Gil Evans, a Canadian-born pianist and composer, is best known to jazz fans for his late-1940s and 1950s collaborations with Miles Davis that yielded classics such as Miles Ahead.

Although he seemed to spend much of the 1960s lying low, he made two of his finest records - Out of the Cool and The Individualism of Gil Evans - attempted several more projects with Davis, and helped craft albums for guitarist Kenny Burrell and singer Astrud Gilberto. We'll hear music from all of these sessions, as well as a track from Evans' end-of-decade LP Blues in Orbit.

Evans "enormously expanded the vocabulary of the jazz orchestra," as writer Gene Lees pointed out, reducing the standard big-band instrumentation, restraining its vibrato, and adding flutes, oboes, English and French horns and tubas.

Self-taught as an arranger, he created a quietly dramatic, dark-hued sound-world that drew on a multiplicity of influences ranging from Spanish music and the French Impressionists to Duke Ellington and the bebop revolutionaries of the 1940s.

Miles Davis once said of Evans, "He used to just go inside of music and pull things out another person normally wouldn't have heard."

Back To Cool

In mid-1960 Evans had just finished working with Davis on the LP Sketches of Spain. After a recording contract with Davis' label, Columbia, fell through, Evans did a six-week gig at the Jazz Gallery in New York's Greenwich Village - a converted theater that earlier in the year had played host to the leader debut of John Coltrane.

It was the first time that Evans had had an engagement as a bandleader in more than 20 years, and when it was over he took the group into the studio and recorded the album Out of the Cool.

The title invoked the famous 1949-1950 Capitol Birth of the Cool recordings that Evans had participated in with Davis, Gerry Mulligan, and other young musicians. They met regularly to discuss music in Evans' basement apartment - and it was perhaps a reference to Evans' earlier work with the Claude Thornhill big band as well.

Evans biographer Stephanie Crease sees Out of the Cool as a stylistic evolution for the arranger, citing the "floating quality" of the rhythm section and a more adventurous integration of improvised and written material.

More With Miles

in 1961 Miles Davis' quintet performed with a large ensemble led by Evans at Carnegie Hall.

Columbia Records wanted the two to collaborate again, and with bossa-nova jazz suddenly enjoying success, Davis and Evans went into the studio in 1962 to record a project that a Columbia memo described as "a Latin-American album with large dance band." But the results were fragmentary and unsatisfying to both artists, who felt that the music lacked the spark of their earlier efforts.

The subsequent 27-minute LP that Columbia Records released as Quiet Nights angered them. Evans tell Downbeat that "it was just half an album" and Davis refused to make any more studio recordings for his label until 1965.

Though Davis and Evans never successfully completed another extended recording, they remained in touch. Evans made generally uncredited contributions to what's known as the Second Great Miles Davis Quintet - the 1965-68 group that included Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams. We'll hear their last studio collaboration, "Falling Water," as well as "Wait Till You See Her" from the early-1960s Quiet Nights sessions.

A Pinnacle As A Leader

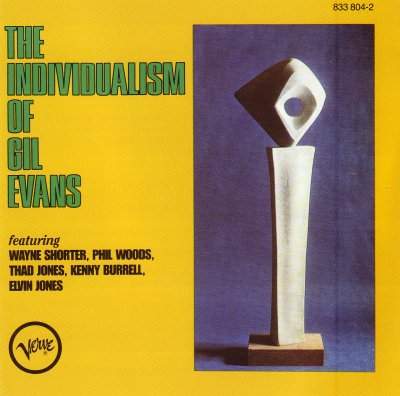

In 1964 Evans recorded an album that some critics rank with Out of the Cool as his finest leader date. The Individualism of Gil Evans was nominated for a Grammy, and it also marked a change in Evans' writing; as jazz critic Max Harrison said,

No longer is Evans concerned with mathematical symmetry or balanced repetition, but rather with a reflection of the mysterious complexity of the forms of nature…the music is a seamless web in which lines cross and re-cross, glowing, opalescent colors come and go in inexhaustible combinations…on these later recordings identification between the music and the individual performers is so complete that it is impossible to guess where writing stops and improvisation begins.

The album included tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter, a then-current member of Miles Davis' new quintet. We'll hear him featured on the Kurt Weill-Bertolt Brecht composition that Evans arranged for the album, "The Barbara Song."

No Pops, But A Singer And A Guitarist Instead

In the 1960s Evans nearly collaborated with another legendary trumpeter, Louis Armstrong.

The two met at a Grammy Awards reception. Evans learned that Armstrong was a big fan of the Davis-Evans LP Miles Ahead. Armstrong eventually exclaimed, "We could make an album! Now, I don't want to hear any of those funny chords of yours, but go see my man Joe Glaser." However, Glaser, Armstrong's manager, nixed the idea.

Instead, Evans would end up working with two other performers in the mid-1960s. One of them, singer Astrud Gilberto, had catapulted to fame through the hit "The Girl From Ipanema."

It was the first vocal album Evans had done in nearly 10 years. Gilberto later recalled their working together with great fondness, citing an aura about the arranger that combined musical wisdom, peace, and humility: "I would sit next to him at the piano, and he would ask, ‘See if you like this introduction,' or, ‘What do you think of these chords here?'"

Evans did the arrangements for another Grammy-nominated album around this time and became a breakthrough for its leader, guitarist Kenny Burrell. Burrell had worked with Evans on The Individualism of Gil Evans. He and producer Creed Taylor thought that Evans would be perfect for what they had in mind - a concept album featuring the guitar in a variety of musical settings.

Evans, a notoriously slow writer, took a long time to come up with the arrangements. Burrell, who called Evans a "master musical painter," said, "Hey, when it's done, it's going to be great. And it was."

Burrell also recalled Evans' meticulous work in the studio, blending his unorthodox combination of instruments, working with phrasing, and developing texture through volume control - all part of creating the Gil Evans "sound."

Into The Rock

Gil Evans would spend the rest of the 1960s working on several film scores, making a significant but uncredited contribution to Miles Davis' 1968 album Filles de Kilimanjaro, and helping to raise two new children with his wife Anita.

This edition of Night Lights closes with a composition that Evans had recorded previously with Davis in Hollywood in the fall of 1963. It was part of music for a play called Time of the Barracudas.

Tapes of the music were supposed to be incorporated into the play's live performances, but because of a dispute with the musicians' union, the music was never used, and the play itself was cut short because of clashes among its star performers.

The Evans-Davis version of the title track didn't come out until 33 years later.

In the meantime, Evans re-recorded it for his 1964 LP The Individualism of Gil Evans, and then again under the title of "General Assembly" for his 1969 album Blues in Orbit. By then both Evans and Davis were incorporating the influence of rock music into their work - Davis with his landmark Bitches Brew, while Blues in Orbit anticipated the direction that Evans would take in the 1970s, when he would pursue projects such as an album of Jimi Hendrix songs.

Watch Gil Evans with Miles Davis at the end of the 1950s: