MUSIC CLIP - OSCAR PETERSON, “MOONGLOW”

Welcome to Afterglow, a show of vocal jazz and popular song from the Great American Songbook, I’m your host, Mark Chilla.

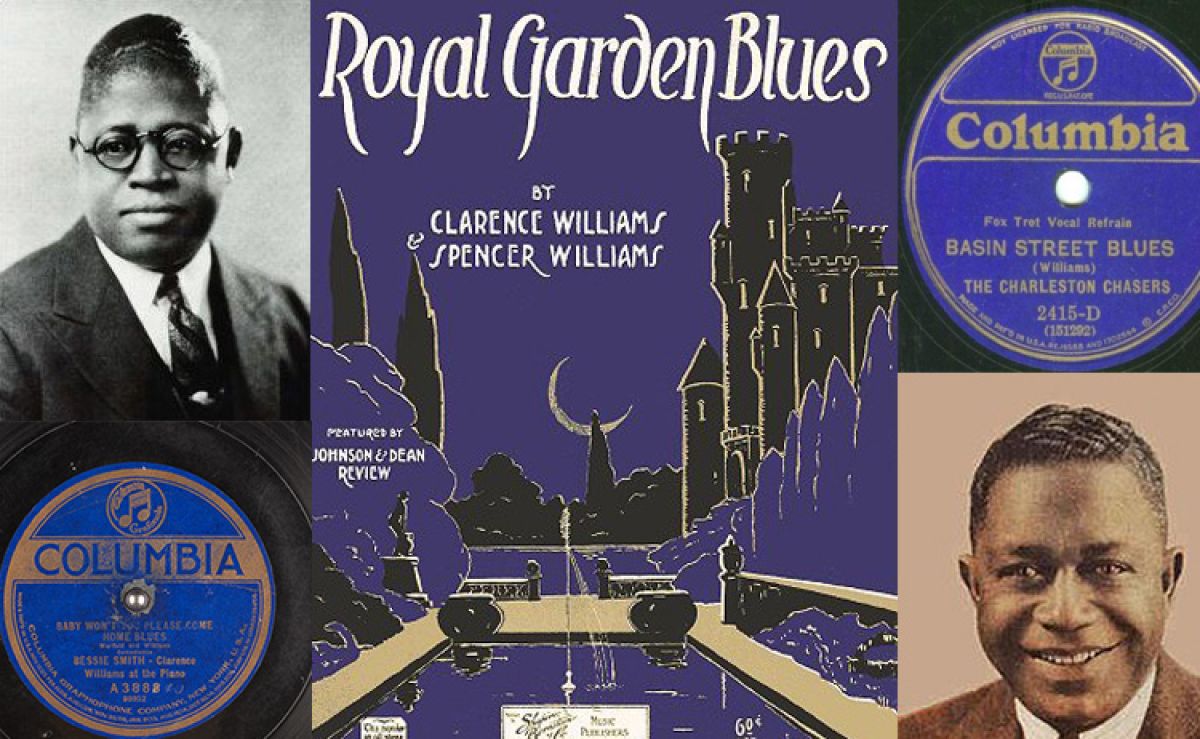

This week on the show, I want to shine my spotlight on two notable jazz and blues songwriters from the 1920s: Clarence Williams and Spencer Williams. They are not related, however, they did both grow up in Louisiana and their paths did cross on several occasions. The two Williams were also responsible for writing some of the biggest jazz and blues standards of the 20th century, like “Basin Street Blues,” “Baby Won’t You Please Come Home” and more. This hour, we’ll explore their life and careers and hear their songs performed by folks like Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and more.

It’s The Two Williams: Clarence and Spencer, coming up next on Afterglow

MUSIC - LOUIS ARMSTRONG, “SQUEEZE ME”

Louis Armstrong and Velma Middleton with “Squeeze Me,” a song co-written by Fats Waller and Clarence Williams. That comes from Louis Armstrong’s 1955 album Satch Plays Fats. “Squeeze Me” was Waller’s second published song, the first being “Wild Cat Blues,” which was first performed in 1923 by Clarence Williams’ Blue Five. Both songs were published by Williams’ publishing company, and Williams was essentially Waller’s manager in the early years. “Squeeze Me” was originally supposed to be “Kiss Me,” a parody of the Victor Herbert waltz called “Kiss Me Again,” but it was updated by Williams to something a little more provocative.

