Y: Megachile pluto, commonly called “Wallace’s giant bee” is the world’s largest bee. And perhaps its most elusive. From 1981 to 2018 there were no reported sightings of it.

D: Wallace’s giant bee is the namesake of the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, who first collected the bee in 1858. That specimen resides at Oxford. For over a century, it was the only proof of the bee’s existence.

Y: Then, in 1981, an entomologist found the giant bee in the North Moluccas, Indonesia, where locals call it “Raja Ofu,” which means “king bee.” That sighting was never caught on film.

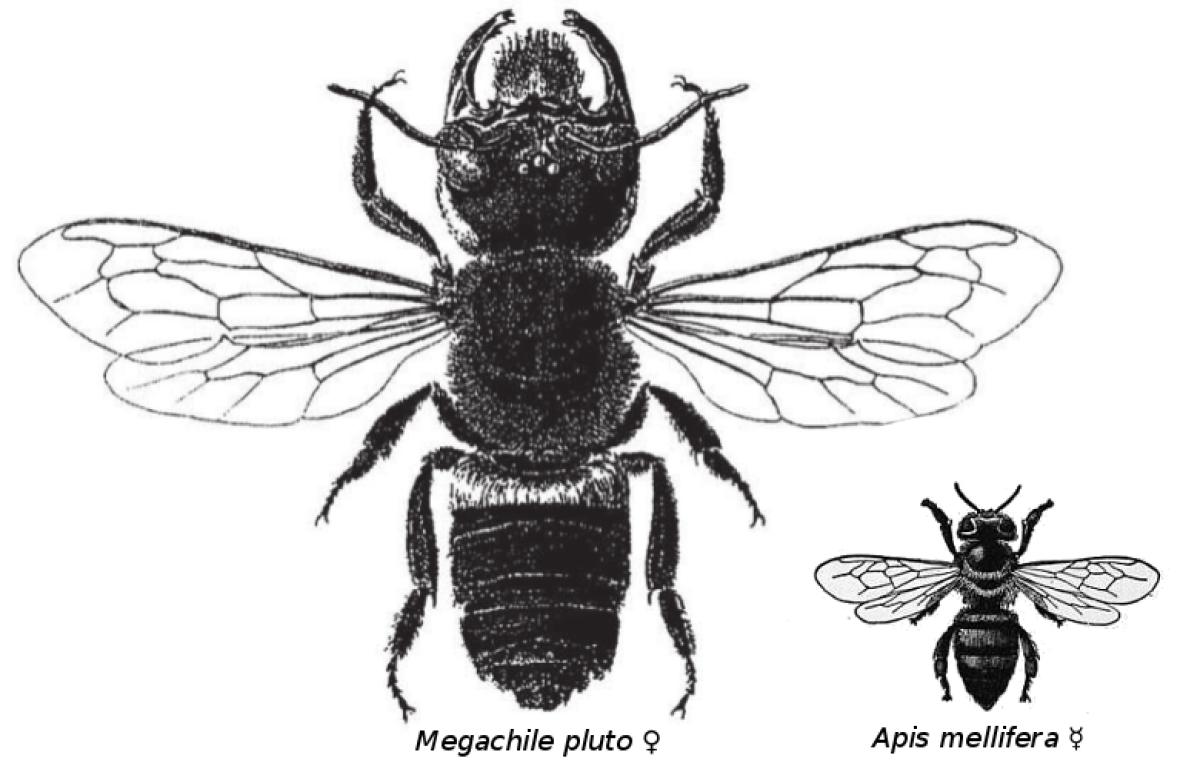

D: Thirty-seven years later, in 2018, scientists and a photographer located and recorded the bee living in the wild. The giant bee is a formidable sight: growing up to an inch and half long, with a wingspan of up to two and a half inches, plus large mandibles like a stag beetle.

Y: The bees use their mandibles to scrape sticky resin from trees in lowland forests. They use the resin to build compartments within tree-dwelling termite nests, where female bees raise young.

D: Much of that natural habitat has been cleared for local agriculture, and may soon be used to grow oil palm. Deforestation makes it difficult for scientists to find more specimens and study them, which they need to do in order to establish its need for protection under international trade agreements.

Y: Wallace’s giant bee is not currently protected, but there are currently surveys underway by the Indonesian Science Ministry to find more nests in hopes of protecting the species.