In the late 1950s and the mid-1960s trumpeter Miles Davis led what are sometimes referred to as the "two great quintets"-the first featuring saxophonist John Coltrane, the second including saxophonist Wayne Shorter, pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Tony Williams. In the years between these two quintets, Davis employed half a dozen saxophonists, attempted a followup to his previous masterpieces with arranger Gil Evans, and battled increasing physical difficulties. On this edition of Night Lights we explore the music of those years as Davis evolved towards the second great quintet.

A Driven, Hardbop Groove

As the 1960s began, Davis found himself in a period of transition. Saxophonists John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley and pianist Bill Evans, key members of the group who'd made the landmark album Kind Of Blue, had moved on. Davis was flourishing financially, having purchased a five-story townhouse in Manhattan, and he had recently married dancer Frances Taylor, who appeared, at Davis' insistence, on the cover for his new LP Someday My Prince Will Come. He was the subject of an admiring profile in Ebony Magazine, titled "Miles Davis: Evil Genius of Jazz," and Esquire had included him in their round-up of "Best-Dressed Men." Most importantly, for fifteen years Davis had often been at the forefront of evolving trends in jazz--playing with bebop progenitor Charlie Parker in the mid-1940s, taking charge of the influential Birth of the Cool sessions, laying down notable hardbop sides in the early-to-mid 1950s, creating a series of orchestral jazz masterpieces with arranger Gil Evans, and leading the movement towards modal jazz, in which scales rather than chords were used to create solos and harmonic frameworks, with both Kind Of Blue and its predecessor, Milestones.

But challenges were on the horizon for Davis, as he confronted health problems, the death of his father in 1962, and the influence of a jazz movement that he hadn't led and didn't care for-the avant-garde. He was also a proud black artist operating in the racism-laden world of early 1960s America, with all of the frustations, indignities, and hazards that that entailed, including a beating that he'd received at the hands of a policeman outside New York City's Birdland nightclub in 1959.

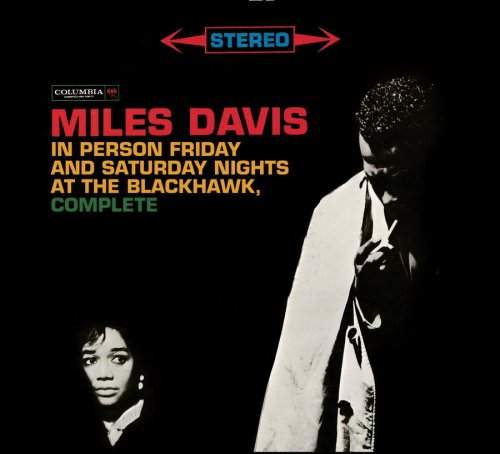

Davis began this era with his rhythm section still relatively intact, with Wynton Kelly on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and Jimmy Cobb on drums. In this three-year stretch Davis would employ half a dozen saxophonists, including hardbop stalwart Hank Mobley, sometimes called the "middleweight" champion of the tenor sax, with his self-labeled "round sound" and laidback, nuanced rhythm that was quite a change from the incandescent approach of John Coltrane. While Davis would ultimately find Mobley's style unsatisfying, it meshed well with the driven, hardbop groove of the 1961 rhythm section, caught notably on a weekend's worth of recordings made at the Blackhawk nightclub in San Francisco that spring.

Teaming Up With Gil Evans Again

The following month Davis played an unusual concert at New York City's Carnegie Hall, featuring his group and an orchestra led by Gil Evans, the arranger who'd teamed up with Miles to produce the classic albums Miles Ahead, Porgy and Bess, and Sketches Of Spain. The two had been good friends since the late 1940s, when they'd also helped usher the influential Birth Of The Cool sessions into being, and they would soon attempt a followup to their critically-acclaimed Columbia LPs. At the concert Davis sometimes played with just his group, just Evans' orchestra, or, in several instances, both ensembles.

The concert was a benefit for the African Research Foundation, formed in the late 1950s by doctors who wanted to get medical supplies and help to hard-to-reach locations in the emerging post-colonial areas of Africa. Drummer Max Roach, who had become involved in political activism, was skeptical of the foundation's ideological intent and invaded the stage during the concert with several other demonstrators, holding up placards in protest. Davis, upset, left the stage and came back after security personnel removed Roach and the other demonstrators. Columbia producer Teo Macero clandestinely recorded the concert, yielding, among other things, Miles performing a new Gil Evans arrangement that otherwise went unrecorded of Rodgers and Hart's "Spring Is Here."

