive systems don't work like they used to. But I will never say that I'm an anti-fast-food person. I have concerns about some of the health consequences and I have concerns about the working conditions. But I also, I think increasingly just more sympathetic to the fact that the choices that people have are the choices they have. And that's fine. And I think I was maybe a little bit more compelled by some of the kind of conversations in the healthy food movement, but if we have a conversation about healthy foods and they don't involve conversations about capitalism then I'm just not interested in them anymore. And I think it's kind of changed the ways that I think about how we solve problems around health and nutrition and it was important for me to write a book about the fast food industry that wasn't about food, but about all of the other things that happens.

ALEX CHAMBERS: So did this lead you to any new thoughts about sort of current issues like the fight for fifteen, anything like that?

MARCIA CHATELAIN: I think that in terms of labor and thinking about the concentration of fast food in certain communities and what job means in some communities and what a job means in others. It just makes me think about all of the things, all of the arguments, and all of the affective work of fast food writing itself within a civil rights context, and how that can be a very effective tool in resisting the demands of workers.

I think about that a lot. Like I was talking to a franchise owner, and I visited one of his restaurants and his manager says to me, "I'm one of the few people that's gonna employ someone with a criminal record. And I give people a second chance." And people saying like, "This is my ministry."

We can write that off and say okay, this person is just saying this, whatever. But I think that some people really do mean this, and some people really do see the jobs they provide as doing something really powerful. I think the problem is, is that for people who are in that orientation we have to help them understand what justice really looks like. And so I think, sometimes I think about, I mean it's this thing I often say to my students, we always think that advertising works on everyone but us because we're smarter than the advertising. But when we think about how this industry has created wealth that then helps pay for historically black colleges and universities to have scholarships and then provides opportunities for sports, and then says, "If you just keep on working at this industry maybe one day you'll make it like I will."

Like even in my most cynical moments I get how people are really moved by that. And the question is for those of us who have a different vision of justice and opportunity, what are we gonna provide that is as compelling and as affective so that people will believe us when we say that another world is possible.

KAYTE YOUNG: That was producer Alex Chambers interviewing Marcia Chatelain, associate professor of history and African American studies at Georgetown University. Her book, Franchise: the Golden Arches in Black America, was released earlier this year.

(Music)

(Music)

The coronavirus pandemic is just the latest in a string of newly discovered highly infectious diseases. Many of them start in animals and can have just as big of an impact on our lives even if they don't jump to humans. Brian Grimmett reports for Harvest Public Media on how the agriculture industry is using lessons learned from COVID-19 to prepare.

BRIAN GRIMMETT: Emerging infectious diseases like the coronavirus don't just threaten humans, they're also a major threat to the chickens, pigs, and cattle that become food for billions of people. If a foreign animal disease such as food and mouth, African swine fever, or one that we've not even discovered yet made it to the U.S. it would cost the U.S. economy billions if not trillions of dollars.

JACK SHERE: We have a lot of movement of animals, we have very integrated systems. And disease can spread very easily.

BRIAN GRIMMETT: That's Jack Shere, he's the associate administrator for Emergency Program Planning, Response, and Security at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. He says there's a lot his agency can learn from the U.S. response to the coronavirus, mainly that an emergency response to an infectious disease requires a lot of equipment and scientists to be in place before it happens.

JACK SHERE: No one likes to pay for all the response capabilities when nothing happens, but then when it happens people look at each other and say, "Why weren't we better prepared?"

BRIAN GRIMMETT: But the coronavirus isn't the first wakeup call for the agency. In 2015 a highly infectious strain of avian influenza wreaked havoc on the chicken and turkey industry in the upper Midwest. In total more than 50 million birds died from or had to be euthanized because of the disease. It also resulted in trade restrictions that caused more than a billion dollars in lost export revenue.

JACK SHERE: They are devastating diseases, that's why we want to keep them out. And that's our goal.

BRIAN GRIMMETT: A big part of that strategy involves the Department of Homeland Security which supports several important research laboratories such as Plum Island Animal Disease Center in New York State. Bob Burns leads one of Homeland Security's Science & Technology divisions. He says people shouldn't be surprised if a foreign animal disease shows up. In fact they should be surprised more haven't already.

BOB BURNS: It's always a threat, it's the potential for emergent threats, emergent disease, future disease is real. And we need to pay attention to that.

BRIAN GRIMMETT: He says just as we've seen with the coronavirus outbreak, a key to stopping a foreign animal disease will be quickly identifying what it is and where it's been. But you can't have a diagnostic test if you're not already studying or aware of the disease. That's why DHS is currently constructing a 1.2-billion-dollar facility in Manhattan Kansas known as the National Bio and Agro Defense Facility. When up and running in 2022 it will be one of only 4 labs in the world that can work with large live animals and highly infectious diseases for which there aren't vaccines.

As hard as the USDA and Homeland Security work to prevent a disease from reaching the United States the first to recognize an actual outbreak will likely be the farmers, ranchers and feedlot operators that are in constant contact with the thousands of animals every day.

(Cow mooing)

Brandon Depenbusch is the vice president of cattle operations for Innovative Livestock Services. It operates 8 feedlots in Kansas and Nebraska. At his feedlot in Great Bend Kansas he says caregivers perform a health check on every pen at least once a day.

BRANDON DEPENBUSCH: So that'll mean one caregiver gets in each pen and will go around and make sure we got every animal up, walk them around, and look at them visually and make sure that they don't have any signs or symptoms of any kind of disease. They'll look for same thing we look for in our kids, runny nose, a depressed look, an appetite for stuff.

BRIAN GRIMMETT: Depenbusch says he thinks about the consequences of a foreign animal disease outbreak almost every day. It's why he's participating in the secure beef supply program, it's a coordinated effort between the USDA and a few states including Colorado and Kansas to help train and prepare cattle, pork, and poultry operations on disease response plans.

JUSTIN SMITH: Yes it's a plan sitting on the shelf, we want to make sure that it stays on the shelf. But at the same time when it's time to do, they can open the book and say, "Yeah, I know what I'm gonna do."

BRIAN GRIMMETT: That's Kansas Animal Health Commissioner Justin Smith. He says in the case of an outbreak, the department's plan is aggressive. That means immediately stopping all movement of animals, tracing where infected animals have been, an setting up barriers between operations to prevent disease from spreading. And that last one is a real challenge. Depenbusch says that any one of his feed yards they'll have as many as 75 delivery trucks enter the property every day. Each one potentially carrying a disease from another lot.

BRANDON DEPENBUSCH: At the entry gate we would have a checkpoint and depending on the scenario of there'd be a wash, a cleaning and a disinfectant. So we would wash the wheels, the wheel carriage, undercarriage of any debris and then disinfect it.

BRIAN GRIMMETT: That'll slow down the feedlots and require a lot more workers. He says that's not sustainable long term but it's a lot cheaper than the alternative which is getting a call from the state Department of Agriculture telling you to euthanize 30,000 head of cattle.

BRANDON DEPENBUSCH: That might be one of the things that's come out of COVID-19 is maybe now producers are saying "Hm, you know what. Maybe I outta give that a little more thought on our operations. What would happen if we had that?"

BRIAN GRIMMETT: Depenbusch is also involved in an effort to create automated cattle tracking system known as U.S. Cattle Trace which Kansas piloted. But he says some producers are worried about government intrusion into their data which is only shared during the emergency.

BRANDON DEPENBUSCH: Cannot talk about enhanced biosecurity plans without a least mentioning animal identification, because one without the other is not good.

BRIAN GRIMMETT: Plus in 2008 Kansas started doing large scale foreign animal disease disaster drills, multi-day exercises involving producers and several state agencies. Scarlett Hagins is the vice president of communications for the Kanas Livestock Association. She says the drills have been a huge success. They've also helped strengthen relationships between producers and the state which will be necessary if serious measures need to be taken to stop a disease. If you're looking for a parallel, think about the debate over the mask mandate.

SCARLETT HAGINS: I think the trust is there and that if something came up and this is kind of this what would need to be done, I think that our producers would do the best they could to accommodate that.

BRIAN GRIMMETT: Kansas is unique, it's the only state currently doing drills on this scale and frequency. Smith, the Kansas Animal Health Commissioner, says it's not the AG departments in other states aren't aware or concerned, it's that lawmakers and governors haven't made it a priority yet, and that worries him.

JUSTIN SMITH: There's really not a whole lot sovereign about those state lines, they're pretty porous, and we have a lot of movement that happens across state lines, and we have a lot of businesses that happen across the state line.