MUSIC CLIP - BIX BEIDERBECKE, “ROYAL GARDEN BLUES”

Mark Chilla here on Afterglow. On this show, we’re exploring the work of Clarence Williams and Spencer Williams, two unrelated, but notable songwriters from New Orleans in the early 20th century.

Let’s start with Clarence Williams. Clarence Williams was born in a small town near Baton Rouge, Louisiana in 1893, and got into the entertainment business at an early age. Before he was a teenager, he ran away from home to join a minstrel troupe in New Orleans, and soon became well-known around town as a vaudeville performer, pianist, and budding music mogul.

In 1915, at age 22, he co-founded a publishing company in order to sell his own songs. It was only the third black-owned music publisher in the entire country at the time. He once claimed that around this time, he was the first person to print the word “jazz” on a piece of sheet music. After some initial success in New Orleans, he moved to Chicago to grow the business. While he was there in the year 1919, he wrote his first big hit song, which you’re hearing right now. It was called “Royal Garden Blues,” which was recorded by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and later became a jazz standard.

The person who helped co-write this tune with him was the other composer in question this hour, Spencer Williams (no relation), a fellow New Orleans musician who had moved to Chicago, who we’ll talk about more in depth later in the hour. It’s thought, perhaps, that Spencer actually wrote the song, and Clarence, as publisher, took some of the credit for rights and royalty reasons. That’s a recurring theme with Clarence Williams—his name is attached to many jazz and blues songs from this period, but there’s some question over the provenance of those songs. He was a skilled promoter, and shrewd businessman as well.

Let’s hear now another song that the two Williams collaborated on in 1919. In this one, Clarence is credited with the music and Spencer with the lyrics.

Here is Louis Armstrong in 1959 with “I Ain’t Gonna Give Nobody None of My Jellyroll,” on Afterglow.

MUSIC - LOUIS ARMSTRONG, “I AIN’T GONNA GIVE NOBODY NONE OF MY JELLYROLL”

Louis Armstrong in 1959 with the Clarence and Spencer Williams song “I Ain’t Gonna Give Nobody None of My Jellyroll,” written in 1919.

Clarence Williams sold the publishing rights to this song around 1920, and used the profits to move out to New York City, where his career really began to take off. His publishing company was now called the “Clarence Williams Music Publishing Company. In 1922, his company started publishing songs that later became standards, like “Tain’t Nobody’s Biz-Ness If I Do.” In 1923, he had a hit with one of his own songs, “Sugar Blues,” which was performed over the decades by several jazz and blues artists.

Here’s Ella Fitzgerald and Her Orchestra in 1940 with that song now. This is “Sugar Blues,” on Afterglow

MUSIC - ELLA FITZGERALD, “SUGAR BLUES”

MUSIC - ELLA FITZGERALD, “GULF COAST BLUES”

Ella Fitzgerald and her Famous Orchestra in 1940 with two songs by Clarence Williams. Just now, we heard “Gulf Coast Blues,” before that “Sugar Blues.”

The original recording of “Gulf Coast Blues” was in 1923 by the legendary blues singer Bessie Smith on a recording for Columbia Records. Let’s take a listen…

MUSIC CLIP - BESSIE SMITH, “GULF COAST BLUES”

It was actually the B-side to her first single ever, “Downhearted Blues.” It was a top pop single and sold over 700,000 copies. A remarkable beginning to her career. The person playing piano in the background of that recording is Clarence Williams.

Not only was Clarence Williams an important publisher and songwriter in the early 1920s, he was also an accomplished musician. He can be heard playing piano on a number of notable recordings from the 1920s (mostly songs that he had a hand in publishing). Some of his most notable work comes from the group known as Clarence Williams’ Blue Five.

The quintet made a series of recordings for Okeh Records in the 1920s, often with Williams’ wife Eva Taylor singing vocals. The group also featured some legendary young jazz talent, including Sidney Bechet who sometimes joined in on clarinet or saxophone, and Louis Armstrong, who was often featured on cornet.

Let’s hear one of those vocal records from Clarence Williams’ Blue Five. This is Clarence Williams on piano, Eva Taylor on vocals, and Louis Armstrong on cornet performing a song written by the other Williams, Spencer Williams, “Everybody Loves My Baby,” on Afterglow

MUSIC - CLARENCE WILLIAMS’ BLUE FIVE - “EVERYBODY LOVES MY BABY”

MUSIC - ETHEL WATERS, “WEST END BLUES”

Ethel Waters and pianist Clarence Williams in 1928 with “West End Blues,” a tune by King Oliver. That song is mostly known as an instrumental—there’s a famous version by Louis Armstrong also in 1928. However, Clarence Williams wrote these lyrics to it, sung here by Waters. Before that, Clarence Williams’ Blue Five in 1924, featuring Louis Armstrong on cornet and Eva Taylor on vocals with “Everybody Loves My Baby,” a song by Spencer Williams.

“Everybody Loves My Baby” became a jazz standard after this 1924 recording for Okeh Records, later sung by Dinah Washington, Pearl Bailey, Jimmy Rushing, and, famously in 1932, the Boswell Sisters. This New Orleans-based trio provided innovative vocal arrangements to a number of songs by both Spencer AND Clarence Williams. Let’s hear another one now, co-written by Clarence Williams, along with fellow African songwriters Tim Brymn and Alex Hill.

This is the Boswell Sisters with “Shout Sister Shout,” on Afterglow.

MUSIC - BOSWELL SISTERS, “SHOUT SISTER SHOUT”

MUSIC - BILLIE HOLIDAY, “SWING BROTHER SWING”

A couple of sibling songs co-written by Clarence Williams. Just now we heard Billie Holiday and the Count Basie Orchestra live at the Savoy Ballroom in New York in 1937 with “Swing Brother Swing,” written by Williams, Lewis Raymond, and Walter Bishop. Before that, “Shout Sister Shout,” performed by the Boswell Sisters and the Dorsey Brothers in New York in 1931.

Clarence Williams continued to write, record, and publish throughout the 1920s and 30s. He starred in the Broadway show Bottomland, created a jazz orchestra in the late 1920s, recorded for the Vocalion and Bluebird labels in the 1930s, and then sold his entire catalog to Decca in the 1940s for a fairly significant chunk of cash. His legacy lives on—not only through his grandson, Mod Squad actor Clarence Williams III, but mostly through his songs.

Let’s hear one of his most famous songs now. He co-wrote this one with songwriter Charles Warfield (although Warfield claims that he wrote it alone). This is Nat King Cole in 1959 with the song “Baby, Won’t You Please Come Home,” on Afterglow.

MUSIC - NAT KING COLE, “BABY, WON’T YOU PLEASE COME HOME”

Nat King Cole and arranger Dave Cavanaugh in 1959 on the album Welcome To The Club with the tune “Baby, Won’t You Please Come Home,” written by Charles Warfield and Clarence Williams.

MUSIC CLIP - LOUIS ARMSTRONG, “WEST END BLUES”

Coming up in just a bit, we’ll explore songs by another notable Williams, Spencer Williams. Stay with us..

I’m Mark Chilla, and you’re listening to Afterglow

MUSIC CLIP - EDDIE CONDON, “I AIN’T GONNA GIVE NOBODY NONE OF THIS JELLYROLL”

MUSIC CLIP - LOUIS ARMSTRONG, “MAHOGANY HALL STOMP”

Welcome back to Afterglow, I’m Mark Chilla. We’ve been exploring the work of two notable black composers from the 1920s this hour, Clarence Williams and Spencer Williams (no relation).

Let’s take a closer look now at songwriter Spencer Williams—not to be confused with actor Spencer Williams Jr., who played Andy on the famous Amos ‘N’ Andy TV. They were also not related!

Records of Spencer Williams’s early years are incredibly spotty. He was born sometime in the late 1880s, either in Louisiana or Alabama. But by his teenage years, we know he settled in New Orleans, where he soaked in the jazz music thriving in that city. One of those places that he heard jazz was likely the infamous Mahogany Hall, a brothel in the Storyville district of New Orleans, run by his aunt, the eccentric Lulu White. That’s Williams’ song “Mahogany Hall Stomp” in the background right now.

While he learned jazz in New Orleans, he found most of his success outside of the Big Easy. He first moved to Chicago around 1907, and then to New York around 1916, where found work as a pianist and songwriter. We’ve already heard a few of the songs he published, often with Clarence Williams, like “Royal Garden Blues,” “I Ain’t Gonna Give Nobody None of My Jellyroll,” and “Everybody Loves My Baby.”

Interestingly, much of Spencer Williams’ success came overseas in Paris and London. He moved to Paris first in 1925, writing music for fellow American expat Josephine Baker at the cabaret Folies Bergère. Many of his songs were first recorded by musicians who flourished in Europe, like saxophonist Benny Carter or singer Elisabeth Welsh.

Here’s a song now, first performed by Carter and Welsh in 1936. This is Sarah Vaughan and guitarist Barney Kessel in 1962 with the Spencer Williams and Benny Carter song, “When Lights Are Low,” on Afterglow.

MUSIC - SARAH VAUGHAN, “WHEN LIGHTS ARE LOW”

MUSIC - THE MILLS BROTHERS, “I’VE FOUND A NEW BABY”

The Mills Brothers in 1934 with “I’ve Found A New Baby,” written by Spencer Williams and Jack Palmer, and first performed by Clarence Williams’ Blue Five back in 1926. Before that, Sarah Vaughan and Barney Kessel in 1962 with the Spencer Williams and Benny Carter song “I’ve Found A New Baby.”

Sometimes trying to uncover the true songwriter of a 1920s composition is a fool’s errand. These were the days when sheet music was king, publishing rights were everything, and music publishers ruled the business. We already talked earlier in the hour about Clarence Williams, who often took co-songwriting credit for many of the songs he published. Did he really weigh in on the songs, or as the person in charge, did he give himself co-writing credit to skim a bit more off the top? It was certainly a common enough practice, and none of us were in the room, so we’ll probably never really know.

Or take a popular song like “I Ain’t Got Nobody.” It’s a catchy enough tune that it became a hit in the 1910s when it was published, in the 1950s when it was sung by Louis Prima, and even the 1980s when it was covered by David Lee Roth. No less than five songwriters lay claim to it. There is Charles Warfield and David Young, who had a copyright on the tune in 1914. Warfield, if you recall, co-wrote “Baby Won’t You Please Come Home” with Clarence Williams in 1922. Then there was Dave Peyton and Spencer Williams who had a copyright on the song in 1915. And then finally in 1916, one publishing company published the Warfield and Young version, and a second published the Williams and Peyton version (although Peyton was replaced with the publishing company’s manager Roger Graham as the primary songwriter).

So did Spencer Williams actually write it? Who knows. Is it a great song? Absolutely. Let’s listen to it now.

Here’s a fun, jazzy version by Sammy Davis Jr. which he recorded way back in 1949 for Capitol Records. This is “I Ain’t Got Nobody,” on Afterglow.

MUSIC - SAMMY DAVIS JR, “I AIN’T GOT NOBODY”

MUSIC - THE BOSWELL SISTERS, “DOWN ON THE DELTA”

The Boswell Sisters and the Dorsey Brothers in 1932 with the song “Down On The Delta,” written by Spencer Williams and Fats Waller. Before that, we heard Sammy Davis Jr. in 1949 with “I Ain’t Got Nobody,” a song often credited to Spencer Williams and Roger Graham.

“Down On The Delta” is a song that looks back fondly at a simple life on the Louisiana delta, a place where songwriter Spencer Williams grew up. Despite spending much of his career traveling around Chicago, New York, Paris, and London, Spencer Williams (and for that matter, Clarence Williams) were raised in New Orleans, the birthplace of jazz, and many of his songs have a nostalgic view Big Easy. In fact, Spencer Williams’ most famous song explores this very topic, calling New Orleans “the land of dreams,” and naming it after the street he grew up on.

Here’s a version of that song in question now from the great Ella Fitzgerald (who channels Louis Armstrong in this recording). This is Ella Fitzgerald in 1950 with “Basin Street Blues,” on Afterglow.

MUSIC - ELLA FITZGERALD, “BASIN STREET BLUES”

Ella Fitzgerald (and her Louis Armstrong impression) in 1950, with the Spencer Williams song “Basin Street Blues.” Thanks for tuning in to this look at the music of Spencer and Clarence Williams, on Afterglow.

MUSIC CLIP - MARIAN MCPARTLAND, “ROYAL GARDEN BLUES”

Afterglow is part of the educational mission of Indiana University and produced by WFIU Public Radio in beautiful Bloomington, Indiana. The executive producer is John Bailey.

Playlists for this and other Afterglow programs are available on our website. That’s at indianapublicmedia.org/afterglow.

I’m Mark Chilla, and join me next week for our mix of Vocal Jazz and popular song from the Great American Songbook, here on Afterglow