[MUSIC CLIP - OSCAR PETERSON, “MOONGLOW”]

MARK CHILLA: Welcome to Afterglow, I’m your host, Mark Chilla.

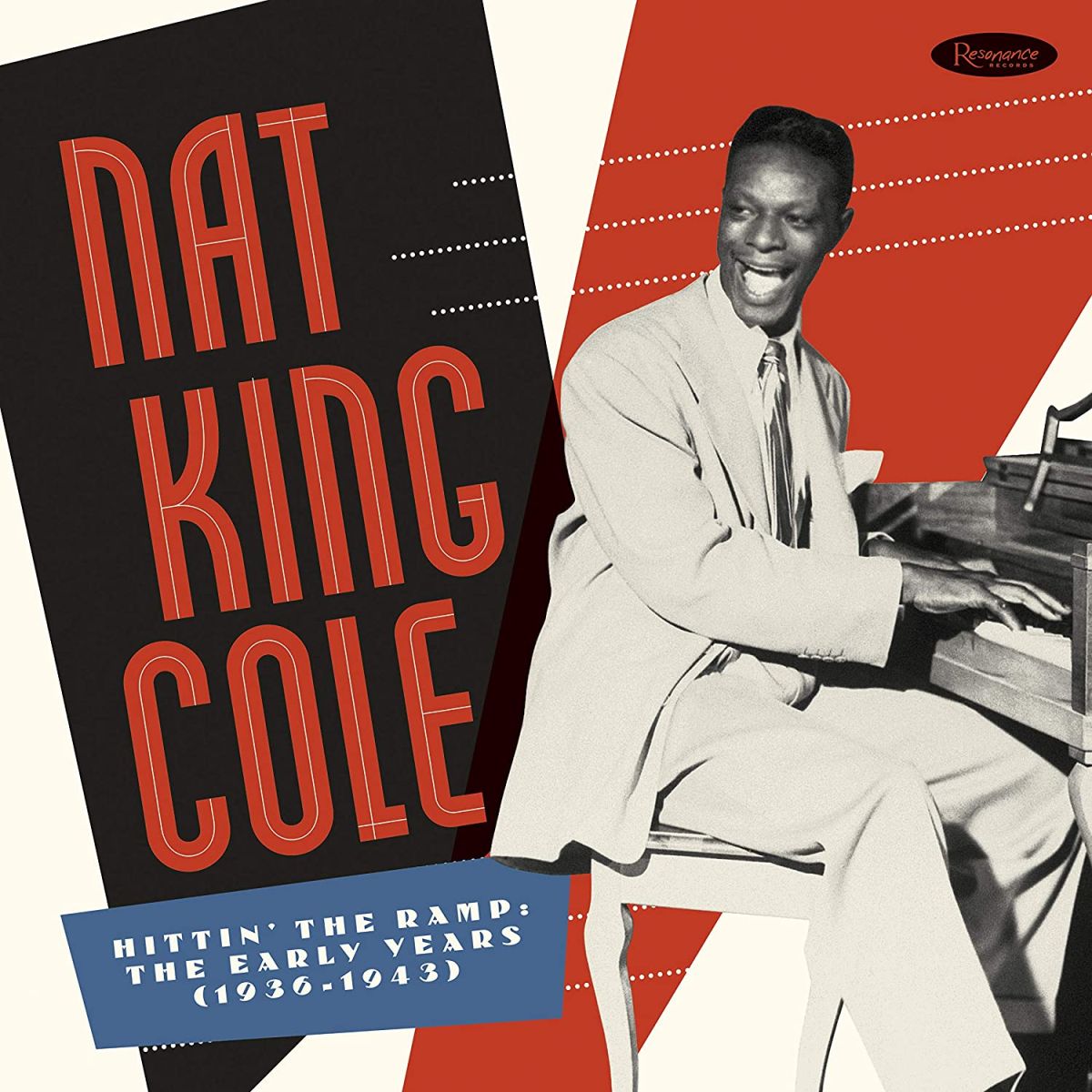

How does a jazz pianist from Chicago become one of the biggest singing stars in Los Angeles? This is the story of the early years for Nat King Cole. In the late 1930s, Cole and his King Cole Trio were developing a new, innovative sound. However, they were recording mostly for radio airplay, rather than for commercial sale. This week, I’ll feature a box set from Resonance Records highlighting these early years for Cole and his trio, and we’ll also hear from jazz historian Will Friedwald, who will provide insight into Cole’s early development.

It’s The King Cole Trio Starts To Swing, coming up next on Afterglow

[MUSIC - KING COLE TRIO, “SWANEE RIVER’]

[MUSIC - KING COLE TRIO, “BY THE RIVER ST. MARIE”]

Two river songs performed by the King Cole Trio in 1938. Just now, we heard “By The River St. Marie,” a song written in 1931 by Harry Warren and Edgar Leslie. Before that, “Swanee River” by Stephen Foster. Both of those recordings were made for the Standard Transcription company.

[MUSIC CLIP - KING COLE TRIO, “B-FLAT”]

MARK CHILLA: Mark Chilla here on Afterglow. On this show, we’re exploring the early years of Nat King Cole, taking a close look at a new box set from Resonance Records called Nat King Cole: Hitting The Ramp, exploring all of his known recordings between 1936 and 1943, just before he signed to Capitol Records.

I also got a chance to talk with one of my favorite jazz historians Will Friedwald over the phone, who is the author of a brand new Nat King Cole biography. Friedwald has written many books about jazz singers, including his 1995 book on Sinatra called The Song Is You. If you’ve ever picked up a Nat King Cole CD, chances are Friedwald wrote the liner notes. His new book, called Nat King Cole: Straighten Up & Fly Right published by Oxford University Press, is sure to become the definitive Cole biography. We’ll hear from Will Friedwald throughout the hour.

Let’s start at the beginning.

[MUSIC CLIP - EARL HINES, “CAVERNISM”]

MARK CHILLA: Nat King Cole was born on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1919, in Montgomery, Alabama. But soon after he was born, Nat’s father (a Baptist preacher) brought the family to Chicago. Many African Americans were moving from the rural south to the urban north during this period known as the Great Migration in order to provide better lives for their families.

Chicago, as it turned out, was a serendipitous place for the Coles to end up. Here’s historian Will Friedwald…

WILL FRIEDWALD: Well, Chicago was, you know, ground zero for the jazz age. It was the expression of black popular music at that point. It was just omnipresent. You couldn’t, you know, be in the street at night and not hear some kind of music, and Nat was part of it. I always say that if their father, who came to Chicago to be a reverend, to preach the holy gospel, if we didn’t want his kids to be musicians, then he came to the worst possible place, because that was just absolutely ground zero for the jazz age. That was where everything was happening. That was the heart of it.

MARK CHILLA: Nat and his older brother Eddie became immersed in the music scene in Chicago. Eddie took up the bass. But for Nat, his love was piano, and he began to absorb the jazz styles all around him. Here’s Friedwald again…

WILL FRIEDWALD: He really just learned from listening and, you know, being an amazing natural talent, you know? In the absence of other evidence you have to say that he just was almost entirely self-taught—or just by hanging around piano players and they showed him how to play this and how to do that, and he picked it up one trick at a time how to do all that. There’s no evidence that he really studied formally or otherwise. He just learned on the job. And he was just a natural musician.

MARK CHILLA: The one piano player that influenced Nat the most was Earl “Fatha” Hines. That’s who you’re hearing in the background right now. Hines had a virtuosic early jazz style that was harmonically complex, and Nat updated it by emphasizing that all-important element of swing.

Even as a teenager, Nat showed tremendous talent, winning contests for his piano playing. Eddie, his brother, left Chicago to tour with noted jazz musician Noble Sissle. But when Eddie learned about Nat’s growing success in Chicago, he came home to form a band. This union eventually led to Nat’s very first recording, made for Decca Records in 1936.

[MUSIC CLIP - EDDIE COLE’S SOLID SWINGERS, “THUNDER”]

MARK CHILLA: The band was called Eddie Cole’s Solid Swingers. Although, Nat was really the de facto leader.

WILL FRIEDWALD: Well, the band came out of Eddie’s name. But as we know, it was really Nat’s band. And they were playing a club called the Panama Cafe, and they got a lot of great press notices, enthusiastic reviews in the local black press. And J. Mayo Williams, who was the head of the Decca Records Sepia Series, the race record series, decided to record them for Decca and they made these four sides. And Nat takes a piano solo in all four of them. You can really hear Nat playing on them—and again he’s 17 years old, but already playing with amazing maturity. Although not as good as he would [play] later on, but still very, very far advanced for a 17-year old.

MARK CHILLA: Let’s hear a bit of that band now from their 1936 session for Decca. This is Eddie Cole’s Solid Swingers, featuring Nat Cole on piano, with Nat’s original song written for Chicago’s Panama Cafe called “Stompin’ At The Panama,” on Afterglow.

[MUSIC - EDDIE COLE’S SOLID SWINGERS, “STOMPIN’ AT THE PANAMA”]

MARK CHILLA: The first recording session featuring Nat Cole. That was him on piano in July 1936 for Decca Records with the band he made with his brother Eddie called Eddie Cole’s Solid Swingers, and Nat’s original song “Stompin’ At The Panama.”

Eddie Cole’s Solid Swingers were not built to last. There was tension between the two brothers, since Nat did most of the work and Eddie took most of the credit. It was made more complicated when an older dancer named Nadine got between them, and fell for the younger brother Nat. The two eventually got married.

[MUSIC CLIP - NOBLE SISSLE, “DEAR OLD SOUTHLAND”]

MARK CHILLA: Their fortunes changed in 1937 when Noble Sissle, Eddie’s old bandleader, came to them with an opportunity. Here is Cole biographer Will Friedwald again.

WILL FRIEDWALD: Noble Sissle, who I mentioned earlier, came back into the life of the Cole brothers when there was a new edition of the show Shuffle Along that was put together, which was, of course, the show that Noble Sissle had written in 1921. It was one of the big—like the most successful show in the history of Black Broadway. It was a real dealbreaker of a show. And they were doing a new edition, even though Noble Sissle wasn’t involved, apparently he was the one who got the producers of the new show to seek out Eddie in terms of somebody to lead a band for the show. But it then wound up that the brothers had this big fight before the show left Chicago. So Eddie stayed in Chicago and Nat went on the road with Shuffle Along, the new edition.

MARK CHILLA: The show took Nat and his new wife Nadine all around the country. However, it folded a few months later shortly after arrived in Los Angeles. So Nat and Nadine made the decision to stay in Los Angeles

WILL FRIEDWALD: Nat always knew exactly what he was doing at every stage. And I think that when he got to California, he thought that this was his chance to, you know, start his own career, and make a fresh start in a whole new part of the world. And I think that he very deliberately wanted to stay in Los Angeles. But the thing about Nat was that he tended to mythologize his own career. And one of the things he said over and over was that every good thing that happened to him was an accident. The fact that he wound up stranded in Los Angeles and started his career there was an accident. The fact that he put together a trio, the famous King Cole Trio, that was an accident. The fact that he started singing, that was an accident. And, you know, Nat was born, as you know, on March 17, 1919, which was St. Patrick’s Day, and he always identified with the Irish. Whenever people would say, “gee, Nat, how come you’re so successful?,” he would attribute it to the “luck o’ the Irish,” and say that he carried a shamrock in his back pocket. But when we really look at what he did and what he achieved and how he did it, it becomes clear that luck had nothing to do with it, that it was a question of good judgment and good timing. And that’s what brought him to California in 1937.

MARK CHILLA: As talented as he was, Nat had no trouble getting work as a pianist. And he did fairly well for himself, too, especially for an 18-year-old kid. Like he did in Chicago, Nat formed a band in Los Angeles, but this time instead of a big band, it was a trio. There’s an old story that says Nat’s new King Cole Trio—featuring Nat on piano, Oscar Moore on guitar, and Wesley Prince on bass—was formed out of necessity. That they were trying to work at a place called the Swanee Inn, but the bandstand was too small to fit more than three players.

[MUSIC CLIP - KING COLE TRIO, “THE BLUE DANUBE”]

MARK CHILLA: Friedwald has a different theory:

WILL FRIEDWALD: I think that what happened was, as we know, his bass player Wesley Prince reminded him of the King Cole fairy tale. He said, you know, we should use “King Cole” as kind of a branding thing, and Nat ran with that idea. And of course King Cole had his fiddlers three. An early billing of the trio, an early advertisements they’re sometimes referred to as the “Jesters Three” or the “Swingsters Three” after “King Cole and his Fiddlers Three.” The idea was to, you know, kind of use that as a branding imperative. And so therefore it had to be a trio. And he decided to have it piano, bass, and guitar because he met this incredible guitar player named Oscar Moore who was just a prodigy. He was to the guitar what Nat was to the piano. And that’s really what the King Cole Trio was based on, the amazing partnership between Nat King Cole and Oscar Moore.

MARK CHILLA: Fairy Tales and Nursery rhymes were not only important for the King Cole Trio’s name, but also for their repertoire. Novelty records based on nursery rhymes or classical melodies made up a significant part of their repertoire. They were familiar and, being in the public domain, they were also cheap. The King Cole Trio was able to revive these numbers with some swing and some virtuosity.

Here’s the King Cole Trio (Nat and his Fiddler’s Three) in 1938 performing some swinging versions of public domain songs now, beginning with “Patty Cake Patty Cake,” on Afterglow.

[MUSIC - THE KING COLE TRIO, “PATTY CAKE, PATTY CAKE”]

[MUSIC - THE KING COLE TRIO, “CHOPSTICKS”]

MARK CHILLA: A couple of public domain novelty numbers by the King Cole Trio. Just now, we heard a vocal version of the familiar piano tune “Chopsticks,” and before that, the nursery rhyme “Patty Cake.”

[MUSIC CLIP - KING COLE TRIO, “VINE STREET JUMP”]

MARK CHILLA: What you heard there was not a commercial recording, but rather a radio transcription, a recording made only for radio play, not for commercial sale. This seemingly counterintuitive practice was actually mandated by both the musician’s union and the record companies. Here’s Will Friedwald…

WILL FRIEDWALD: At that point they thought that if you heard a record on the radio all the time, you would not want to buy it. So, because they couldn’t play commercial recordings on the air, they developed a scheme for which they would record pre-recorded music just for radio play. And there are several whole businesses, companies that sprung up around this idea. And by the time that Nat was starting to, you know, be popular in Los Angeles, this really was a big industry—radio transcriptions. In fact, they were probably comparable to the regular commercial recording industry because during the depression a lot record companies went out of business. Nobody had 35 cents to spend for a record, you know, for 15 cents you could buy a loaf of bread. Surprisingly, unlike the record companies, which were mostly based on the East Coast, a lot of the transcription companies were based in Los Angeles and San Francisco, and they were the first to latch onto Nat. He started recording for them when the trio was only about a year old, around October 1938.

MARK CHILLA: The style of many of these radio transcriptions were not really jazz, either, as you may have noticed. They were basically trio vocal tunes in the style of something that you might have heard from other black pop groups the Ink Spots or the Mills Brothers. Their more overt jazz numbers (and Nat’s emergence as a solo vocalist) came much later. I’ll have more on that later in the hour.

First here is another radio transcription from the King Cole Trio, and a Nat Cole original song too. You’ll hear the trio vocals throughout with a slight nod to jazz improvisation, but staying clearly on the side of pop.

Here is the King Cole Trio in 1939 with “I Like To Riff,” on Afterglow.

[MUSIC - KING COLE TRIO, “I LIKE TO RIFF”]

MARK CHILLA: The King Cole Trio in 1939 with a Nat Cole original song “I Like To Riff.” That recording was made for the Standard Transcription company, exclusively for radio airplay.

[MUSIC CLIP - KING COLE TRIO, “EARLY MORNING BLUES”]

MARK CHILLA: Coming up in just a moment, we’ll hear more from the early years of Nat King Cole. Stay with us. I’m Mark Chilla and you’re listening to Afterglow.

[MUSIC CLIP - KING COLE TRIO, “RIFFIN’ IN F MINOR”]

[MUSIC CLIP - KING COLE TRIO, “ROSETTA”]

MARK CHILLA: Welcome back to Afterglow, I’m Mark Chilla. We’ve been exploring the early years of Nat King Cole and his King Cole Trio, looking at a new box about this time period set from Resonance Records and talking to jazz historian Will Friedwald.

In the late 1930s, the King Cole Trio had yet to be signed to a major label. They were performing live in Los Angeles honing their jazz chops, with the dynamic duo of Cole on piano and Oscar Moore on guitar as the spotlight. They were perfecting their sound on radio as well, recording trio vocal pop records for radio transcription companies like the Standard and MacGregor.

Their reliability as an ensemble also got them work as a backing band. We’re so used to thinking of Cole as a solo vocalist that’s hard to imagine him taking a backseat to another singer. However, the King Cole Trio accompanied both solo singers and vocal groups around 1940.

Let’s hear some of those records now. First, this is a recording from 1939 for the Standard Transcription company featuring the vocal group known as The Dreamers, a group in the style of the Ink Spots or the Delta Rhythm Boys.

This is The Dreamers with the King Cole Trio performing the song “Music’ll Chase Your Blues Away,” on Afterglow.

[MUSIC - KING COLE TRIO WITH THE DREAMERS, "MUSIC’LL CHASE YOUR BLUES AWAY"]

[MUSIC - KING COLE TRIO WITH ANITA BOYER, "WHATCHA KNOW, JOE?"]

MARK CHILLA: The King Cole Trio with big band singer Anita Boyer performing the “Trummy” Young song “Whatcha Know, Joe?.” That recording was made for the MacGregor transcription company in 1941. Before that, we heard the King Cole Trio accompanying the vocal group The Dreamers in 1939 with the song “Music’ll Chase Your Blues Away.”

[MUSIC CLIP - KING COLE TRIO, "THE LAND OF MAKE BELIEVE"]

MARK CHILLA: These radio transcriptions, as we’ve discussed, were not made available for commercial sale. The King Cole Trio was signed to Decca Records in 1941 and cut their first commercial recordings—however other recordings that they made before that happened to be sold without their knowledge. Here’s Nat Cole biographer and jazz historian Will Friedwald…

WILL FRIEDWALD: Before that, they had done some transcriptions for a company called Davis & Schwegler. The company wound up pressing them as 78s and selling them as 78s. I don’t know how many copies they sold, or where they were sold, but it was very, very small distribution. And then, he also made some recordings for a company that was only distributing to jukeboxes, and that was Ammor Records in 1940.

[MUSIC CLIP - KING COLE TRIO, “BLACK SPIDER STOMP”]

WILL FRIEDWALD: And that’s an interesting session, for some reason they added a drummer to it who completely louses it up. But then the jukebox company went out of business and they sold it to Varsity, who then issued it and sold it again to Savoy, and that was an early commercial record that was issued, I think, in like August 1940. But I would contend that when Nat did those dates, he did not think they were gonna be sold commercially. The first time he actually went into a studio and knew it was going to be a record that was for sale to the public was the first of the Decca sessions, which was done in Los Angeles. Then he did one in Chicago and two in New York.

MARK CHILLA: Those early Decca recording sessions also show Nat King Cole flourishing as a solo vocalist. As early as 1938, Cole was more or less the “lead” vocalist of the King Cole Trio. You can hear him taking solos, even as the trio emphasized group singing.

[MUSIC CLIP - KING COLE TRIO, “DARK RAPTURE”]

MARK CHILLA: However, it was around 1940, as more people began to take notice of Nat’s singing voice, that his solo recordings began to take shape. The central song to his development as a singer was the Cliff Burwell and Mitchell Parish song “Sweet Lorraine.”

[MUSIC CLIP - NAT KING COLE AND DEXTER GORDON, “SWEET LORRAINE”]

MARK CHILLA: Here’s jazz historian Will Friedwald…

WILL FRIEDWALD: There’s a famous story that Nat told that some drunk in the audience wouldn’t let him alone until he sang “Sweet Lorraine.” And for all I know that might have happened. But the more likely scenario was that Nat was always willing to try something new, and when he saw that people were responding to his solo vocals—and more importantly to his ballad vocals, the idea that he could sing a love song, something like “Sweet Lorraine”—was a big step. There’s a cute story that when he played New York for the first time, he was really, really trying to sing, and the song that he was concentrating on was “Sweet Lorraine.” And he would get to the club in the middle of the afternoon and he would just rehearse “Sweet Lorraine” over and over and over. And finally the bookkeeper who was sitting there, hearing Nat Cole sing “Sweet Lorraine” like 50 times, she called the boss and said, “You gotta get this guy to stop, or to sing something else! He’s driving me crazy with that “Sweet Lorraine.” And the club owner said, “No, you gotta be mistaken! Nat doesn’t sing. It’s gotta be somebody—you know, Nat couldn’t be singing!”

MARK CHILLA: I’ll play for you now a few of those early Decca sides, beginning with the ballad in question. This is Nat King Cole and his King Cole Trio in December 1940 with the song “Sweet Lorraine,” on Afterglow.

[MUSIC - KING COLE TRIO, “SWEET LORRAINE]

[MUSIC - KING COLE TRIO, “HIT THAT JIVE JACK”]

MARK CHILLA: Nat King Cole and the King Cole Trio with two of their first singles for Decca Records. Just now, we heard “Hit That Jive, Jack,” recorded in New York in 1941. Before that, his signature song “Sweet Lorraine,” recorded in Hollywood in 1940

The King Cole Trio did not stay signed to Decca for long. World War II had caused many record labels to cut back on resources, so the label decided that it couldn’t support more than one black pop group. Decca put their support behind their more established act Louis Jordan and his Tympany Five, cutting the younger King Cole Trio loose.

[MUSIC CLIP - KING COLE TRIO, “HIT THE RAMP”]

MARK CHILLA: However, Cole and the trio had other tricks up their sleeve. Here’s jazz historian Will Friedwald:

WILL FRIEDWALD: They got to the point where they became much more of a serious jazz group by like 1940. They were playing many more instrumentals, more extended improvisations. I mean, you have two jazz virtuosos—that’s kind of an obvious decision. And interestingly enough, that’s when the white press and the jazz press—and jazz fans, white jazz fans—first discovered Nat, was around 1940. And that’s what they thought Nat was coming from. They didn’t realize he had a whole other side to him that was more pop oriented. But that sort of started this thing, that, when Nat started to go back in a pop direction later on, a lot of them accused him of deserting jazz and stuff like that. Which really wasn’t true, he had been making pop music from the very beginning!

MARK CHILLA: Jazz became a focus for the group in the early 1940s. And much of this was the result of a chance meeting with a young, white, aspiring record producer named Norman Granz. Granz would later become the founder of Verve Records and the successful Jazz At The Philharmonic Concert Series, but before he met Nat, he was just a jazz fan. They were both based out of Los Angeles, however they met in New York while Nat was performing at a club called Kelly’s Stable and Granz was on leave from the army. Here’s Friedwald again

WILL FRIEDWALD: Nat played something like 9 months on-and-off in New York at Kelly’s Stable, and Norman heard him and just was blown away, thought he was one of the greatest piano players he had ever heard. Correctly so, he was! And he and Norman became very famous friends. And later on Norman became a hugely successful producer of jazz recordings and concerts, and he always gave credit to Nat as being his first African-American friend, and his first friend in the community of musicians, and the first guy who really gave him an entry, a passport, into the world of musicians that enabled him to do things like start Verve Records and start the famous Jazz at the Philharmonic concert series. And he was able to do all of that because Nat really brought him into that world. And he said in turn that he thinks that he was the first white person that really got close to Nat.

MARK CHILLA: Back in L.A., Nat and Norman began to organize Sunday night jam sessions. Norman collected the money and Nat organized the band, drawing upon all of the musicians who made their way through the West Coast. This “jam session” was ultimately the impetus for the Jazz at the Philharmonic concert series in the 1940s.

[MUSIC - NAT KING COLE AND LESTER YOUNG, “I CAN’T STARTED”]

MARK CHILLA: Cole was also present for Granz’s first recording sessions as a producer, which became one of the most legendary recording sessions among hardcore jazz fans. It featured Nat Cole on piano and the legendary Lester Young on saxophone performing in a freer style than anyone was used to hearing on record. Here’s Friedwald again…

WILL FRIEDWALD: Oh, that was a direct outgrowth of the early jam sessions they did. I think actually Lester Young was not part of Basie at that point, Lester was in town. He was based in Los Angeles and he was a frequent participant in the Nat/Norman jam sessions. And obviously he was the most—you know, along with Coleman Hawkins—the most famous saxophone player of that period. And he was a natural partner with Nat. And it was Norman’s genius move to record the two of them together. And even though he insisted that they make these extra long records, which really he had a hard time releasing because of the technology of the day. They’re all like 4 minutes long. They could not be distributed through normal channels, so really only cognoscenti knew about them for many, many years. They weren’t available on LP until at least 10, 15 years afterwards. And they’re really not structured like big band records, or anything like that. They really are just a piano player—a great piano player and a great saxophone player just stretching out. And they’re just beautiful. They are just two just two master musicians let loose.

[MUSIC (CONTINUED) - Nat King Cole and Lester Young, “I Can’t Get Started”]

MARK CHILLA: The Vernon Duke song “I Can’t Get Started” performed there by pianist Nat King Cole and tenor saxophonist Lester Young. That comes from a legendary jazz session recorded in July 1942 and produced by Norman Granz.

1943 was a pivotal year for Nat Cole. That year he acquired a new manager Carlos Gastel, who helped guide his career for the next decade. And that same year, he and the trio signed to Capitol Records, a brand new label formed in Los Angeles by music shop owner Glenn Wallichs and songwriters Johnny Mercer and Buddy DeSylva. Over the next 10 years, Cole would sell over 15 million records for Capitol, and the label later gave their iconic downtown L.A. headquarters the name “The House That Nat Built.”

[MUSIC CLIP - NAT KING COLE, “STRAIGHTEN UP AND FLY RIGHT”]

MARK CHILLA: His first hit for Capitol was a song that he wrote earlier that year based on an old sermon his father used to give. It was called “Straighten Up and Fly Right.” Not only did the song help make Nat a star, but it also taught him a valuable lesson. Here’s Cole biographer Will Friedwald again…

WILL FRIEDWALD: There’s a famous story that after he wrote “Straighten Up And Fly Right,” the publisher gave him $50 and that was it. But Nat never let that happen to him again. After a few years, he started his own publishing company, and then when he found “Nature Boy,” the song “Nature Boy” came to him, he published it himself.

[MUSIC CLIP - NAT KING COLE, “NATURE BOY”]

WILL FRIEDWALD: And so, he was able to reap the benefits of a lot of things, like business-wise. You know, you always hear about famous black jazz musicians and famous black R&B musicians who got ripped off by a greedy system, got taken advantage of… except for “Straighten Up And Fly Right,” that never happened to Nat. He always was in too much control to ever let anybody put one over on him.

MARK CHILLA: To close off this hour, I’m going to play what’s believed to be the first recording of “Straighten Up And Fly Right,” recorded in the summer of 1943, months before the Capitol single. This recording is featured on the new box set from Resonance Records called Nat King Cole Hittin’ The Ramp: The Early Years 1936–1943.

It comes from a broadcast on the Armed Forces Radio Service “Jubilee” program, a radio program produced for African American GIs serving in World War II. You’ll hear that they were still working out the arrangement in this recording, and the introduction is different from the Capitol single.

Here’s Nat King Cole and the King Cole Trio on the radio in 1943 with “Straighten Up And Fly Right,” on Afterglow.

[MUSIC - NAT KING COLE, “STRAIGHTEN UP AND FLY RIGHT (LIVE)”]

MARK CHILLA: Nat King Cole and the King Cole Trio in 1943 with Cole’s original song “Straighten Up and Fly Right.” That comes from a performance on the Armed Forces Radio Service “Jubilee” program, months before the “Straighten Up and Fly Right” single was released for Capitol Records.

[MUSIC CLIP - NAT KING COLE AND LESTER YOUNG, “INDIANA”]

MARK CHILLA: Special thanks go out this week to the folks at Resonance Records for producing the brand new box set Nat King Cole Hittin’ The Ramp: The Early Years 1936–1943, where most of these recordings this hour came from.

And my thanks also go out to jazz historian Will Friedwald, for taking the time to talk with me about Nat King Cole. His new biography is called Straighten Up and Fly Right: The Life and Music of Nat King Cole, published by Oxford University Press.

Thanks for tuning in to this Nat King Cole edition of Afterglow.

Afterglow is part of the educational mission of Indiana University and produced by WFIU Public Radio in beautiful Bloomington, Indiana. The executive producer is John Bailey.

Playlists for this and other Afterglow programs are available on our website. That’s at indianapublicmedia.org/afterglow.

I’m Mark Chilla, and join me next week for our mix of Vocal Jazz and popular song from the Great American Songbook, here on Afterglow