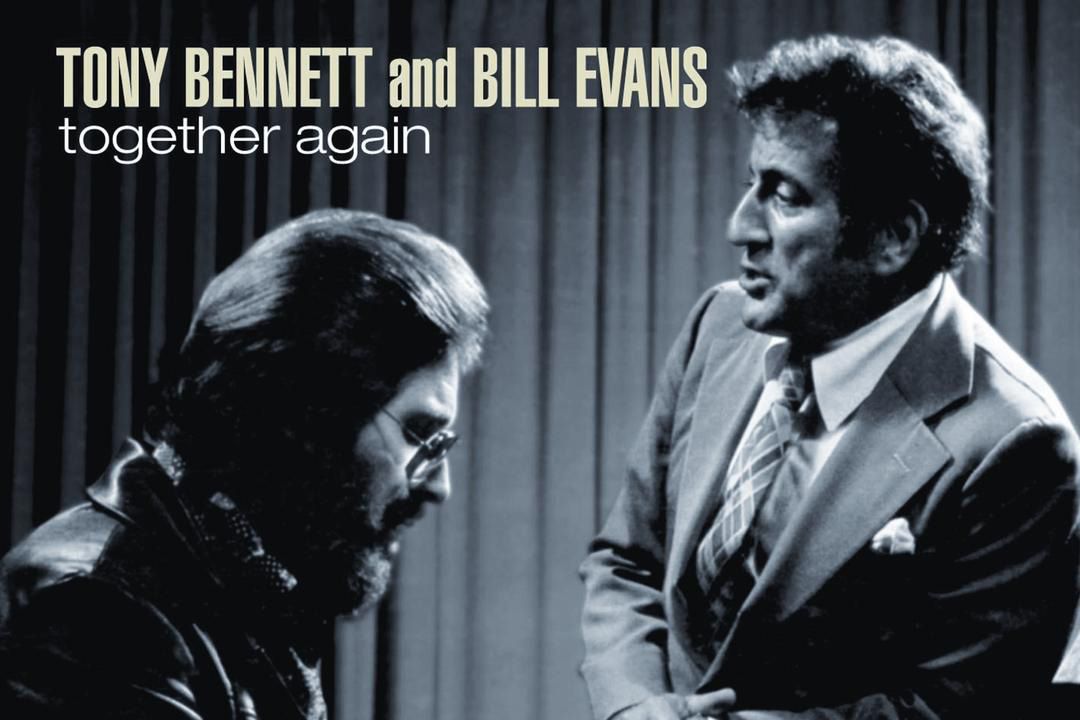

Bill Evans and Tony Bennett recorded two albums together in the 1970s, including the 1977 album "Together Again." (Album Cover)

With his work on legendary jazz albums like Kind of Blue, Portrait In Jazz, Conversations With Myself, and Time Remembered, pianist Bill Evans was one of the most influential and important jazz pianists of the 20th century, with a lyrical touch and unique grasp on harmony. But how was he as an accompanist? This week on the show, I’ll take a look at the few sessions he had with singers over his 25 years in the music industry. On this episode, I feature Evans with singers Tony Bennett, Lucy Reed, Helen Merrill, Mark Murphy and Swedish singer Monica Zetterlund.

Lucy Reed

Bill Evans was born in Plainfield, New Jersey in 1929 to a fairly standard middle class family. Like many kids, he studied classical piano, but soon his world was opened when he learned about the creative potential of jazz.

Evans attended college in Louisiana, studying music, and expanding his skills as an innovative and expressive pianist with a delicate touch and a keen grasp of harmony. After he graduated in 1950, he joined the army for the Korean War, delaying his career. He was discharged in 1954 and moved to New York. Almost instantly, Bill Evans became a talent to watch in the New York jazz scene.

His second recording engagement ever was with an up-and-coming jazz singer in New York by the name of Lucy Reed. Reed had a smoky, seductive voice, like Lee Wiley or Jeri Southern. Evans’s dreamy piano textures make for an excellent background on Reed's 1955 album The Singing Reed.

Helen Merrill

Around 1956, Evans career started taking off. He began working with clarinetist Tony Scott, composer George Russell and most importantly, drummer Paul Motian. He recorded his first album as a leader that year called New Jazz Conceptions. After this, Evans was considered one of the hottest young pianists in jazz, working with Charles Mingus, Gunther Schuller, and performing live with singer Anita O’Day in New York—sadly, Evans and O’Day never recorded together.

Early in 1958, Evans did record with singer Helen Merrill, making an appearance on her album The Nearness Of You. Merrill, like Evans, was part of the New York jazz scene, and her warm, intimate tone made her another perfect match for Evans’s piano playing. Evans did not play on every song on the album, but did accompany Merrill on the Lew Brown, Al Henderson and Buddy DeSylva tune “Just Imagine” and the title track by Hoagy Carmichael and Ned Washington.

"Peace Piece"

Towards the end of 1958, Evans didn’t truly record with any singers. He was the pianist on George Russell’s concept album New York, N.Y., which featured some spoken word from vocalist Jon Hendricks (although no real singing).

It’s also been mistakenly assumed on some discographies that he was the pianist on an album called Chet Baker Introduces Johnny Pace, featuring ballad singer Johnny Pace on vocals, and Chet Baker only on trumpet).

This assumption comes from the scheduling records at the Riverside label. Baker and Pace were finishing up their album together for Riverside on December 30th, 1958. Later that same day in the same studio for the same label and with many of the same musicians, Baker also started recording his solo album called Chet. This album featured Evans on piano, but he probably wasn’t there at the earlier session that day.

What we do know for certain is that two weeks earlier, Evans recorded one of his most consequential albums, the album Everybody Digs Bill Evans. And on that album, he recorded an original song called "Peace Piece."

"Peace Piece" is based around a simple two chord pattern with a falling bassline, and it grew out of a improvisation on the Leonard Bernstein, Betty Comden and Adolph Green tune “Some Other Time,” also recorded for Everybody Digs Bill Evans.

The song would become his sonic signature and would follow Bill Evans for the rest of his career. For instance, you can hear it in the opening of “Flamenco Sketches” on Miles Davis’s Kind Of Blue, where Evans was the pianist. He would even use it years later when he recorded with singers. In 1975, Bill Evans used the "Peace Piece" motto again on his recording of “Some Other Time” with singer Tony Bennett.

Miles Davis, Scott LaFaro and Mark Murphy

In 1959, Bill Evans went from session pianist to jazz superstar when he was brought in to record with Miles Davis for his legendary Kind of Blue session, a landmark album in jazz history and a pioneering work of modal jazz. Evans even helped to co-write the song “Blue In Green,” even though Davis took the credit.

After Kind Of Blue, Evans left the Miles Davis sextet to form his own trio with drummer Paul Motion and bassist Scott LaFaro. Later that year, they recorded the album Portrait In Jazz, another masterpiece from Evans.

However, tragedy struck in 1961 when LaFaro was killed in a car accident, throwing Evans into a spiral of depression and drugs. In order to lift him out of his funk, producer Orrin Keepnews brought him in to record a session with up-and-coming singer Mark Murphy. The album was called Rah!, Murphy’s debut for Riverside Records, featuring the singer on the cover ironically holding up a cheerleading sign while looking bored out of his mind.

Evans only played on two of the tracks, "My Favorite Things" and "Out Of This World." It was pianist Wynton Kelly, who Evans replaced in Miles Davis’ sextet on Kind of Blue, who played on the rest. It’s hard to gauge how much LaFaro’s death was affecting him on this recording session because his performance is buried in the mix. That might be telling though, because why would you hide Bill Evans under horns, bass, and drums unless he wasn’t delivering his usual magic?

Murphy was phenomenon the record, though. On "My Favorite Things," he adds a verse where rattles off a bunch of a jazz stars like Coltrane, Basie, and O’Day as his "favorite things." Unfortunately, that verse is completely missing from the CD reissue of that album. Apparently, the Richard Rodgers estate was not too keen on Murphy changing the lyrics of their beloved tune.

Monica Zetterlund

After this recording session with Mark Murphy, it was many years before Evans recorded with another singer. Those years were filled with recordings with his new trio (featuring new bassist Chuck Israels), a few solo records, and lots of touring. It was also a time where Bill Evans heroin addiction began to spiral further out of control. Yet, artistically, Evans was still going strong.

In 1964, while on tour in Stockholm, he met a young Swedish singer named Monica Zetterlund, who was a fan of Bill’s work, especially his original song “Waltz For Debby.” She even debuted a new version of tune, with a Swedish translation of Gene Lee’s original lyrics. Evans was thrilled and liked her cool vocal delivery, almost like a Swedish Astrud Gilberto.

So while in Stockholm, he recorded an album with Zetterlund, featuring her takes (both in Swedish and English) on some standards, including "Waltz For Debby" (called "Monicas Vals" in Swedish).

Tony Bennett

After Monica Zetterlund, Bill Evans didn’t record with another vocalist for over a decade. In the interim, he worked primarily with bassist Eddie Gomez, keeping the spirit of his trio alive. During this time, Evans began the pendulum swing of getting clean, cycling back and forth between heroin addiction and methadone treatments.

In 1975, on an upswing in Evans’s life, he was put in touch with vocalist Tony Bennett. They had a mutual respect for one another, and many people, including singer Annie Ross and Evans’s manager Helen Keane, had been considering a Bennett/Evans collaboration for some time. Their decision to work together was a natural one—both artists had been committed to their craft, despite the market pressures of the music industry.

Evans had most of the creative control over their album together, The Tony Bennett/Bill Evans Album, working out the structure of the songs that Bennett could sing over. It’s an amazing collaboration where both musicians worked together so seamlessly, but still have their distinct, full artistic voices, not overshadowed by the other.

Bennett would be Bill Evans final collaborator on vocals. His troubled life would come to an end just five years after this recording session, at age 51. But part of their original deal was that the two musicians would record one album for Fantasy Records and another album for Bennett’s own Improv record label. That second album, called Together Again, was released two years later, and has the pair picking up exactly where they left off.