Malibu House co-owner Max Meckes speaks with WTIU News' Bente Bouthier. (Devan Ridgway, WTIU News)

In less than a year, Max Meckes has opened five sober living homes and a headquarters in Bloomington. Taxpayer money and donations from non-profits have helped sustain the operation, called Malibu House.

Malibu House’s Facebook page describes obtaining food, beds, appliances, computers, and other items for the homes, but it’s often ambiguous about whether they were purchased or they were gifts.

The page says Malibu House is a “Charity Organization.” On several occasions, Malibu House has solicited donations on social media, including one last October that said, “Cash donations for Malibu can be paid through check or Cash App at $malibusoberliving.”

But Malibu House is not a charity organization.

Unlike non-profit sober living homes in Bloomington such as Amethyst House and Courage to Change, Malibu House is registered with the state as a Domestic Limited Liability Partnership. A review of Malibu House’s recently-redesigned website and its previous iteration showed no mention of its business status.

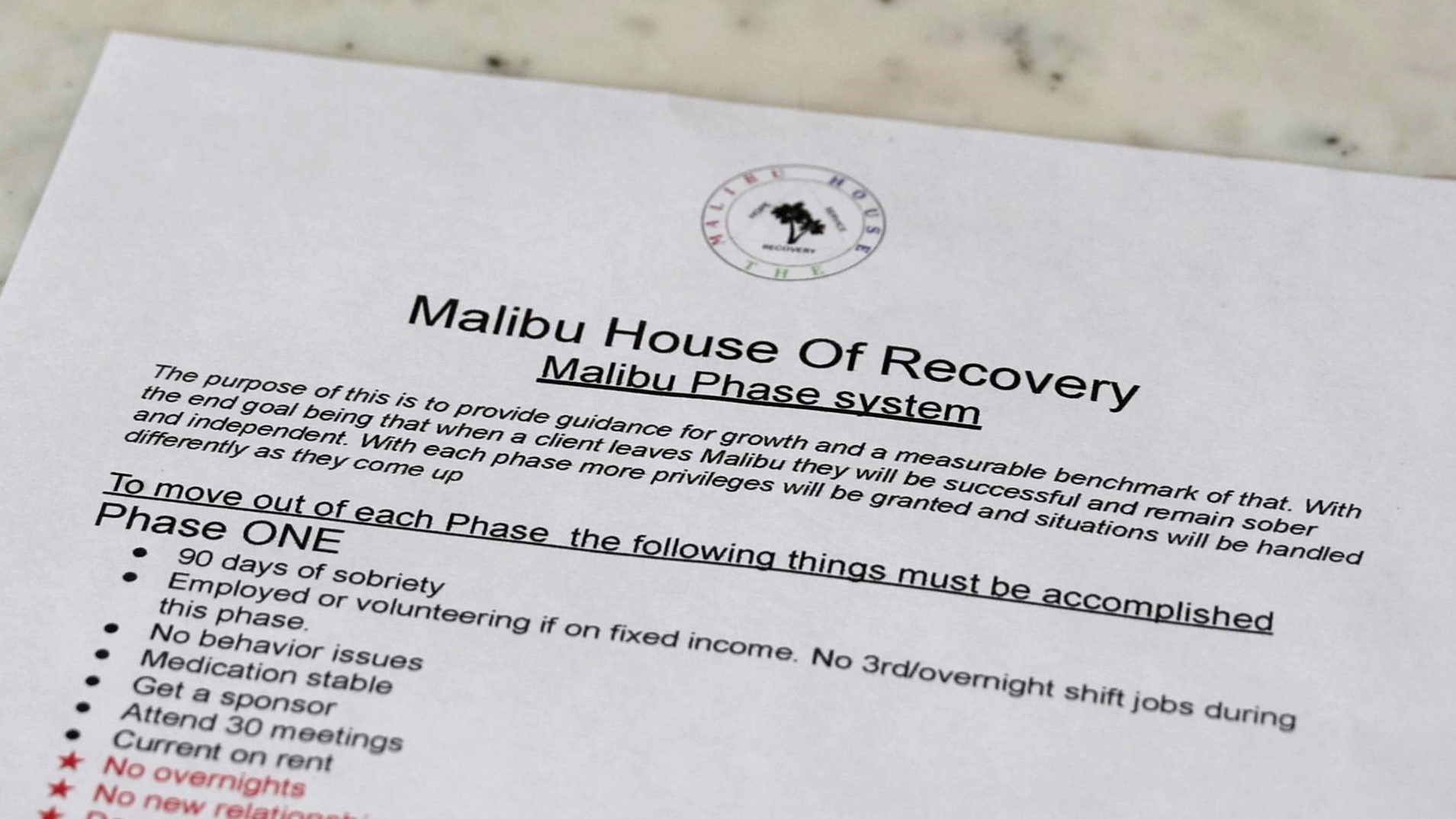

Malibu House operates at a level of residential recovery — it doesn’t have clinical services — with little regulation in Indiana. That’s despite dealing with vulnerable people paying to live in a place that helps them beat addiction to drugs and alcohol.

Malibu House has posted on social media a one-time “bed fee” of $150 and rent of about $125 per week. Just the rent for a house with 10 people would bring in about $5,000 per month. Meckes has at least five homes that the rental company Pendragon was advertising at $1,650 to $2,750 per month.

The residents of such homes are sometimes ordered there by a court after drug-related offenses. Some go voluntarily because they’ve relapsed.

In an interview with WTIU/WFIU News, Meckes said he is clear about the company’s for-profit status “if anybody comes up and asks.” He said he is a recovering addict and has been sober “going on three years.” Malibu House’s rapid growth, he said, reflects the need for what his company provides, and he pointed to numerous successes involving recovering people with substance use issues.

Meckes, 40, also acknowledged his long record of arrests, including a pending case in Warrick County scheduled for trial in June. According to the probable cause affidavit, Meckes is alleged to have stolen 51 bottles of liquor worth almost $1,700 from a Walmart in October 2023.

Meckes also has a pending case in which he’s accused of loaning an uninsured car to someone who caused a crash in March 2024 that did at least $7,600 in damage to the other car.

Meckes is on probation until 2029 after pleading guilty last October to resisting law enforcement and, in a separate incident, entering his parents’ home without permission through a window.

“I'm an easy target. You know, my past is horrendous, right?” Meckes said. “I've been arrested all these times. I've done all kinds of stupid things. You know, I'm easy to come at, but I'm doing what I can right now to try to help other people and take myself out of the equation.”

As a for-profit company, though, Meckes and his co-founder, Amanda Cecil-Campbell, are very much in the equation to do what all for-profit companies strive to do — make money.

Max Meckes, aka Kiel Sheppard

Meckes used to be known as Kiel (pronounced Kyle) Sheppard, which is the name on most of the public documents related to his arrests.

In 2015, fans at a Luke Bryan concert in West Palm Beach, Fla., reported to police that young children were in a car by themselves with the motor running and the air conditioning on. According to police, Sheppard and a woman left 9- and 11-year-olds — and the family’s pet bird — alone while he said he was selling tickets. Police arrested Sheppard on charges of child neglect.

In 2016, Sheppard and two other men were arrested in Scranton, Pa., for theft in what news reports described as $100,000 in stolen passes to a music festival. The Lackawanna County Sheriff’s office told WFIU/WTIU News that there is still a warrant for Sheppard’s arrest for unpaid court fees of $741.

In 2017, in Gulf Shores, Ala., police arrested Sheppard for selling stolen staff and vendor wristbands outside a music festival, according to a press release from a sergeant with the Gulf Shores Police Department. The release said Sheppard had counterfeit bills in his possession as well. It also said that a year earlier, the department arrested Sheppard under similar circumstances.

Meckes’ most recent drug-related arrest was less than three years ago, for possession of methamphetamine and resisting law enforcement.

“I do have a past,” Meckes said. “I've been in active addiction for a long time, and my past is what uniquely qualifies me to be so relevant in this field. I have the experience that I've been through, what these people are going through now at Malibu House, that I'm able to share with them. I can relate with them on the same field. I will tell you that since we started Malibu House, you won't find anything new (arrests).”

Partners?

Before an inquiry from WFIU/WTIU News last week, the Bloomington non-profit Healing Hands was listed on Malibu House’s website as a “partner.”

The website even displayed Healing Hands’ logo and a nine-minute “testimony video” praising the organization. In the video, Meckes and Cecil-Campbell told a story about a refrigerator that stopped working at one of their homes.

“We didn’t have the money to go buy a new refrigerator,” Meckes said. “So we started figuring out where we could find one. That’s when Healing Hands came and helped us. … A few hours later, they said, ‘We bought a new refrigerator for you. It’s at Lowe’s. You can pick it up today.’”

The video does not appear to be linked on Malibu House’s redesigned website. While donations of personal items such as clothes are presumably retained by the people in need, applicances such as refrigerators amount to infrastructure for a business.

Kristin Castro, executive ministries director and dream team pastor at Healing Hands’ affiliate, City Church For All Nations, said the organization only learned last month that Malibu House was for profit. On the same day as WFIU/WTIU News’ inquiry, City Church for All Nations issued a statement saying, “Malibu House is not a partner or program of City Church or Healing Hands, but the organization and its residents have received physical donations as members of the community we serve.”

Healing Hands’ website addresses its stewardship of money.

“At Healing Hands, we believe that transparency and financial responsibility are vital to building trust with our supporters and the communities we serve,” it says.

But after issuing the statement, Healing Hands didn’t respond to a question about whether its benefactors know that some donations have gone indirectly to for-profit Malibu House.

Healing Hands’ website promotes a charity dinner March 28 called “A Night of Hope.” The top sponsorship category, Platinum, goes for $5,000.

Malibu House also appeared to connect itself to Indiana University. A social media post thanked IU Surplus Stores “for providing us with iMacs and 75” smart TVs for all our sober living homes!”

The computers and televisions were “provided” at a price. An IU spokesman said the university sold the items to Malibu House.

The Salvation Army’s logo was listed on Malibu House’s website as a “partner” until the recent redesign. Vinal Lee, pastor and director of The Salvation Army of Bloomington, said the well-known organization has provided payments to Malibu House for some residents’ first week of housing.

He said Malibu House helps The Salvation Army achieve its goal of getting more people housed, and that for-profit status makes no difference. But he added that if Malibu house were non-profit, “A benefit is that it would release a level of liability from Max and give, I think, a clearer transparency and accountability that the income being generated from Malibu isn't for the benefit of one individual.”

Anthony Grimes, vice president of the National Alliance for Recovery Residences (NARR), which sets standards for state certification, said groups such as Healing Hands and The Salvation Army should have understood much sooner about Malibu House’s for-profit status. That’s especially the case since they were listed as “partners.”

“I think it's something that should have been caught on the front end, so to speak,” he said. “We talked about truth and advertising and marketing materials. These different things in the (NARR) standards become expectations that these organizations are measured by.”

According to public records, Perry Township has paid almost $10,000 to Malibu House since 2024 as township assistance for low-income residents to live there. Township trustee Dan Combs declined to comment until he learns more.

Donations to Malibu House, as opposed to those made to non-profits, are not tax-deductible. Meckes said his donors understand that.

‘How society should be’

As a leader of a national association, Grimes said when opening five houses within a year of starting, as Malibu House did, accountability becomes especially important.

“These physical environments, the actual space that they live in, they have to be inspected,” said Grimes, a recovering addict and with an arrest record himself. “They have to be walked through. There are things like Naloxone that has to be present. There are things like overdose procedures that have to be in place. Because those are the things that I can tell you here in Virginia that directly save lives. … It just sounds like nobody in Indiana is really paying attention.”

Indiana’s Family and Social Services Administration regulates residential recovery homes, but homes that don't receive state money do not have to be certified.

Meckes said Monroe County Sheriff Ruben Marté has visited his business. Marte told WFIU/WTIU News that Meckes invited him and that he went to the company’s headquarters and one of the five houses, the women’s home. Marté said that as a law enforcement officer, he found “nothing amiss.”

Eric Wolfe, who lived at two of the Malibu House residences, said there were problems with overcrowding. He said around 12 to 16 people lived in one house on Chris Lane. The home is for a single family, according to city property records.

NARR’s standards say there should be at least 50 square feet for each person assigned to a bedroom.

“Just too many people in one place,” Wolfe said, “and you're dealing with people who have mental problems and addiction problems, and you just shove them in a house with as many as it'll take.”

Wolfe added that residents with Malibu were asked to help with manual labor for Meckes’ other homes. Lee from The Salvation Army said Malibu has been “providing volunteers for us.”

Meckes said Wolfe is a disgruntled former resident who was behind on rent and uninterested in recovery and independence.

After the interview with WFIU/WTIU News, Meckes did not respond to a follow-up question about overcrowding. He denies that residents are pressured to work for him.

It’s uncertain how Meckes obtained money to start the sober living business. Public records show he does not own any of the properties being used by Malibu House.

In a 2022 court filing, Sheppard told the court he had no money. In October of last year, a court ordered “payment of pauper attorney fees” — $1,325 — from the county to a lawyer for representing Sheppard as a public defender. Meckes said that was for an old case that took a long time to resolve.

In January of 2024, a lawsuit for back rent was filed against Meckes by a landlord. Meckes said he did stop paying rent and applied the money to opening Malibu House. He said he eventually paid what he owed and the case was dismissed. Meckes said he and Cecil-Campbell also used money from work and savings to start their business.

Meckes said that donations from non-profits and manual labor from his residents is just part of the Malibu House community. The company’s website says a sixth home is “coming soon.”

“This is how society should be, right, if we all help each other, if we're out there for the right reasons,” Meckes said. “This world could be such a better place, and that's what we're trying to do.”

Contact WFIU/WTIU News reporter Bente Bouthier at bentbout@iu.edu or 812-727-4016.

Mark Alesia edited and contributed to this story.

Continuing coverage: New questions raised about for-profit addiction recovery business Malibu House — and its Bloomington neighbor