Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell emerged from the 1940s New York City jazz scene as leading lights of modern jazz piano, but they had a friend, a musical brother whose complex compositions and unique style made him a worthy contemporary, even though he never garnered the recognition that came to Powell and Monk. His name was Elmo Hope, and on this edition of Night Lights we'll hear him with Clifford Brown, Harold Land, Curtis Counce, and his wife and fellow pianist Bertha, as well as some recording dates that he made as a leader.

"Oblique, Vulnerable Beauty"

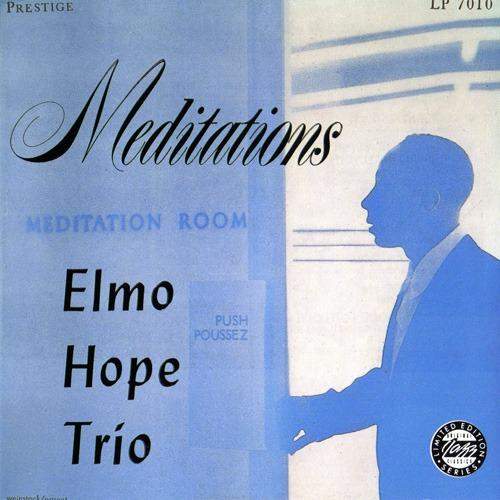

When pianist Elmo Hope's eponymous 1959 trio album was reissued in 1970, DownBeat jazz critic Larry Kart wrote, "Elmo Hope's conceptions were, for once, given their just expression. Music of such honesty and depth will always be rare, and its oblique, vulnerable beauty gives it a special place in the history of jazz." Kart was writing just three years after Hope's death at the age of 43, but even today Hope's place, well-earned, remains primarily in the shadow of his compatriots and friends, Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell.

Born in 1923, the son of Carribean immigrants, by the age of 14 Hope had already made a name for himself in Harlem, attending one of its best music schools and performing as a concert pianist. He was also beginning to compose jazz pieces as well and spending time with Bud Powell, another superlatively talented pianist just a year younger than Hope. But in 1940 he walked into an altercation in Harlem and ended up being shot in the back by a policeman. Though he recovered, Thelonious Monk biographer Robin D.G. Kelley says Hope was never the same after the incident. He continued his friendship with Powell and developed one with Monk as well, but in 1943 he enlisted in the army and was off the scene for several years. Upon his return he spent time with some R and B bands and resumed his camaraderie with Monk and Powell. Saxophonist Johnny Griffin jammed as a teenager with the three of them and recalled that they were like "triplets."

Avoiding Bop Cliches

Hope's first significant break came right around the time of his 30th birthday, when he was enlisted as a pianist for one of the first recording dates to spotlight the emerging sound of hardbop. It also gave listeners their introduction to Hope's evolving style, described by jazz writer David Rosenthal as full of "somber, internally shifting chords… punchy, twisting phrases…and smoldering intensity." Here's Hope with trumpeter Clifford Brown on Blue Note Records, doing "Carvin' The Rock," a tune co-written with Sonny Rollins with a title that alludes to Riker's Island, the prison where a number of New York City jazz musicians spent time on narcotics charges:

Hope's performance on this date led to a trio session under his own name for Blue Note just a week later and a further chance to showcase some of his compositions. In his hardbop book Cookin' writer Kenny Mathieson cites this date as proof of Hope's putting conceptual dimensions over pyrotechnic displays and notes that Hope's ideas "generally avoid bop clichés, and pursue a singular and usually unpredictable course through the material at hand, employing characteristic devices like asymmetric phrase lengths across the bar lines, unexpected intervals, and sudden percussive dissonances or unanticipated accents":

In the next several years Hope landed a wide array of recording dates with musicians such as Lou Donaldson, Sonny Rollins, Jackie McLean, and John Coltrane, making a couple of albums under his own name as well. But Hope, like numerous other musicians of the time, had fallen prey to heroin addiction, and his subsequent legal troubles resulted in the loss of his cabaret card, a New York City requirement for playing night clubs.

After going out on the road with trumpeter Chet Baker, Hope settled in Los Angeles in 1957, and found a musical helpmate and champion in saxophonist Harold Land, who used Hope on some of his own dates and brought him into Curtis Counce's West Coast hardbop quintet to replace pianist Carl Perkins after Perkins' death in 1958. "He had one of the quickest minds I ever witnessed in action," Land later recalled. "He could write great tunes just the way you or I would sit down and write a letter."

Go Back East, Young Man

The aesthetic success of Hope's late-1950s West Coast dates with Land led to a trio album that stands at the center of the pianist's artistic legacy. Jazz writer David Rosenthal wrote that "Elmo's compositions are dominated by a sense of urgent musical questing as well as by a feeling of self-exposure far beyond standard jazz postures… (his) solos do everything possible to convey these tonalities… Ideas and fragments of ideas abruptly spill over and intersect each other, as if the pianist's hands could barely keep pace with his emotions. Bars densely packed with runs and baroque filigrees alternate with stark, dissonant figures or Monkish seconds, wide intervallic leaps, and octaves…all these elements, taken together, create an effect of conventional forms being pushed to their limits under the pressure of Hope's turbulent sensibility." Reviewing the album in DownBeat, John Tynan called it "a revealing portrait of the pianist…Elmo Hope's inner story is in this album for anybody who will listen. And a moving story it is":

Despite the album's glowing review in DownBeat, Hope's prospects did not improve, and he found the laidback West Coast atmosphere somewhat stultifying. In a January 1961 DownBeat article titled "Bitter Hope" he praised little besides the weather and advised aspiring players to go to New York, "both for inspiration and brotherly love. They'll hear more things happening, and they'll find young musicians there, 14 and 15 years old, who make the musicians here look like clowns."

Still, Hope was in good health during his California sojourn and made the recordings for which he's best-known today. He also met Bertha Rosemond, the daughter of an actor and dancer who had entertained pianists such as Nat King Cole and Art Tatum in their home, inspiring Bertha to take up the instrument as well. She approached Hope one night at a Los Angeles club to tell him that she'd been studying his music; he didn't believe her until she invited him to come to her house to hear her play. The two eventually married, and in 1961 Hope returned to New York City, making an album for Riverside appropriately titled Homecoming! We'll hear one of the compositions he wrote for Bertha, "A Kiss For My Love," as well as a recording later that year that teamed him up with his wife, a two-piano take on the standard "Yesterdays":

"People Need To Know About Elmo"

Despite these recording dates, Hope soon found himself struggling to regain his professional footing in the New York City scene. He reconnected with Thelonious Monk and other musicians, sometimes conversing on a stoop close to Monk's apartment. One day the stoop collapsed and Hope, Monk, and saxophonist Tina Brooks all fell into a sinkhole. A journalist pestered Monk for quotes after the event, but all he would say was "Elmo Hope is the world's greatest pianist!" "People need to know about Elmo," he explained.

That didn't come to pass, though Hope made several more recordings, including the unique LP Sounds From Riker's Island, an album of mostly Hope compositions performed by the pianist, Philly Joe Jones, and other musicians who had spent time in New York City's notorious prison on drug charges. But the gigs dried up, and Hope also had difficulty keeping his addiction demons at bay. His last public performance and recording dates came in 1966, and when his friend and colleague Bud Powell died that summer at the age of 41, Hope was too distraught to attend the funeral.

Less than a year later, after battling pneumonia for several weeks, Hope died too, of a heart attack on May 19, 1967. He was 43 years old. Jazz critic Ira Gitler described a heartwrenching scene at the funeral home, with a recording of Hope's composition "Monique" playing over and over again "as a bittersweet reminder of of what a musician he was and what might have been. As the coffin was about to be closed, his aged father ran toward it sobbing ‘My son! My son!'" "Elmo died on May 19th," Gitler wrote, "but hope had been deceased for some time." But for those who care and know to listen, who can find his music in both its original incarnations and its new interpretations today, Hope lives:

An Elmo Hope Bibliography

- An Elmo Hope discography

- Kenny Mathieson's Cookin': Hard Bop And Soul Jazz 1954-1965 contains a good section about Hope

- Ditto for David Rosenthal's Hard Bop: Jazz And Black Music 1955-1965

- Robin D.G. Kelley's Thelonious Monk: The Life And Times Of An American Original and Peter Pullman's Wail: The Life Of Bud Powell include numerous references to their respective subjects' relationship with Hope

- Jazz Injustice: Genius In The Shadows (1987 New York Times article)

- A brief online biography

More Elmo Hope And Hardbop Piano On Night Lights

From Rehab (previous Night Lights program that includes more of the 1963 Hope album Sounds From Riker's Island)

- Clark's Last Leap: Sonny Clark 1961-62 (previous Night Lights program)

- Thelonious Monk: From Man To Myth (previous Night Lights program)

- Time Flies: The Life And Music Of Bud Powell, Part 1 (previous Night Lights program)

Night Lights program outtake: