KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana, this is Earth Eats and I'm your host, Kayte Young.

AUSTIN FRERICK: At least 100 years ago, the last robber barons, we got, like, nice libraries out of it. This one, it's, like, "oh what is the family using its money for? To gut public education via charter school networks?" It's, kind of, Machiavellian. It's Machiavellian in a really sad way.

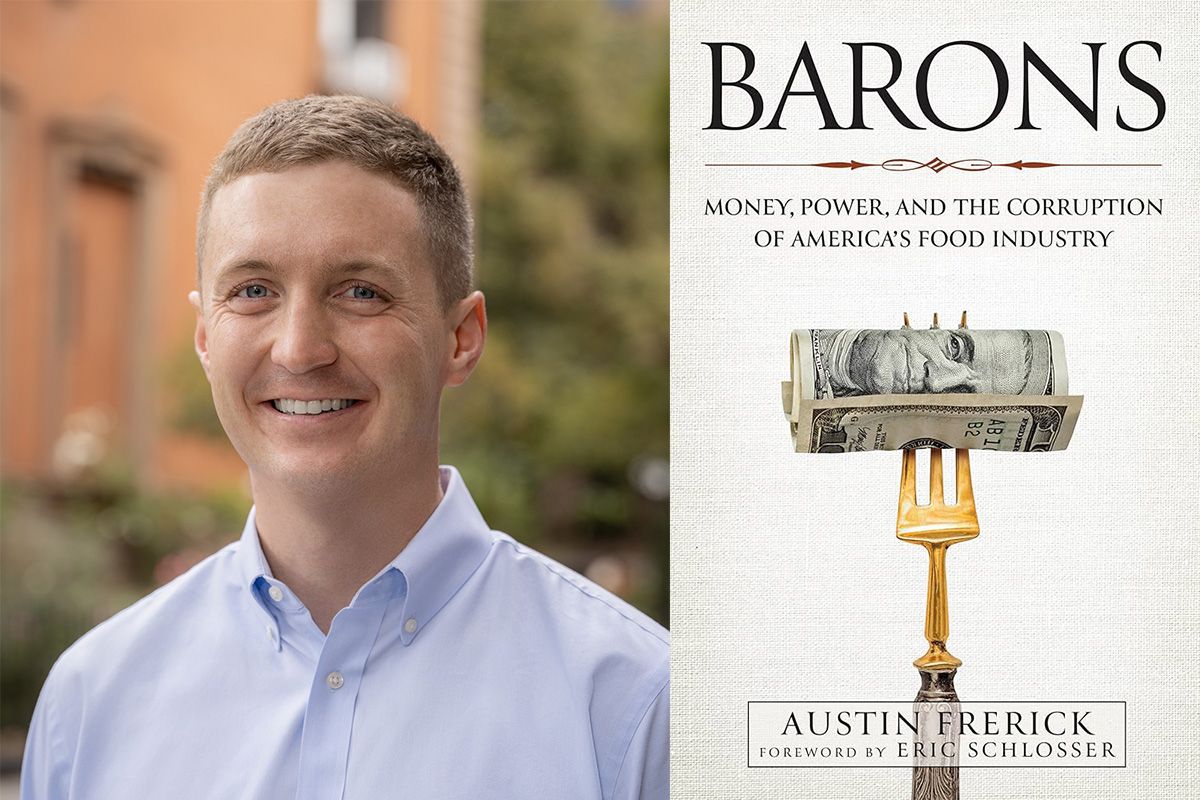

KAYTE YOUNG: This week on the show, I'm talking with Austin Frerick, the author of Barons: Money, Power and the Corruption of America's Food Industry. Frerick uncovers the sometimes shocking facts about seven large companies who play an outsized role in our nation's food system, from Hog Barons to Coffee Barons to Indiana's own Dairy Barons, Fair Oaks Farm. A conversation is just ahead. Stay with us.

KAYTE YOUNG: Thanks for listening to Earth Eats. I'm Kayte Young.

AUSTIN FRERICK: To me you have to understand how power is amassed to deconstruct power. That's honestly half of why intellectually I wrote this book. And the second is greed always goes too far and I purposely use a Robber Baron framework to show people we've been here before.

KAYTE YOUNG: My guest today is Austin Frerick. He has expertise in agriculture and antitrust policy. He's worked at the Open Markets Institute, the US Department of Treasury and the Congressional Research Service before becoming a Fellow at Yale University. His new book is called Barons: Money, Power and the Corruption of America's Food Industry. It's one of those books that exposes some ugly truths about our food system and does so in a way that is clear and informative. His work uncovers corrupt individuals, flawed institutions and poorly designed policy, which I get, it doesn't sound all that pleasant, but we all know that the first step in addressing a problem is to face it. Austin Frerick's book Barons allows us to do just that. Most of us are involved in the food system primarily as consumers and it's important for us to understand from a systems perspective the forces that are shaping the growing and processing of the food we eat and how those forces are affecting our environment, labor conditions, animal welfare as well as the price and the quality of our food. For that reason, I'm excited about this conversation with Austin Frerick about his book. Quick warning: Austin talks pretty fast. We will do our best to keep up.

AUSTIN FRERICK: So, my book is structured around seven different barons in the food system and I really think of each baron as a narrative vehicle to tell bigger structural stories in the food system. One of my barons is Cargill and my Grain Baron and I really use their story to tell the story of the corporate capture of the Farm Bill. What is it? What happened to it? What has it done to us? Another baron of mine is Driscolls and my Berry Baron and I use their story to tell the bigger story of, you know, the offshore in a lot of the produce system in America, but also a lot of the dark undercurrents of the past in the food system are coming back, where a lot of their production models are basically rooted in modern day share cropping.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, that's the basic structure is it focuses on these seven families, seven industries, seven companies and the focus is specifically on the food system. And I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about your own background and what led you to this work and why it is focused on food.

AUSTIN FRERICK: I'm from Iowa, seventh generation Iowan and Iowa is to agriculture what Hollywood is to films. So, you know, it's painted into the background in Iowa and also just I grew up in it. My mom ran a bakery for most of my childhood. My dad's been a beer truck driver and now he's a corn ethanol truck driver. You know, I've detasseled. I've done all that sort of stuff, but then also to me stepping back to it, so much of this book is what happened to Iowa in my lifetime and, kind of, grappling with that, figuring it out where Iowa should be the Italy of North America, yet it's, kind of, the canary in the coal mine for how much this stuff has gone off the rails where it's now one of the most obese states. It's the second highest cancer rate in the country. Just, kind of, everything wrong with the food system you see really play out here.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes, so it seems like a lot of this is personal, like, a lot of the stories that you talk about. That you talk about, like, and this high fructose corn syrup was first manufactured in a plant that down the street from the church my grandparents went to or something. So, I can see that some of this does feel personal to you, that you have watched some of this happen over your lifetime and then also the more you research, you're hearing the history of these places and these industries and what has changed. Could you also tell us a little bit more about the story of your mom's bakery.

AUSTIN FRERICK: My mom's bakery story is in my Coffee Baron chapter. My Coffee Baron is a secret German family, JAB, the Reimans. Most Americans have not heard of them, but they probably had their product sometime in the last month. They entered the American coffee market in 2012 when they first bought Peet's and they went on a massive acquisition spree that would not have been possible just a few decades ago, to the point now where they sell more coffee than Starbucks. They bought Panera, Stumptown, Krispy Kreme, Pret a Manger, Einstein Bagels, Brueggers Bagels, Noahs Bagels, those little carry cups. Just tons of brands. So, I use their story to tell this bigger story of the collapse of these guardrails we had that stopped the consolidation of power. But then at the same time too I wanted to tell the story of my mom's bakery because in this consolidation I want to talk about what we've lost and how much we've lost as value of local, means local places like my mom that maintain culture, that kind of make a place a place and these consolidated markets, and I saw this with my mom. My mom actually closed the bakery and sold it. She went to go work for Starbucks basically, in a Target. And you just, kind of, lose the sense of agency in these companies. They tell you what to do. They don't give you much room to run. And I want to touch on that because I saw how much pride my mom had from her bakery, the sense of community she created.

AUSTIN FRERICK: Whereas my secret German family, well first of all they're headquartered in Luxembourg and that's a tax advantage thing. Their American headquarters is next to the White House, which tells you everything, which I almost found to be a cartoonish detail, but they don't pay for local non-profits. They're not a member of their community. They don't maintain culture and so that's why I really want to touch on that, is it's not just the consolidation story, but it's also just what we've lost in that consolidation.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes. Maybe we could talk a little bit about generally some of the things that we've lost and who is being harmed by this consolidation that's happening and it's so broad. It's workers. A lot of this work is dangerous, it's unhealthy. People are mistreated and exploited and then there's also the environment, air quality, water quality, land and that, of course, impacts everyone and then consumers of food. Whether it's not really having choices or whether it's the quality of the food and the health. Small towns, rural economies are being affected. It just feels like it's really broad reaching.

AUSTIN FRERICK: On the flip-side that's what gives me hope is, first of all, one in ten Americans work in the food... some people, like mom and dad and everyone's just seeing in different ways it's not working. I mean I've got praise from the American conservative from this book. I went on Bloomberg's podcast and they really, I mean business travelers enjoy this book because they go abroad and it's like cliché to say, "I went to Italy, ate better food at a cheaper price and lost weight." Which, let me sit back for a second and just let people know industry will always say this is cheap food. That's just not factually true. When you pull the data per dollar what you spend in the store, Americans spend more money on food than most Western democracies. What about dollar for dollar for Italy? And what that dollar gets in Italy is very different than a dollar here, which we shouldn't be shocked. I mean I would argue the food industry is the most concentrated space in America and concentrated markets gouge. I mean the goal of any corporate executive is monopoly. We're all seeing the harms of that in all these different ways.

AUSTIN FRERICK: And so that, to me, is what gives me hope right now is there really is a bipartisan moment for reform, especially meat packing where when you learn about monopoly growing up, you learn about meat packing and you learn about what Teddy Roosevelt did to break up the trust. And so it's not rocket science. We're not talking about AI here. We're talking about hogs.

KAYTE YOUNG: I did want to go through and just, kind of, name the seven barons and industries.

AUSTIN FRERICK: My first Baron I open my book with is Jeff and Deb Hansen. They own Iowa Select Farms. They're industrial hog farmers. I mean I use their story to tell the story of state capture of Iowa. My second Baron is Cargill, my Grain Baron. My third Baron, as I mentioned earlier, is coffee, JAB. The fourth Baron is Fair Life, Fair Oaks Farms, was created by Sue and Mike McCloskey in North West Indiana. My fifth Baron is Driscolls, my Berry Baron. My sixth baron is JBS, my Slaughtering Baron. And then my final Baron, my king of kings, my Grocery Baron, is Walmart. Walmart's power is just on a scale we'd never seen before in the food system, which is, it's really hard to get your head around. When I started this book, I didn't think of them as a grocery store, even though I've been to Walmart plenty of times, but 60% of their sales is grocery. They sell one in three groceries in America and their market share is the same as the second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth combined. And it's just they're the richest family in America. Some days they're the richest family in the world. It kind of depends. Keep in mind, Jeff Bezos only owns, like, ten percent of Amazon. The Walmart family owns around 50% of the company, so they control it and so it's just wild. They're just at a scale that one else is and we've never really seen before in the history of mankind in the food system.

KAYTE YOUNG: And you're right, we don't usually think of them as being a part of the food system in the same way as we might others. Like, when I think of big groceries, I think of Kroger.

AUSTIN FRERICK: To me, when I think of Walmart, when I started researching them, is I honestly think they're the closest thing we've ever had in America to a Soviet Union style politburo. It's supply and command. They dictate to the food economy. I mean you don't negotiate with Walmart if you're a supplier to Walmart. They tell you the terms and you take it or leave it. My favorite little example of their market power is Walmart has a role as a vendor to Walmart, no more than 30% of your sales can come from Walmart. I honestly didn't understand why at first. I asked around and a grocery person told me it's because they're just like awesome, this is a supply chain risk management strategy. Walmart knows it's such a vulture that if you go over 30% of your sales, you put yourself at the risk of bankruptcy. So, it doesn't want to kill you, but it wants you on life support.

KAYTE YOUNG: So, what do you mean by no more than 30% of your sales? Like, what are you talking about?

AUSTIN FRERICK: Let's say you're Smuckers, which, you know, you're selling peanut butter. No more than 30% of your peanut butter sales can occur out of Walmart. You need to get 70% of your sales somewhere else, because Walmart knows you basically sell Walmart at cost because it's such a vulture. So, you need to go and make that 70% elsewhere, whether it be that local Ma and Pa, that Kroger. It's classic story of monopoly too, is you want to lock in your dominance.

KAYTE YOUNG: Wow. So they're basically saying you can't survive as a company if you sell to everyone, if you sell at this price. So, you have to get it-- It's like their price has to be subsidized by the rest of their business. That's, yes, that's pretty wild.

AUSTIN FRERICK: Run with that logic, though. I mean the amount of subsidies in this empire is insane.

KAYTE YOUNG: In Barons, Austin Frerick talks about how low wages at Walmart obscure a generous hidden government subsidy that the company receives. Many Walmart employees depend on government programs like Medicaid, earn income tax credits for low wage workers, Section 8 for housing and SNAP for food purchases. One congressional report from 2013 found that our taxed dollars subsidies more than $5,000 per Walmart employee per year when you add up all of the government programs the workers need and qualify for because Walmart does not pay them a living wage.

AUSTIN FRERICK: So much government welfare runs through the registers both their employees using SNAP dollars but also their clientèle.

KAYTE YOUNG: I used to work in the food banking, food security sector. I worked for a food pantry and the food bank where we got our food had a relationship with Walmart that was also very restrictive and dictating lots of terms. Yes, I just remember some of the battles that we had around not wanting to take all of this surplus sheet cakes and various bakery items that they were producing because we didn't really want to fill our shelves with that. They're a big hassle to deal with, you know, they're a mess and it just felt like why are we disposing of Walmart's waste? It's like nobody wanted to mess with that relationship because they were connected to these larger systems of food banking and provided a lot of excess food. Yes, it was really problematic.

AUSTIN FRERICK: What Walmart wants to donate to you guys, especially the sheet cake because they get an enhanced tax deduction. You know, instead of just throwing it away, they get some more government welfare on top of it. I mean what really bothered me about Walmart too is just at least 100 years ago the last Robber Barons, we got nice libraries out of it. This one, it's, like, "oh what are the family using its money for?" To gut public education via charter school networks. And the under appreciated thing in the food system is how much food reform groups are financed by the Walton family. And it's hard, I understand. It's really hard to run a non-profit. I mean a lot of it they want people to talk about food assistance, maintain SNAP. I get it, which is fine, but there's a missing power critique there. Well why do people need food assistance if they're working full-time, you know what I mean. There's that disconnect there. It's, kind of, Machiavellian. It's Machiavellian in a really sad way. To me, you have to understand how power is amassed to de-construct power. That's honestly half of why intellectually I wrote this book. And the second is greed always goes too far and I purposely use a Robber Baron framework to show people we've been here before. Like, it's cartoonish that we have a Berry Baron at this point.

KAYTE YOUNG: It truly is cartoonish. And speaking of things that are playful and fun, in his book about Barons and the food system, Austin Frerick devotes a chapter to the couple that runs the agro-tourist destination, Fair Oaks Farm, right here in Indiana. We'll hear about that after a short break. Stay with us.

KAYTE YOUNG: We're back. This is Earth Eats and I'm Kayte Young. My guest today is Austin Frerick, the author of Barons: Money, Power and the Corruption of America's Food Industry, released in 2024 with Island Press. Since Earth Eats is a show based here in Indiana, I want to spend some time talking with Austin about who he calls his Dairy Barons, namely Mike and Sue McCloskey of Fair Oaks Farm. Besides being a mega-farm in North West Indiana, Fair Oaks is also a tourist attraction where visitors can, according to their website, experience a full day, or a whole weekend, of "hands-on education, laugh-out-loud fun and great food".

AUSTIN FRERICK: It's one of the most popular tourist attractions in the State of Indiana. Mike and Sue, there's a delusionalness that's incredible to see. And also I think their rise as Barons actually reflects the state of American media and I'll get to that point in a second. Both their stories are both fascinating and incredibly scary in that neither one comes from a farm family, which is, unless you're born into a farm family at this point, you can't really break into it because of land cost, capital cost, all that stuff. She's from the suburbs of New York. She was an art student and he was her landlord. He's a veterinarian by training. And that's how they met. They started with an industrial dairy operation in California. They moved to New Mexico, which unbeknownst to most Americans, New Mexico does three times more dairy than Vermont at this point. It's pretty awful, pretty cruel to put cows out in that kind of heat in the desert, but they saw the writing on the wall.

AUSTIN FRERICK: I mean the story of their rise as Barons is they were just one step ahead of everyone else. They saw the coming water crisis in the west and up in North West Indiana along the interstate, 20,000 acres of farmland came available for sale, which you don't see that much farmland for sale at once in the Midwest and that was because I learned that this was supposed to be a third airport for the Chicago area. They bought it and they moved their industrial operations there and at this point roughly about 35,000 cows are milked there. Just put that in context for people. I believe that's, like, four million school milk cartons a day, but it's also incredibly toxic, or destructive for the environment because cows defecate a lot. So, the amount of manure produced in that facility, or 35,000, cows is equal to that to the city of Austin Texas in a given day, which is wild to me. I didn't know this until-- when I was driving around there is I've never seen canals around cornfields before in the Midwest so I was, like, what's going on here? This is really weird. It's really flat. I started researching. That used to be an everglades. North West Indiana used to be the Grand Kankakee, if I'm saying that correctly. Everglades of the north. Those everglades were drained and put into roll crop production.

KAYTE YOUNG: When Austin says the Everglades, what he means is that this was a wetland area known as the grand Kankakee Marsh. It was a massive wetland that stretched across northern Indiana and into Illinois. Back in 1838, the Potawatomi people who lived in the marshland were forcibly removed by the Indiana government in a massacre known as the Trail of Death. Then the white settlers drained the wetlands to convert it to farmlands, hence the canals that now outline much of the McCloskey's farmland.

AUSTIN FRERICK: Part of the reason why Mike and Sue moved their dairy operation there was because of Mike's veterinary training, he realized cement is really hard on industrial dairy cows to stand on, so you want to make them sand beds. And so he was able to essentially likely create a sandpit from the everglades to then make sand beds for his industrial dairy cows. Part of what's wild to me is they sold the popular narrative for a long time, how they're environmental stewards. First of all, if they were environmental stewards, you would not do industrial dairy. You would not do dairy production this way, let alone in that area. That's fact number one. But the one that's really wild is there's this dairy program called Checkoffs which this is what this chapter's really built around for me is I really think Checkoffs control the conversation over the American food system. These things go back to the new deal. They were just tiny little things, like, it goes all the way back to Florida where Florida orange juice, people literally checked a box saying, "yes, I will pay a tax into a pot of money to advertise, like, drink more Florida orange juice."

AUSTIN FRERICK: These things really didn't matter up until the 80s and then as the Farm Bill became, what I call the Wall Street Farm Bill, which is it's overproducing a few key things for Wall Street at the expense of all of us. The Checkoffs became, how do we get you to consume more of these oversupplied markets? So, Got Milk is the most famous example of that.

KAYTE YOUNG: Got Milk and I remember one from when I lived in California about summer fruits.

AUSTIN FRERICK: Yes, I mean "Pork. The other white meat". There's all these little ones.

KAYTE YOUNG: Note, the topic of Checkoffs is a big one. Maybe too complicated for us to go way into here. Basically it's a fee that farmers pay for national marketing campaigns for each particular industry, like the examples Austin just mentioned. "Got milk" or "Pork. The other white meat". It's a system that's been in place since the mid 1950s and it's a tax that farmers have to pay. They don't have the choice to not check the box. In his book, Austin Frerick details all of the ways this system is problematic, including the lack of transparency and how the funds are used. They've been used to seed doubt about the dangers of tobacco use, to spread misinformation about climate change or to fund junk science on a number of commodities. And they generally benefit large corporations over smaller family farms. Yet, the small farmers still have to pay into it. The money is often spent promoting the kind of industrial agriculture that drives independent producers out of business.

AUSTIN FRERICK: Here's the thing, Mike didn't like it. So, Mike saw what happened to the Iowa hog farmers in the 90s and realized he needed a branded product. He's not going to go down like them. So, he, when he was down in New Mexico was testing out his own little patent dairy milk, Fair Life.

KAYTE YOUNG: I'm going to interrupt here again to clarify. At this point, dairy prices had dropped significantly and it was difficult to make a living in dairy at any scale. Austin Frerick says this is because of industrialization of the daily system, which he says started in Bakersfield, California where industrial dairy cows are sometimes right next to oil rigs where the operations are taxing the local aquifers. He points out than when you're using undocumented labor, exploiting the environment, mining the resources, you can create an artificially low price, flooding the market, and this drives family farms that are trying to produce pasture dairy, it drives them out of business. And even the industrial dairies are barely getting by and so they keep pushing it, adding more cows, trying to make the numbers work. This is where Mike McCloskey found himself.

AUSTIN FRERICK: So, he realized he needed a branded product. And so basically what Fair Life is, it's twice the price of milk for half the volume as one Coke exec put it. Has a long shelf life, has a really high protein content, young men love it. You go to any gym in America now they love drinking it. And it's lactose free. It's engineered. To me, I think of it like a Cheez-It. Like, you can't just have one. This thing is engineered. They spent tons of testing to get the formula just right and it's incredibly successful. But he didn't like the Checkoff program because his competition was generic, when he's trying to sell you a premium milk. And so he allegedly helped finance a secret lawsuit to abolish Checkoffs, that went up to Supreme court. Didn't win. So, he seemingly got into bed with the Checkoffs. So, keep in mind, you have family farmers going broke in Wisconsin paying into a program. He gets some of that money for his personal gain to establish Fair Life and on top of it this Fair Oaks tourist complex, he got money to advertise his industrial model. This industrial model, by the way, that's driving the family farm into bankruptcy.

AUSTIN FRERICK: To me, the most wild part of this whole story though is these things called manure digesters, which is when a cow-- a family farm with cows on land, she's defecating. When she defecates on land, she's fertilizing her feed. When you shove them indoors, which Mike and Sue do, in their industrial operations, first of all, you need fossil fuels to grow their food. But on top of it, when you put them indoors and you pull their manure, when it breaks down in a pulled environment, it creates additional methane gas that is not produced when it's on pasture. So, this industrial model actually makes additional climate changing gases. What he did is he used-- he took that money that used to advertise Got Milk and realized that these campaigns weren't really working. But I argue, essentially as we privatized our land grants, this Checkoff money is financing junk science. These manure digesters.

AUSTIN FRERICK: So, you're seeing tons of USDA money being thrown into them, Checkoff money being thrown into the junk research saying, I think Mike got tons of media attention saying, "hey, I'm using cow poop power to power trucks, " and all this kind of stuff and it's, like, "dude, you're solving the problem of your own creation, using money from family farmers who didn't have that problem, who are going bankrupt."

KAYTE YOUNG: So, in case you didn't catch all of that, the McCloskeys have now embraced the Checkoff system because they've managed to get it to work for them. They got Checkoff money to promote their agro-tourism at Fair Oaks Farm and they got Checkoff money to develop what they call the manure digester, a new technology they developed in response to the backlash that the industry was receiving around climate change. Industrial dairies like Fair Oaks are responsible for methane gas, which is an extreme driver of climate change. The manure digester was supposed to be a solution to their methane problem. It's basically a big tank where all the manure from all the cows is stored for a few weeks. During that time, it's heated so that bacteria can thrive and consume solids. The system captures biogas produced by the manure and converts it into methane, which can be used as a source of energy. What's left in the digester is applied to the fields as fertilizer.

AUSTIN FRERICK: Agriculture is second largest contributor to the climate crisis and dairy's up there with beef. But this model is, how do we produce more and more industrial milk? And so instead of being, like, well maybe we shouldn't do industrial dairy milk from our wetlands or maybe we shouldn't do it in New Mexico in the desert. It's how do we finance junk science to justify our business model? That's all this is. Like, let's not complicate this. They basically pull this manure and they try to capture the methane gas that's produced from it. Get a bunch of government money, look at stuff we're doing and then take that manure and spread it on fields. First of all, the fields cannot handle this much [BLEEP], pardon my French. They just can't. It's just too much manure coming out of them. And then Mike and Sue personally have been fined for gas leaking. There's been reports from various non-profits that these digesters leak methane gas and it's just keep in mind you're incentivizing a destructive industrial model. So, you're actually pushing people to do more industrial cows. Whereas there's a reason why dairy operations took hold in upstate New York and Wisconsin is the climate's right for dairy, whereas wetlands aren't.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes. And so the digesters are not even an economically feasible model either for these large scale dairy operations?

AUSTIN FRERICK: I put them in the same category as ethanol. And anyone that thinks ethanol is good for the climate thinks the world is flat in 2024. The conversation on this stuff is over. I mean that's, honestly, the saddest, angriest part I have is not only are we not doing anything, we're making the situation worse. I mean you have people, you have the Secretary of Agriculture saying with straight face in 2024, let's put ethanol on airplanes. I'm sorry, it's June and we've having a heatwave and every June is going to be like this going forward, guys. It's going to get worse and worse and worse and it's all because you just want to be a lobbyist again. A family dairy farmer, they don't make local contributions. Maybe they give $100. They don't have time to buy off a politician. They're milking their cows two times a day. And you create these Barons. It corrupts the political system and you get these cartoonish, broken realities like this, and on top you get all the hacks that do their bidding.

AUSTIN FRERICK: I mean I talk about-- I think one of the most corrupted academic disciplines in America right now is agriculture economics because there's just so much corporate money sloshing around, financing this junk science or people validate-- I mean what I realized writing this book too is every industry has their go-to hack. In Iowa, I mean I name his name, Dermot Hayes. Every time they want to speed up the kill lines to an already dangerous occupation and make it more dangerous, he's always there saying, "oh yeah, this is great for hog farmers," which by the way, really just means ten people that control the hog industry. But he doesn't disclose to you that he takes money from the hog industry or that he actually does business transactions with my Hog Baron. That, to me, is where my anger really kicks in, is not only are you destroying your community, your area, this is all of us at this point with the climate crisis.

KAYTE YOUNG: But let's return to Fair Oaks Farm and to the manure digester. Though they might look good on paper, without massive government subsidies, the digesters make no sense financially. Another problem is that they're prone to leaks and in some cases the digesters have exploded. And there are other dangers.

AUSTIN FRERICK: The dirty secret of industrial dairy is it's mostly done by undocumented men and writing this chapter, including the barn you go through, like the one I toured as a tourist at his attraction, someone died in it, an undocumented worker died. He was sucked into this manure digester and died in, honestly what sounds like a horror film. This was never disclosed until, I was actually shocked. I found it in the [UNSURE OF WORD] reports. These undocumented men run these empires. I mean a big theme in my book is a lot of these Barons cosplay as farmers, but Mike and Sue claim residency at the Ritz Carlton in Puerto Rico, likely for tax reasons because they sold Fair Life to Coca Cola. So, who is the farmer here? Is Mike and Sue the farmer, who live at the Ritz Carlton? Or is it the undocumented men doing the farming, the actual farming?

AUSTIN FRERICK: And on top of it in a lot of these industrial dairies, they tend to be the largest employer in the area. They're almost like modern day feudal lords. They run these areas. There's been stories, reports out there, and I'm not saying Mike or Sue did this, but generally speaking industrial dairies, you know, they'll put, not only are they the employers of these undocumented men, they tend to also be their landlords. So, they'll put them in old farmhouses, you know, 12 to a two bedroom, according to This American Life episode. So, it's just, like, incredibly dark. I don't know how else to say that. I mean the narrative they sold and what you see versus reality are so separate.

KAYTE YOUNG: And let's not forget Fair Oaks is a tourist attraction. It's been called by Food and Wine magazine, "The Disneyland of agricultural tourism". There's a hotel on site and bus-loads of schoolchildren are routinely brought to Fair Oaks for farm tours.

AUSTIN FRERICK: I ended up being put up with the school group from Indiana on my tour and they kept telling you how happy the girls were inside these metal sheds. And I just realized these kids will never know what it's like to drive a county road and see a cow on pasture. You know what I mean? Like, they don't realize what we've lost and just the sadness of this, like, these cows live in basically an Amazon warehouse all day and that's all they'll ever see.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes. I mean it really actually surprised me that they were giving tours through one of the warehouses. Like, I would imagine how they would do it is have the, sort of, farm, agro tourism. They would have cows hanging out in grass or in a little pen where you could pet them at a petting zoo or something, you know. And that they would try to put forward that old-fashioned pastoral scene of raising animals or raising dairy cows, but they're actually showing off this industrial model and defending it, which I found that really surprising, especially because when you drive by, I haven't been there, but I have driven by it a number of times and when you drive by it it does look like farm Disneyland, like you said. You know, it just looks like it's a sweet place to visit and there's lots of fun things to do there and I just wouldn't think of driving through a warehouse filled with animals packed in like that standing in stalls to be fun at all.

AUSTIN FRERICK: There's a [UNSURE OF WORD] out there. There [TALKING OVER EACH OTHER] has a water park.

KAYTE YOUNG: It stinks.

AUSTIN FRERICK: You know what the funny part is, Kayte, I can't smell, but even like, I remember it was bad. I mean even their namesake Fair Oaks. I mean first of all, the operation next to the interstate because they move so much industrial milk, so they always want to be near an interstate. The name itself is from a little poor town nearby and you're, like, God, they sell so much. Here's this poor little town that just smells like, pardon my French [BLEEP]. It's a really unnerving place. I mean it really says so much about this gildeness of this era of, like, I can't say this enough. I mean they were in Food and Wine. I mean she was named Woman of the Year by, I believe, Good Housekeeping. I mean they got a lot of good media attention. But to be fair, I mean I don't want to belittle, punch down any journalists, mostly these journalists are working for pennies on the dollar. I doubt very few of them visit the operation themselves. They're probably given the story. They were probably freelancers. And it just goes to show you how long Mike and Sue got away-- and honestly it wasn't until Florida Man popped their bubble a little bit when they did an undercover operation, this Florida Man did, uncovered a lot of animal abuse in their operations.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes, I remember when that happened because it definitely did get local coverage here as well.

AUSTIN FRERICK: But nothing changed. I looked up all the grocery stores that pulled their shelves, pulled their milk and Chicago put it back on. I saw some line on Wall Street leak their sales data. It went down a little bit, but then it soared. It's been soaring. And then they promised to do better but then Mike helped design the Animal Welfare Standards, as I note in my book, and so I mean that to me is, kind of, one of my big points of this book is we just gotta change structures, you know. It's going to require regulations to get these things to behave well, you know. The second you treat cow manure like human manure, this model's not economically viable. I mean there are just so many basic little things not being enforced here that allows someone to do this. I mean something I really learned writing this book is you become a Baron because you're willing to cross ethical lines most people aren't willing to cross. Most dairy farmers weren't willing to do this to their cows, or workers.

KAYTE YOUNG: This is a good time for another break. We'll be back in a moment with more from my conversation with Austin Frerick, the author of Barons: Money, Power and the Corruption of America's Food Industry. Stay with us.

KAYTE YOUNG: Kayte Young here. This is Earth Eats and we're back with Austin Frerick, author of Barons: Money, Power and the Corruption of America's Food Industry. Austin has a background in anti-trust policy. I asked him if that was a driving force behind this project.

AUSTIN FRERICK: The thesis of my book really is my coffee chapter. Like I said earlier, the goal of the corporate executive is monopoly. You have a tension between government not wanting monopoly because that's bad for farmers, bad for innovation, bad for workers and business wanting it. It's just so clear the skis have gotten out of hand here. They've gotten too far ahead and things are just out of whack. I think that's also why there's so much anger. Part of being people like my mom running your own business or being a family farm is you're your own boss. You do your own thing. Now for many people now, they're just low-wage workers for these Barons and anyone that goes to a family dairy farm knows these cows are like pets to them. They know the personality of every one. They know them intimately. But now, if you work for a Hog Baron, ten percent of hogs die inside these metal sheds. So, your job essentially is to go in there and haul out the dead pig bodies and throw them into a dumpster. Imagine what the trauma that is. You know, what used to be joy is now cruelty you have to deal with. Or like the animals aren't happy either. I mean that's a whole under appreciated thing too.

KAYTE YOUNG: Oh, yes, I mean I'm, kind of, avoiding the discussion of the animals but it's at the heart of it for a lot of people, I think, is just, it just feels like life out of balance or something.

AUSTIN FRERICK: Yes. I mean but there's always a course correction. I mean the little thing I do, besides we're paying more is we're paying more for junk. I mean I do little tastings for people. Like, take dairy, input matters. You know, when a cow eats a bunch of different grasses, she's going to make a better tasting milk than the one that's inside most of all day, you know, where she eats corn. And people notice that. You know, like that Driscoll berry, that berry's not engineered for taste. It's engineered for durability and shelf life. It's pretty, but it's bloated and tasteless, whereas, you know, a strawberry from your backyard is just so lovely.

KAYTE YOUNG: When I read the coffee chapter in Barons, I was shocked to learn that so many brands that I thought were independent coffee producers were not. I shared with Austin that when I think of big coffee, I think of Starbucks and they are big coffee. Starbucks is everywhere. So, when I'm looking at coffee at the grocery store and I want to avoid Starbucks because of their monopoly, I choose Peets. I remember visiting Peets, a little shop in Berkley, California years ago and I thought well maybe they've expanded their distribution nationwide, but I still saw them as independent, as Peets. Then I found out reading Barons that they're just one brand name in a huge coffee conglomerate based in Germany called JAB Holding Company. Not exactly a household name. I was so disappointed to learn this.

AUSTIN FRERICK: I had that happen with Intelligentsia, which is a fancy Chicago coffee company. And even, any time I fly in and out of Iowa, I always have to connect through O'Hare. There's this place I love to get my lunch at and they always advertise their local providers and they always advertise Intelligentsia, still on their board to this day and you're, like, "guys, this is not local." So, I really set that chapter up as a dichotomy between this history of anti-trust in America which goes back to the Louis Brandeis. He was a Supreme Court judge who really ushered in a century ago an anti-monopoly framework in America, where we want to avoid concentrations of power because he saw what it does to the system. I mean he was a corporate lawyer. I mean it wasn't like he was unradical or anything. He just saw, especially inorganic growth, is what he really was afraid of. No company buys another company for pro-competitive reasons. And so he made, essentially put up guardrails to really make that hard.

AUSTIN FRERICK: What happens in the 80s with the election of President Reagan was Reagan's Supreme Court nominee, Robert Bork really ushered in an academic framework that basically dismantled that Brandeis framework. It was called the Consumer Welfare Standard, where essentially companies could buy another company if you could show that prices went down for consumers. We just think, I can find any economist give me those numbers to say that. You know, that's easy junk science and actually very lucrative by the way, for a lot of economists. Where most economists who do this work make more money doing that work than they do from their fancy University at this point. An under appreciated fact which they don't usually disclose. But the other thing is it's just a massive consolidation.

AUSTIN FRERICK: Truly the biggest ray of hope I have in this book is President Biden appointed a young woman named Lina Khan to the Federal Trade Commission and she wants to return us back to this Brandeis model, where we avoid concentration of economic power. I mean she's the one filing all these anti-trust cases against big tech, stopping, you know, or at least challenging the Kroger-Albertson merger. She can't do that in meat packing because US meat packing and anti-trust authority is actually given to USDA. And the fact is I would argue Lina Khan has been President Biden's best vocal appointee. I think one of his worst is Secretary Vilsack. And the fact is that the meat markets, these last four years, have gotten more concentrated. My Slaughter Baron has bought a company. Cargill got back into the poultry business. Tyson's bought a company. And at the same point, Walmart, from being gouged by the meat companies, it's making its own massive vertical plays in the beef packing. It's building a massive beef slaughtering house out now in Kansas right now.

AUSTIN FRERICK: But I want to say just to wrap up on coffee, a big point of this chapter is actually I think lost history is how much monopolies contributed to World War II. Monopolies financed fascists. Hitler's largest donor was a company called IG Farben. There's a fantastic book called Hell's Cartel about this. IG Farben was a chemical company. Hitler walked into the room and said, "I want to help. I don't mean the crazy stuff, I want to help you sell more chemicals." They're like, "great, here's a big check." Honestly crucial to his election. The final pre-election in Germany. After World War II, Congress commissioned a report, how did this happen? And one of the key findings were that point, monopolies finance fascists. This secret German family, the British tabloids discovered a few years ago, have a very dark Nazi past to them. They atoned for it, said we're sorry, made some charity contributions, but right before I went to press, I kid you not, the Wall Street Journal reported that they are still selling Peet's coffee in Russia, which I would argue Putin is the closest thing we have to a modern day fascist. So clearly your words mean nothing.

AUSTIN FRERICK: The scary thing about their entry into the coffee market is two things. One, it's what Brandeis feared most. It's inorganic growth. It wasn't like they're selling the best coffee. It's just they had a ton of money, so they would essentially buy up what was a competitive industry and they saw a chance to make a cartel. The person who's going to get squeezed here the most are going to be the coffee farmers in Central America that used to have 20 different buyers for the coffee bean, now just have one. And the second thing is, with this family, is their whole investment strategy is really, it's monopoly. Instead of investing in stocks like most people do, they make these monopoly plays. So they did this in coffee and their new play right now is actually in veterinary clinics. They've bought like 1500 local veterinary clinics to roll that up and they're buying a bunch of pet insurance places because they realize that people are a little irrational with their money when it comes to their animals and so they see a very lucrative market to gouge people. And that's what they do.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes, that is definitely a lucrative market to gouge people.

AUSTIN FRERICK: That's the scary thing is, I mean you see this playbook happening all over the American health-care system right now. Writing a book like this means you talk to a lot of people who've been through a lot, you know. I mean the dairy farmers who tried really, really hard to keep it on and they don't realize the system was designed for them to fail. They blame themselves. But at the same time too is you meet a lot of people doing it right. You just realize it's a few greedy people holding us back. So, it's, kind of, a two-edged sword where you have to take on all the darkness, but you also see what it really could be. I personally have to focus and gravitate towards what the system could be because right now no one's articulating a positive vision especially for rural America. What should the real corn belt look like?

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes. Could you talk a little bit about that since we're coming to the end and I don't want to end on a dark note.

AUSTIN FRERICK: I think of ethanol. The ethanol markets right now, it's like watching Wile E. Coyote chase that bird off the cliff because it's ethanol is going to die. I mean cars are going, the EVs and hybrids and people don't realize the largest corn now is ethanol. So, the question is what's going to happen? I mean that's why industry,people like Vilsack are trying to put it in airplanes is they see the writing on the wall. Even SUVs, I mean you've seen SUVs get 60 miles a gallon. That's half the ethanol they used to consume. My hope is we use this coming moment, where ethanol meets its maker, to put animals back on the land. It's better for rural communities, it's better tasting animals, it's better for the environment. So, that's what I really want to focus on is putting animals back on the land, but also more regionalizing these food production systems. I mean you have so much of your produce. I mean this Farm Bill has pushed so much produce off the short and it just makes bad tasting produce, especially the Midwest. I mean I just don't think people-- we have such good soil, and I say this as someone who's lived on the east coast and realize how hard it is to grow good produce or a good tomato. It's just there's no excuse for why I can't get a good tomato at a sandwich shop right now in the Midwest, you know.

KAYTE YOUNG: What makes you think that getting animals back on the land is a possibility? Is it just what you're saying about we are going to come to a crossroads around how much corn we're growing and how we might rethink that? Is that what you're saying? You're saying, okay there's all this land that we're currently growing corn on, let's think about what else we could do with that land.

AUSTIN FRERICK: The dirty secret is the dairy industry hollowed out its voter base. You used to have a bunch of rural families, family farms on a street, those were voters. Now they're gone. The modern Farm Bill coalition was formed in 1960s America. I mean the suburbs were not a part of that conversation. To me, you're actually seeing the modern Farm Bill coalition break down in front of us. I mean they cannot pass a status quo Farm Bill. And I'm at the point now to just not support it. We should subset the Farm Bill. The Farm Bill right now picks favorites and it picks corn and soy as favorites. That's why it takes money to eat healthy in this country. If you grow carrots, you don't get anything. You want to grow corn for cars, you get a ton of welfare. And that system is just so rotten and corroded that it's breaking down. Even though Republican Party can't muster the votes. So that to me is the hope.

AUSTIN FRERICK: But also you're just, I mean I've done a lot of right wing press, or Republican outlets and people get it. They see what's going on in the store. It just doesn't make sense, like if there's one graph I could include it would be beef markets. What you pay for beef in the store goes up and up every year, yet what the farmer gets is flat. And honestly that's a political opinion piñata, saying hit me, hit me. And so I just feel like things are out of whack and at some point, you know, things are just going to have to return to earth.

KAYTE YOUNG: As we were wrapping up our conversation, I asked Austin Frerick to read a passage from his book. This is from page 178 in Barons.

AUSTIN FRERICK: Healthy markets are not a natural phenomenon. As a society we make decisions about how markets are structured, about the rules that govern them and what constitutes fair play, about who holds power and who does not. Once we have acknowledged that these decisions have shaped the food system we have now, we can opt to create a different system that better reflects our values. I love this one. And as weird as it sounds, this comes from meat packing. Slaughterhouse workers. The story of slaughterhouse workers this last century really showed this point to me where as a society we saw them, how exploited they were in Upton Sinclair's, The Jungle. We decided as a society we wanted more, we wanted better. So, not only do we trust bust, but we made regulatory changes that empowered these workers to make what was an exploitative occupation a solid middle class living. My family benefited from that. We had that American dream because of those choices we made as a society.

AUSTIN FRERICK: But what's happened in the second gilded age, which is what I call this moment, is that we've seen a systematic assault by industry to undermine those gains and revert this to a low-wage occupation, where now like the MI folks, you have tons of slaughterhouse workers who work at [UNSURE OF WORD], who live two families to a 2-bedroom Section 8 housing. That's where we are, but we can make decisions. These are choices. These are choices we make to create Barons and we can make choices to de-create Barons, if that makes sense. There's no free market here. That's actually my favorite thing. The only free market I see in the food system is that farmer's market farmer. They're getting no welfare. They're getting no Farm Bill stuff. And they're actually competing against the person across from you selling the same carrot. Even the grocery store, you think there's a free market. There's not. They call it mafioso capitalism because even the shelf space you see, people are paying for your eyeballs. There's a whole game of shenanigans going on there.

KAYTE YOUNG: Do you have a vision for anti-trust policy changes that could begin to make a difference?

AUSTIN FRERICK: Well, meat packing we've done this before. I mean that's the easiest one to start with. We've broken up these cartels. We've broken up these trusts before. So, I mean part of it is just there are certain mergers that should not have been approved. I mean let me actually step back. JBS is wild to me and meat's kind of what I really know and I didn't even know this until I wrote this book because this news dropped right before the 2020 election. They pled guilty to bribing over 1800 Brazilian politicians to become a monopoly. I'm not talking campaign contributions. I'm talking bribes, like Manhattan level apartment bribes. And we let them keep it. We let them keep the empire. Not only did we let them keep it, Secretary Vilsak given them USDA money. What world are we living? You know what I mean? Imagine do you want to great-- make a monopoly, we'll bribe our way to it and we get to keep it. I mean the whole point of that chapter is they're the closest thing we have to a modern day criminal organization in corporate America. So, let's start there. Let's just actually not let criminals have monopolies. What a radical concept.

AUSTIN FRERICK: So, we should always start with the framework of how do we design a system to avoid concentrations of power. Because if the goal of any business is monopoly, how do we put in the fence and guardrails that keeps competitive markets?

KAYTE YOUNG: Yes, and so there's a lot of those guardrails that are needed, not just one type.

AUSTIN FRERICK: Yes, even a simple thing like in the meat markets, spot markets, like hog barns. I don't know if any of your listeners have ever been to a hog barn or anything, but that's like Ebay for pigs. You take your pig there and people bid on it. First of all, part of that is just social. It's good to see people. But second, that's where real price discovery happens. Here's the thing, companies don't like that. They try to move you to production contracts because you don't know what anyone else is being paid and that's when they have leverage over you. Let's require spot markets. I mean that's what cattle ranchers really want right now, is they want to maintain the spot market they have, because they saw it collapse in hog and chickens. And so, I mean that's also what my Coffee Barons are trying to do with the coffee market. They're trying to kill the coffee spot market. Who doesn't want price transparency? I mean you got the new little things of like, how do you think from a structural thing? How do you maintain these things? Because it's not just also about price transparency, but it's also about the culture. You know, it's having a cup of coffee with a neighbor and then bidding on hogs.

KAYTE YOUNG: And maybe that coffee will be from an independent producer. Honestly, after reading Austin Frerick's book, I now only want to buy coffee from local roasters who I know are independent and who are ethically sourcing their coffee beans.

KAYTE YOUNG: I've been talking to Austin Frerick. He's the author of Barons: Money, Power and the Corruption of America's Food Industry, released in 2024 with Island Press. There's so much more in the book that we didn't get a chance to touch on, like Cargill, the Grain Baron, or Driscolls, the Berry Baron. I learned so much about our food system. Perhaps more than I wanted to know, but as Austin points out, you need to understand how power is amassed before you can deconstruct power. You can find links to Austin Frerick's work on our website EarthEats.org.

KAYTE YOUNG: That's it for our show this week. Thanks for listening. I will see you next time.

KAYTE YOUNG: The Earth Eats team includes Eoban Binder, Alexis Carvajal,

Alex Chambers, Toby Foster, Leo Paes, Daniella Richardson, Samantha Schemenaur, Payton Whaley, and we partner with Harvest Public Media. Special thanks this week to Austin Frerick and Island Press. Earth Eats is produced and edited by me, Kayte Young. Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from Universal Production Music. Our executive producer is Eric Bolstridge.