(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington Indiana, I'm Kayte Young and this is Earth Eats.

ROBERT FREW: Our overall mission is to grow a variety of food that is adapting to the changing climate.

KAYTE YOUNG: This week on our show we explore two approaches to sustainable agriculture, working with nature to grow food, one in Puerto Rico and one here in Indiana. We visit a Kimchi stand at a farmers' market in North Carolina and Harvest Public Media brings us stories about black farmers in Oklahoma and in Iowa, and a row crop farmer experimenting with new methods. That's all just ahead in the next hour here on Earth Eats, stay with us.

(Gentle piano music)

KAYTE YOUNG: Earth Eats comes to you from the campus of Indiana University in Bloomington Indiana. We wish to acknowledge and honor the indigenous communities native to this region, and recognize that Indian University is built on indigenous homelands and resources. We recognize the Miami, Delaware, Potawatomi, and Shawnee people as past, present, and future caretakers of this land.

Renee Reed is back with Earth Eats news. Hi Renee.

RENEE REED: Hi Kayte. I've got a couple of stories from Harvest Public Media this week. Pork raised in the United States feeds people around the world. China, Canada and Mexico are the biggest overseas markets, and U.S. officials and farmers are courting other countries. U.S. pork producers had great hope for 2020 in part because China was still rebuilding its swine herd after a massive disease outbreak. But a single American trade war that had barely cooled suggested over reliance on China could backfire. U.S. Department of Agriculture undersecretary Ted McKinney said some trade bailout money went into developing new markets.

TED MCKINNEY: We're leaving no stone unturned. If we can sell an extra container of pork somewhere, that's an extra container of pork that came from somebody's farm or ranch and that's what we want to do.

RENEE REED: McKinney sees promise in a pending trade deal with Kenya and says other African and south east Asian countries are also on his radar. He made his comments in a webinar sponsored by the Missouri based AG policy group, Agroplus.

President Trump's phase one trade agreement with China isn't meeting its targets. The agreement signed in January was ambitious to begin with. But the most recent data shows that by the end of September, China had only bought about half as much as what was targeted. Chad Bown is a trade expert with the Peterson Institute for International Economics. He says it's very unlikely that China will ultimately meet its purchasing goals.

CHAD BOWN: They would have to buy a lot of aircraft in the last three months of 2020, you know big ticket items like that. They would have to buy a lot of soybeans.

RENEE REED: Bown says there are many reasons China is falling short, including the grounding of some Boeing planes, animal disease outbreaks, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Those stories come to us from Dana Cronin and Amy Mayer of Harvest Public Media. For Earth Eats news, I'm Renee Reed.

(Earth Eats news theme)

KAYTE YOUNG: As harvest season winds down, one farmer in North Iowa is collecting data from his first year experimenting with a combination of crops and livestock. He calls it "stock cropping". Harvest Public Media's Amy Mayer introduces a man trying to improve upon old traditions with modern technology.

AMY MAYER: Zack Smith is walking through alternating strips of pasture and corn that he planted this year.

ZACK SMITH: Well this is our answer for putting diversification and multiple species back on the land, and we're gonna have a four-ring circus was my idea of animals parading through grazing, laying their manure down.

AMY MAYER: He's motivated by the need to reduce the environmental impact of conventional farming. Smith and a business partner designed and built a mobile barn that moves his livestock through a pasture area each day.

ZACK SMITH: We call it the Cluster Cluck 5000 is the model name.

AMY MAYER: Goats and sheep chomp the tall sorghum sudangrass out front, pigs root around...

(pigs snuffling)

and dose behind. Then chickens pass through pecking and keeping the flies at bay. The roof offers shade and is angled to collect rainwater. Smith knows pasture raised livestock on a grain farm seemed old fashioned. But he's leveraging technology to make the revival modern and practical - webcams, solar panels, autonomous movement.

ZACK SMITH: You know you can have an app on your phone and say move the farm and hit the button and Siri would make the barn move ahead for you.

AMY MAYER: Smith's commitment to technology extends to his series of YouTube videos about the project.

ZACK SMITH: What is cracking up? (rooster crows) What he said, stockers. Zack the stock cropper being serenaded by the cocka-doodle-dooing of a rooster.

AMY MAYER: He says his years touring in a band left him comfortable in front of an audience. But he's a 5th generation corn and soybean farmer with seed and chemical businesses, still he recognizes that change is the future.

ZACK SMITH: I'm part of the big Ag machine. It's just like anything, it's the Titanic. It doesn't just spin on a dime.

AMY MAYER: He decided to put some of his trade bailout and coronavirus relief money toward testing stock cropping. His experiment pushes multiple ideas at once. Let's start with the crops. Key cooperative agronomist Ben Hollingshead has been following Smith on social media. He says the pasture plants improve the soil.

BEN HOLLINGSHEAD: The more species of different types of roots that you have in that soil, make that soil more resilient, more apt to be able to hold nutrients.

AMY MAYER: But Hollingshead said the rub is this - no matter how good it is for the environment and the future, any proposed change can't threaten profit. Smith knows this. That's why his second goal is to cultivate customers for his pasture raised meat. Practical Farmers of Iowa Livestock program manager Megan Filbert says it's a sound idea, but the meat is going to cost more than shoppers pay at the supermarket.

MEGHAN FILBERT: You know due to the majority of Iowans care enough, do they actually want this? And I'm not sure that's the case.

AMY MAYER: This winter Smith will evaluate soil on water quality, and he'll calculate what he expects to be a lower carbon footprint for producing meat in his system. He hopes the results will appeal to customers' values.

ZACK SMITH: And I'll hopefully be able to achieve that with marketing to consumers that want to have the experience of seeing their meat raised in this fashion and willing to pay for that.

AMY MAYER: He estimated a farmer with 80 acres could run 30 Cluster Clucks and raise 450 pigs, a couple hundred sheep and goats, and 9,000 chickens. But that would require hiring livestock and marketing staff, plus taking animals to an inspective processor. It could take up to 2 years and 2 million dollars to build a new slaughterhouse. But the investment would foster Smith's 3rd goal; making rural life more viable and appealing.

ZACK SMITH: We're gonna keep doing videos. The harvest has come and gone, we still got the chickens to finish out...

(Music plays out)

AMY MAYER: For now Smith's got corn in the bin and meat in the freezer, most of it sold. The 75 people that came to his September field day gave him confidence stock cropping is resonating. He's filed a patent on the Cluster Cluck technology and hopes to attract even more interest as he continues sharing videos. Amy Mayer, Harvest Public Media.

KAYTE YOUNG: Harvest Public Media reports on food and farming in the heartland. Find more from this reporting collective at HarvestPublicMedia.org.

(Electric piano transition music)

MARISSA REYES DIAZ: We had start(ed) to meet to get together, to find a way to do farming together in 2015. In 2017 in May that we made the agreements and everything so we are just getting there. And then in September the hurricane just came. And we were hit first, Irma and after two weeks we received Maria.

KAYTE YOUNG: Marissa Reyes Diaz is one of the founding members of Güakiá

MARISSA REYES DIAZ: Güakiá Colectivo Agroecológic or agroecology collective. Güakiá means "ours" or "us" in Taíno language that is from our native Indians of the island.

KAYTE YOUNG: Güakiá is a farming collective in Puerto Rico based around the principals of agroecology. Marissa Reyes Diaz and Stephanie Monserrate Torres visited the Indiana University food institute in 2019.

STEPHANIE MONSERRATE TORRES: We are an agroecology collective, so we are farming, trying to imitate nature and how it works. Agriculture is already a really invasive way to do how we eat. But in agroecology we try to just imitate the earth, but as well it has to have social connection, social integrated with the agroecology projects.

So we knew we had to have some sort of social component to our project, so we're going to farm in the community will eventually see we're growing stuff and they'll come to us, because it looks pretty. So they'll come.

But after the hurricane didn't need that much food as help for first response. So our project kinda went towards just building community. A lot of people just needed to tell their experiences after the hurricane. So we just sort of went towards what felt right basically, which it was helping the community and other communities and other farmers helping their farms. Cause we didn't have, we barely had three months in the farm. So now last December is that we really started to grow food, finally.

KAYTE YOUNG: That was Stephanie. Marissa and Stephanie took an agroecology course together which ended up being the spark for their collective.

STEPHANIE MONSERRATE TORRES: In the workshops we took the agroecology course. We were 30 people going together into some small plot and building it into a food garden, into a food forest. And it just seemed kind of nuts to do it alone after the workshop was done. And it for us agroecology is not just farming or the community as well, there's a lot of social injustice that the agroecology movement stands up for or is a first response as well.

KAYTE YOUNG: Marissa noted that most of the food that's being produced in Puerto Rico using sustainable agriculture is going to restaurants, because that's where the money is. At Güakiá they plan to produce food for restaurants and for CSA's but also to make the food accessible to the people living in the community close to the farm.

MARISSA REYES DIAZ: So the idea is not just to produce food, it's to produce for everybody.

STEPHANIE MONSERRATE TORRES: And for us as well, I need to eat (laughs).

KAYTE YOUNG (INTERVIEWING): So the main industry in that area is tourism, so there's more restaurants and hotels and things like that?

MARISSA REYES DIAZ: Yeah, more hotels, more restaurants that are not accessible for Puerto Ricans or obviously low-income Puerto Ricans. That's the majority of what we have near our farm.

STEPHANIE MONSERRATE TORRES: We're in the north part of the island, it's about 10 minutes from the beach. But it's a low-income community. But it's not a low-income municipality. If you know like... we have a lot of resource, a lot of tourism, but it's not such a paradise for Puerto Ricans who live there.

So we have low-income communities, after the hurricane they were one of the last ones... last ones that got their streets cleaned, the last ones that got water.

KAYTE YOUNG (NARRATING): After the hurricane, after helping with the immediate needs of the community, Güakiá got the word out about their collective using social media. There were organizations in the U.S. looking to offer direct assistance to everyday Puerto Ricans, and one of the brigades working with Güakiá was organized by Science for the People.

MARISSA REYES DIAZ: And they just went to the farm. We stayed in the farm for 10 days and we don't have electricity or water, so we were camping. A lot of people. There were 15 people camping in the farm, so it was a lot.

But we (laughs) but we did a lot, like at the end of the week we were like, "Oh my god, this looks totally different from when it started." And we were able to do a festival, raise some funds, raise the awareness that we are there in the community. So the brigades have been awesome.

KAYTE YOUNG (INTERVIEWING): So did you need to clear a lot of things from the land?

MARISSA REYES DIAZ: We needed to clean a lot, we had refrigerators, beds, cars, you name it. We had cleaned before the hurricane, but after the hurricane it got all again out of hand because everybody was just trying to throw everything away.

KAYTE YOUNG: I was imagining a lot of brush and vegetation that you would have to clear but-

STEPHANIE MONSERRATE TORRES: Also, also we have that because the grass is-

MARISSA REYES DIAZ: 6 feet high, and it's like a bamboo-ish grass, so when you try to cut it the machete comes back to you.

KAYTE YOUNG (NARRATING): So in addition to the brigades and other volunteer groups, they hired nearby farmers with equipment to help clear the land.

(Interviewing) So you have cleared some beds or some rows now, and what do you have growing at the moment?

MARISSA REYES DIAZ: We have banana, plantain, cassava, beans, we get some corn, papaya, ginger, turmeric, shallots, tomatoes, sweet pepper, zucchini. I don't know how to name the gandules in English, it's like a bean but different. It's a pretty good one.

STEPHANIE MONSERRATE TORRES: It's dried and cooked like in rice, it's really for Christmas, it's a weed, like arroz con gandules, rice and gandules.

MARISSA REYES DIAZ: And we make this rice, it's the best part of the Christmas thing. Yeah.

KAYTE YOUNG: What kind of seasonings?

MARISSA REYES DIAZ: We made a sofrito that is a mix of onions, garlic, sweet pepper, pepper, salt, oil, cilantro, and that's all we just put it in a blender. And we have the sofrito and we use that to cook.

STEPHANIE MONSERRATE TORRES: We use that not only for Christmas but that's our base. That's the base for every dinner, yeah, sofrito.

KAYTE YOUNG (NARRATING): The Güakiá Collective has also maintained and nurtured the connections with the surrounding community.

MARISSA REYES DIAZ: One of the worships that we made in the community was a compost worship. We invite them to separate everything that is trash of the fruit, yeah organic. And we pass every Friday, we pass by the houses and we collect all this organic matter that they separate to do a compost, a community compost in the farm.

STEPHANIE MONSERRATE TORRES: It's like a competition for them too, like whose having more compost or something like that. And so they're eating better, because they want to eat fresh foods now. They don't have that much smell from the trash in their house, they spend less in their trash bags, and then they feel like they're part of something bigger, that they're helping the island, they're helping the reconstruction of the island. And we have some exchange with them. We give them fresh compost for their plants, or we give them some tomatoes. Like it's a really good compost program with the community. It's really good. And it's going on along great.

KAYTE YOUNG (NARRATING): Future plans for the farm include the installation of solar panels for electricity, a sustainable water source, buildings and infrastructure, and strengthening connections with the community. They also hope to find ways to make the farm sustainable financially. So that the five members of the collective don't need to hold down two or three additional jobs to stay afloat.

MARISSA REYES DIAZ: You know Puerto Rico is a colony of the United States. So just things that could put you into context of why is it that we're doing what we're doing, and why is it so hard? So basically we can't vote for the President. We only have our representative in congress and he also can't vote. He only has a voice, so it's nothing.

KAYTE YOUNG: Stephanie also brought up the Jones act and what it means for Puerto Ricans in terms of their dependence on the United States. Though Puerto Rico's tropical climate makes it suitable for year-round farming, the island currently imports 80% of its food, mostly from the United States.

STEPHANIE MONSERRATE TORRES: All the peasants, all the people that do agriculture in Puerto Rico, they just get out from the farms to work in industry and in factories because what the industrialization moment. So we lose a connection with the land. That's why we get so big person of importations. And we're returning to the land.

(Music)

MARISSA REYES DIAZ: Farming in Puerto Rico, just farming it's such a resistance, so powerful. If we have food, we have food security and we are getting out of the system, so it has kind of all things in it.

STEPHANIE MONSERRATE TORRES: We need at least sovereignty in our food and then we can construct or build something different from the island, but we have to start with the food. Because it's that's is a freedom for us I think.

KAYTE YOUNG: That was Marissa Reyes Diaz and Stephanie Monserrate Torres of Güakiá Agroecology Collective. Agroecology shares many principals with permaculture farming practices. Later in the show we visit with farmers here in Indiana working with the land to grow food in sustainable ways. Stay with us.

