(NOTE: some of this content previously appeared in a post that I wrote for NPR's "Take Five" feature: History as Symphony: The African-American Experience in Jazz Suites)

During the early part of the 20th century, African-American composers began to write extended musical depictions of black American life. Pianist James P. Johnson penned Yamekraw: A Negro Rhapsody. Scott Joplin wrote his opera Treemonisha (it was not staged, however, until 1972). Perhaps most successfully, William Grant Still composed his Afro-American Symphony in 1931.

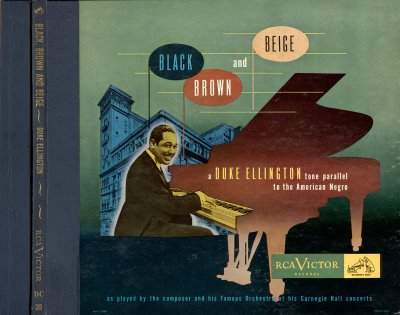

Ellington's "Musical Evolution"

That same year, Duke Ellington told a reporter, "I'm going to compose a musical evolution of the Negro race." It took Ellington 12 years to achieve his goal. The 45-minute-long Black, Brown and Beige Suite: A Tone Parallel to the History of the Negro in America, is now considered one of his greatest works.

Black, Brown and Beige was the first of several large-scale orchestral jazz compositions to trace the journey of black people – from Africa to enslavement in America to emancipation to the subsequent difficulties and complexities of life in a racist and segregated country. Ellington originally conceived of the suite as a five-movement work he called Boola, which would be divided chronologically into Africa, Slaveship, Plantation, Harlem, and a finale.

Energized by the completion of his 1941 musical Jump For Joy, Ellington finally wrote Black, Brown and Beige in a burst of just a few weeks, before his January 1943 debut at Carnegie Hall in New York City. The audience received it enthusiastically, but New York critics were less kind; Paul Bowles called it "formless and meaningless," while John Briggs of the New York Post said, "Mr. Ellington was saying musically the same thing he had said earlier in the evening, only this time he took forty-five minutes to do it." Jazz impresario John Hammond was moved to write an article entitled, "Is the Duke Deserting Jazz?"

Although he would never perform it again in its entirety, Ellington continued to revisit Black, Brown and Beige periodically over the rest of his career, making studio recordings of its various movements in 1944, 1958, and in the mid-1960s.

Oliver Nelson's Long History

Nearly twenty years later, saxophonist and composer-arranger Oliver Nelson weighed in with Afro-American Sketches, a jazz suite in seven parts. Unlike Ellington, Nelson undertook his project with some reluctance. In the liner notes to the album he attributed his initial hesitancy to "the lack of honesty in a lot of Afro-jazz LPs on the market.... I didn't know a lot about Africa, African people and culture and, most important[ly], ...African music and rhythm."

After embarking on an intense study of those subjects, Nelson began his musical history. Afro-American Sketches begins with the conflicts between African natives and slave traders, and ends during his own era, with the Freedom Riders of 1961. "I have at last realized the importance of my African and Negro heritage," Nelson concluded in the liner notes, "and through this enlightenment I was able to compose 40 minutes of original music which is a true extension of my musical soul."

Nelson would go on to compose and record an extended work with an explicit Ellingtonian allusion, a tribute to Martin Luther King Jr. called Black, Brown and Beautiful.

John Carter's Epic

Texan clarinetist John Carter's epic, five-album suite Roots and Folklore: Episodes in the Development of American Folk Music was recorded over the course of the 1980s. "What the African brought with him gave way to the blues, church music, jazz, rock, and all forms of American music," Carter stated. "I wanted to contribute some musical thoughts of my own in an artistic, historical way."

Critic Gary Giddins calls Roots and Folklore "a capacious vision of America's motley musical history.... Fields [one of the albums that makes up the suite] counters the prevailing lack of ambition and fear of innovation that stifled so much recording during the 1980s."

Of the obstacles facing jazz artists in the '80s who wanted record companies' support for innovative, orchestral projects, Giddins writes, "Carter solved the first problem by voicing his musicians in such a way as to suggest a larger group and the second by refusing to accept the idea that by virtue of recording he is in the business of producing marketable product."

Wynton Marsalis' Historical Opus

In the 1990s trumpeter and composer Wynton Marsalis added his own African-American historical opus to this canon of extended works. Although his recording of that piece, Blood On the Fields, earned Marsalis the first Pulitzer Prize ever awarded to a jazz musician, it received mixed reviews from jazz critics.

"Marsalis is working at a particularly difficult point in time. He doesn't quite get credit for what he's done," says historian Michael McGerr. "He's writing at a time when black activism has a history, and has a heritage — and in a new way, that isn't simply commemorating a slave past, but also deals with the 20th-century inheritance of black struggle in the cause for freedom."

On The Program

InSuite History: Jazz Composers And The African-American Oddessey, we'll hear music from all four of these extended African-American musical histories. We'll talk with author and scholar Michael McGerr about the historical contexts from which these recordings emerged.

For More About Jazz Musical Histories...

• Read the full version of my interview with historian Michael McGerr:

Michael McGerr on "Suite History," Part 1

Michael McGerr on "Suite History," Part 2

• Read a blow-by-blow analysis of the January 1943 performance of Ellington's Black, Brown and Beige:

I. Black

II. Brown

III. Beige

• Listen to the January 1943 performance of "Brown" in the previous Night Lights program When Betty Met the Duke: Betty Roche.

• Listen to John Gennari discuss the critical reaction to the debut of Ellington's work in the previous Night Lights program, A Few Words About Jazz, which also includes an excerpt of the 1943 Carnegie performance of "Black."

• Read the long narrative treatment that survives of Ellington's Boola, which illuminates the plot and traces its evolution into the Black, Brown and Beige symphony.

• Take a look at this photo of Ellington's '78 folio by Antony Pepper.

• Listen to Michael McGerr on the WFIU documentary Jump For Joy: Duke Ellington's Celebratory Musical.

• Hear parts of Oliver Nelson's Black, Brown and Beautiful on the Night Lights program Dear Martin.