"All I Am Is A Trumpet Player"

Not long after the concert a report appeared in DownBeat that the 35-year-old Davis was considering retiring. He told a jazz reporter at the Blackhawk that he had enough money coming in regularly to do so, and that he would pursue his musical pleasure simply through "buying records." The retirement didn't come to pass, but Davis' offhand remark was an indication of his state of mind. He'd been experiencing increasing physical pain and had found out that it was a symptom of having sickle-cell anemia. He was resentful of the image that he had in much of the press, telling Alex Haley in a 1962 interview for Playboy,

Why is it that people just have to have so much to say about me? It bugs me because I'm not that important. Some critic that didn't have nothing else to do started this crap about I don't announce numbers, I don't look at the audience, I don't bow or talk to people, I walk off the stage, and all that. Look, man, all I am is a trumpet player. I only can do one thing-play my horn-and that's what's at the bottom of the whole mess. I ain't no entertainer, and ain't trying to be one. I am one thing, a musician. Most of what's said about me is lies in the first place. Everything I do, I got a reason.

In the midst of all of this, Columbia Records was eager for Davis and Gil Evans to do another album together. Bossa nova was all the rage in 1962, and Davis and Evans began a project that would incorporate the new musical trend, only to see it fizzle out from lack of inspiration. Columbia, however, put out what they did record, a little more than half an LP worth of material, padding it with a later small-group session, and called the record Quiet Nights. Davis was furious and all but ceased to produce new studio recordings for the next two years.

"They Need To Have Some More Coffee"

Around the same time as Quiet Nights Davis made several sides with a piano-less ensemble that included a saxophonist he had already tried to lure away from Art Blakey, and one that would figure prominently in his eventual second great quintet: Wayne Shorter. Shorter remained with Blakey for the time being, though, and so Davis continued his hunt for a saxophonist in the wake of his numerous Coltrane replacements, among them Hank Mobley, Jimmy Heath, Sonny Stitt, Rocky Boyd, and even for a time, Sonny Rollins, newly-returned from his sabbatical. Trombonist J.J. Johnson, who'd played but not recorded with Davis' group in 1962, had also departed, and then at the end of the year Davis' longstanding rhythm section of Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers, and Jimmy Cobb quit.

There were aesthetic challenges as well. Throughout his career Davis had been an avatar of change in jazz, but in the early 1960s he was initially dismissive of the playing of free-jazz musicians such as Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor, remarking of Coleman that "he sounds as if he's all screwed up on the inside" and telling a DownBeat writer who was playing him a Taylor record, "Take it off! If that's what the critics are digging, they need to have some more coffee."

Despite his musical stasis and the pain he was experiencing from having sickle-cell anemia, Davis maintained an active day-to-day life. Alex Haley's September 1962 Playboy interview described the trumpeter's

restless daily home routine, asking questions at propitious moments while he worked out in his basement gymnasium, made veal chops Italian style for his family, took telephone calls from fellow musicians, his lawyer and stockbroker, gave boxing lessons to his three sons, watched TV, plucked out beginner's chords on a guitar and, of course, blew one of his two Martin trumpets, running up and down the chromatic scale with searing speed.

A New Group Comes Together

Out on the West Coast, Davis played a few gigs with a new group that included several jazz musicians from Memphis who'd made names for themselves on the Chicago scene-pianist Harold Mabern and saxophonists Frank Strozier and George Coleman. He also found a new bassist, Ron Carter, and ultimately made some recordings that dropped Mabern and Strozier and brought in a British pianist, Victor Feldman, who contributed a couple of compositions as well.

Still, Davis was not completely happy with the subsequent recordings, and it was only when he was back in New York that he finally hit upon the combination of musicians that would put him on the path to the second great quintet, adding a young pianist, Herbie Hancock, and an even younger drummer, 17-year-old Tony Williams. With the new lineup of Coleman on tenor sax, Hancock on piano, Carter on bass, and Williams on drums, Davis said that "for the first time in a while I found myself feeling excited inside."

Davis was on his musical way again, and would continue to pick up artistic momentum over the next year that would accelerate even more when George Coleman left and was replaced by the man Davis had sought out years earlier: Wayne Shorter. Before Coleman left, though, he made his musical mark with Davis through a series of outstanding concert performances, and we close this edition of Night Lights with the 1963 ensemble in such a setting, performing "Joshua."

More Miles

- A previous Night Lights show: A Brief Convergence: Miles Davis and Sam Rivers in 1964

Listen to Miles Davis' final studio recording with John Coltrane, made in the spring of 1961: