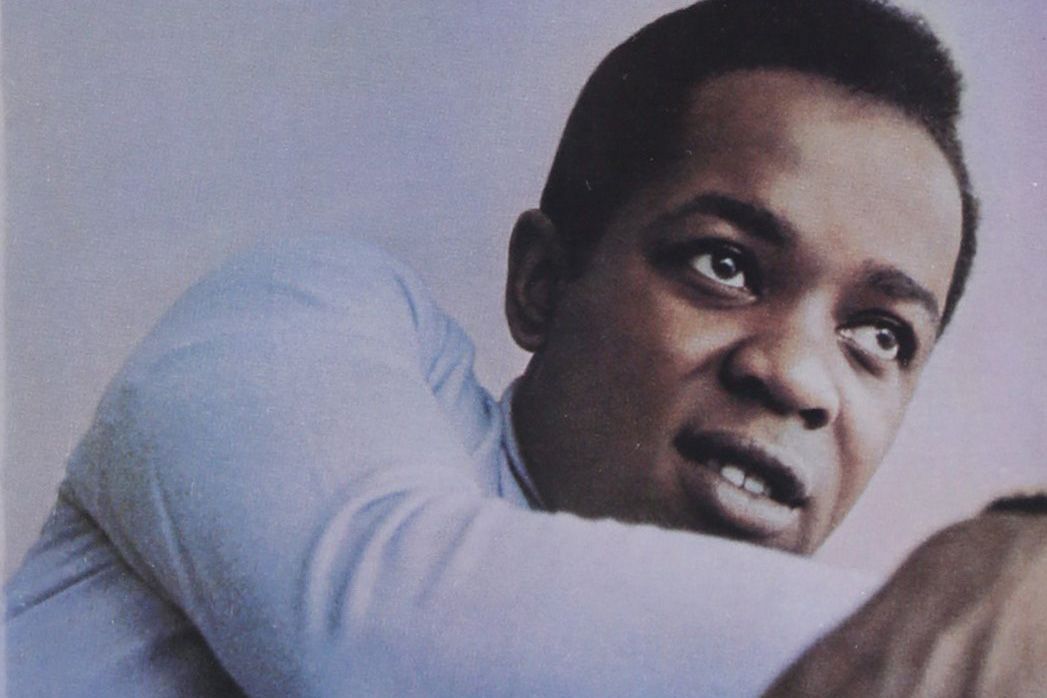

Lou Rawls recorded gospel, jazz, blues, R&B and pop for Capitol Records in the 1960s.

On this show, I turn the spotlight onto an iconic singer of 20th century music: Lou Rawls. Rawls was a gospel singer turned R&B crooner, whose rich baritone could evoke soul, jazz, and the blues. This hour, I’ll explore some of blues and jazz recordings Lou Rawls made in the 1960s while recording for Capitol Records, including such iconic songs as “Tobacco Road,” “I’d Rather Drink Muddy Water,” and “Nobody But Me.”

Lou and Sam

You can’t talk about Lou Rawls without first talking about Sam Cooke.

Their fates were tied together in the late 1950s. Rawls was three years younger than Cooke, and follow closely in his footsteps. They both grew up in the gospel scene in Chicago, and sang in different gospel quartets in their youth. Rawls even replaced Cooke as in the group the Highway QC’s when Cooke joined the Soul Stirrers in the 1951. Rawls however made a name for himself in the gospel group The Pilgrim Travelers.

In 1958, Rawls and Cooke bonded even further when they both nearly died in car crash while on tour together in the south. In the early 1960s, Rawls followed in Cooke’s footsteps again by leaving the gospel world and trying his hand at becoming a pop singer, just like Cooke. In 1962, when Sam Cooke recorded his next pop hit “Bring It On Home To Me,” it was Lou Rawls who sang background vocals.

This helped make Lou Rawls an artist to watch. The same year, he was signed to Capitol Records. He was 29 years old with a rich, sultry baritone, very different from the light and sweet tenor that made Cooke a star. But like Cooke, Rawls was capable of performing soul, blues, jazz, and R&B. On his first album for Capitol in 1962, he does a little bit of each.

Stormy Monday

His first album was called Stormy Monday and featured soul jazz pianist Les McCann as the bandleader. On the album, Rawls performs jazz standards like “Willow Weep For Me” and “God Bless The Child.” These songs were originally performed by Billie Holiday, and both Rawls and Cooke were influenced by the late jazz singer. Cooke even recorded a tribute album to Holiday in 1959.

At the same time, Rawls performs R&B standards like “I’d Rather Drink Muddy Water” and “In The Evening When The Sun Goes Down,” as well as blues songs like “T’Aint Nobody’s Business” and “See See Rider.” It’s a remarkable major label debut that’s mature, tasteful and soulful. There are traces of Joe Williams, Arthur Prysock and Dinah Washington in his voice.

His follow-up for the Capitol label was recorded later that year. This album was a true gospel record to showcase Rawls’s roots. It was called The Soul-Stirring Gospel Sounds of the Pilgrim Travelers, pairing Rawls up with his old gospel pals.

Onzy Matthews

Rawls had a busy 1962. After Stormy Monday and The Soul-Stirring Gospel Sounds, he recorded a more straight-ahead jazz blues record called Black and Blue with arranger Onzy Matthews. Matthews who was beginning to make a name for himself in the jazz-soul crossover market and would later record with folks like Ray Charles.

The album features a number of jazz and blues standards, including “Trouble In Mind” and a big band version of “I’d Rather Drink Muddy Water.” This new version is more rollicking than the small ensemble version Rawls recorded with McCann on Stormy Monday.

Rawls’s follow up album to Black and Blue was Tobacco Road, another album he made with arranger Onzy Matthews. The album featured a mix of blues and jazz standards like “Ol Man River,” “Stormy Weather” and “St Louis Blues,” plus a few newer songs like the title track “Tobacco Road.”

Rawls didn’t write “Tobacco Road”—it was written by John D. Loudermilk, who recorded it in 1960 as a country blues song. Loudermilk, a white man, wrote it about his life growing up poor near the tobacco fields of North Carolina. But Rawls turned it into a soul blues song, and an anthem for black poverty in America. That song later became a signature staple of Rawls’s live sets.

Chicago Blues, H.B. Barnum, and Lou Rawls Live!

In the mid 1960s, Capitol Records began experimenting with Lou Rawls’s sound. One direction they took him in was towards an electric, Chicago blues sound, in the style of Freddie King, Otis Rush, or B.B. King. His 1966 album Carryin’ On featured him with a basic blues band of electric guitars, piano, bass and drums. Rawls, as always, easily adapts to the style.

Lou Rawls’ next big collaborator in the 1960s was arranger H. B. Barnum. Barnum was younger than Rawls, but had more experience in show business than him, as a singer, songwriter, arranger, and former child actor. Barnum created a band for Rawls that functioned somewhere between and R&B band and a jazz big band, featuring trumpets, saxophones, piano, bass, guitar and drums. It was a lean and versatile ensemble that could slide between genres easily, much like Rawls himself. The two worked together on the albums Soulin’ in 1966 and Too Much in 1967.

One of the most interesting songs he recorded in the decade was the tune “Let’s Burn Down The Cornfield,” written by Randy Newman and first recorded by Lee Hazelwood. Like he demonstrated with “Tobacco Road,” Rawls’s performance of this former pop/country song showcases his ability to turn almost any song into a black anthem.

His most successful experiment with Capitol Records in the 1960s was the 1966 album Lou Rawls Live! The album truly highlights his excellence as a performer and was a triumph for the singer when it was released, earning lots of radio play. Lou Rawls Live! was recorded in studio before a live audience of friends, and features some favorites like “Tobacco Road,” “Stormy Monday,” and “I’d Rather Drink Muddy Water.” More than anything, the album showcases Rawls’s storytelling and his incredible ability to express the soulful feeling in a tune, communicating with an audience like few other artists could do.

Rawls Goes Pop

Over the course of the decade, Rawls would creep ever more closely to the world of pop. He had a minor with with “Love Is A Hurtin’ Thing” in 1966. The song is heavy on the horns with a polished sheen that gives it the sound of mid-60s Burt Bacharach with a hint of Motown.

Another pop hit for Rawls was “Nobody But Me,” although this song has more hints of blues. “Nobody But Me” has the same kind of walking, descending bass line as the song “Fever” by Peggy Lee. That song was featured on the 1964 album Nobody But Lou.

Towards the end of the 1960s, Rawls continued to make appearances in the pop charts. In 1969, his version of the song “Your Good Thing (Is About To End)” reached number 18 on the Billboard chart, marking his second entry into the top 20 after “Love Is A Hurtin’ Thing.”

By the 1970s, Rawls had put most of jazz behind him to focus solely on pop and R&B, becoming an icon in the genre with songs like “You’ll Never Find Another Love like Mine” in 1976.