(SOUNDBITE OF BELA FLECK AND THE FLECKTONES’ “BLU-BOP”)

AARON CAIN: Welcome to Profiles from WFIU. I'm Aaron Cain. On Profiles, we talk to notable artists, scholars and public figures to get to know the stories behind their work. On this episode, we feature two conversations about the history and the consequences of the opioid crisis in America.

(SOUNDBITE OF SLOW MEADOW’S “QUINTANA”)

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 130 people in the U.S. die every day after overdosing on opioids, including prescription pain relievers, heroin, and synthetics. Later in this episode, we'll learn more about the toll this crisis is taking close to home in a conversation between two Bloomington residents recorded as part of NPR's StoryCorps project. First, we'll hear from someone who you really could say wrote the book on the opioid crisis in the Midwest.

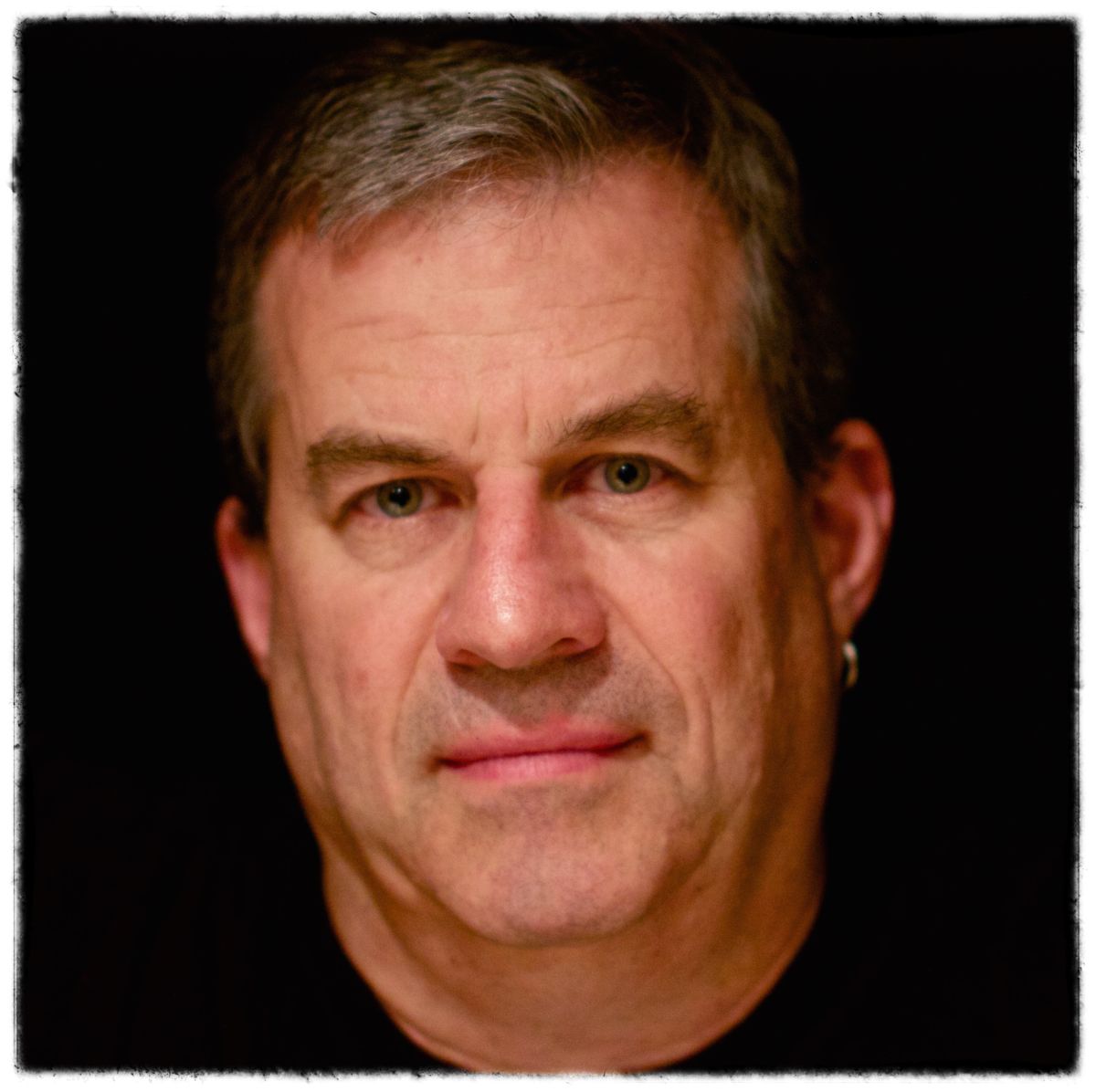

Sam Quinones is a journalist, storyteller and author of three acclaimed books of narrative nonfiction. His most recent book is Dreamland: The True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic, winner of the 2015 National Book Critics Circle Award for general nonfiction. In the book, Quinones provides an in-depth account of the history of the crisis, from the aggressive marketing and prescription of painkillers to how heroin traffickers took advantage of already-addicted communities, to the rise of increasingly potent synthetics like fentanyl. Sam Quinones's career as a journalist has spanned almost 30 years. He lived for 10 of those years as a freelance writer in Mexico. He then returned to the United States to work for the LA Times, covering immigration drug trafficking neighborhood stories and gang activity. In 2014, he left the paper to return to freelancing, working for National Geographic, Pacific Standard magazine, The New York Times, Los Angeles Magazine, and other publications. Recently, Sam Quinones joined me for a conversation in the WFIU studios. And just a brief warning to our listeners: both conversations on today's program are not explicit, exactly, but they contain frank language about drug use and death.

Sam Quinones, thank you so much for joining me on Profiles.

SAM QUINONES: Great to be here, Aaron.

AARON CAIN: So, you're one of those rare people whose titles convey a surprising amount of useful and thought-provoking information. If you look you up on the web, or somewhere, you will see “journalist and storyteller,” and some people might find those to be slightly contradictory. But the more familiar one gets with your work, the more those two words seem to be describing the same thing. And your career as a journalist as spanned, I guess, almost 30 years now. And, even in the beginning, the art of storytelling seems to have been tightly woven into your reporting. So first, I was wondering if we could just talk a bit about journalism, what it means to you, about storytelling, and how those two things interrelate in your work, and what got you into that work back when you first started out.

SAM QUINONES: I wanted a job where I would never be bored, that I would be fulfilled or stimulated constantly. I didn't necessarily need a lot of money, which was good because you're not going to make much as a journalist. But I really didn't want to be confined. I wanted to be able to tell lots of stories, and I believe actually journalists and storyteller are essentially the same thing. Now, storyteller has the connotation that you're making stuff up. But as a journalist you are confined by the facts. But you also need to think of how you're going to tell those facts in a story that appeals to people that brings people in, that leaves them with deeper understanding of the world or that topic than they had before. It's essential. And I think in academia the academics have amazing stories to tell and they tell them so poorly most the time. And I really think they need to spend a whole lot more time thinking about how they're going to tell the stories behind the facts of whatever it is they're studying. So, I view it that way. I view it, like, the storytelling needs as much thought as the gathering of the facts. And it's all part of the beauty of the job, I think.

AARON CAIN: So, I may correct it that back when you attended UC Berkeley, your degrees were not in journalism.

SAM QUINONES: I did not study journalism. I actually think frankly studying journalism is probably a waste of time. I think it's the kind of thing that you learn on the job. I think it's very important while you're in school to study something you love - could be English, could be biology, public finance, psychology, whatever. And then if you're interested in journalism, do the work, you know? Work at the radio station, work at the newspaper, do them all. I mean, work for the magazine, work for the video station, or whatever it is they have. Learn all those trades, all those skills. But, I think, in order to really be the best journalist you can be, I think it's probably more important to study something that you love, because what it all amounts to, what really a college education amounts to, frankly, is teaching you how to learn for the rest of your life. Because if you stop learning, particularly in today's economy, you will be lost, I think, eventually. Time will go on and you will just be lost. And I think in journalism it's really just learning how to learn. That's what the job entails: who to talk to, what questions to ask them, who to find who knows the topic better than you, which would probably be a lot of people. And, so that approach, I think, is very, very important, and important for students to keep in mind.

AARON CAIN: When you were at Berkeley, you lived in a place called Barrington Hall…

SAM QUINONES: (laughs)

AARON CAIN: …The Barrington Hall Co-op. And speaking of things that...

SAM QUINONES: I did.

AARON CAIN: ...that you're passionate about…

SAM QUINONES: …one of the great places to live if you're going to college.

AARON CAIN: …Well…

SAM QUINONES: …it was, at that time.

AARON CAIN: As I understand it, there was a lot of social activism in that community, in that co-op, but also you were producing punk rock performances at the time.

SAM QUINONES: Right. Punk rock concerts. That was 1979, '80, '81 right in there. And punk rock was very big. It's still my favorite kind of rock 'n' roll. And that actually had a lot to do with the rest of my career. I view, kind of, my career since then, particularly in journalism, as very punk rock because much of my career has been as a freelancer. Ten years in Mexico writing freelance. Freelance writing is just about you doing it on your own and creating stories that you then sell. You're basically a mini entrepreneur of stories. And so, I view a lot of what I've done in journalism as very influenced by the idea that you should not wait for permission. You should go out and do it yourself, that it's all up to you. It's a very, very healthy thing for a young person to hear; that no one's going to do it for you. It's all up to you. You have to be the creative one. You have to think of new ways of doing whatever it is you're doing. I think that part of punk rock was extraordinarily helpful, and that's what I was doing. I was just promoting and producing small-scale punk rock concerts in this Barrington Hall, which was a wild co-op that I lived with many of the people I still am friends with from UC Berkeley. Magnificent place to be. It could be very dangerous. There are a lot of drugs and so on. I saw a lot of casualties, but I also saw lots of people kind of, like, become who they really are at Barrington Hall. It was a very, very exciting thing, and for me it was extraordinarily healthy. I did lots of stuff that I would never have done in another situation. It was like a built-in community. And the hall itself was indestructible so we'd have punk rock concerts with 200, 300 people there. And there would be no problem at all. And that was the kind of thing I did for the last - for basically most of my time at Barrington.

AARON CAIN: You honed these boots-on-the-ground, punk-rock journalism, storytelling skills, for one, in Mexico…

SAM QUINONES: Yes.

AARON CAIN: …not too long after a few jobs in various news outlets. When you were there, you spent so much time with so many different kinds of people being exposed to a lot of situations, many of them quite dangerous. First of all, I'm wondering if there are any times when you're really in trouble. But also, as someone who tells these stories, and as someone who collects this exhaustive research and really lives with these stories a long time before they tell them, are you constantly writing, or is there a point where you make that transition from the absorber to the storyteller?

SAM QUINONES: I'm constantly writing. I report and write at the same time. I don't believe in doing lots of reporting then stopping and then going to write. You constantly have to be writing, because you don't know what the questions are until you start to write. Then you go, “oh, my God, I didn't ask that guy whether it was a Thursday or a Saturday that he did this.” And sometimes that's a crucial difference. And you only come to these little questions that are central to telling a strong narrative when you've written it all. So, I found that writing was very important on the job. Every night or every day or every couple of days, writing out what I already had and finding out what other questions I might have, then going back. That was also very, very important. Going back and asking - meeting that person twice, three, four times, because that's how you get to really deep stories. I would say that I was in Mexico, though, at a very, very good time for being a freelance writer. I was very lucky, in fact, to be able to cover Mexico as a freelancer because I did not have editors up in the United States telling me what to do every two or three days. I saw this among my colleagues who were some of the best reporters, by the way, that I've ever worked for. That crew of reporters - I was in Mexico from, like, the late '90s, mid to late '90s for the next several years - some of the very, very best reporters America had produced, I think, during that time, and I was very lucky to be around them. And we formed, I thought, a very, very solid core of reporters during that time. I was lucky, though. Because I was a freelancer, I did not have to obey the dictates of an editor in New York or D.C. or Atlanta or L.A., or someplace. I could just go off and spend three weeks on a story that I was working on and not worry about am I going to get a phone call from some guy who said, “no, no we need you to cover the Mexican Congress.” And I don't want to cover the Mexican Congress right now. I'm much more happy hanging out with the drag queens right now, or this band that I'm touring Mexico with. That allowed me to, I believe, peel back layers of the Mexican onion, so to speak, and see various layers of the country in a way that I don't know that I would have been able to just spending three or four days per story. I was able to spend weeks on stories.

AARON CAIN: I think, going all the way back to one of your first jobs when you were in Stockton, you first probably...

SAM QUINONES: …Yes. Hugely important.

AARON CAIN: …doing some of your first writing on the drug trade…

SAM QUINONES: Yeah.

AARON CAIN: …on the selling of illegal drugs, the violence surrounding it, the economy of it, and also in Mexico, being exposed to it as well, as well as the other element, which is how immigration plays into that.

SAM QUINONES: Yeah.

AARON CAIN: And you have discussed these in numerous pieces, also in three books. The latest of which, Dreamland: The True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic. It's an investigation of opioid abuse in America, including the role of pharmaceutical companies and the Mexican drug cartels in this crisis.

SAM QUINONES: Yes.

AARON CAIN: It won the National Book Critics Circle Award. There have been crises of substance abuse of one kind or another in this country for at least 100 years. And one of the things that your book Dreamland does very well is provide a lot of history and context to that. You take the reader back to the earliest uses of opium in the 19th century, all the way up through today. And after collecting and conveying so many of these facts and so many personal anecdotes in the course of your reporting on the opioid epidemic, in your opinion, what is it that sets this crisis apart from other drug crises?

SAM QUINONES: Well, it's a very good question, and there are several things that make it, I believe, unique, at least in modern America, since the end of World War II. One of them is that this is the first epidemic that we've seen that did not start with drug traffickers or drug peddlers or mafias, or what have you. It does not start there. That's the way the cocaine problem did, marijuana, LSD. All that stuff starts in the underground. And this does not. This starts with pharmaceutical companies and pain specialists uniting to push the idea that doctors should make greater use of narcotic opioid painkillers, which were used in very cautious ways up to that point. And then, doctors being forced or pushed or cajoled or eagerly embracing the idea, and all across the country. And that's being taught in medical schools that this was now the way to treat pain, that patients wouldn't get addicted no matter what the background of that patient was, no matter what the exposure to those pills were, how long it was and what doses, and so on. And this is one of the great differences. And that's why it's so widespread. It's because it was doctors. It was not drug traffickers or drug dealers on the street. And there's, you know, a million plus doctors in this country. And when most of them buy into something, that's going to have an effect. And in this case, a lot of people were treated for pain and a lot of people benefited. I think that the collateral damage has been catastrophic and that a lot of people been very highly damaged, addicted, their families destroyed, their lives destroyed. And that's one difference. The other difference is that this is a silent epidemic. Normally, you get lots and lots of reporting coast to coast. You get lots of lots of attention. It happened with cocaine, as the murder rate in Miami skyrocketed in the early '80s, when the cartels from Colombia were breaking into the Miami and southern Florida markets. It happened with crack very famously across the country. And you got lots of violence. It was very loud, you know, it was very public. The byproducts were very damaging. There were drive-by shootings, you know, carjackings, blighting of neighborhoods, many working-class neighborhoods, many especially black neighborhoods were mightily damaged by that, you know? And you could not avoid it. It was everywhere, and you’d just walk outside you could see it very clearly. This was the opposite. It was a very quiet, and largely because people were silent. People who were affected didn't want people to know. They say, you know, this is an epidemic that's only now being recognized because it affects middle-class white people and that's - there's a lot of truth to that. But I would say for a lot of years it was quiet because it affected mostly middle-class white people, because they didn't want people to know. They wrote obituaries that are pure fabrications about how their son or uncle or wife or husband died. And at the same time as we're seeing overdose deaths increased to the point where they surpassed car fatalities as the leading cause of accidental death in America, we are seeing crime rates decline through - all through those years. The same thing. It's just down to, with a few exceptions, but mostly - city of LA is a perfect example. It's historically low crime in Los Angeles in the last five years, at least, you know? It's been a remarkable time to be in Los Angeles. The gang thing is really retreated. It's not the problem it once was. So, you're getting a drug epidemic in which crime is no longer the barometer. Bodies, in fact, became the barometer. Very sadly so. That's a horrible thing to have to live with, where the way you count how bad it is is through your coroner's office. But that is also one thing that made it very, very different. The widespread nature of it from coast to coast. From Maine to New Mexico to Oregon to Utah to Oklahoma, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Indiana - a big part of it, of course. All of these states were affected by it. I don't know that you could say that about any other previous drug problem, of course, other than, very important to note, alcohol and cigarettes. But they do have something else in common with those drug problems and that is that this starts with legal drugs, legally-prescribed, legally-manufactured, legally-sold drugs starting with primarily pain pills.

(SOUNDBITE OF SLOW MEADOW’S “LAMELLOPHONE AND THE GULF OF MEXICO”)

AARON CAIN: Sam Quinones, journalist and author of three acclaimed books of narrative nonfiction. His latest is Dreamland: The True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic. You're listening to Profiles from WFIU.

This being a crisis that, for a while, was really quiet - there's a lot of reporting about it at present, as people are starting to grapple with how widespread and insidious and how deadly it is. But two things concerning the sale of these pharmaceuticals - one being a key study which, shall we say, was pounced upon by the pharmaceutical industry. I was wondering if you could talk about that, first of all.

SAM QUINONES: Sure. There was a study that I think you're referring to. It was not a study. Dr. Herschel Jick out of Boston - wonderful guy, I interviewed him - ran a database of hospital patient records. And he, in 1979, asked the data computer guy, crunch the data on how many people in that dataset had been prescribed narcotic painkillers while in the hospital and how many of those folks got addicted. And the numbers were 11,000-plus were given those pills while in hospital and four got addicted. So, he writes this up, 101-word letter to the editor of The New England Journal of Medicine, which publishes that letter on the back of the book in 1980, January 1980, under the heading, “Addiction Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics.” And he forgets about that letter. He just said, “OK. I'm on to other things.” He's studying how drugs are used in hospital. That's the main reason for his database. It's a very effective way of saying, you know, how are these drugs, different drugs of all kinds - not just opiates at all, really. It's a lot of different… So, he forgets about that. But that letter to the editor is discovered several years later by pain specialists who begin to cite it because they are pushing the idea that they want doctors to get over the hump, get over the idea that these pills are harmful or risky. They say there are times when these pills are not risky, that they're actually a way of solving our country's pain problem. And that when used in these ways, that they won't be addictive. And they were very intent on that idea. And so, they were looking around for science that showed that. And the problem is there is no science that shows that, regardless of the patient, regardless of the background, regardless of the exposure to the drug., if you are a pain patient, you will not become dependent and then addicted. It will not manifest itself in addiction. So, they look around and they find this one letter to the editor and they begin to cite it and footnote it in different scholarly papers, mention it at continuing medical education seminars and pain conferences, on and on. It ends up being a little bit like a game of telephone, where people start talking about it. And pretty soon its importance is magnified. No one's read it, because that would require going back to the 1980 edition of New England Journal of Medicine which would appear, which is hidden in the back of the library. Nobody got time for that. They're just taking the word of these people, “oh, this is a study!” Or, first it was like, “it's a report!” Well, it's not a report. It's an FYI, Really, it’s all it is. “Hey, by the way, this is what we saw.” Then it's a “study.” And then it's a “landmark report.” And then it's a “landmark study.” Within 15 years, Time Magazine, in 2001, called it “a landmark study that does much to change what we know about a blah, blah…” – nonsense. Total nonsense. Meaning that nobody had read the thing. But it becomes the cornerstone, intellectual cornerstone, scientific cornerstone of this whole movement to prescribe opioids far, far more aggressively, for all manner of conditions. The only caveat being that the person be a pain patient or someone with pain. And that was a big part of what changed a lot of minds. No one had read the thing. Very few people ever read the letter. And now the New England Journal of Medicine puts on top that, unless I looked anyway, there was a banner across that letter. When you look it up online, you will see a banner saying this is not a study, and this is not a report. You should not make research conclusions based on this. You know, I'm not sure if they have any letter to the editor ever in the history of New England Journal of Medicine that has that caveat in bold letters across the top of it. But it did change lots of minds. And it was kind of like the intellectual basis for this broadly-based push to get doctors to prescribe more and more and more pain pills for pain patients. I think well beyond anything that several of the original pain specialists actually wanted or thought wise. But once you push that idea, it gets out into the commercial marketplace and pharmaceutical companies used it in their marketing, used in their advertising. And it just ran with it. They kind of exploded the market.

AARON CAIN: It seems like another catalyst of this explosion was the other thing I wanted to get you to elaborate on which was the defining of pain as the fifth vital sign.

SAM QUINONES: Right. That was important to convince doctors. This was a revolution in pain management that did not take place in the American public. It took place among doctors. So, in order to get doctors to think about pain with more urgency, as if it were really something that they needed to make part of their practice, even though the vast, vast majority of particularly family docs, general practitioner doctors, had no background in pain management, the very, very little understanding of how to treat pain. It was this push to get them to think about paying more. And one way they did that: first it was the American Pain Society, the VA then JCAHO, which accredits hospitals across the country - very large organization. They began to propose the idea that pain should now be considered a fifth vital sign. Meaning, doctors should pay as much attention to that as to pulse, blood pressure, all this stuff. The problem is pain is not a vital sign. A vital sign is something that measures life and stability in life, right? And it's measured objectively. And any day, any moment of the day you can take my pulse and get my blood pressure measured. And that will be an objective measurement. Pain is not objective. It's different, widely different, depending on the human being, depending on the moment of the day of that human being, a variety of things. Plus, the crucial thing, too, is doctors were then pressured to batter pain down to zero. Well, nobody batters a vital sign down to zero. Battling the pulse down to zero means you're dead. So, this is the only vital sign, supposedly, that was pushed to be knocked down to zero. It had the effect of really, really helping convince a lot of doctors that this was a new world, that what they'd known up to now was not true, that this wariness about using narcotics was really misplaced, and that they needed to really get with the new program and pain as fifth vital sign had a outsized effect on doctors thinking across the country, I think, just from anecdotally talking with docs who were practicing at that time.

(SOUNDBITE OF SLOW MEADOW’S “LAMELLOPHONE AND THE GULF OF MEXICO”)

AARON CAIN: You're listening to Profiles from WFIU. you. On this program, we're featuring two conversations about the opioid crisis in America. Our first is with Sam Quinones, journalist and author of Dreamland: The True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic.

As you point out in your book, this crisis is not just about prescription drugs, though. It really is kind of, like, two crises. There's been a commensurate rise in heroin use…

SAM QUINONES: Yes.

AARON CAIN: …in the U.S. At the same time - black tar heroin, to be more precise…

SAM QUINONES: Yes.

AARON CAIN: …that, extraordinarily, seems to be coming from one tiny city in Mexico.

SAM QUINONES: Well, I wrote about one town that was a leader in that. They were not the only ones.

AARON CAIN: Okay.

SAM QUINONES: The town of Jalisco in the state of Nayarit was not the only place. Their importance to this story is not that they're the only purveyors of black tar heroin in Mexico. Their importance to this story is rather that they traveled with this system of selling black tar heroin as if it were pizza delivery, and delivering it to addicts. It was very expansionary, like, a capitalist franchise. It just moved out to new markets constantly and happened to land in Columbus, Ohio and then other places, as well - like Indianapolis, and then finally Bloomington - at just about the time when the mass promotion of pain pills was occurring. They dovetail. So, these guys were the first heroin traffickers to recognize and then systematically exploit - with their pizza delivery kind of system of heroin - this emerging new market of heroin. So, they're not the only ones coming out of Mexico but they were the most aggressive and they were the most creative, in an entrepreneurial sense. Because of that, they were placed in the area where this thing really began to explode in, you know, '97 '98 is when they arrive in Columbus, Ohio. And then from then on it's, like, other towns that are nearby. So, Indianapolis was one of them.

AARON CAIN: Can you talk a little bit more about their rather extraordinary business model because it's incredibly efficient and cheap...

SAM QUINONES: Sure. It's one that was used in Indianapolis and may still be. I'm not up on what that new thing is these days. But the idea was that we should provide addicts with what they most prize. And that was convenience. So, you don't have to go looking all over town. You don't have to go to some seedy motel or housing project or cantina to get this stuff. We will deliver it to you. And the other thing that's most important to addicts is reliability. We will deliver it to you on time and in the same dose that you're used to. And you won't get robbed. All of that is very important. So, the system was really very much like pizza delivery. There's a operator with a telephone number, sets up in the town. Has three or four drivers driving around town with little balloons of black tar heroin in their mouths. And then maybe a big canister somewhere else hidden in the car. A big bottle of water, in case the cops stop them; takes it, swigs it down, swallows the balloons. The addict calls the number. The operator dispatches one of the drivers tooling around town to go meet the addict in, say, a Speedway gas station or a Burger King parking lot, or someplace like that. And they make the deal. That's how it works. And it was very, very low quantity, you know, retail sales - tenth of a gram, quarter gram, maybe a gram – Much higher than that, and they started to suspect that maybe it was a police officer. You know, they didn’t want to deal with that. So that system was designed through trial and error to appeal to addicts most important needs, which is consistency, safety, don't have to travel all over the place, convenience, et cetera. And that system they took from the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles in the early '80s. And, again, they expanded. They were all from the same town. These guys were all from the same town. And they began to expand. And they expanded because they couldn't kill each other, you know? In the underworld, the way of dealing with competition is to pull out a gun and shoot the competition. Well, these guys are all from the same town. They couldn't do that because they're all from the same town. They know each other. They're - sometimes they're even related. And they know we're each other's mothers live, you know? So, expansion was the name of the game. So, they're from San Fernando Valley. It was to San Diego. It was up to Reno. Portland was a big hub for a long time. Denver, Salt Lake, Boise. But then in the late '90s, they jumped the Mississippi River. One guy in particular jumps the Mississippi River and lands in - first in Indianapolis and then leaves Indy to Dayton and leaves Dayton, finally lands in Columbus in the summer of 1998, just as Columbus is really kind of, like, the northern outpost or ground zero for this thing that's beginning in Appalachia, really. And so, they're dope, sold like this, begins to spread beyond just the town. And it gets out into the suburbs, and then finally the rural areas. And people who are addicted to the pills realize that it's actually far cheaper to buy this very potent heroin. It comes to Indianapolis through a couple of guys I interviewed in the book. And they're kind of like regional sales managers in this kind of thing. And then eventually a few students from Bloomington begin to go up and bring it back here, and so you begin to see this in the early 2000s, some students getting addicted. But that's the way it works. The heroin is sold in the hub cities - Nashville, Charlotte, Minneapolis, Indianapolis, etc, all these kinds of mid-sized towns that don't have any drug competition, really. And then through people coming to the cities and buying and going home. That's way it spread. But these guys from this one town in Mexico figured this out. They were early adopters of this, and they realized that if we follow the pills - once they get to Columbus, they realize, “if we – gee…” It’s dawning on them. It's an insight that, “if we follow the pills, we'll have a huge market for heroin, the kind of which we never would have imagined five years ago.”

AARON CAIN: And that's indeed what seems to have happened.

SAM QUINONES: Oh, that's exactly what happened. Now then, of course, they've been eclipsed because now everybody's in this market. Huge numbers of people. And here, here in the United States, as well as down in Mexico, they're no longer the pioneers, so to speak, nor the important players in the markets where they landed that they once were. But that's because the market for pills has exploded into a market for heroin, and then a market, now, for fentanyl, because the traffickers in Mexico figured out: why grow a plant? Why rely on the weather? Why have peasant farmers harvesting the stuff? Just make it in a laboratory in a factory somewhere in a warehouse in Mexico - and then fentanyl kind of crowded out the heroin, so that's where we are now.

AARON CAIN: I'd like to ask you, if I could, about addiction itself. What would you like people to understand?

SAM QUINONES: I think, particularly, advances in brain science and knowledge of the brain - while we have vast territory still to go, it's one of the - you know, the universe and the brain are the two most impenetrable areas of study, seems to me. We have very far to go in the brain. It seems to me now, though, that the knowledge is pretty clear that dependence begins with a change in the way the brain behaves under these drugs. And then addiction is, you know, the street manifestation of dependence where you're looking constantly for the drug and creating enormous harm in your life - in your family life, jobs, and so on and your own physical well-being once you're out on the streets. It does feel to me like the knowledge is such that it's clear that this is a problem that really does change the brain in fundamental, important ways, and creates impulses and cravings that - very, very hard to overcome, and create the kind of - I would say almost that it frequently manifests itself in kind of, like, the lack of free will that you would say, ”gee, that looks a lot like…slavery, or some form of it,” you know, where you are just obedient to the dope. The dope is telling you, “you've got to have me” - and particularly true of the opiates and the heroin, and whatnot. It's like a jealous lover. “You have to be with me. And if you try to get away from me, I will throw a massive tantrum.” And that's called withdrawals. And you begin to have diarrhea and sweating and can't sleep and it goes on for weeks and it's just this horrible nightmare of an experience. You think you're going to die. All of that is part of my changing in how I view this, largely due to talking with neuroscientists, though, about how the brain is changed once you are addicted. That's not to say I don't think that there's no personal responsibility in all this. There is a point where you, as an addict, need to work at improving yourself - improve on, you know, family relations and working, and so on. This is part of it. I don't think we can just say that we are robots and this drug is pushing a button constantly. Particularly in recovery there - you know, it comes time now to work on yourself, and needs to be done very seriously, and I've seen people do that and I've seen people change their lives in very impressive and admirable ways, I would say. But I'm pretty clear now in talking with neuroscientists that what happens in the brain is a profound thing - this changing of how the brain works to make it so that you are not behaving the way your body used to behave when you were - it's like almost another person has inhabited your body, you know? And that's something that a lot of people notice about loved ones who get addicted - it's all of a sudden that same person - it's - the physical person is the same, but the behavior is radically different, and somehow incapable of doing anything else, you know?

AARON CAIN: Finally, I want to seize upon something you just mentioned about the importance of self-improvement and how it is still relevant when you're combating something as mighty as opioid addiction. In 2018, you testified at a congressional hearing on the opioid epidemic occurring in so many communities around the country…

SAM QUINONES: Yes.

AARON CAIN: …and one of the things that you said is that there is no solution to this problem. There are many solutions and that one of them involves communities.

SAM QUINONES: Yes, I believe that very strongly now after having written about this and then traveled around the country talking about it for the last four years. I do believe that it's very, very important to understand that addiction by itself is just one of the almost isolating acts we do. We're already kind of isolated in America. We have lots of ways in which we isolate ourselves - in our houses, with our screens, with - you know, professionally, politically, et cetera. But addiction takes that to an extreme. And so, addicts frequently are just all by themselves. It's all about self-gratification. It's all about what I need. And so it seems to me that something that creates isolation, that begins really with isolation, and begins really with addiction to the most isolating drug we know, which is the opiate class of drugs - that really the way to approach it - to address it is through community - rebuilding those shorn and shredded ties of community that once bound us more deeply than we have today. And that's what I think you're finding all across the country - and I think that that is the beauty of this epidemic, in fact. It's hard to say that, I know, because of the damage it's done. But so many people around the country now seem to realize that, and are responding in this way, to kind of come together. Lot of ways to go and a lot of people are not, but I do believe that I'm seeing this everywhere I go, where people are coming together - lots of different folks. Not just cops and judges and sheriffs, but clergy and PTAs and Kiwanis and Chamber and all these different groups kind of coming together to leverage all the talents and figure out on their own - in a very punk rock way, by the way, you know? In a very do-it-yourself - they're not waiting for permission from anybody. No studies showing them, “this was what - the 10 things you have to do.” No, they're just doing it. I love that. I just think that's so healthy. And that's the healthy response to this epidemic that has been so deadly and damaging to our country - people coming together, learning how to work together again - just being together repairing that community idea that we need - deeply need - as human beings that has been shorn in so many ways in so many parts of the country. I just think it's so important to do that. And so, to me, that is really where the positives lie in this. And the more we can do that, the more people who get involved in that - with realistic expectations. Nobody's changing the world here. It's small stuff - small steps towards repairing massive damage to our body organism - our body politic, which has been shorn of community connections in a million different ways for a long time now.

AARON CAIN: Sam Quinones, thank you so much for your important work and thank you so much for speaking with me today.

SAM QUINONES: It's really great of you to have me on, Aaron. I appreciate it so much.

(SOUNDBITE OF SLOW MEADOW'S "SHIPS ALONG THE HARBOR")

AARON CAIN: Sam Quinones - journalist, storyteller and author of Dreamland: The True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic, winner of the 2015 National Book Critics Circle Award. You're listening to Profiles from WFIU. I'm Aaron Cain. On this episode, we're featuring two conversations about the opioid crisis in America. Our second conversation is between Bloomington residents Karen McKibben and Dru Presti-Stringfellow. They shared their personal story with NPR's StoryCorps when they visited Bloomington in 2017. And Karen and Dru's story reveals just how deeply this epidemic has affected the people in so many communities. And it also reveals the sometimes-unexpected ways in which communities come together in response.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: So, Karen. You were the first wife.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: (laughs)

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: And I am the second wife. You had Joseph in 1984 and Philip in 1986, and I came into their lives when Joe was 4 and Philip was 2. And a year later Keaton was born in 1989. So, we met in 1988.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: Yes. The early years. Married to my first husband - a.k.a. your second husband. They were tumultuous, but in many respects, I loved being a mom to Joe and Phil. I grew. The divorce was hard. I grew. Getting to know you was hard - probably the hardest thing because I liked you and you were married to my ex-husband that no longer was a part of my life. And I never really got to know Keaton until you permitted it. You gated me off.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: We had a rough start.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: We had a really rocky start. I think we would have run each other down had we had the opportunity.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: We didn't like one another. We didn't give each other a chance, really.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: No.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: But when my relationship with Rick ended - and I do feel like you always tried hard to have something with me. We came together. And I don't know if you remember that first luncheon we had where we were trying to be friends and you were talking about, “Rick this” and “Rick that,” and I said to you, “if this needs to be about Rick, it can't be. It can't be what our relationship's based on.” And you stepped into that and we built our relationship.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: I remember that lunch. I remember you giving me the boundaries. And I thought, there's got to be more to this than just talking about each of our ex-husbands, which happened to be the same person. And so, we began to focus on the kids.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: The kids. It was all about the kids. I was determined to stay in their lives, so it was our focus. The children were our focus. And over the years your second-born, Phillip, developed some issues with drug addiction.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: Wow. Yeah, Philip was ADD, as I am. They put him on a drug for that, which unfortunately, as I read in his journal years later, began his love affair with the effects of a mind-altering drug. And it engulfed his elementary classes. It engulfed his middle school. It engulfed high school. It engulfed everything. And it tested my marriage. It tested me. It was either a do or die for me, and I decided to stick around and see if I could keep my child alive.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: I remember early on you had premonitions that we would not have Philip for very long. You have said that to me over the years. It's a Spidey sense - a mommy Spidey sense, right? That you had going on.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: I knew from middle school on. If it didn't involve a risk, he wasn't interested in it. He was gifted in everything that he did. He was a successful songwriter, a lyricist. He had it all. And he knew he had it all, and he used it. And I read in his journals, too, where his abilities to manipulate people allowed him to always use the shortcut. He never had to work for things like other people did. He always accomplished whatever he wanted to with his shortcuts. I saw, and I felt in my gut - I can either hold on and, like many parents that knew that their kids were using drugs, I could pretend like it wasn't happening. Or I could get in there and I could just try to separate the drug addiction from the child and keep my child close, because I couldn't change anything about the drugs. I think of both my boys - Joseph being the oldest, sitting on the sidelines all those years, him too being helpless to help his best friend and his brother. I think that was the challenge that all of us had was they knew my gut stood the test. They knew when I said I don't see having him long if he keeps up this lifestyle - and we lost him. And he was a pain in the ass, but he was my pain in the ass. And he was also one of the sweetest, most loving, kindest individuals I'd ever met. But you - you came out of the woodwork when that happened. And rather than see you once a month or once every six weeks, you showed up on the day he died, on the night he died, at the hospital. And you showed up at my house every single day - every single day for the entire month of September. You came so often that the house seemed empty if you weren't there. It was missing even more than Phillip. You kind of filled the void for me about having another person there that I loved. And through that experience, I grew to care for you in more ways than I do my family of origin because they weren't there and you had been with me in the dog fight from the beginning.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: So, Phillip died of a heroin overdose. We consider him part of the opioid epidemic in our nation. But being an addict is not Philip.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: No.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: He's oh so much more. So, he was in and out of rehab more times than we can count. He never seemingly chose sobriety. He had overdosed two times before the fatal overdose and survived them. The first one in October of '15, the second one on Mother's Day of '16, and the fatal one on Labor Day of '16. But before he died, he got to go on the trip.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: The trip.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: We didn't think he was going to be able to go. He was supposed to be in rehab.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: Well, he was supposed to be a lot of things. He had named this trip. The three brothers had gotten together a year before and they decided that they were going to take a trip annually for the rest of their lives.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: A bro trip.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: A bro trip. This trip was called the “Stringfellowship.” As the month approached -August of 2016 - as that month grew closer and closer, he was in and out of rehab. He was in and out of relapses and he had decided, because he was in a job, that he couldn't go. He didn't have the money, he didn't have the time, he didn't think he deserved to go. And then five days before the trip, he came to me and he said, “I got to go on this trip, mom. I have to.” And I don't know why I didn't question it, because any rationally-thinking mother would have said, “well, you don't have the money and you don't have the time and you just got out of rehab and you really need to focus on your sobriety and you need - you need - you need - you need.” And then I trashed all those thoughts and I looked at him and I said, “you're right. You've got to go. You're absolutely right.” He said, “I paid for everything that I needed to pay for, mom, except I don't have a flight home from Colorado.” I said, “I'll get on that and you'll have a flight home by the end of the day.” So, they went on a trip. They all flew to Seattle. They rented an SUV and camped out and toured national parks.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: Starting in Glacier, making their way down to Phoenix. A two-week trip.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: And I think for Philip that was his swan song. I think he knew it was his swan song. And he came home and I picked him up. He was clean and happy and rugged-looking. And he went to work for another week and he came home again that Friday and he was great. He was in a funny mood. He was needing to be with my husband and I. And we played Scrabble and, of course, he let me win 'cause I cheat. I have to cheat to win. And he was in a great mood Saturday and we went out for lunch and he was in a wonderful mood. And then Sunday morning I went to church and I came home and he was waiting on me - he'd already texted me two or three times asking me when I was going to come home. And he met me at the door. And I looked at his eyes. And I knew. I knew he was going to use. I knew it, and he left that morning, came back that afternoon, had already been using. But I couldn't kick him out. I just couldn't make him leave. It was so late. And so, we talked about it knowing he'd have to leave the next day because the rule in the house is if you use or bring drugs into the house you got to go. And he knew that. But he looked up at me with those eyes and he said, “don't worry, Mom, it'll be OK.” I said, “OK.” He said, “I'm going to go take a shower.” And I went to bed. And then about a half hour later, I couldn't hear any noise. I couldn't hear any doors. I couldn't hear anything. And so, it concerned me. And I checked the bathroom. The door was locked. By the time that we got to him after kick in the door in, he was gone. So, he died within a half an hour of saying, “don't worry, Mom, it's going to be OK.” And from that point, you came into the picture as did three other outside people out of the family. And we all stayed together in the consultation room at the hospital where we just took our turn saying goodbye to Phil for the last time. I would say that was the hardest night of my life, but it's not. It's not even close as to how hard every morning is knowing, “damn, I'm going to spend another day without him.” And that's how I count the days now. “OK, one more day without Phil. I can do it. I can do it. Just one more day without Phil.” But I think the blessing in this whole mess is that our family is so tight now. It just forced us to look at each other in a different light. I value you. I value everything you've given us since Phil passed. I value how you try to make sure that your son and Joseph, my other son, remain close. I value how you keep checking in on me, how you conjure up these little projects you want me to do just so I'll get over there near your house and you can watch me. And I thank you for that.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: It's the forever. Grief isn't forever, the loss is the yesterday that we will always have so fresh in our minds, and the forever is the slogging through the grief of this tragedy. And it is a tragedy. Do you want to talk about the celebration?

KAREN MCKIBBEN: The celebration. I could not have a funeral for him. It didn't seem fitting. Phil liked to sing, and he'd liked to engage. And he'd liked to meet people. And he liked people to be happy around him. So, a funeral wasn't going to work. And we had him cremated because that's what I - he actually told a friend of his that when he died he wanted to be cremated. So, I think he knew his time on this earth was short, too. And so, he was cremated. And at the celebration, which was a month later, October 1. I remember we went out very early and we set up. There's a lot of tables set up. And so, we took down half of them because we didn't think that many people would show. And it was at my church. And the closer it got people started streaming in where we ran out of tables. And they were lined up in the doors outside of the sanctuary. And it was a wonderful gathering of people who really - most of them did not know Phil. They were there for his family. It was a testament as to Phil's life did matter. And it gave me great joy to tell people about my son that only knew him maybe as, oh, just another heroin addict. No, he wasn't. Here's the side of Phil I want you to see that you will never see, never could have seen because he never let you see him. Phil hid his addiction very, very well. And so many people were stunned that such a remarkable man could die so suddenly that way. And they didn't know him at all.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: We had his music playing. We had photos. We spent hours pulling together photos...

KAREN MCKIBBEN: Hundreds of photos.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: Hundreds of photos and had a snippet of video pulled together playing, too. And a lot of those people had not heard Philip's music. And they got to. And you were very forthright in talking about his addiction and the fact that it did not define who he was as a person.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: When Phil went into that bathroom, I don't think he intended on coming out. I think he had disappointed himself as much as he could have. And I don't think he wanted to put us through anything else, nor himself, nor his son. We haven't even mentioned little Emory Joe.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: We haven't mentioned Emory. Let's talk about Emory because Emory was born in 2014 and Phillip was actually using that night.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: He was high when Emory was born.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: But Emory is a little piece of Phillip. And you cannot look at that child not see Phillip.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: He's a joy. He's the gift that Phillip has given everyone. Every one of us have benefited from knowing Emory. And Emory Joe talks about his daddy all the time. And I show videos of his daddy all the time.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: When I spoke at the celebration, I pulled out two things. I pulled out a Facebook post on Phil's wall that said, “if love could have saved you, you would have lived forever.” And I pulled out a piece of Phillip's lyrics that said, “the power of love. That's the real magic.” And it is. It's been our story. Love won. Love won one and gave us each other and our families. And I'm grateful.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: I'm just grateful to be able to talk about Phil.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: We never get tired of hearing about Phil or talking about Phil.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: And his brothers. Even though they were kind of in the shadows for the last two years when Philip was such an active user. I thought he was going to take us out, too, with him. Because I would have done anything to keep him alive.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: Loving an addict. Anything you want to say to others that love an addict?

KAREN MCKIBBEN: Hmmm. I guess I'd have to say, if you do love an addict, the best thing you can do is what I did. Join groups of people that are also loving addicts and be sure to take care of yourself because you're not going to be able to control or stop that addict from using if they want to use. The only thing you can do is try to be there for those people that are left. And that's what I did. And I opened myself up. And I have had many people call me and talk to me about their addict. That's all I can do. That's my gift back to them that Philip gave me.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: Anything you want to share about living in grief?

KAREN MCKIBBEN: It sucks.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: Yes, it does.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: It really sucks.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: The unimaginable of losing a child, an unfinished life.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: No, there's nothing I can add to loving an addict. My other son loved an addict. My husband loved an addict. You loved an addict. We all loved an addict. Emory loved an addict.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: Yeah.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: But he was so much more than that. That was just his disease. That wasn't who he was. And I make sure that the people I talk with know who he was. I'm not ashamed of him at all. I hate the disease, but I loved my son.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: Well, I'm grateful to be part of this family.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: You are family.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: And, in the aftermath of this, find a lot of comfort in our friendship and in each other's homes. And in the ways in which we will never let Phillip be forgotten. And Emory will always hear about his daddy.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: I'd say we've come a long way since we used to aim for each other in the highway.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: Can't even imagine it.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: We've done good.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: Thank you for those boys.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: You're welcome.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: They've meant a lot to me and continue to, and...

KAREN MCKIBBEN: We have good kids.

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: We have amazing children from our ex-husband.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: (Laughter).

DRU PRESTI-STRINGFELLOW: That's our gift from him. It's the only one. It is our gift from him, and we're grateful. I love you. And thank you for being my family.

KAREN MCKIBBEN: I love you too.

(SOUNDBITE OF SLOW MEADOW’S “QUINTANA”)

>>AARON CAIN: Dru Presti-Stringfellow and Karen McKibben. Karen and Dru's conversation was recorded by NPR's StoryCorps during their visit to Bloomington in the summer of 2017. You've been listening to Profiles from WFIU. Thanks also to our first guest. Sam Quinones. His award-winning book on the national opioid epidemic and its history is called Dreamland. If you need help resources or information about the national opioid crisis, visit hhs.gov/opiods, or call their national helpline at 1-800-662-4357. I'm Aaron Cain. Thanks for listening.

Mark Chilla: Copies of this and other programs can be obtained by calling 812-855-1357. Information about Profiles, including archives of past shows, can be found at our website: wfiu.org. Profiles is a production of WFIU and comes from the studios of Indiana University. The producer is Aaron Cain. The studio engineer and radio audio director is Michael Paskash. The executive producer is John Bailey. Please join us next week for another edition of Profiles.