By January 2023 COVID-19 had killed six point seven million people. It is one of many well-known diseases caused by a virus. The common cold, the flu, and measles are others. But, what is a virus, anyway?

Nineteenth century doctors discovered that some diseases are spread by tiny particles smaller than any bacterium. The particles—viruses—are too small to see with an ordinary microscope. They can be imaged only with the more powerful electron microscope.

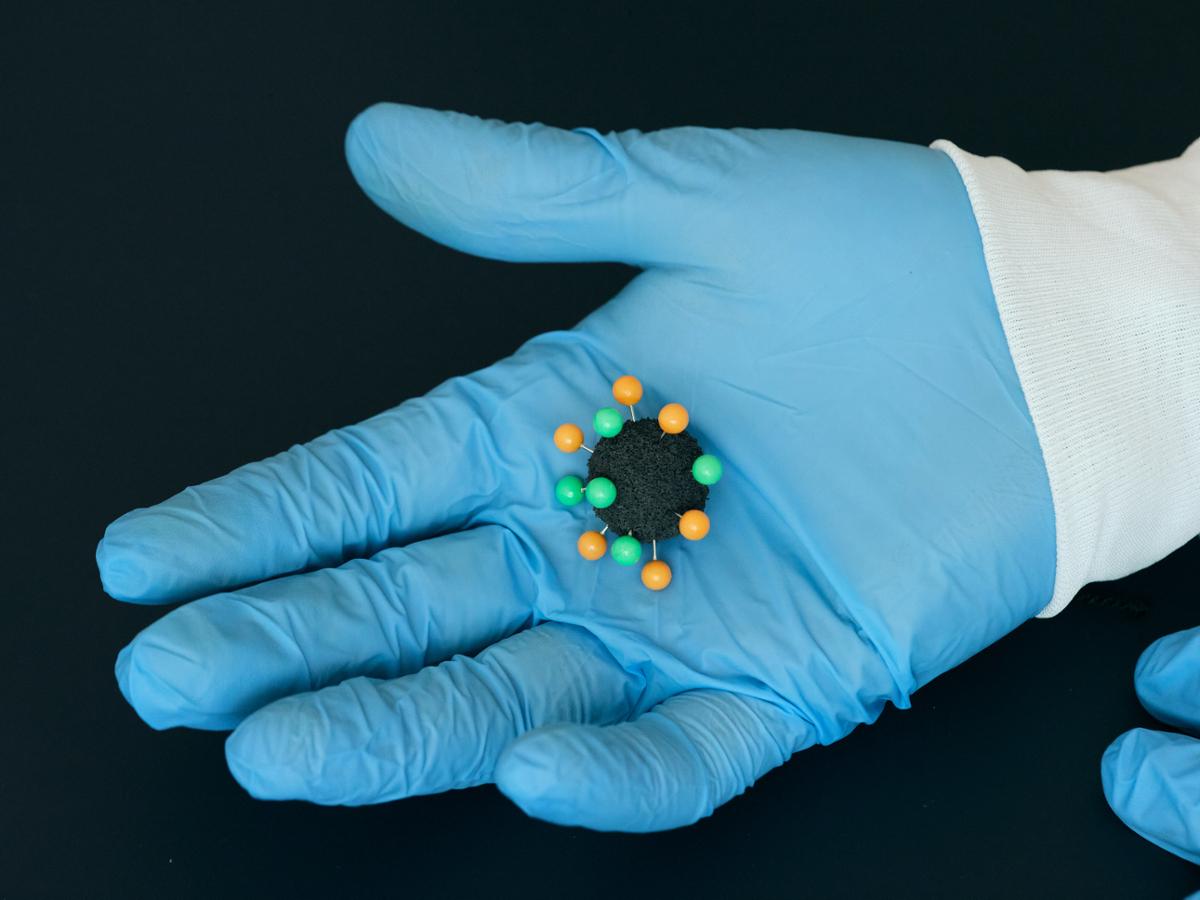

Though biological, viruses aren’t actually alive. They have no metabolism—they never eat, don’t need oxygen, and produce no waste. By themselves, they can’t reproduce. A virus can be as simple as a strand of nucleic acid surrounded by a protein coat. Viruses proliferate because they trick living cells into making more copies of the virus. A virus’s protein coat includes specialized proteins that allow it to latch onto the sugars, proteins, and lipids of a host cell and enter it.

Ordinarily, DNA contains the cell’s own instructions for making proteins it needs to live. But a virus genome, instead, contains instructions for making copies of the virus. It commandeers the cell’s living machinery to make more viruses. The new viruses spread to other cells, repeating the process. The side effects of this process can make the host organism sick.

Living things have multiple means of protecting themselves against viruses. Among them, the immune system has specialized cells that detect, swallow, and destroy viruses based on substances in their protein coat. A vaccine works by exposing the immune system to these substances, teaching it to recognize the virus, so immune cells are ready to attack when it arrives.