(Transition music)

There are fewer than 18,000 black farmers in Oklahoma and many are working second jobs to make a living. But Oklahoma once had a thriving agricultural community. Harvest Public Media's Seth Bodine explains how things have changed and visits one farmer trying to keep his ancestor's legacy alive.

SETH BODINE: Nathan Bradford Junior is filling up buckets of feeds at his home in Bristow Oklahoma. He's about to drive to several plots of land to check on his cows. He explains the name of his business, G Line Meats.

NATHAN BRADFORD JR: Most of the people on this line, on this road, is or was from Georgia and that's my ancestors.

SETH BODINE: As he drives the 80 acres of land he points out the house his grandfather used to live in. He thinks it was built in the mid 1930's and it looks like it hasn't been touched for years, a rusted tin roof and missing wood wall panels.

NATHAN BRADFORD JR: Probably need to take it down. You know it's one of those things` that you really don't want to get rid of.

SETH BODINE: Bradford has about 400 head of cattle. He says there is a lot of work to do because the soil has been degraded after years of farming. So Bradford has been playing a game of catchup, he's been removing trees and planting better grass for his cattle.

NATHAN BRADFORD JR: I can't give up, I gotta make this place better than when I found it. You know they had what they had, they have the resources and I've got an opportunity to make it better and that's what my goals are, and that's what I'm gonna do. It's just gonna take some time.

SETH BODINE: This isn't Bradford's full-time job; he works at a nearby natural gas processing plant - seven days on and seven days off. The rest of the time he's working with the cows.

WILLARD TILLMAN: That's the life of a black farmer.

SETH BODINE: That's Willard Tillman, he's the executive director of the Oklahoma Black Historical Research Project.

WILLARD TILLMAN: A lot of them have it in their blood, they've been doing it all of their life, that's what they want to do. And a lot of times I'd have to say a good 75-80% of all the farmers, black farmers, have a job. You know.

SETH BODINE: That wasn't always the case. Following the civil wars there were 50 established all black towns and one and a half million acres of land. that's more land than anywhere else in the country at the time. The number of black farms has decreased over the past century. Much of that is a result of discrimination.

VALERIE GRIM: The way that many of the black farmers fell behind and eventually lost land was because they could not get the loans in the first place.

SETH BODINE: That's Valerie Grim a professor at Indiana University Bloomington. She says many families like the Bradfords couldn't get loans from banks or the federal government. in fact many black farmers won a class action lawsuit against the USDA in the 90's. Bradford's father, also named Nathan, received $50,000 as part of the settlement. But he says he would have been better off if he'd gotten loans when he was trying to farm.

WILLARD TILMAN: (inaudible)- that'd make you a millionaire today.

NATHAN BRADFORD: Oh shoot I'd be rich.

SETH BODINE: But the elder Bradford says he would have been able to buy hundreds of acres of land for cheap.

NATHAN BRADFORD: It was about $200 an acre at that time or less. But you just couldn't get the money.

SETH BODINE: Things have changed. Nathan Bradford Jr says he's been able to get loans, even though he's had his fair shares of challenges with the Farm Service Agency. He wants to be a full-time farmer by his 50th birthday, 9 years from now. Next step is expanding his business, by opening up a place to process meat like deer. He has a small team where he and his family and producers in the area.

NATHAN BRADFORD JR: When your heart is in it, and you focus that and you want to make it happen, these guys, we can make it happen.

SETH BODINE: Nathan hopes to be open for hunting season. He says there's still a lot to do, but they'll work day and night to make it happen. Seth Bodine, Harvest Public Media.

KAYTE YOUNG: This story is part of a series on Black Farmers from Harvest Public Media. We'll have the second story on black farmers in Iowa later on in the show. After a short break we meet an entrepreneur with a spicy tangy product. I'm Kayte Young and you're listening to Earth Eats. Stay with us.

(Transition Music)

Starting a food business takes a lot of different kinds of work, product development, sourcing ingredients, building a customer base, and of course choosing a hard to forget name. Josephine McRobbie caught up with an entrepreneur who goes by the name The Spicy Hermit.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: The Durham farmers' market is home to a lot of eye-catching booths, filled with crusty loaves of bread, plump strawberries and pillowy heads of butter lettuces. But the Spicy Hermit stand is especially intriguing. Flanked by two large coolers and a display of free samples in white cardboard cups, it's as much science lab as it is produce stand.

TAIWANNA: And here he goes. Crunchy, oh a little spicy and hot. But it has great flavor. It has a little bit of... I wanna say, a little bit of a twang?

(Twangy music)

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Tangy, spicy, flavorful; it's Kimchi. The Korean condiment with a history dating back to around 37 B.C. is made by salting and fermenting vegetables often using garlic, ginger or Korean chili peppers for additional flavor. Eunice Chang is the chef behind The Spicy Hermit's kimchis. She advises marketgoers on which batch to try -- butternut squash, green garlic, sweet onion, or the traditional favorite of napa cabbage.

EUNICE CHANG: The napa kimchi is our spiciest, but it's also our most popular.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: If they didn't grow up with kimchi, visitors to Eunice's booth are often curious as how to use this little jar of preserved vegetables. As Eunice advises, it's great to up the ante of an already spicy creation like salsa or ramen. And when mixed with a fat, the sour and pungent taste of kimchi creates something entirely new and complex.

EUNICE CHANG: Personally, I like to mix it with avocado, and it makes an amazing avocado toast.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Avocado toast might not need a recipe, but cards at the booth include step-by-step instructions for dishes like kimchi and goat cheese ravioli, or kimchi queso. Eunice's partner Brian Owen is often involved in taste testing these creations.

BRIAN OWEN: Those are typically things that on a Sunday afternoon, after the market and after we've had time to rest, we'll think about what to cook on Sunday. and [Eunice will] usually think up some kind of crazy kimchi-inclusive recipe.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: And rest aftermarket is much needed. Eunice flies solo at the relaxed Wednesday market, but on the weekends The Spicy Hermit is a busy team affair, with friends like Cheryl Mitchell-Olds pitching in.

CHERYL MITCHELL-OLDS: I am a kimchi cheerleader. I eat kimchi and I tell everybody that kimchi spices up their life and makes everything they cook better!

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Eunice has fostered a community around her passion for foods. We happen to live in the same neighborhood, and I realized once we met that she was the force behind our local park's delicious but mysterious food truck rodeo. She slings kimchi-infused dishes at local arts and food events and inspires her friends to be more adventurous in their tastes.

MEREDITH EMMETT: I never knew I liked kimchi until I tried Eunice's kimchi,

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Meredith is a neighbor of Eunice's. Eunice is deaf and she chose to write out some of her longer answers for this piece and to have Meredith read them for her.

[Sound of Meredith adjusting her script paper and saying "Oh! I just realized, it's two-sided!"]

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Eunice started making kimchi because she couldn't find any she liked in the area. She sourced her ingredients at the downtown farmers' market.

EUNICE CHANG (READ BY MEREDITH EMMETT): One day a farmer asked me why I was taking copious amounts of napa cabbage and radish and I said I was making kimchi. His face brightened up and he said that he loved kimchi, so I said I'd bring him a jar. Well, he finished the jar in a week, and he eventually convinced me that I should sell it.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: She cites a number of books as inspiring The Spicy Hermit, such as the novel Free Food for Millionaires by Min Jin Lee, and Never Home Alone, biologist Rob Dunn's love letter to the beneficial nature of microbes. She also had a potent memory of her own grandmother's recipe.

EUNICE CHANG (READ BY MEREDITH EMMETT): She's long gone now, but the only time I saw her make kimchi was when she visited us in the States. She'd use the vegetables available to us here and convert it to kimchi. For example, she'd make green cabbage and cucumber kimchi. I haven't been able to replicate it, but my green cabbage kimchi is definitely inspired by her.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: Foods from around North Carolina are central to the Spicy Hermit's portfolio of products.

EUNICE CHANG (READ BY MEREDITH EMMETT): As for southern staples like collards and sweet potato, these are vegetables that grow easily and abundantly here in the South, and there are many recipes that involve using them with spicy, slightly sour flavors, like cider vinegar and hot sauce for collards, so I figured using them in kimchi would be a good example of local preservation and produce good flavor profiles.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: The first step is finding some great core ingredients to use. And there's a very special ingredient, or essence, or activator, added as a person chops and seasons the vegetables to prepare them for fermentation. It's called hand favor, or son mat in Korean.

EUNICE CHANGE (READ BY MEREDITH EMMETT): Every person has a unique composition of beneficial microbes on their hands, and when you make kimchi or sourdough bread, you pass on that composition. So yes, every person's kimchi is different, and yes, some people can just make things taste better (or differently) from others.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: As the vegetables and spices sit in a jar at room temperature for a week or two, their flavor begins to change radically.

EUNICE CHANG (READ BY MEREDITH EMMETT): So for example, a lot of people don't like raw radishes or turnips. But when you ferment them into kimchi, they become sweeter, with a tinge of sour, and it's almost like a completely different vegetable.

JOSEPHINE MCROBBIE: When Eunice was starting to jar and sell her products, she needed to come up with a name. And the Spicy Hermit fit her mission perfectly.

EUNICE CHANG (READ BY MEREDITH EMMETT): Korea used to be called The Hermit Kingdom, so I took the word hermit, and a friend suggested the adjective spicy, which can literally mean using spices, which kimchi does use, or it could also mean sassy. Since I'm strong-minded in my opinions, particularly that of food, and I'm a bit of an introvert, The Spicy Hermit seemed to be a good way to describe myself. Although I also liked the mystery about it, in that a hermit would be practicing food alchemy in a cave to produce rather delicious results.

KAYTE YOUNG: That story comes to us from producer Josephine McRobbie. Find more about the Spicy Hermit at EarthEats.org.

(Transition music)

The agroecological vision that Stephanie and Marissa talked about earlier in the show is compelling and inspirational. A couple years ago I had the chance to visit a farm with a holistic vision, founded on the principals of permaculture. Sobremesa farm is located in the southcentral Indiana, just outside of Bloomignton. The farmers Juan Carlos Arganca and Robert Frew had a larger vision in mind when they started their farm more than six years ago. Robert Frew shares the story.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: The agroecological vision that Stephanie and Marissa talked about earlier in the show is compelling and inspirational. A couple of years ago, I had the chance to visit a farm with a holistic vision, founded on the principles of permaculture. Sobremesa Farm is located in South Central Indiana, just outside of Bloomington. The Farmers, Juan Carlos Aranga and Robert Frew had a larger vision in mind when they started their farm 5 years ago. Robert Frew shares the story:

ROBERT FREW: That really started with one person, and that was Lucille Burtuccio. She was a guiding light for us in understanding the importance of land conservation and caring for wildlife and for an appreciation of native plants. So through her, we started on this journey of really re-creating ourselves, and deciding 'hey, we could probably do something more than what we were doing. Instead of just a backyard habitat, why don't we create a very large piece of land, that's a habitat, that grows food, and has animals, and that we can also create this sense of community around us?'

JUAN CARLOS: We love food and community. I come from a Latino culture in which it's pretty important to be connected with people, and food is one of the best things for that. That's why also, we named the farm Sobremesa. In my culture, when you finished eating you stayed at the table, chatting, gossiping, things like that. And that's Sobremesa, that's what we call Sobremesa. So that's why we are growing all sorts of food here and connecting the food to the community. So, we have the market here, events, we have guests coming.

Also, we thought it would be unique, something we learned from the Amish, you go to their farms and they harvest for you there. And that's what we do here at the market. People come and we harvest for them, they see the produce and they can choose. It's a good way because the food becomes something else. It's not just an item, it has history, love, sharing information, and you get to know that person that is eating your food. It is really great.

KAYTE YOUNG: so you haven't already harvested for the market, it's as people come, you might go out into the garden and pick things?

JUAN CARLOS: Some of the things we do harvest early in the morning, but we have some chairs, so when people come here, they breath and they wait. Or they come with us. So, it's an adventure I would say, you need your time, and also they meet other people who are buying stuff from us here, so it's an event I would say, too.

ROBERT FREW: The Market is on Sunday from eleven to six, and we open the gates at the road, put out signs and wait [laughs]. I think it's a way for people to better connect with their food. Because they meet the farmer, they see how it is being grown, and they see the entire ecology of the piece of land around the food.

We wanted a central feature at the farm, and we decided since we were both into refurbishing and salvaging things, that we would find a barn that was going to be torn down up in Dyer Indiana, and we hired an Amish crew to disassemble the barn, put it on trucks and bring it here and reassemble it--in mostly the same way that it was, with a few alterations.

We got together with a sound engineer from IU who suggested that we remove one of the lofts that had originally been in the barn, and to eventually create a solid surface floor, which would help with better acoustics in the barn because our goal was to have concerts there and different musical events--really to help educate people. Which again, is part of the mission we're carrying on from Lucille, to help people connect with a piece of land and to understand the heritage of farms in Indiana. And in the case of the barn, the importance of conservation, of preservation of an important piece of architecture that really roots us here.

KAYTE YOUNG: Sobremesa also offers two lovely AirBnb spaces, and they host campers, interns and Woofers-- people who travel to live and learn on organic farms.

They've also connected with the local elementary school in Unionville.

JUAN CARLOS: They have an amazing idea for the whole school, in theme, it's called EARTH, they have a garden--that school is amazing.

We prepared a workshop to create a mound, Hugelkultur is the word they use in Germany, but it's pretty much a big raised garden, using some materials you have right there, on your place. There were sixty-something kids, and they were fantastic, oh, we loved it. There was one seven-year-old, came to me and said, "I could do this for the rest of my life!" And that really was the best.

KAYTE YOUNG: So they built the mound?

JUAN CARLOS: We divided all the kids into three groups. The ingredients we had were branches, paper, soil, cardboard. So they all went through the whole process. They used shovels, all the tools, wheelbarrows, they worked incredibly. I told one of them, "you're hired!" because they didn't want to stop, they went on and on.

KAYTE YOUNG: They also hosted a group once called Reimagining Opera for Kids, presenting a food-themed opera in the refurbished barn for a group of students from Unionville Elementary.

There's so much happening at Sobremesa farm, too much really to cover in one episode. But we'll check back in with Robert and Juan Carlos later in the show to hear about why they keep a special type of fowl on the farm. I'm Kayte Young, this is Earth Eats, stay with us.

(Promotional music)

RENEE REED: Make sure you never miss an episode, subscribe to our podcast. It's the same great stories in your podcast feed. Just search for Earth Eats wherever you listen to podcasts. While you're there, please leave us a review. We love to hear from you and it helps other people find us.

KAYTE YOUNG: Most Midwest farmers are white. In 1900 there were about 300 black farm families in Iowa, only about half remained by 1970 and the numbers continued to decline for decades. Despite some recent increases, Harvest Public Media's Amy Mayer explores why there are few black farmers in Iowa today.

