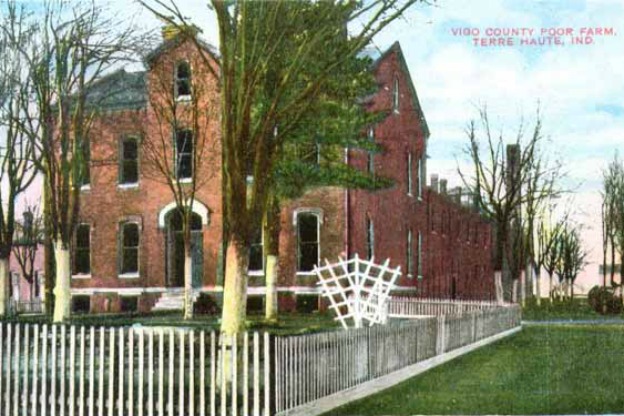

Vigo county's original poor home was built in 1853 on Poplar Street. The building pictured on the postcard was built in 1866 on a site on Maple Avenue between 19th Street and Fruitridge Avenue. In 1925, the home housed 61 men and 26 women. In 1936, this building was demolished and a new home built.

Indiana’s bygone network of asylums for the poor is an example of early governmental efforts to tackle poverty. Poorhouses—special farms or homes on county land set aside for the homeless poor—have existed from the beginning of Hoosier statehood.

In fact, the 1816 Constitution provided “one or more farms to be an asylum for those persons, who by reason of age, infirmity, or other misfortunes, may have a claim upon the aid and beneficence of society” (from Article IX, Section 4 of the Constitution of 1816). The hope in the early nineteenth century was that the people who had fallen on hard times and needed to live at the farm would not only find employment, but also “lose, by their usefulness, the degrading sense of dependence” that accompanied poverty.

[pullquote]The hope in the early nineteenth century was that the people who had fallen on hard times and needed to live at the farm would not only find employment, but also “lose, by their usefulness, the degrading sense of dependence” that accompanied poverty.[/pullquote]

The first law to establish an actual poorhouse was passed in 1821 and situated the institution in Knox County. Three “reputable citizens” were to be hired to provide accommodations, care, employment, and supervision to the adult residents—and to place the children in apprenticeships.

The new 1851 constitution authorized each county to purchase land for a poorhouse; just eight years later, in 1859, the General Assembly passed legislation authorizing counties to provide medical care for the poor. Each county’s commissioners administered a poor relief budget. They had a good deal of flexibility; around 1840, for example, commissioners in St. Joseph County provided funding for furniture for a poorhouse, food, firewood, coffins, medical care and medicine, shoes, hay, and even “cowbells for the cows kept for the benefit of the poor at the poor farm”.

Poorhouses were frequently located away from cities; although inspectors needed a place that was not too far to visit on a regular basis, it was also believed that cities exercised “potentially evil influences”. Poorhouses typically housed women separately from men, and they also provided homes for mentally ill citizens and for the elderly. Poorhouses often included functioning farms.

Poverty or “destitution” was usually not the sole reason given by those seeking admission; a number of factors brought people to the doors of the poorhouse, including sickness and age. Women and children were most often described as “orphan,” “homeless,” and “deserted”. Women who had left abusive relationships, were separated or divorced from their husbands, or had been abandoned often fell into poverty. Migrant workers—most often seasonal laborers who traveled for agricultural work—would stay in a poorhouse while they recovered from sickness or an injury or looked for work.

[pullquote]Most people stayed at poorhouses for less than one year; in St. Joseph County, the average stay was sixty-four days, with the majority of people staying less than thirty days.[/pullquote]

Most people stayed at poorhouses for less than one year; in St. Joseph County, the average stay was sixty-four days, with the majority of people staying less than thirty days. Most of these residents left voluntarily—usually after they had found employment or had been taken in by relatives. The elderly were the most “permanent” residents of Indiana’s poor asylums, and the second most common means of leaving was death, an indication of the large numbers of seriously ill and elderly forced to rely on the poorhouse.

By any modern standard, nineteenth-century poorhouses would be unacceptable institutions. They stand in history, however, as an important first step by state and local governments toward caring for those who could not care for themselves.

IMH Source Article: Bruce Smith, “Poor Relief at the St. Joseph County Poor Asylum, 1877-1891,” Indiana Magazine of History 86, no. 2 (June 1990): 178-196.

A Moment of Indiana History is a production of WFIU Public Radio in partnership with the Indiana Public Broadcasting Stations. Research support comes from Indiana Magazine of History published by the Indiana University Department of History.