The 1960s is one of the most talked-about, argued-about, mythologized periods of American history. This edition of Night Lights highlights some women jazz artists who made records of note during that troubled and interesting time when women's rights was an issue at the forefront of American culture.

Women had always had a challenging road to travel in the world of jazz. For all of their progressive views regarding matters of race, jazz musicians tended to view women in a similar way to the rest of society. Women had made it as singers, they'd made it as pianists, and artists such as Mary Lou Williams and Melba Liston had succeeded as composers and arrangers, but the jazz scene remained dominated by men.

Reflections of Change

Many of the artists featured on this program got their start in the 1950s, but as the 1960s went on their music sometimes evolved in ways that reflected the artistic and cultural changes that were going on around them. Pianist and harpist Alice Coltrane was one such artist; she'd come out of Detroit as a bebop-influenced pianist, but after marrying John Coltrane, who eventually brought her into his group as a pianist and encouraged her to start playing the harp, her music began to move in a freer and more exploratory direction. She also became intensely involved in Eastern-based religions, and her changing spirituality was reflected in the music that she made after her husband's death in 1967.

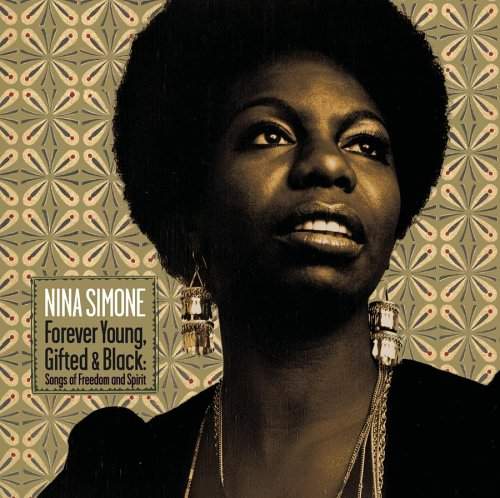

While Alice Coltrane's music involved explorations of the 1960s spirit, singer and pianist Nina Simone's music touched on the era's outspoken commitment to civil rights. Simone's music brooked no boundaries—she performed jazz, blues, pop, and R&B—and was dubbed "The High Priestess of Soul" for her fearless, assertive approach that could sound wary, proud, or full of mournful sensitivity. In some ways Nina Simone became as much an icon of the 1960s as Billie Holiday did of the 1930s and 40s. "To really understand the 60s," fellow singer Abbey Lincoln said many years later, "you had to hear Nina." We'll hear two performances by Nina Simone: "See Line Woman," the lyrics of which were suggested to her by her friend, the poet Langston Hughes (who would also join her in co-writing the civil-rights piece "Backlash Blues"), and "Young, Gifted and Black," which she co-wrote with Weldon Irvine for her friend Lorraine Hansberry, the playwright of "A Raisin In the Sun" who had passed away in 1965 at the age of 35.

Playing And Composing

Like Nina Simone, Shirley Scott started out playing piano, and trumpet as well, but in 1955 at the request of a club-owner she switched to organ and rose to recognition on that instrument. Scott teamed up with tenor saxophonist Eddie Lockjaw Davis for a series of records on the Prestige label, and formed another relationship that proved to be both artistically and personally significant, with saxophonist Stanley Turrentine. Together Scott and Turrentine made some of the most notable soul-jazz records of the early 1960s. Fellow organist Jimmy McGriff praised her playing for its strength, which, to him, transcended gender:

Shirley would come up and play with her trio, wowing the crowds wherever she went. See, Shirley had a rough sound. A man's sound. But at the same time she had a woman's touch. She'd take her shoes off and just tear it up.

One woman artist who appeared in these years on just one LP, the epic double-album Jazz Composers Orchestra, but who made her mark throughout the decade as a composer, was pianist Carla Bley, whose music was recorded by George Russell, Jimmy Giuffre, and other leading figures of progressive jazz. After the 1960s, Bley would go on to make her own records and gain critical prominence; her 60s legacy and significance is primarily in others' recordings of her compositions.

Bley grew up in San Francisco playing music in a church setting, but in her teens she abandoned home and religion and made her way to New York City, where she worked as a cigarette girl at Birdland. There she met the pianist who would become her husband, Paul Bley. He became one of the most frequent interpreters of Carla Bley's music, which one writer has described as "hyper-modern jazz…asymmetrical compositional structures that subvert jazz formula to wonderful effect, with unpredictable melodies that are often as catchy as they are obscure."

Other Aspects

While Carla Bley was making a name for herself in outside-jazz circles, singer Nancy Wilson was achieving success in the jazz and popular-song mainstream, launched in large part by her 1961 collaboration with saxophonist Cannonball Adderley, who'd persuaded her to move to New York City after hearing her perform a couple of years earlier. Wilson went on to record more than 70 albums and win three Grammys; she was a seemingly-constant presence on the mid-1960s Billboard charts. Like Nina Simone, Wilson can't really be classified as simply a jazz singer; both Wilson's and Simone's music from this period remain vibrant reflections of the times—though Nancy Wilson's embodies a more jazz-cabaret, pop side of the Sixties.

Like Alice Coltrane, Dorothy Ashby came out of the great mid-20th century Detroit jazz scene. Though she entered that scene as a pianist, she was eventually able to find work for herself on her favored instrument, which she'd learned to play at Detroit's Cass Tech High School: the harp. It was not a common musical role to play in the jazz world but as Ashby would later say, "This isn't just a novelty, though that is what you expect. The harp has a clean jazz voice with a resonance and syncopation that turn familiar jazz phrasing inside out."

Ashby began to record in the late 1950s, and toured the country with a trio that included her husband John Ashby on drums. As the 1960s went on, her music began to reflect the influence of soul and world music as well as jazz, and decades later her records would find favor with hip hop artists looking for samples.

The Avant-Garde

Our Night Lights program closes with music from two underground artists from the 1960s. Singer Jeanne Lee, who was involved in the 1960s art scene, made an outstanding record early in the decade with pianist Ran Blake, and played a prominent role in Carla Bley's landmark 1971 jazz opera Escalator Over the Hill. We'll hear her team up with New Thing saxophonist Archie Shepp. We'll also hear a solo from trumpeter Barbara Donald, who was married in the 1960s to saxophonist Sonny Simmons. Donald could play bop and she could play outside; she was an integral part of Simmons' 1960s groups and remains an unsung heroine of the era. Despite her alliance with Simmons, Donald ran into resistance on the free-jazz scene. Years later, Simmons told writer Clifford Allen

I had a lot of problems with the cats in New York because of that. Here's this beautiful white lady standing on the bandstand in a mini-skirt with a black musician, which had never happened in the history of the music, and she was playing all this trumpet, and it kinda deflated cats' egos. They didn't like us too much.

More Women Jazz Artists on Night Lights