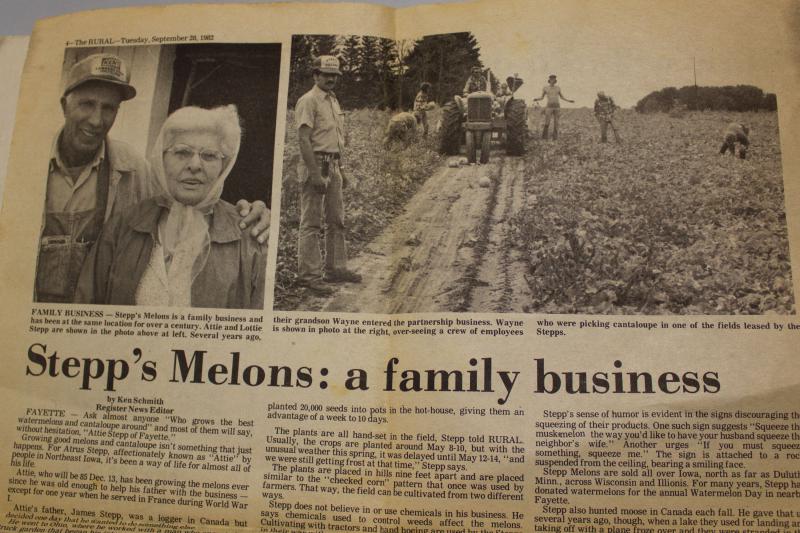

AMY MAYER: Driving along highway 150 in Fayette County Iowa, you see a giant propane tank painted to look like a watermelon. It's the site of a produce stand, owned and operated by one black family until the 1990's, the family of Atrus Stepp.

CHARLES DOWNS: Everybody’s got good things to say about Attie.

AMY MAYER: That's Charles Downs, he's white and bought the place from Stepp's daughter. Stepp died in 1993 at the age of 97.

CHARLES DOWNS: Conservatively, I’d say it’s been here 80 years, at least, and it’s probably... maybe a hundred.

AMY MAYER: Stepp's family traces roots to a small but thriving African American farm community. Before the Civil War a group of people of color found their way to Fayette County. Trinity Christian College history professor, David Broadnax Sr says with the assistance of a white minister, they bought their own land.

DAVID BRODNAX SR: These Black farmers, they left their white neighbors alone and their white neighbors eventually left them alone.

AMY MAYER: Broadnax says after the so-called Fayette Mulattos; many of them were of mixed race, other African Americans came to Iowa and other Midwest states. He says some 19th century black families saw owning land but not final step toward economic freedom.

DAVID BRODNAX SR: You get yourself some land, and then you send your kids to school, and then you have even more economic power. So in that sense, you don't necessarily need to hold onto that land.

AMY MAYER: Other scholars have posited that in the upper Midwest and plains states, black families leveraged land for a couple of generations to catapult themselves into comfortable lives in more urban areas. But Valerie Grim, an Indiana University professor of African American and African Diaspora studies says that may be the case for some, but...

VALERIE GRIM: But that's not my experience in talking to black landowners at all, it was always property that you kept to protect your family.

AMY MAYER: So there would always be a home to return to. Meanwhile Grim says agriculture in the 20th century threw many hurdles up for African Americans - seed dealers who wouldn't sell to black farmers, black land grant university that didn't have adequate research money, and federal farm programs that denied loans to black farmers. By the early 21st century black farmers has won more than 2 billion dollars in settlements from discrimination cases against the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Grim says even more is needed, like a fund to help African American farmers get started.

VALERIE GRIM: It wouldn't make up for 400 years of domination, oppression and discrimination. But certainly it would increase the percentage of black farmers.

AMY MAYER: But in Fayette county Iowa there's another reason for the loss of black farmers, assimilation. Jeff Schimek identifies as white, but he's also a grandson of Addie Stepp of that pioneering black farm family. Schimek's generation grew up unaware of their African American lineage. He recalls speaking with another man, one who identifies as black, who also comes from one of those families.

JEFF SCHIMEK: He said, ‘Well, some members of the community just wanted to act as white as they could and assimilate into the whites as best they could,’ and he says, ‘Your grandad was that way,’”

AMY MAYER: Schimek and his cousin Brian Stepp say no one really talked about their mixed-race background when they were growing up. Brian Stepp worked on the farm with their grandfather for about 15 years.

BRIAN STEPP: "Brian, you put a thousand dollars into this place every year, and you’ll have something when I die." look where I am. I ain't have no thousand dollars every year.

AMY MAYER: Even though a Stepp descendant had kept farming, it wouldn't change the fact that in 2012 and 2017 the census of agriculture showed Fayette county had no self-identified black or African American farmers. But statewide the tiny number is growing, mostly in urban areas and many are recent immigrants. Brodnax, the historian, says farming isn't among the current calls for black economic empowerment.

DAVID BRODNAX SR: What I haven’t seen is that being addressed from a perspective of farming and land ownership. Not saying that no one has said that, but it definitely doesn’t seem to be a big part of the conversation in 2020.

AMY MAYER: But black restaurant owners, urban gardeners and local food activists are renewing conversations about who grows their food. All signs that African American interest in agriculture is growing which ultimately could bring about a new generation of black farmers in the Midwest. Amy Mayer, Harvest Public Media.

KAYTE YOUNG: Harvest Public Media is a Midwest reporting collective, covering food and farming stories throughout the heartland. This story is part of a series on black farmers in the Midwest. Find more at HarvestPublicMedia.org.

(Music)

As promised, we're back at Sobremesa farm. Juan Carlos and Robert have an integrated approach to farming. No component of the farm works in isolation. For instance they've planted a pollinator zone near the road with native flowers attracting bees, insects and birds. The birds keep the cabbage moth caterpillars off the broccoli and kale. Systems work together. They keep chickens for eggs, but they also contribute manure, they scratch up the soil in the garden beds, and keep bugs under control.

JUAN CARLOS: But the ones that are totally out, working and making noise, are the guineas.

KAYTE YOUNG: They also keep guinea hens.

JUAN CARLOS: Their main gift to us is they control ticks. We used to have so many here, now we have less because of them.

They wander. They can't really be contained. They are free spirits, I'd say...they even go to the neighbors, and we have to try and bring them back.

KAYTE YOUNG: But then do they come in at night, for shelter?

ROBERT FREW: We did train them to go into a coup. But essentially, their food and water they get here on the land as they're wandering around, eating a lot of ticks.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah, I would just think that predators are a problem if they're out in the wild, but maybe they've realized that it's good to come inside.

JUAN CARLOS: Yes, they know that. Last night, for example, I was busy emailing people about the market on Sunday, and it was already dark. They were calling, [as if to say] "Hey! Come, close the door!" So, after I closed the door, they were totally silent.

This is the house of the guineas and now it is time for them to come out. [chirping and squawking sound, guineas moving out of coop]

KAYTE YOUNG: The guineas are black with white speckles, they're larger than chickens, with almond-shaped bodies and tiny heads colored bluish white and red. They are quite striking.\

As we walked around the farm, I notice the guineas in the tall grasses, stretching their necks to the top of the stalks

JUAN CARLOS: Can! Chicky-chicky-chicky, look--ticks love to be on top of the grass.

KAYTE YOUNG: So that's what they're eating, they're not eating the seeds?

JUAN CARLOS: No.

KAYTE YOUNG: Oh, that's great.

KAYTE YOUNG: I noticed one of the birds making a lot of noise on top of a covered bale of straw.

[very loud guinea squawking]

JUAN CARLOS: They like to go to a high spot and tell the others that everything is fine. So after that, he will go there, and another one will come here, [and alert the others].

KAYTE YOUNG: [laughs] That's amazing! They're really cool looking.

JUAN CARLOS: Oh, I love them. They're noisy, they are, but they're so fun to watch--the way they run,

they play, just like kids!

KAYTE YOUNG: They do?

JUAN CARLOS: Oh, yes! They chase each other, you think they are going to kill each other. They get very close, and then the one chasing goes back, and then the other one goes again and [seems to say] "hey, no, come follow me again, chase me again!" They could go on and on and on.

And their babies are so cute, have you seen their babies?

KAYTE YOUNG: No, I don't think so.

JUAN CARLOS: Yeah, they look like a little chipmunk.

KAYTE YOUNG: So you say you don't eat the animals but do you eat eggs?

JUAN CARLOS: Oh yes.

KAYTE YOUNG: And what about the guineas, do they lay eggs?

JUAN CARLOS: Yes they do, they have a short period, they start end of April to September, that's it. We collect the eggs, and we sell them at the market. They're really rich.

KAYTE YOUNG: Are they smaller?

JUAN CARLOS: Yes, they are smaller, but in comparison with a chicken egg, they have a bigger yolk, not much of the white, so for baking, they are great.

Kayte[narrating]: Juan Carlos says the guinea eggshells are hard as a rock, and light brown in color. We have photos of the guineas and a few other snapshots from Sobremesa farm on our website, so be sure to check it out EarthEats.org.

Sobremesa has continued growing and selling food throughout the pandemic, with a few changes to their model to keep everyone safe. Juan Carlos shares stunning photography from around the farm on Instagram. You can find them at Sobremesa farm. We'll have the link our website EarthEats.org.

That's it for our show this week, I'm Kayte Young, thanks for listening. We'll see you next time, take care.

(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

RENEE REED: Get freshest food news each week, subscribe to the Earth Eats Digest. It's a weekly note packed with food notes and recipes, right in your inbox. Go to EarthEats.org to signup.

The Earth Eats team includes Eobon Binder, Mark Chilla, Abraham Hill, Taylor Killough, Josephine McRobbie, the IU Food Institute, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed. Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from the artist at Universal Productions Music. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey.