Black, Brown And Beige is a complex American masterpiece that sets out to broaden a people‘s and a country‘s sense of its history.

In January 1943 bandleader and composer Duke Ellington took his orchestra into Carnegie Hall for the first time, and chose to make his debut with an ambitious 45-minute-long musical depiction of the African-American experience called Black, Brown and Beige. On this edition of Night Lights we‘ll hear music from that concert performance, as well as Ellington‘s subsequent revisitations of his work; we‘ll speak with jazz artist Wynton Marsalis and Ellington historian Harvey Cohen; and we‘ll hear Duke Ellington himself reflecting on his extended composition.

January 23, 1943: the United States and its allies were at war with the Axis powers in Europe and Africa and across the Pacific, immersed in a conflict that encircled the globe. The renowned 43-year-old African-American bandleader Duke Ellington was making his debut that evening at New York City‘s Carnegie Hall, one of the most esteemed concert halls in the world. As Ellington often did in these years, he began with a performance of "The Star-Spangled Banner." The concert was also a fund-raiser for Russian war relief, as the Soviet Union remained under brutal siege from invading German armies. Among the full house at Carnegie were celebrities and artists such as First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, conductor Leopold Stokowski, soprano Marian Anderson, and poet Langston Hughes.

For Ellington it was a dramatic opportunity to present a work that had been a long time forming, a panoramic musical history of the African-American experience that he called Black, Brown And Beige. It was a 45-minute long jazz symphony constructed in what Ellington called "the Negro idiom," and it proved to be an artistic success ahead of its time. Performed at a moment when many scholars believe the Ellington band and its composer to have been at a creative zenith, with the nation in the midst of war and black people still living under segregation, Black, Brown And Beige is a complex American masterpiece that sets out to broaden a people‘s and a country‘s sense of its history. In their essay "Race And Narrative In 'Black, Brown And Beige,'" Lisa Barg and Walter van de Leur write:

Through its successive themes, its restless progression of transitions and modulations, and its sudden changes in tempi and meter, Ellington sought to "parallel" the monumental movements, migrations, and ruptures in racial time and space that have characterized African-American historical consciousness. In blurring the boundaries between myth and history or memory and history, Ellington‘s narrative underscores the epistemological problems of "history" for peoples whose voices and experiences have been erased (or repressed) from official white histories.

The Origins Of "Black, Brown And Beige"

Carnegie Hall was an esteemed venue where very few jazz artists had ever appeared; African-American bandleader James Reese Europe had performed there in 1912, and Benny Goodman and other swing musicians had played it in 1938 and 1939. Duke Ellington‘s debut there was widely covered in the media and seen as a moment of artistic arrival for the composer, who at this point had already been leading a band for nearly 20 years, and had scored numerous hits such as "It Don‘t Mean A Thing If It Ain‘t Got That Swing" and "Don‘t Get Around Much Anymore.". Ellington scholar Harvey Cohen, author of Duke Ellington‘s America, which devotes an entire chapter to Black, Brown and Beige, says the buildup to the Carnegie concert was tremendous, in both the mainstream and the African-American press, and that it may represent, along with Ellington's famous 1956 "comeback" performance at the Newport Jazz Festival, the zenith of publicity and attention in the composer's 50-year-long career.

There were precedents for Black, Brown and Beige, both in the music and historical pageants Ellington was exposed to growing up in Washington D.C., the compositions and concerts of artists such as James Reese Europe, James P. Johnson, and in Ellington‘s own work over the past 15 years-pieces such as "Creole Rhapsody," "Symphony In Black," and his 1941 social-significance musical revue Jump For Joy. And Ellington had talked from time to time in inteviews of an ambitious opus that would tell the story of the African-American experience, from its origins in Africa to its current state in America. It is thought by some scholars that Black, Brown and Beige grew in part out of "Boola," an operatic work which Ellington had cited as being in progress throughout the 1930s.

However long Black, Brown And Beige had been forming in Ellington‘s mind, however, he ended up writing much of it in a six-week sprint, as he recalled to music critic Carter Harmon years later:

After Jump for Joy we came back East, we were out there a couple of years in California, ... and we got back East and we didn't have much promotion when we went back there, and we had a hard time getting proper money going into the Apollo, so I didn't take it, so William Morris (Ellington's agent) says to me, 'What you need is a Carnegie Hall Concert.' So I started whipping up material for a Carnegie Hall concert. And we planned it for - there was a big Russian War Relief, and we played it on 23 January 1943. I think I started writing 'Black, Brown and Beige' on the 19 December. We were playing the theatre in Hartford and Frank Sinatra was the extra added attraction, he was that weekend, when I started and I wrote it was writing all the way down from Hartford down to Bridgeport, Detroit and all these other places, I was always writing in the hotel, backstage at the theatre, Columbus, Ohio, and we got back to New York and introduced Black, Brown and Beige.

What Ellington produced-a 45-minute-long jazz symphony, as well as a long manuscript that provided a wealth of narrative detail for the story he wished to tell, and which has remained unpublished-was extraordinary for its time. He called it "a tone parallel to the history of the Negro in America." Musically, the three-part suite depicted black people brought to America to work as slaves, fighting in wars on behalf of the country that had enslaved them, and searching for a new and better life in the decades following the Civil War. In so doing, he hoped to give African-Americans a deeper historical sense of themselves that would translate into an enhanced modern-day sense of identity. Lisa Barg and Walter van de Leur:

Ellington‘s approach to programmatic expression in Black, Brown And Beige reflects a fluid, dynamic, and improvisatory form of music-narrative relations, and, by extension, a concept of a musical program as a kind of malleable blueprint or set of associative meanings that can-like historical imagination itself-be transported, reframed, and transformed.

As always, Ellington captured a wide spectrum of humanity and emotion in his work, including humor, pathos, pride, and spirituality. Heard in its entirety at Carnegie Hall, Black, Brown And Beige was very much a newly-born work with the Ellington orchestra; certain elements would gain more polish in later reprises. But concertgoers got to hear the full array of devices that Ellington employed to convey his narrative of African-American history. Wynton Marsalis, the Artistic Director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, has performed Black, Brown And Beige with the Center‘s orchestra:

For me as a musician what makes it significant is the craftsmanship of it. Just study it; it's unbelievably well crafted. When you get these kind of genius figures who figure out a lot of things, they have original techniques, they have insights, and those insights are in their art and it‘s in his music. And the sentiment of the piece... I mean when we play it and we‘re rehearsing it, we always are singing tunes from it and saying, 'Psshh, Duke.' He just understood how to put everything together. He understood what binds us, and he had a spiritual insight and he had an optimism that was not naïve, and he had a depth of intellectual engagement with music and of virtuosity and of what a myriad of people could do. So his music is always friendly to all the sections. Great trombones, great trumpets, great saxophones, rhythm section... He gives everybody something to play that is significant and meaningful.

The January 1943 Carnegie Hall concert at which Black, Brown And Beige debuted was in many ways a great success for Ellington; those in attendance that evening gave it an enthusiastic reception. He was booked into New York City‘s popular Hurricane Club for six months afterwards, and throughout the rest of the 1940s he appeared at Carnegie Hall every year, almost always debuting ambitious new works such as "New World a-Comin‘" and "The Liberian Suite," though none came close to the length of Black, Brown And Beige.

Black, Brown And Beige put Ellington into the realm of the concert hall; but not everybody thought that he belonged there. The reviews for Black, Brown And Beige were decidedly mixed, and Ellington found himself under attack from both classical critics such as Paul Bowles and jazz figures such as John Hammond, both of whom criticized Ellington for attempting to work in longer forms. The work's initial reception, coupled with its unavailability for several decades, left it in a sort of limbo. In 1993 Ellington scholar Mark Tucker noted that

Few other works written by Ellington made such demands on listeners or stretched so far the conventions of his art. Few required so much advance planning or later underwent so many revisions and reconfigurations. And no other major Ellington work remained so little known for such a long time; more than 30 years passed between the premier of Black, Brown And Beige and the issue of its complete performance on a commercial recording. Today, surveying the range of Ellington‘s musical achievements, Black, Brown And Beige still looms on the horizon--vast in size yet hazy in outline.

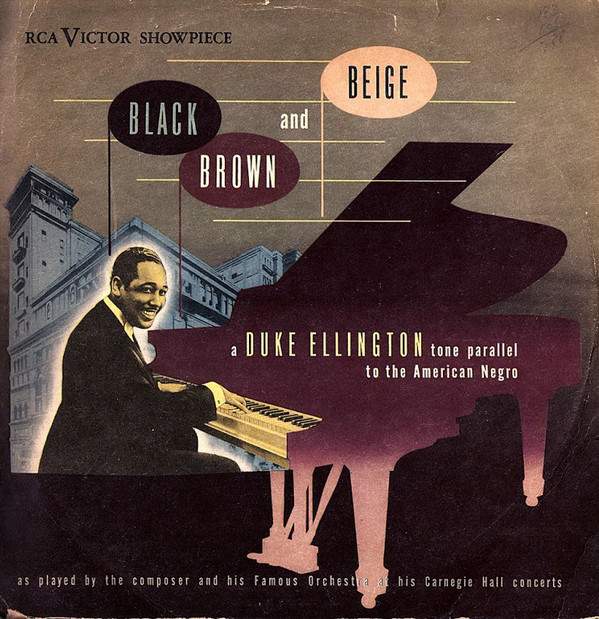

Black, Brown And Beige is known to have been performed in its entirety by the Ellington orchestra only four times, all within the first few weeks of 1943-though Ellington did frequently highlight excerpts from Black, Brown and Beige in the next several years, including the annual Carnegie Hall appearances he made throughout the rest of the 1940s. Ellington historian Harvey Cohen says the work faced several obstacles in gaining wider acceptance, calling it ahead of its time in its scope and concept. Black, Brown and Beige was also hampered by the musician union‘s recording ban that was in effect throughout 1943 and much of 1944. Finally, in December of that year, Ellington was able to record a four-part, 18-minute long version for the Victor label that was packaged in a lavishly-illustrated and notated folio of two 78 records. From that release, here‘s the Duke Ellington Orchestra performing ‘Work Song":

Though Victor‘s deluxe packaging of the double 78 BBB at last made some of the work‘s music commercially available, and though pieces continued to appear in Ellington‘s concert repertoire, Ellington‘s artistic and professional pace carried him away from his landmark work. Still, its importance and Ellington‘s own sense that it had not achieved all that he had hoped it would eventually revived his creative aspirations for it. In 1956 Ellington told music critic Carter Harmon that he was working on an expanded presentation of his jazz symphony that would incorporate some of the unused narrative that he had written for the 1943 concert. That presentation never came to pass. But in 1958 Ellington did make a studio LP called Black, Brown And Beige that refashioned some of the material from the 1943 Carnegie Hall version, and which included a stunning rendition of "Come Sunday" by gospel singer Mahalia Jackson:

There is ample evidence that Ellington never forgot or let go of Black, Brown and Beige; he incorporated some of it into his 1963 opus My People, written for the Century of Negro Progess Exposition in Chicago, and elements appeared in his sacred concerts of the 1960s as well. And in 1965 Ellington made a private recording of the entire work, eventually released more than 20 years later--from that recording, here‘s part of the "Beige" movement, known as "Sugar Hill Penthouse," representing the ascendance of black people to a better life in Harlem:

When Duke Ellington passed away in 1974 at the age of 75, very few people had ever heard Black, Brown And Beige in its entirety. Three years later, the January 1943 concert was finally released as a triple-LP. In recent decades book-length scholarly studies have been devoted to Black, Brown And Beige, and it has been performed by other orchestras, including Jazz At Lincoln Center. Black, Brown And Beige is a musical mural of African-American history that has ultimately realized its creator‘s hopes, even if he did not live to see those hopes fulfilled. Wynton Marsalis:

What makes works of art relevant is the intrinsic value of the art, what is it saying about us as a people. What is it saying about human beings, how does it connect with us. There‘s so much in that piece of music, the form, the structure, the harmonies, the sophistication of it, the message the uplift... It was written during a war time and it tells a tale that‘s important to know about American history. And it‘s Duke Ellington, and the depth of his genius and his insight into the nature of the American proposition was such that when he did things they were significant. This (Black, Brown and Beige) was a thing that was very important to him and it will remain relevant as long as we practice our form of democracy, because his music is relevant to us.

As Ellington himself once said,

For the music that I wanted to hear, it was a matter of hearing people working; bending over a washtub, humming, or just walking through the street in the dark, whistling; or maybe somebody playing a piano, or guitar or something... or you might hear a cat blowing the blues on a whistle on a train. This is all people's music. This is the kind of music when you ask them, say 'What was that?' And they say, 'Oh, nothing.'

Duke Ellington made it into something.

Special thanks to Harvey Cohen, Todd Gould, Wynton Marsalis, Michael Paskash, Kay Peterson, Casey Zakin, and the Smithsonian Archives Center.

More About Duke Ellington And African-American Heritage Jazz

- A Sprawling Blueprint For Protest Music (NPR segment on Black, Brown And Beige)