Video games count as therapy, right?

I have always enjoyed simulation games, especially ones like "Animal Crossing." Something about running around your own tiny island, filling it up with stuff and making friends with animal villagers (with admittedly redundant dialogue) brings me a sense of peace. This is my island, and I can decorate it however I want. Don’t even get me started on games like “The Sims,” where the options for customization and life outcomes are basically endless.

I’ve always wondered if Animal Crossing or other simulation games could benefit mental health. I find that the personalization that goes into these games is therapeutic. I don’t seriously believe that a game about collecting items and talking to avatars could really improve something like compulsive hoarding disorder or social anxiety, but maybe I’m wrong. Scientists have taken an interest in interactive virtual worlds to help people with certain conditions like these to improve their lives.

Many conditions, like obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), compulsive hoarding, and phobias, are treated with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and exposure therapy. This can be a daunting challenge because the patient must be willing to repeatedly expose themselves to their triggers to learn how to become less sensitive to them. Challenging these behaviors is like rewiring the brain, which is no simple task. For example, a hoarder might become anxious at the thought of being asked to throw personal items away.

What if you could simulate that experience to practice?

Fig 1. A tour of my house in Animal Crossing, provided for scientific analysis

A pilot study published in the Frontiers in Public Health journal asks whether virtual reality (VR) combined with inference-based therapy (IBT) can help patients combat these fears. IBT differs from standard CBT because it doesn't view obsessive thoughts as random intrusions, but rather a symptom of faulty reasoning. The idea in IBT is to help patients recognize the patterns behind these thoughts and understand the motivations behind them. Each participant in the study received 24 group sessions of IBT before moving on to the independent VR experience.

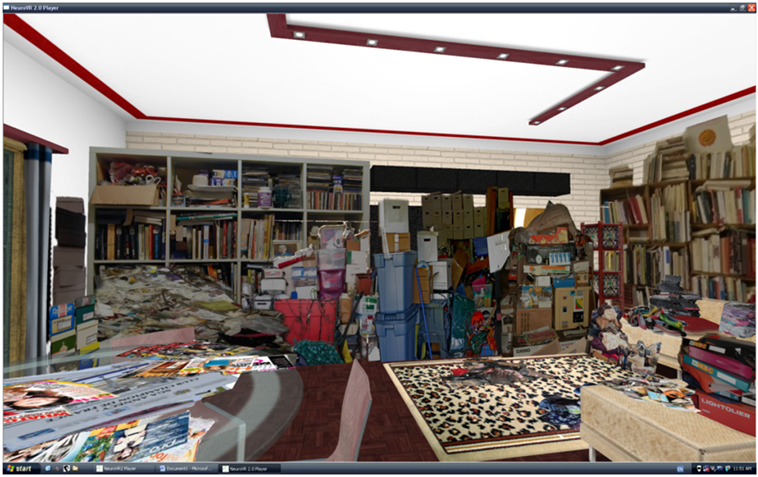

Researchers made customized virtual homes using pictures from participants' actual homes. They also collected a set of images of each participan's belongings. The first VR session let them become familiar with the virtual home and change its appearance to resemble their actual home. The second session focused on making a plan to sort through their different items. The last three sessions were used to begin discarding items into a virtual trash can, based on the subjective discomfort of each item.

The results suggest that virtual simulation of the participants' cluttered homes gave them a feeling of presence, despite being a non-immersive VR experience. For the experimental group, this also helped them develop a sense of action. But for the control group (who sorted through generic virtual items), their clutter at home actually increased. Both groups experienced anxiety during the VR sessions, but it seems the experimental group got a better sense of agency from sorting through their virtual belongings in their virtual homes, leading to less clutter at home following the study.

Living room of the control environment (St-Pierre-Delorme and O’Connor, Frontiers in Public Health)

Keep in mind that while this study explored VR, it didn’t involve using a headset. The results may have been different if it had used a fully immersive environment.

A lot of research shows that using a VR headset for exposure-based therapy could be effective, especially for people with phobias: like fear of heights, fear of flying, agoraphobia and panic disorder. You might think that in vivo (real-life) exposure therapy would be the most effective treatment; but surprisingly, studies involving virtual exposure to these phobias have been comparably effective in reducing avoidance behaviors. Additionally, headset VR has been used to distract patients with dental phobia during procedures.

