“This man almost single-handedly energized the scene in the 80s," pianist and former Messenger Mulgrew Miller said of Blakey in 2010. (Concord)

In 1954 Art Blakey, a thirty-four-year-old drummer who was making a live recording at New York City‘s Birdland with a group of younger musicians, said "I'm going to stay with the youngsters. When these get too old, I'm going to get some younger ones. It keeps the mind active." Blakey lived that creed for the next 36 years, and the musicians who passed through the ranks of the Jazz Messengers, from Lee Morgan and Wayne Shorter to Wynton Marsalis and Mulgrew Miller, could form a well-filled jazz hall of fame unto themselves. In the world of 21st century jazz, which has been shaped by the expanding formal jazz education network of the past few decades, we can look back to Art Blakey as the original jazz educator, whose legacy continues to reverberate through the musicians who played with him in his final years.

Art Blakey was born in Pittsburgh on October 11, 1919 and made his mark in the jazz world in the 1940s as a drummer first with Fletcher Henderson‘s big band and then Billy Eckstine‘s legendary bebop-oriented orchestra. In the late 1940s he led his own big band called The Messengers, but it proved economically unviable; in the meantime Blakey worked and recorded with some of the brightest lights of the bop generation, including Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, and Thelonious Monk. In the early 1950s he and pianist Horace Silver revived the Messengers project as a small group, and the 1954 recordings they made at Birdland have routinely shown up on greatest-jazz-albums-of-all-time lists ever since. They also helped popularize the hardbop movement, which incorporated blues and gospel influences, a driving beat, and a hotter soloing sound than some of the other jazz styles in vogue at the time. Blakey‘s Messengers thrived throughout the rest of the 1950s and the early 1960s, with two key elements already in place: a fairly regular turnover of young musicians every several years, and much of the band‘s book coming from the pens of those musicians. But Blakey endured a long stretch of diminished popularity from the mid-1960s to the end of the 1970s, as hardbop and acoustic jazz fell out of favor. At the dawn of the 1980s, the drummer brought a New Orleans trumpeter still in his teens into the Messengers, and things began to change. The trumpeter was Wynton Marsalis, and his arrival marked the beginning of what would prove to be a highly productive renaissance for Blakey in his final decade. Here‘s a 1981 edition of the Messengers with Marsalis on trumpet:

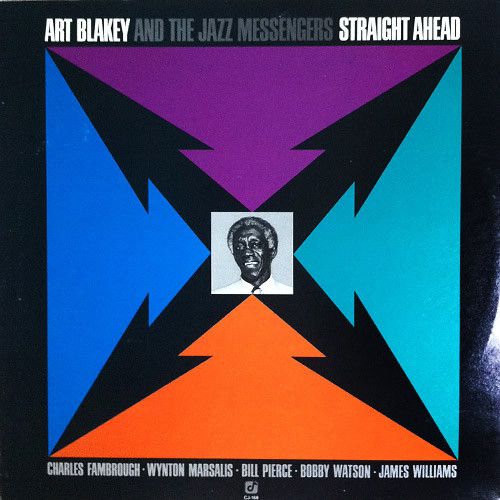

"Ms. B.C." appeared on Album Of The Year, which along with Straight Ahead, a live recording featuring the same band, received a glowing double review in DownBeat that heralded them as avatars of a hardbop acoustic-jazz renaissance. By then Wynton‘s older brother Branford had joined the band as well--a move he has always said came about because of Blakey‘s desire to keep Wynton in the group. Branford played alto sax as a Messenger, taking over Bobby Watson‘s spot. Though Wynton Marsalis is often given a great deal of credit for the Messengers‘ new life in the early 1980s, Bobby Watson had built the foundation for that revival during his 1977-81 tour of duty. Watson‘s compositions, like those of his Messenger predecessors, also stayed in the band‘s book. Here‘s one of them, from a live performance in January 1982 with both Marsalis brothers aboard:

Wynton and Branford Marsalis were just two of the so-called 1980s "young lions" for whom the Jazz Messengers served as a launching pad. By 1984 the group had turned over completely, with another young New Orleans trumpeter, Terence Blanchard, serving as the Messengers‘ new musical director. Filling Wynton Marsalis‘ shoes was another part of the Messenger‘s motivational tradition; as Blanchard later observed, "You knew who came in the band before you, so you didn‘t want anybody coming to the shows and saying, ‘Damn, he‘s sad.‘" Blanchard‘s four-year stint as a Messenger was one of the band‘s longest, and while he‘s commented that "that band aged me forty years," he‘s also repeatedly praised Blakey as a leader, teacher, and musician. He also tells the same stories to his side musicians now that Blakey repeated so often to Blanchard and his colleagues. Blanchard, a multiple Grammy winner who has scored numerous movies, including many of Spike Lee‘s films, is yet another 1980s Messenger carrying on the message in his own highly-successful manner. Here he is with the Jazz Messengers in 1984 featured on the ballad "Tenderly":

Blakey had just entered his sixties as the 1980s began, and he had to deal with an increasing deterioration in his hearing in ensuing years, often wearing a hearing aid off the bandstand. Onstage, "I play by vibrations," he told DownBeat writer Kevin Whitehead in 1988. Whatever challenges Blakey faced, he maintained the same style of leadership, both directly and indirectly. "I always felt I needed to direct the rhythm section," pianist and Messenger Mulgrew Miller said in another 1988 DownBeat article. "With my comping I thought I could pull the rhythm section along… but I quickly found out that you can‘t lead Art. I found that out FAST." Blakey said the Messengers always sounded like the Messengers because he was "directing the traffic" with his drumming. "Art played with you," bassist Charles Fambrough said in 2010. "He never ignored you, whether you were making it or not. That‘s what I loved about him: You could be in trouble and Art would come to your assistance and show you what to do." But Blakey also gave his sidemen a high degree of creative freedom, something that young Messengers such as Branford Marsalis would emulate in their future careers as leaders. And he continued the Messenger tradition of pushing his musicians to write material for the band. Here are the Messengers in 1985, performing pianist Mulgrew Miller‘s "Second Thoughts":

Blakey prided himself on never firing anyone, but he also prodded band members to move on when he felt the time was right, both for them and for the band. "This isn‘t the post office," he liked to say. By the fall of 1986 trumpeter Wallace Roney and alto saxophonist Kenny Garrett had replaced Blanchard and Harrison. "That was an institution, playing with Blakey," Garrett told Alan Goldsher in 2002 for the book Hardbop Academy. "He taught me how to play in a short amount of time because there were so many other horn players there and everybody needed a chance to express themselves… I learned a lot, some things about being a bandleader, what to do and some things not to do. That was a stepping-stone." Here are Art Blakey‘s Jazz Messengers in 1986 performing Kenny Garrett‘s "Feeling Good":

Art Blakey spent 36 years, or slightly more than half of his life, leading the Jazz Messengers. On October 16, 1990, just five days after his 71st birthday, he died of lung cancer. In 1976 he had told writer John Litweiler, "Respect is the most important thing in the world today, because that‘s the only thing that follows you to the grave. You never find an armored truck following a hearse." By that measure, and so many others, Blakey succeeded. "Definitely when Art Blakey passed he left a great void," pianist and former Messenger Mulgrew Miller told DownBeat Magazine in 2010, for an article aptly titled "A Leader‘s Long Legacy Lives On. "This man almost single-handedly energized the scene in the 80s. It started before Wynton, but because of his success--which was definitely due to his exposure as a Messenger--scores of young musicians came up hoping to play with Art and the Messengers." Blakey sometimes downplayed talk of himself as a teacher or the Jazz Messengers as a jazz "school" or "academy," but as jazz critic Gary Giddins wrote after Blakey‘s passing, "No one in any style of American music apprenticed more musicians who went on to bigger, if not always better, things. He was an advocate for musicians and a proselytizer to the general public. His devotion to jazz, his sermonlike effusions on its behalf, characterized the man as surely as his ability to drum audiences into a state of unembarrassed elation." Giddins‘ eulogy brings to mind Javon Jackson, a Messenger saxophonist in the late 1980s, recalling Blakey‘s command to the band just before a performance: "Swing them to death."

More Art Blakey On Night Lights:

Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers: Class Of '57