Quincy Jones, global maestro

Quincy Jones, who died on Sunday at the age of 91, helped shape and score the musical world and culture that we've all grown up in from the 1960s on. His life and achievements have been lauded admirably in the New York Times and Night Lights has explored his early jazz years, but what I present now is a prior tribute and literary artifact that led to something faintly akin to "My Dinner With Quincy."

In the summer of 2009 I received a request from Indiana University jazz studies head David Baker, who was nominating Jones for an honorary degree from IU. Part of that process required David to solicit several letters of support for the nominee, making the case for why they were worthy of the honor. David knew me through my radio work at WFHB and then at WFIU; I'd interviewed him numerous times and we'd often talked of our Indianapolis hometown, developing an affectionate and easygoing rapport, the kind that David developed with so many people about so many things. When he asked me to pen a recommendation for Quincy Jones, I felt both thrilled and decidedly unworthy. White guy from the heartland who loves jazz, so what? But David assured me that he valued my input and that I was a part of the university community that would be bestowing this honor. And he had asked a number of other people as well.

The nomination went forward, and the honorary degree was awarded to Jones the following May in 2010. Jones came out to Bloomington for several days and held court with David and others both publically and privately. Baker and Jones' friendship went back many decades, and Baker had played in Jones' touring dawn-of-the-1960s big band. I got to experience their camaraderie first-hand when Indiana University president Michael McRobbie (a passionate jazz lover himself, I must note, who was delighted about Jones' visit) presided over a swanky dinner for Jones in the Indiana Memorial Union's Federal Room. As one of the support-letter writers I was invited to the dinner, so I got over my renewed feelings of being a cultural gate-crasher, put on a suit for the occasion, and brought along my box set of Jones' big band recordings from the era in which David had been a member.

I still have the menu from that night ("First Course: Terrine of leeks and asparagu wrapped in a crepe with roasted pepper sauce.") along with some other paper mementos of Jones' time here, stored in the box set that I brought to his tribute dinner. The Federal Room's decor is Colonial Williamsburg, with a Midwestern formal-club vibe. There were plenty of other people in the room (about 60 in all) talking with Jones and expressing their appreciation throughout the evening; he was charming and gracious to them all, a hip man-about-the-parlor, as he was in so much of his music. I waited till there was a bit of a lull as the night went on, and also checked with David to see if he thought Jones would mind signing my box set. Such a collector fanboy moment, in retrospect, but my God, it was Quincy Jones! The man was a global icon. I'd encountered him first through his film and TV music and his production of Michael Jackson's blockbuster albums, all of the usual pop-culture suspects, and only as an adult learned of his jazz origins and developed an appreciation for that part of his career, although jazz remained his source music throughout his life. ( In 1985 he told a DownBeat interviewer, "I wouldn‘t trade the era I came up in for anything.") He was a messenger who got stuff done.

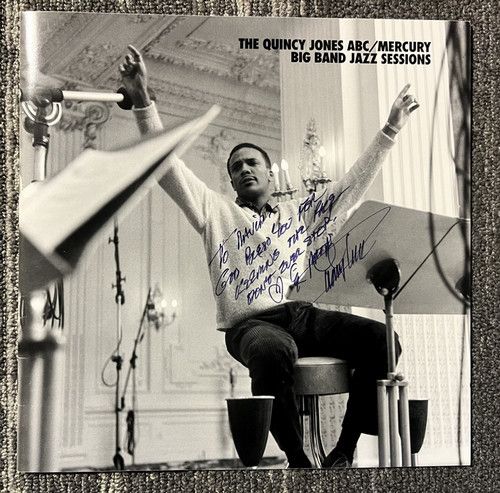

After getting David's OK ("Of course, man!"), I introduced myself and shook hands with Jones, who was sitting beside David. He was happy to hear that I was a jazz DJ and was delighted to see the Mosaic box set of his former big band. For the next few minutes he and David paged through the booklet, pointing to various musicians in the photos, remembering funny anecdotes about certain musicians' foibles and reflecting on their touring experiences while I stood there watching and listening. Jones eventually signed the front of the booklet (posted at the top of this page), and I've never quite been able to discern what part of it says, but I think it's: "To David, God bless you for keeping the faith. Don't ever stop."

Awe-inspiring as it is to spend any time in the company of a musical giant, or any figure of notable achievement, I don't think fleeting encounters like mine generally amount to much more than a comet's quick pass in terms of lasting personal significance, a fun "I met a celebrity!" story.... but Quincy Jones was more than a celebrity. He was an executive creative who helmed some of the most beloved and landmark musical recordings of the late 20th century. This is what I wrote when asked to make the case for Jones' honorary degree:

Dear members of the Honorary Degrees Committee,

American popular music—that intoxicating brew of jazz, funk, rock and pop that moves our minds as well as our feet—is the soundtrack of our culture, and nobody has done more over the past five decades to shape the sound that fills our lives than Quincy Jones. In so doing he has fulfilled the prediction of legendary composer and bandleader Duke Ellington, who inscribed a photograph for Jones shortly before his death in 1974 with “To Q, who will de-categorize American music.” Winner of 27 Grammy Awards, he has spanned musical eras and styles from Lionel Hampton to hiphop, incorporating them all into a considerable legacy that is so influential and widespread that it can be easily overlooked or taken for granted. It should not be, particularly because it is a legacy that teaches us much about where we have been and where we might be going. Changes in music often precede social and cultural change, and Mr. Jones’ career is a testament to the power of change and the dynamic force of talent wedded to perseverance.

Mr. Jones found his musical calling at the age of 11, when he and some friends snuck into a recreation room near an Army base in search of snacks; he ended up sitting at a piano instead. “I touched that piano and every cell in my body said this is what you will do for the rest of your life,” he later recalled. Beginning as a trumpeter and arranger in the late 1940s, as the last glorious years of the big band era gave way to the revolutionary sounds of bebop, he demonstrated an expert command of both forms of jazz. By the early 1950s he was arranging and directing sessions for up-and-coming hardboppers Clifford Brown and Art Farmer. In the late 1950s and 60s he led his own big bands and collaborated with some of the greatest vocal artists of the times, including Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee, Dinah Washington, Ray Charles, Sarah Vaughan and Peggy Lee; at the same time he expanded his efforts into the fields of pop and film scoring, and became the first African-American major-label record industry executive. As a composer, he wrote jazz standards such as “Stockholm Sweetnin’” and “The Midnight Sun Will Never Set,’ as well as signature tunes and scores that served as themes for popular television shows and movies ranging from Sanford and Son, In the Heat of the Night and Austin Powers to Ironside and the groundbreaking mini-series Roots.

Combining innovative verve and a driven work ethic, Mr. Jones continued to excel in the last decades of the 20th century, in a music-business field that is notoriously susceptible to sudden shifts, fashions and fads. As a producer, he worked with Michael Jackson in the late 1970s and 1980s to craft albums such as Off the Wall, Thriller, and Bad that sold tens of millions of copies around the world, helping to make Mr. Jackson’s music a sort of cultural diplomacy in the waning years of the Cold War. He also served on behalf of numerous humanitarian causes, including his direction of the megastar “We Are the World” recording session that raised money to fight famine in Africa. In recent years his We Are the Future Project has given support and opportunity to children from troubled areas around the globe. As a mentor to many younger musicians and an entrepreneur who founded his own record label, Mr. Jones has further provided a model of success that retains enthusiasm and integrity as its base.

It takes an unusual talent to apprehend the various strands of American popular music and fuse them into a powerful sound that celebrates the richness and diversity of our culture. In that way, as well as in others, Mr. Jones has done much to advance the cause of racial integration, in a manner perhaps more deeply profound than the legislative and judicial changes enacted in the past 50 years. If the law instructs us that we should be together as a matter of abstract principle, Mr. Jones’ music joyously informs us that being together can be a natural and celebratory way of life. His work has nurtured the public and private spirit of Americans; song is food for the soul, and Mr. Jones has fed us well for 60 years. It is with unabashed gratitude and respect for his efforts that I recommend him for an Honorary Doctorate from Indiana University.

Sincerely,

David Brent Johnson

WFIU-Bloomington, IN

Post-script: Here's Quincy Jones in 1984 predicting the future of music distribution (from a Radio & Records Magazine interview, cited in Michaelangelo Matos' book Can't Slow Down: How 1984 Became Pop's Blockbuster Year):

Jones: With computers around now, it would be very easy to get musical profiles of people's likes and dislikes... Maybe using TV to make impulse buying more accessible to more people... the screen lists whatever you're listening to... You say "I like that" and look at the information on the screen. Then you hit one or two buttons that ask for your purchase selection and credit card number... something in that direction.

R & R: That would be a great way to chart sales electronically.

Jones: Right. And it could be possible in five years for you to have no inventory in your house. No records, tapes, anything. If you had access to a satellite, a code book/catalog, and a television set, you could punch up anything you wanted anytime... And you could really target the music because you don't always want to hear a whole album. So you're programming several hours of music from this vast catalog in the sky. That would be incredible. You'd have access to anything out there that's current and have an intelligent way to catalog it.