In 1985 trumpeter Miles Davis left his longtime label Columbia Records, where he had recorded jazz masterpieces such as Kind Of Blue and Bitches Brew over the course of 30 years, for Warner Brothers and began what would prove to be his final run of recordings. Albums such as Tutu and Amandla found Davis working in a synthesizer-enhanced 1980s musical landscape, with bassist Marcus Miller emerging as a key new collaborator. We'll hear music from those albums as well as some live recordings and one of Davis' late-period sideman appearances on this edition of Night Lights, starting off with "Backyard Ritual" from Tutu, written for Davis by keyboardist and composer George Duke, who was surprised that Davis ended up using the demo that Duke sent him to play over for the album version of the track.

In 1985 Miles Davis was on the verge of turning 60, only several years returned from a half-decade long retirement, and he was unhappy with Columbia for several reasons. He felt the label wasn't supportive enough of a recent recording project that would eventually be released under the title Aura; he wanted more money; and he was bristling about the new favorite-son status Columbia had bestowed upon the young trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, who had made some less-than-favorable remarks about Davis' post-mid-1960s music to the jazz media.

At Warner Brothers Davis continued forging his 1980s sound that one writer has described as "chromatic funk," played on recordings by pop and R and B artists such as Chaka Khan, Cameo, and Scritti Politti, and made a studio album, Tutu, that some regard as a late-period masterpiece. Davis' initial recording sessions for Warner, however, went unreleased for many years, and still have not come out in their entirety; they're known as the "Rubber Band" sessions, eventually abandoned in favor of the album that would become Tutu, and they possess an even harder pop-funk sound than what Miles would generally end up pursuing in his final years.

"He Can Be The New Duke Ellington Of Our Time"

One of the most intriguing near-collaborations for Davis' Warner Brothers Years was with pop artist Prince, who was then at the peak of his commercial fame, still riding high on the album and movie Purple Rain, and writing prolifically for other artists as well as himself. Prince admired Davis and sent him a tape of a song, telling him that he trusted Davis to play whatever sounded right over it. Davis returned Prince's admiration, saying "For me, he can be the new Duke Ellington of our time, if he just keeps at it", a comment that outraged jazz critic Stanley Crouch, who lambasted Davis for his post-1960s musical maneuverings in the Village Voice and the New Republic, calling his 1980s incarnation "nothing more than a winged death's head floating on the hot air of insipid writers and gullible listeners" and attacking the trumpeter as "the most brilliant sellout in the history of jazz." Though a studio recording and live performance of Prince and Davis together have surfaced in recent years, and Prince songs sometimes showed up in Davis' concert sets, the two never did end up making an album together. Here's the Prince song with Davis playing trumpet that was originally intended for Tutu:

Prince and Miles Davis performing together at Paisley Park, New Year's Eve, 1987:

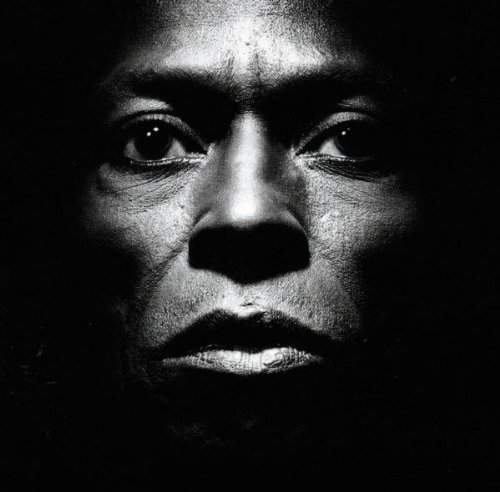

The most significant collaborator of Miles' late period proved to be Marcus Miller, a bassist and composer who had played with Davis in the early 1980s. He was suggested to Miles by Warner Brothers producer Tommy LiPuma. When Miller realized that Davis was open to working with drum machines, synthesizers, and other non-live-studio elements, he set out on the course that ultimately led to Tutu, writing and recording much of the music himself, with Davis then playing his trumpet parts over the results. Tutu, which also sported a dramatic black-and-white cover photograph of Davis' face, presented a musical landscape that sounded very much of its mid-1980s time, but which also struck some listeners as an updated version of what Davis had done with arranger Gil Evans in the late 1950s.

Tutu yielded a Grammy for Davis in the best jazz soloist category.

"Worth On The Terrain That It Sets Out To Conquer"

Davis' 45-year career on record has often been divided into stylistic periods: bebop, cool jazz, hardbop, modal, electric, and what Paul Tingen has labeled the "chromatic funk" of his 1980s comeback period. Davis was never content to stand still, and decades later, one can argue that his final period was his attempt to embrace pop stardom in his own way. He appeared in movies and on television shows such as "Miami Vice," made a Honda Scooter commercial, became more outgoing in his concert appearances—all of this amounting to an approach that was new for him. Musician Jim Sangrey, while acknowledging that some jazz fans might not find as much that they like in this period of Davis' career, says

I like the Warner Brothers period stuff well enough, but the live shows usually make for a more engaging "jazz" experience, although "jazz" is not really the point of any of this stuff in the first place, so I can see how if that's what you're looking for, you're not gonna be well-pleased, because it ain't really there, nor is it supposed to be.

What is there, I think (and this thought only strengthens as the distance grows larger) is Miles deciding that he's going to take on "pop" and win - on his own terms, with his own aesthetic, with his own representations. Now, some might call that "selling out", but I think you can make at least just as strong a case that it's an act of defiance. After all, the notion is that "pop" = stupid, shallow, and simplistic, and none of the WB-era music (especially in concert) is ever all that, especially texturally. Wasn't Miles always a texturalist? For that matter, wasn't Miles always about not "settling" for being ghetto-ized or pigeonholed, musically or personally?

I'm not saying that anybody who doesn't like it is wrong, because that would mean that you have no right to look for what you like/want/need in music, and there's no way I'd even begin to suggest that. I'm just saying that the music has worth on the terrain that it sets out to conquer.

Davis' Warner Brothers period continued after Tutu with a score that Marcus Miller wrote for a 1987 movie set and filmed in Spain, with an all-star cast that included Jodie Foster and Martin Sheen. The subsequent recording evoked Davis and Gil Evans' album Sketches Of Spain for some listeners:

The late 1980s were a busy time for Davis, in spite of growing health problems. In 1989 his autobiography, co-authored with Quincy Troupe, appeared, including searing observations of Charlie Parker and other passages that stirred controversy. His unreleased Columbia-label album Aura, which he considered to be one of his best outings in recent years, finally came out and won a Grammy in 1990. He spent more time on a new artistic vocation, painting and sketching. Davis also continued to tour and to pursue new studio projects, including a reteaming with Marcus Miller for the 1989 album Amandla, and in early 1991 beginning work with producer Easy Mo Bee on a planned double-LP of jazz-rap. We'll hear Marcus Miller's haunting tribute to bassist Jaco Pastorius, who had died in 1987, from Amandla, and the track "Mystery" from the posthumously-released album Doo Bop, which won a Grammy in 1993, despite a decidedly mixed reception from critics:

Davis had always famously resisted revisiting his past, but in his final year he yielded to Quincy Jones' entreaties to perform a concert of the music that Davis and arranger Gil Evans had recorded together in the late 1950s for the albums Miles Ahead, Porgy And Bess, and Sketches Of Spain. Davis said that the ghost of Gil Evans had appeared to him in the mirror and urged him to do the concert; others speculated that the large payday he received didn't hurt matters either. While fellow trumpeter Wallace Roney served as backup and helped carry the brunt of trumpet duties, Davis, who was clearly not in the best of health, managed some memorable moments in the recasting of his masterpieces with Evans, and we'll hear one, along with a performance from his final concert:

Miles Davis and "Hannibal," from his last live performance, recorded at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles on August 25, 1991. A few days after that concert Davis began to vomit blood and checked into a hospital in Santa Monica. During his stay he suffered a stroke and went into a coma, and on September 28, the man who had so often been at the forefront of jazz for the past 45 years died at the age of 65. I remember sitting at a coffeehouse in Bloomington with a jazz musician friend when somebody walked up and told us the news, and how my friend sat there silently, gazing into the distance, his extended pause an acknowledgement of the enormous departure that had now occurred. Space and silence seemed like a fitting response to the loss of Miles Davis. I'll close with a recording Davis made near the end of his life with singer Shirley Horn, whom he had admired and shared a bill with in the early 1960s:

Special thanks to Jim Sangrey.

Final Miles, P.S.

- Star On Miles: The Return Of Miles Davis (Night Lights program devoted to Davis' early-1980s comeback)

- Miles Between: Miles Davis 1961-1963 (previous Night Lights program)

- The Last Word (Paul Tingen's essay for an early version of Warner Bros. The Last Word box-set)

- The Last Miles: The Music Of Miles Davis 1980-1991 (complementary website to George Cole's book)

Outtakes:

Miles Davis and Kenny Garrett performing "Jo Jo" on The Arsenio Hall Show in 1989 (includes an interview):