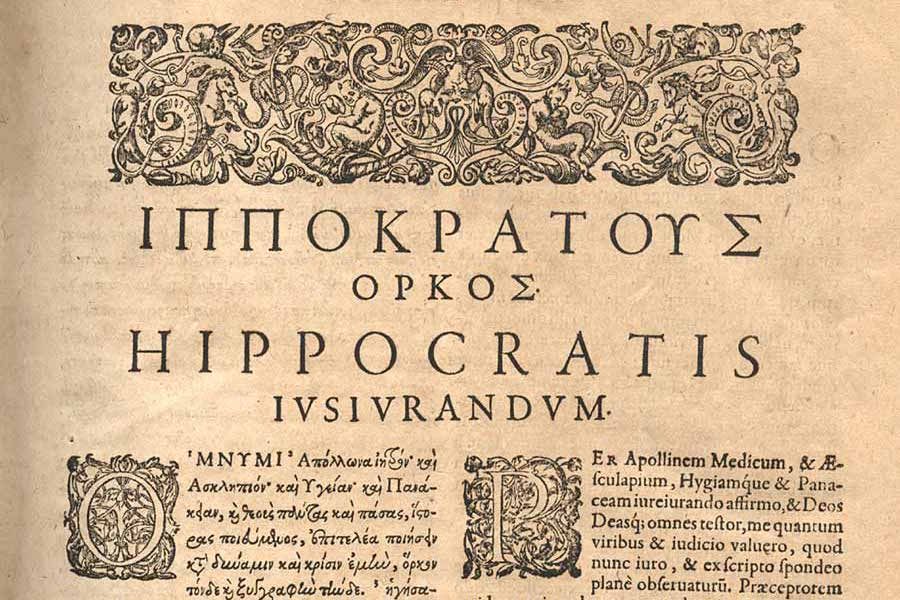

A printed edition of the Hippocratic oath in Greek and Latin, published in Frankfurt in 1595. (Wikimedia Commons)

In the first part of this series on ancient science, we saw how the Assyrians recorded the earliest known observation of a solar storm, as well as how they tried to understand and treat epilepsy. In the second part of the series, we look at how writers and thinkers in ancient Greece continued the eastern tradition of medicine by investigating Hippocrates and the Hippocratic corpus.

The phrase "do no harm" famously comes from the Hippocratic Oath, a piece of writing from ancient Greece, and is still a core aspect of medical ethics today. As its name suggests, the oath was ascribed to a doctor named Hippocrates early on, along with a sizable collection of other writings called the Hippocratic corpus.

Modern scholars, however, think it's unlikely Hippocrates wrote most of the corpus that bears his name, including the oath, although they do think someone named Hippocrates lived around 500 BCE. This raises more questions. If Hippocrates didn't write the oath, who did? And who was Hippocrates?

In addition to the Hippocrates corpus, there is a wide variety of writings either attributed to Hippocrates or describing his life and work, all of varying reliability. Generally speaking, the earlier the source, the better. One of the earliest writers to mention Hippocrates is Plato, in his dialogues Protagoras and Phaedrus, written in the early 4th century BCE.

Plato says that Hippocrates was from the city of Cos, in what is today Turkey, and that he was a descendant of Asclepius, a legendary figure associated with medicine. He also connects Hippocrates to a certain methodology of understanding the whole of a given system in order to understand a part of it.

This has been interpreted by some scholars to mean that Hippocrates studied human biology in order to better understand medicine. This is in keeping with what is known about earlier philosophers like Empedocles and Democritus who are known for writing about both natural science and medicine.

There is also an anonymous fragment from the same time as Aristotle, Plato’s younger student, that gives more detailed information about Hippocrates’ ideas regarding the biological origin of diseases. According to this document, Hippocrates thought diseases were produced by breathing in excessively hot or cold air, and that the various temperatures produced the variety of diseases.

Later sources supply more details about Hippocrates, but are likely inventions by later writers. What remains are all of the writings attributed to Hippocrates, including the oath. They were probably thought to have been written by Hippocrates because they expressed similar ideas to the ones Hippocrates was known for. These writings display a wide variety of views, however.

What is interesting from a scientidfic perspective is the association many of the documents make between natural laws. Laws that govern all of nature, including human beings. One of the works, Airs, Waters, Places, argues that different climates produce different effects on human beings, and concludes that this why there are differences between cultures.

It’s specific claims are no longer very accurate, but its belief in the environmental underpinnings for living organisms is an earlier form of ecology. Animal species, not just humans, do differ in relation to their natural environments, although in ways far more complex than the Hippocratic corpus can hope to explain.

Hippocrates may not have written the famous oath, but he was a representative part of a major turning point in the history of human science, when medicine became part of the rational study of the natural world.