BRIAN GRIMMETT: The plan to respond to the next foreign animal disease outbreak shares a lot in common with the recommended response to COVID-19. to stop either you have to have systems in place to test and trace, you have to isolate the infected from the healthy, and in the end the heaviest burden falls to state and local agencies, most of which aren't nearly as prepared as they should be. For Harvest Public Media I'm Brian Grimmett.

KAYTE YOUNG: Harvest Public Media is a reporting collective covering food and farming in the heartland. Find more at Harvest Public Media dot org.

(Music)

(Music)

I'm Kayte Young, thanks for joining us for Earth Eats. Next up we have a recipe from Jackie Bea Howard. She has a history of professional cooking and she's been on the show before. You might recall her amazing savory persimmon recipes and her meal prepping tips. Today she's sharing a great wintertime meal based on the traditional cabbage roll. In Jackie's version she does away with the fussy rolling up of the filling in a cabbage leaf and tops it with a flavorful romesco sauce. It's sort of an unrolled cabbage roll. Jackie also schools us on the three stages of a good bite. Let's listen.

JACKIE BEA HOWARD: One head of organic cabbage, and I'm gonna give it a big chunky dice. Since we're not taking the leaves off and rolling them, I still want that sort of like big leafy feel to it so I'm gonna leave them in big chunks in my sauté. I've quartered the cabbage and then halved each of those quarters and cutting them into one-inch chunks.

(Sound of cabbage being chopped)

I've got my pan hot, it's ready to go, and I'm putting in about 2 tablespoons of olive oil. Mom would use butter for this, my mom would use butter for anytime we're having cabbage. You can do that too, but I'm gonna use olive oil.

What's great about cabbage is it's really economical, a little goes a long way, and a whole head of cabbage is gonna make a meal for four people easily.

While this is going I've got some almonds toasting in the oven for the romesco sauce. That romesco, if you're not familiar, it's a roasted red pepper sauce with almonds. And for me the two ingredients to make a fantastic romesco sauce is lots of smoked paprika, and a good sherry vinegar. Sherry vinegar can be hard to find sometimes, if you really have to sub it you can do a sherry cooking wine and red wine vinegar, but I highly recommend seeking out that sherry vinegar and then just have it at home so that you can do this whenever the mood strikes.

(Sound of a pan sizzling)

So I put in a pound of ground turkey on that olive oil. I'm doing some oil because the turkey's lean, and I want to make sure that it pulls out, it adds a little bit of fat to that turkey to pull out some flavor and get a nice base for adding when I want to add the cabbage to it as well.

Doing about a teaspoon of salt and about a teaspoon of black pepper, just right on my turkey to season it. I'm not going to do much to season it because I'm going to make the romesco sauce and I want that to be the main seasoning component. So for the turkey and cabbage itself, it's really just gonna be salt and pepper.

Right, so while that's cooking I'm gonna start on the romesco sauce. So I have a jar of roasted red peppers, they're in olive oil, it's a 12-ounce jar. I'm gonna use all 12 ounces of this. I'm gonna drain the liquid from it and just use the peppers themselves. These peppers have a few garlic cloves them. I'm gonna leave those as well as, I've retained about 2 tablespoons of the olive oil from the jar. And I'm adding two fresh garlic cloves.

(Sound of food processor whirring)

Alright so I've blended that up. I love how beautiful roasted red peppers puree together, it's just so bright and exciting. I love it so much.

And then I am gonna take some flat leaf parsley. You wanna use fresh if you can, if you can't I wouldn't use a dried parsley in this, I would just do like a dried oregano. There are ways to be traditional about it and then there are ways that utilize what you have. And that's the most efficient if you only are ever doing a recipe because you have all of the ingredients and that's the only time you're gonna cook, then you're so rarely gonna cook and it becomes such a stressful thing. But if you give yourself the freedom to play around and use what's available then you'll find yourself cooking often because you can see far more possibility with what you have.

Alright so while I was getting the sauce prepped, my ground turkey is about cooked through so I'm gonna go ahead and throw the cabbage in here as well while I finish the sauce. Now I'm doing it in a big Dutch oven so I'm gonna get about half of this cabbage put in at one time and then we'll add the other half. I actually like that texture difference; some will have a little bit more bite to it than others and I prefer that. I'm adding another half a teaspoon of salt and pepper to our cabbage. I'm gonna let that sit and sauté a little bit while I finish the sauce.

I've got the roasted red peppers, the garlic, the herbs. I'm gonna start with about a quarter of a cup of the almonds, it's gonna be really loud.

(Sound of almonds tumbling into a food processor, then sound of processor whirring)

I'm gonna add another handful of nuts, a tablespoon of smoked paprika and I'm gonna go ahead and put in a couple of teaspoons of sherry vinegar, probably gonna end up at about a quarter of a cup in terms of the flavor that I like from it. It's gonna be loud again.

(Food processor whirring)

The cabbage and turkey is starting to cook down a little bit. I'm gonna go ahead and add the other half of my head of cabbage to this. Traditionally a cabbage roll is just sort of a basic tomato sauce, so we're playing around with that with the romesco. Roasted red pepper and sherry vinegar are gonna be really good with the cabbage, so it's a nice, it's a fun play, and I think also that the almonds in the sauce are gonna add a really nice texture to it as well.

So I'm tasting, you can see that the sauce is much thicker after our second round but still not pasty. So good. You wanna taste it?

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes. Yeah that's really good. I think it needs salt. Yeah, but maybe not too much.

JACKIE BEA HOWARD: Alright. And we'll see how this goes once it melts with my turkey and cabbage. So I have put in more sherry. I also think that the smoked paprika is at a really nice level right now and we'll see how that might need to be adjusted after it gets cooked in with the cabbage.

So I'm putting this right into my pot with my cabbage and the ground turkey. With most good things the longer they sit the better they taste, the flavors meld together. But I'm gonna give this a taste now and see if there's any sort of initial adjustments I wanna make to the flavor.

So I think that it needs some more sherry vinegar and a little bit more salt. If I want I may add more oregano as well. Now this is very much a down home sort of meal, it's not the prettiest thing you've ever eaten. You could pretty it up. Easily this could be deconstructed if you wanted to be fancy about it, or you know if you wanted to be really fancy roll it. (Laughs).

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: It was time to tasted the unrolled cabbage rolls with the romesco sauce added to the pan.

[TO JACKIE] Yeah that additional sherry vinegar really brought out the other flavors.

JACKIE BEA HOWARD: The green vegetable in particular needs some sort of, it's so hardy and deep and earthy in flavor that it needs that brightness, it needs that acidity to brighten that up. In the middle of the bite it really falls flat, and it doesn’t, it's not bland, but it doesn't taste like... you don't feel any sort of like pop out of it.

KAYTE YOUNG: It doesn't excite?

JACKIE BEA HOWARD: It doesn't... that's great! Yes! It doesn't excite. And if it's not that excite then it needs acid. That's a great way to put that, yes.

KAYTE YOUNG: How would I know that it wasn't salt that it needed?

JACKIE BEA HOWARD: When you're tasting something there are three stages to it. The first one can I taste this when I put it into my mouth can I taste it? Do I have some sort of initial flavor to it? If it doesn't, it needs salt.

You want it to be flavorful, exciting, then deep and warm. Those are the three steps of what a good bite should taste like, what a good dish should taste like. So just put a little bit of thought behind it, I promise you will find those things too. You just have to identify it for yourself.

KAYTE YOUNG: And the paprika and the herbs are offering that warmth.

JACKIE BEA HOWARD: Correct, as it sits the nuttiness of the almonds is gonna contribute to that as well. The roasted red peppers are adding to the acid, the roastyness of them adds to the depth. So it's a fun... tasting is really fun.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes, tasting is fun. Especially when you get to taste what Jackie Bea Howard is making. That romesco sauce hits all the notes in all three stages of the bite. She makes it easy for you to try it too, find this recipe at Earth Eats dot org.

(Music)

(Earth Eats production support music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

RENEE REED: Get freshest the food news each week, subscribe to the Earth Eats Digest. It's a weekly note packed with food notes and recipes, right in your inbox. Go to Earth Eats dot org to sign up. The Earth Eats team includes Eobon Binder, Mark Chilla, Abraham Hill, Josephine McRobbie, the IU Food Institute, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week Marica Chatelain, Alex Chambers, Jackie Bea Howard, Georgia O'Connor, Elisa Weiss and everyone at the Hub.

RENEE REED: Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from the artist at Universal Productions Music. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey.