In 1840, the largest city in Indiana was New Albany, with 4, 226 people. The state capital, Indianapolis, was second with 2,692; Richmond was third, with 2,070, and Crawfordsville was fourth, with 1,327.

There’s a marked absence of certain other cities: Fort Wayne, Lafayette, and Logansport, for example. All of those places were settled by 1840, yet more than four-fifths of the people of Indiana lived in the southern half of the state. In fact, the population was so concentrated in the south that one-half of the settlers lived within seventy-five miles of the Ohio River.

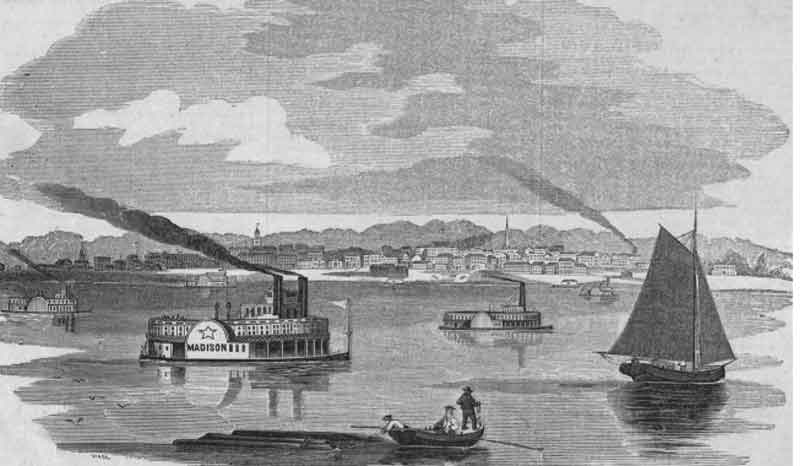

Surely those northern burgs grew enough by 1850 to make the top three? In fact, in 1850, the New Albany-Jeffersonville area was once again the most densely populated section of the state, with slightly over ten thousand people. The second largest city was also southern—Madison, with 9,007 people; Indianapolis came in third, with 8,091 inhabitants. The numbers beg the question: why did Indiana’s population settle in the south first?

Historians have identified three main reasons why settlers by and large entered the state from the south, instead of the east and north. First, southern Indiana bordered Kentucky–a state since 1792, one of the first areas settled in the huge trans-appalachian migration of the early republic, and, relative to Indiana, heavily populated. In 1810, Kentucky claimed more than 400,000 residents; by 1840 the number had nearly doubled. An 1818 handbook written for those migrating to the western frontier advised that “‘Kentucky has passed the era of rapid increase from emigration. The best lands are sold and have become expensive.’”

Indiana offered much cheaper farmland to those who were willing to clear the land themselves and build their own shelter. The same handbook praised Indiana as being “intersected or bounded in all directions by navigable rivers or lakes, enjoying a temperate climate and an immense variety of soil.” The handbook also noted that nearly two-thirds of its territory was still in the hands of “Indians” in 1818, but rather ominously cast that fact as a “temporary evil, that a short time will remedy.”

The second reason that most settlers came to southern Indiana relates to the best available migration routes westward in the days of early Hoosier statehood. In 1818, the National Road had reached Wheeling, West Virginia; for much of the next decade the road was built through Ohio and did not reach Richmond, Indiana, on the state’s eastern border, until 1827. Water transportation down the Ohio River was still a primary route for migrants in the first decades of state history. Those migrating into the state from Kentucky and further south, often relied on the old Wilderness Road, running across Kentucky to Lexington, Bardstown, and Louisville.

The third and final reason was familiarity: people arriving in southern Indiana found soil, forests, and valleys that reminded them of what they had left behind in their southern home states. Indiana’s new settlers brought southern attitudes with them to the North. Many of these plain folk farmers, millers, and carpenters were suspicious of those who made their living from urban businesses, especially land speculation, believing that the only honest money was made through labor. The southern Indiana farmer looked with suspicion on city dwellers— “‘the white fingered, and perhaps light fingered, fops and dandy lawyers of Indianapolis, many of whom never did an honest day’s work in all their lives’”.

Southern Indiana has long since ceased to be the population leader of the state, but the hard-nosed, commonsensical attitude toward life and work brought by migrants to that region survived for many years in the Hoosier state.

A Moment of Indiana History is a production of WFIU Public Radio in partnership with the Indiana Public Broadcasting Stations. Research support comes from Indiana Magazine of History published by the Indiana University Department of History.

IMH Source Article: Roger H. Van Bolt, “The Indiana Scene in the 1840’s,” Indiana Magazine of History 47, no. 4 (Dec. 1951): 333-356.