For anxiety disorders, such as social anxiety disorder (SAD), the results of the VR studies are mixed. In one study published in the Behaviour Research and Therapy journal, participants with SAD were exposed to a variety of simulated social situations, such as talking to a stranger, being interviewed, or giving a talk in front of a crowd. A therapist controls the dialogue and tone of voice, the avatar’s appearance and style, and the topic’s degree of personal relevance. While virtual exposure was effective in reducing anxiety in both disorders, it wasn’t quite as effective as in vivo exposure to situations of the same nature.

VR exposure therapy is promising for treating phobias and anxiety; it also could help with people with substance use disorders (SUDs). Another type of exposure therapy used in treating patients with SUDs is cue exposure therapy. With this type of therapy, patients are exposed to the cues that would give them a craving, and then they are exposed to negative consequences they would have faced had they acted on that craving, to help re-condition them to avoid remission. Studies have shown that exposure to virtual stimulus of craving even has the same effect on the brain.

A new pilot study from Indiana University takes a different approach to substance-use disorder remediation, using a narrative-driven VR experience. The program is designed as a series of virtual interventions that you have with two future versions of yourself. The avatars are meant to look and talk like you, with age progression and signs of their condition.

They created avatars using high resolution photos of each participant’s face and full body and even recreated their voices. The layout of the physical space had a park bench, which was also modeled in the game. So, the participant could sit on a real bench that was also in-game. It seems kind of funny to listen to a virtual version of yourself talking while seated on a virtual bench that’s also in the real world.

![]()

Image of avatar rendering, (Brandon G. Oberlin, Springer Nature)

Beginning in a white room “beyond time and space”, participants met with their present self-avatar, who named loved ones, favorite hobbies and motivations to recover – then they produced two crystal balls and asked the participant to choose a future. 15 years into the future, to be exact. This was an illusion of choice, however. Staring into either crystal for 2 seconds caused the scene to fade into white before transforming the environment to a public park, accentuated by sounds of wind, lawn mowers, and even the smell of freshly cut grass using a custom scent diffuser.

They were now facing a future self – but they didn’t look too great. This avatar didn’t smile or make very much eye contact, was fidgety and had poor posture. This avatar recounted the negative consequences of continual substance use and shared regrets of not making choices towards recovery. These dialogues were also informed by interviews about the participants’ experiences.

After a brief transition back into the white room, the participants chose another crystal ball and were transferred back to the park. Only this time, a different future self was there, and they looked much happier. They maintained eye contact while speaking, smiled, appeared calm and had a better complexion and posture. This avatar reflected success and thanked the participants for working hard on recovery.

The trial also featured a text message system that sent virtual selfies from the positive future self for 30 days. Eighty-six percent of participants remained abstinent in the following 30 days.

“It was a really powerful experience… seeing myself older with a dirty shirt… I don't want to be that guy in 15 years. I would love to have a copy of the video of my selves talking to me. I want to be able to hold onto this. If I am feeling weak in my recovery, I want to be able to just pull it up on my phone and watch it. Having a virtual representation of the future is helpful because in recovery, we live in the present, so we don't know what the future holds—my life is the same now as it was then, and I don't have much to show for it. If I stay on the path, I can see the life I envisioned for myself. ”

-Participant 0027

So, VR has a lot of applications in mental health – from exposure therapy to motivational therapy experiences. This is still a new area of research, but it is already showing promise as a complementary tool for cognitive behavioral therapy. In the case of plausibility of these virtual worlds, it makes me wonder: Could more realistic graphics improve the effectiveness of these programs? I’ll let you know after I play “InZoi,” the new hyper-realistic Sims competitor, for a couple weeks.

Further Reading

- Startup supports addiction recovery through VR therapy using ‘future-self avatars’ : IU News

- Researcher explores use of VR to help older adults with Alzheimer’s stay independent : IU News

Learn more from the podcast

- Humans Behave Differently In Virtual Reality

- Do Violent Video Games Change Our Brains?

- A rattlesnake's rattling trick (VR experiment)

Sources

Shen, Y. I., Nelson, A. J., & Oberlin, B. G. (2022, September 15). Virtual reality intervention effects on future self-continuity and delayed reward preference in substance use disorder recovery: Pilot study results - discover mental health. SpringerLink. Deed - Attribution 4.0 International - Creative Commons

St-Pierre-Delorme, M.-E., & O’Connor, K. (2016b, July 19). Using virtual reality in the inference-based treatment of compulsive hoarding. Frontiers. Deed - Attribution 4.0 International - Creative Commons

Emmelkamp, P. M. G., & Meyerbröker, K. (2021, May 7). Virtual reality therapy in mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology.