MUSIC CLIP - OSCAR PETERSON, “MOONGLOW”

Welcome to Afterglow, a show of vocal jazz and popular song from the Great American Songbook. I’m your host, Mark Chilla.

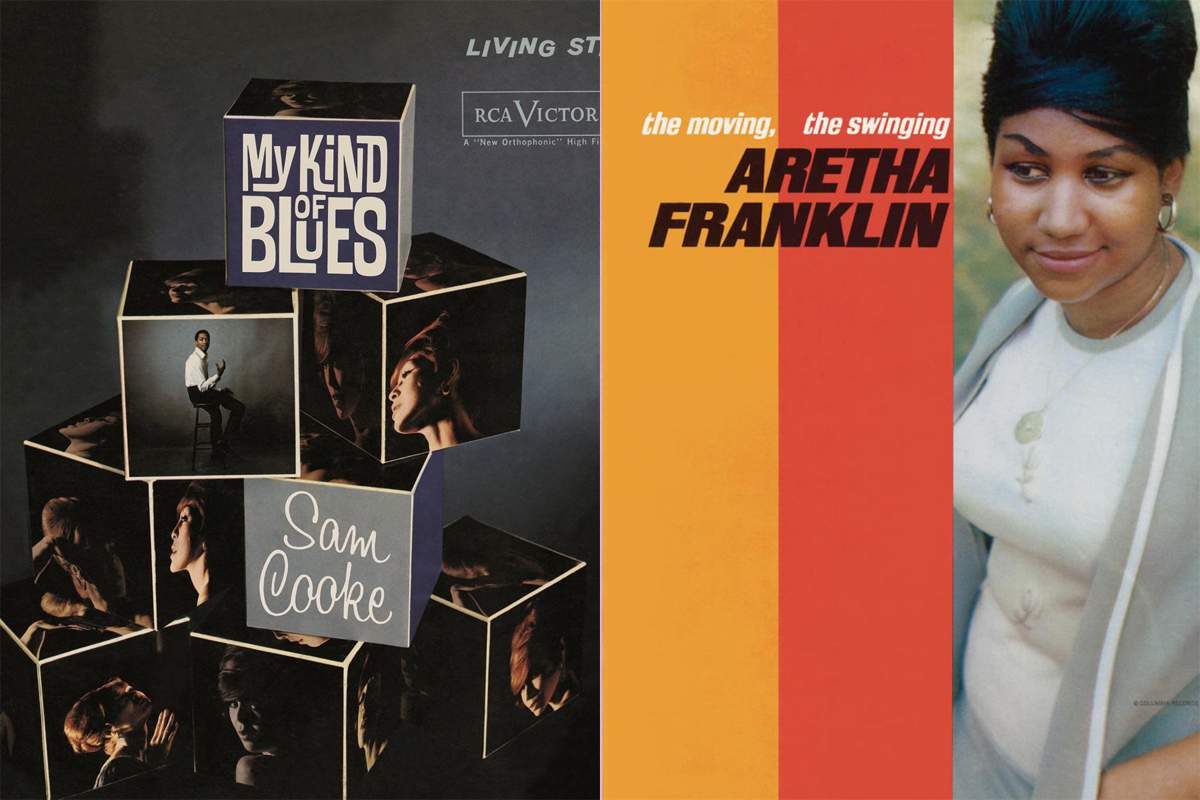

We’re continuing our celebration of African-American Music Appreciation Month by exploring two venerated names in the world of soul: Aretha Franklin and Sam Cooke. Both were children of Baptist preachers who both began their musical careers singing gospel, Cooke and Franklin are known for taking that gospel sound and transforming the world of rock and R&B. But each artist, at one point or another in their career, also interpreted the music of the Great American Songbook, and that’s what we’re exploring in this episode.

It’s The King and Queen of Soul Sing Standards, coming up on Afterglow

MUSIC - ARETHA FRANKLIN, "SOLITUDE"

Duke Ellington, Irving Mills, and Eddie DeLange’s song “Solitude” from Aretha Franklin’s 1962 Columbia release Laughing on the Outside. This standard “Solitude” was a signature tune for Billie Holiday. And when Sam Cooke released his Billie Holiday tribute album for the Keen label in 1969, which was called Tribute to the Lady, he also included this song.

MUSIC CLIP - SAM COOKE, "SOLITUDE"

MUSIC CLIP - JACK MCDUFF, "A CHANGE IS GONNA COME"

Mark Chilla here on Afterglow. On this show, we turn the spotlight on two soul legends—Sam Cooke and Aretha Franklin—who each, at one point in their career, interpreted the standards of the American Songbook.

Cooke was 10 years older than Franklin, but their careers had very similar arcs. Each grew up as the child of a Baptist preacher, singing gospel music in church. Cooke was from Chicago, Franklin from Detroit—Cooke’s professional music career started when he was teenager at age 19, after joining the hugely popular gospel group The Soul Stirrers as their new lead singer.

MUSIC CLIP- SAM COOKE & THE SOUL STIRRERS, "JESUS GAVE ME WATER"

Franklin also recorded her first gospel record while she was just a teenager, at age 14.

MUSIC CLIP - ARETHA FRANKLIN, "THERE IS A FOUNTAIN FILLED WITH BLOOD"

We’ll start with Sam Cooke. He officially “crossed over” from gospel to pop in 1957, signing with the Keen label and earning a hit with his own song “You Send Me.”

MUSIC CLIP - SAM COOKE, "YOU SEND ME"

And even though he became a superstar in the youth pop market and had already been a star on the gospel circuit, Cooke’s eye was clearly on the music of the American Songbook. Standards like “Ol’ Man River,” “Moonlight In Vermont,” “Accentuate The Positive,” and “I Cover The Waterfront” show up on his first LPs for Keen in the late 1950s—many of which are hard to find on reissue today. He was following in the footsteps of his idols Billy Eckstine and Nat King Cole, preferring the Copacabana over American Bandstand.

Let’s hear some early standards from Cooke. First, here’s Sam Cooke in 1958 with “Summertime,” on Afterglow.

MUSIC - SAM COOKE, "SUMMERTIME"

MUSIC - SAM COOKE, "DON'T GET AROUND MUCH ANYMORE"

MUSIC - SAM COOKE, "LITTLE GIRL BLUE"

Sam Cooke with a few jazz standards. Just now, Rodgers and Hart’s “Little Girl Blue” and Duke Ellington’s “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” both from his 1961 album My Kind Of Blues. Before that, Gershwin’s “Summertime” from his debut album in 1958.

RCA records wasn’t sure how to market Sam Cooke when he first started recording—he was showing success as a pop singer among teens, but Cooke also showed desire to create more adult oriented pop, in the style of Billy Eckstine or Frank Sinatra.

Aretha Franklin’s foray into the world of standards and traditional pop also comes from record executives unsure of how to market her. Most of us know Franklin’s soulful songs for Atlantic Records from the late 1960s, like “Respect” or “Chain of Fools.” But before that, Franklin released nine albums for Columbia records over 6 years, all of which were more in a jazz-pop style.

Franklin couldn’t hide her gospel roots in her voice, which is why she shined so much in the R&B records for Atlantic. But she was such a versatile singer that while on Columbia, she could at times sound like jazz singers Dinah Washington or even like Sarah Vaughan, as she does on this next track.

Here’s Aretha Franklin in 1965 with Errol Garner’s “Misty,” on Afterglow.

MUSIC - ARETHA FRANKLIN, "MISTY"

MUSIC - ARETHA FRANKLIN , "LOVE FOR SALE"

MUSIC - ARETHA FRANKLIN, "SKYLARK"

Aretha Franklin with her own fantastic rendition of Hoagy Carmichael and Johnny Mercer’s “Skylark.” That’s originally from the 1963 album Laughing on the Outside. Before that, we heard Franklin doing her best Dinah Washington impression on Cole Porter’s “Love for Sale,” and doing her best Sarah Vaughan impression on Errol Garner’s “Misty.” Both of those tracks are from the remastered reissue of her 1965 album Yeah!!! for Columbia Records.

We’re exploring the music of two soul superstars Aretha Franklin and Sam Cooke on this show, looking at the times they sang standards. I always find it fascinating to hear two artists interpret the same standard—the comparison allows you to really understand what makes each artist an individual. Let’s do that now with the old Richard M. Jones blues standard “Trouble in Mind,” a song sung in the past by Louis Armstrong, Nina Simone, and Dinah Washington. Sam Cooke’s version is classic Cooke from this era: a light swing, his gorgeous tenor vocals effortlessly gliding through the tune with those typical Sam Cooke ornaments. The cheerfulness in his voice really emphasizes the optimism of the song, making you believe that the sun is going to shine in his backdoor someday. Aretha on the other hand is in full preacher mode, turning it into a raucous gospel revival number.

First, here’s Sam Cooke in 1961 with “Trouble in Mind,” on Afterglow.

MUSIC - SAM COOKE, "TROUBLE IN MIND"

MUSIC - ARETHA FRANKLIN, "TROUBLE IN MIND"

Two versions of the old blues standard “Trouble in Mind,” by Aretha Franklin in 1962 and Sam Cooke in 1961. We’ll hear more standards from both of these artists after a quick break. Stay with us.

MUSIC CLIP - RED GARLAND, "TROUBLE IN MIND"

I’m Mark Chilla, and you’re listening to Afterglow

MUSIC CLIP - MIKE LEDONNE AND THE GROOVE QUARTET, "YOU SEND ME"

MUSIC CLIP - JIMMY SMITH, "RESPECT"

Welcome back to Afterglow, I’m Mark Chilla. So far this hour, we’ve been looking at standards from the American Songbook as performed by two soul legends: Sam Cooke and Aretha Franklin.

Aretha Franklin recorded most of her standards while signed to the Columbia label in the early 1960s. Evidently, before she signed to Columbia, Sam Cooke of all people was fighting to get her to sign to his label RCA. But the legendary A&R man for Columbia, John Hammond, was able to entice her. Hammond was the same man who discovered Billie Holiday, and he wanted to market Aretha as the next jazz sensation.

We’ll start this set with a standard from 1932 that was transformed in 1966 by another soul legend, Mr. Otis Redding. The song “Try a Little Tenderness” also has the distinction of being a song Aretha Franklin performed on her very first appearance on American Bandstand in 1962.

From the album The Tender, The Moving, The Swinging Aretha Franklin, here’s Aretha Franklin’s tender and moving version of “Try a Little Tenderness,” on Afterglow.

MUSIC - ARETHA FRANKLIN, "TRY A LITTLE TENDERNESS"

MUSIC - ARETHA FRANKLIN, "WHAT A DIFF'RENCE A DAY MAKES"

Aretha Franklin with the standard “What a Diff’rence a Day Made,” a song first made famous by Dinah Washington That comes from her 1964 album Unforgettable: A Tribute to Dinah Washington. Before that, Franklin in 1962 with the 1932 jazz standard “Try A Little Tenderness.”

We’re listening this hour to standards performed by two of the biggest names in soul music, and we’ll hear some more now from Sam Cooke from his 1963 album Mr. Soul. In just a moment we’ll hear Cooke’s take of “These Foolish Things Remind Me Of You” an American jazz standard that actually has its origins in England.

But first, let’s hear a song first made famous by Julie London in 1955. Here’s Sam Cooke in 1963 with “Cry Me a River,” on Afterglow.

MUSIC - SAM COOKE, "CRY ME A RIVER"

MUSIC - SAM COOKE, "THESE FOOLISH THINGS"

From the 1963 RCA album Mr Soul, we just heard Sam Cooke with two standards, “These Foolish Things,” and before that “Cry Me a River.”

In 1967, Aretha Franklin had made the move from Columbia Records to Atlantic Records. And with that came a change in her style. Atlantic encouraged her to be an R&B, and so the songs she started performing were more contemporary pop and R&B hits, rather than songbook standards. She only recorded jazz era songs a handful of times after that year. Of course, by 1967, Sam Cooke was not recording at all. He was tragically shot in 1964, and died at the young age of only 33.

To close off this week’s show let’s hear two more well-known standards, one each from Aretha and Sam. Both of these songs also both happen to be songs made famous by Billie Holiday. We’ll start with one of Franklin’s only post-1967 standards.

This is Aretha Franklin in 1969 performing the 1949 jazz standard “Crazy He Calls Me,” on Afterglow.

MUSIC - ARETHA FRANKLIN, "CRAZY HE CALLS ME"

MUSIC - SAM COOKE, "LOVER, COME BACK TO ME"

Sam Cooke in 1959 from his Billie Holiday tribute album with the jazz standard “Lover Come Back To Me.” Before that, Aretha Franklin in 1969 with a song first made famous by Billie Holiday, the tune “Crazy He Calls Me.”

And thanks for tuning in to this King and Queen of Soul Sing Standards edition of Afterglow.

[Next week on the show, we’ll be continue our celebration of African American Music Appreciation Month by looking at another soul artist who sang standards: Marvin Gaye. I hope you’ll tune in].

MUSIC CLIP - ARETHA FRANKLIN, "HARD TIMES (NO ONE KNOWS BETTER THAN I)"

Afterglow is part of the educational mission of Indiana University and produced by WFIU Public Radio in beautiful Bloomington, Indiana. The executive producer is John Bailey.

Playlists for this and other Afterglow programs are available on our website. That’s at indianapublicmedia.org/afterglow.

I’m Mark Chilla, and join me next week for our mix of Vocal Jazz and popular song from the Great American Songbook, here on Afterglow