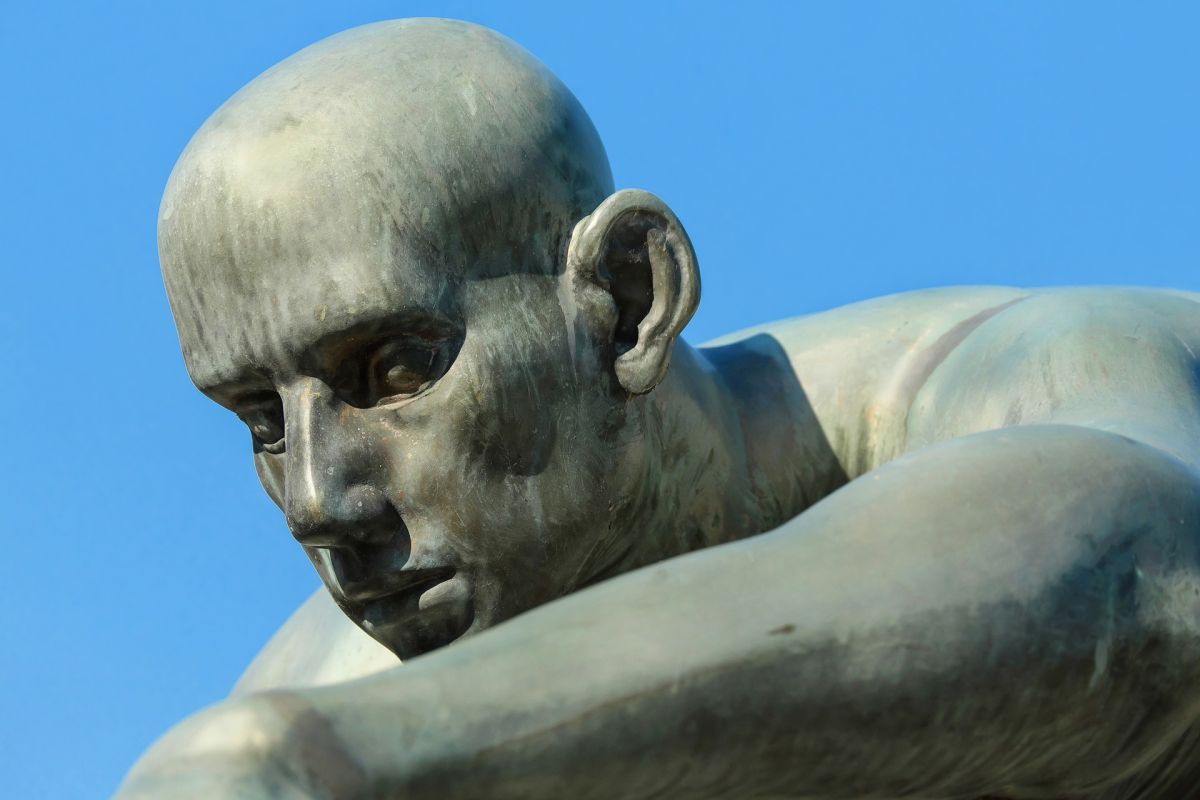

Use your noggin as we explore music all about the head! (Pixabay)

For the next few weeks of Ether Game, we'll be exploring some musical anatomy, that is, pieces of music about different body parts. We're calling it "Body Of Works" (our tongue-in-cheek title, puns intended) and we're focusing on a different body part each week*.

To kick things off, we'll start at the very top-the top of the body, that is. This show we'll be all about "head" music, including eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and everything in between.

Here's our "cerebral" playlist.

*Be sure to check out our other shows about Hair, Limbs, and the Torso!

- Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), St. Matthew Passion: "O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden" ["O Sacred Head, Now Wounded"] – One of the most fascinating aspects of Bach's Passions is the use of Lutheran chorales. They have a theological function-relating a song known by the entire congregation to an appropriate place in the Passion story, and inviting audience participation. In the St. Matthew Passion, they also serve a structural role: Bach sets the same chorale, "O Sacred Head, Now Wounded" multiple times, with a different text and harmonization each time. We heard a couple of those different settings in tonight's excerpt. For a long time, the St. Matthew Passion was thought to have been first performed on Good Friday Vespers 1729, but it was probably performed two years earlier. This incorrect date was further solidified by a supposed centenary performance in 1829, under the baton of Felix Mendelssohn. Though he was slightly mistaken on his dates, Medelssohn's performances of Bach's larger works were responsible for the revival of Bach's music that continues to this day.

- Richard Strauss (1864–1949), Salome: Final Scene – The gruesome tale of Salome, the step-daughter of King Herod, has long been an inspiration for some great, albeit disturbing, pieces of art. According to the Gospel of Matthew, John the Baptist was being held in prison for criticizing Herod's new bride, Herodias. On Herod's birthday, his stepdaughter performs the highly sexual Dance of the Seven Veils. Herod is so aroused that he offers anything to Salome as a reward for her performance. She asks for only one thing: the head of John the Baptist on a silver platter. Oscar Wilde's play Salome (and Strauss' opera of the same name), takes the story to another level by portraying Salome as having an incredibly sexual crush on John the Baptist. When he refuses her, her anger gives fuel to her bloody request. Both Wilde's play and Strauss' opera caused a stir when audiences watched the violent spectacle unfold on stage, especially when Salome kisses the severed head in this final scene.

- Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975), The Nose – Here's the general plot of Shostakovich's surreal opera The Nose: a petty bureaucrat named Kovalyov awakes one morning to find that his nose has detached itself from his face and run away. When he finally finds his nose, he discovers that it can now walk, talk, and sing, and (to make matters worse) his nose also now outranks him professionally. The story is a savage satire of bureaucracy, while subtly emphasizing the importance of olfactory politeness and good hygiene in high society. The original story was actually written in the mid-nineteenth century by author Nikolai Gogol, and adapted by Shostakovich almost a century later in 1928. Shostakovich wrote this during the brief time when the Soviet government was lax about the content of modern art. But a few years later, they cracked down on surrealism and political satire, and The Nose wasn't performed again until 1974.

- Gustav Mahler (1860–1911), Songs of a Wayfarer: "Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz" ("The Two Blue Eyes of my Beloved") – Gustav Mahler was known to recycle old melodies, especially his Lieder. For instance, he used several of the melodies from his song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) in his first Symphony. Mahler wrote the text to this song cycle, so perhaps that's why he felt comfortable abandoning the themes of the poetry when the melodies show up in the Symphony. His fourth and final song from the cycle, the love song "Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz" ("The Two Blue Eyes of my Beloved") has nothing to do with eyes when it shows up as the major-key section of the third movement of the Symphony. Instead, the movement is a mash-up of other odd musical references. Mahler opens the movement with a canon on the tune "Frere Jacques" (or "Brüder Martin" in German) set in a minor key. Later, he includes a section that sounds like it's being played by a Jewish klezmer band.

- Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), Third Book of Madrigals: "Occhi un tempo mia vita" ("Eyes that were once my life") – Madrigals were incredibly popular in the Renaissance. For one thing, they were full of intense romantic poetry, and consequently, full of body parts: beating hearts, fluttering hair, reaching hands, and-of course-hauntingly beautiful eyes. In addition, they were often easy enough to sing at home. That changed at the end of the 16th century when Claudio Monteverdi became one of the most popular madrigalists around. The madrigal we just listened to is one of the last that Monteverdi wrote before he started to change the traditional rules of Madrigal composition. By the time he published his 5th book of madrigals, he followed what he called his "seconda pratica" or "second practice." In essence, this style of composition manipulated dissonances in service of the madrigal text and expression. Eventually the seconda pratica would evolve into opera, with Monteverdi's L'Orfeo hailed as one of the first examples of the genre.

- Robert Schumann (1810–1856), Dein Angesicht ("Your Face") – Schumann's song "Dein Angesicht" ("Your Face"), based on a poem by German poet Heinrich Heine, was written in 1840, his famed Liederjahr or "Year of Song." On the surface, it seems like a love song, extolling the beauty of a lover's face "so lieb und schön" ("so dear and beautiful"). But the poem turns dark when the singer sees a vision of the face pale, full of pain, and soon to be extinguished by death. This study in contrasts (beauty and death) was common in German Romantic poetry. It was also written at a time when people were fascinated with the macabre face of death, seeing it as something lovely and worth preserving. The faces of notable people were often cast in plaster shortly after their death and preserved as "death masks." Schumann wasn't notable enough to earn a death mask, but fellow composers Haydn, Chopin, Liszt, and Beethoven all had death masks made of their faces when they died.

- Guillaume Dufay (c. 1400–1474), "Se la face ay pale" – Composer Guillaume DuFay was the illegitimate son of a single woman and a priest whose name has not come down to us. His musical talent drew attention early on, and by the time he was 18 he had already reached the level of subdeacon. During his career he served in various locales, including Cambrai, Bologna, Rome, Savoy, and Lausanne. He was considered the leading composer of his age. Many composers were attracted to his popular ballade, Se la face ay pale, which DuFay composed while in Savoy. Typical of the ballade, the text features frequent rhyme and word play, and describes the pallid face of a dejected lover. Dufay later took Se la face ay pale and turned it into music for a mass. It is one of the earliest surviving masses of its kind, in which each movement is based on the same secular melody.

- Eric Moe (b. 1954), Mouth Music – It's pretty clear from listening to even a moment of this piece why composer Eric Moe decided to call it Mouth Music. All the sounds from the work were made by mouths-mostly the mouths of friends who were staying with Moe at the MacDowell artists' colony in New Hampshire around 1995. Instead of typical mouth music (aka, singing), this piece is comprised of gurgles, hums, whistles, laughter, coughs, and other kinds of strange noises our mouths are capable of creating. Eric Moe is a highly-decorated composer, receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship among several dozens of other commissions and awards. Although he does write for more traditional instruments, his specialty is "electroacoustic" music, real acoustic sounds recorded and manipulated using electric means. He currently runs the electroacoustic music studio at the University of Pittsburgh where he also teaches composition.

- Irving Berlin (1888–1989), "Cheek To Cheek" – We're fairly certain the cheeks Irving Berlin is talking about here are the ones on your face-that's why it's on tonight's show. If he were talking about some other kind of cheek, let's just say that would make for an unusual kind of dance. When this song was first performed, the two people dancing "Cheek To Cheek" were Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, when they introduced the song in the 1935 film musical Top Hat. And people were all ears when "Cheek To Cheek" started playing. The song became quite popular almost immediately, hitting number one on the hit parade for several weeks and becoming the top-selling single of 1935. Unfortunately, its popularity couldn't help its critical success. "Cheek To Cheek" lost out on the Oscar for Best Song to the Harry Warren song "Lullaby of Broadway."