Welcome to Night Lights… I’m David Brent Johnson. In the early 1950s drummer Shelly Manne settled in California and began a remarkable run of recordings that included experimental jazz, popular interpretations of Broadway scores, music for the TV crime show Peter Gunn, one of avant-garde icon Ornette Coleman’s first albums, and charged live performances at San Francisco’s Black Hawk club. In the next hour we’ll hear samples of all of them. It’s “West Coast Manne: Shelly Manne In The 1950s…” coming up on this edition of Night Lights.

Shelly Manne, “Slan” (4:51)

Drummer Shelly Manne performing “Slan,” written by saxophonist Charlie Mariano, with pianist Russ Freeman, bassist Leroy Vinnegar, and trumpeter Stu Williamson as well, (from the album SWINGING SOUNDS.

Shelly Manne was one of the most versatile drummers in jazz history. He started with the big bands at the dawn of the 1940s, became a fixture on New York’s 52nd Street bebop scene, and after a long stint with Stan Kenton’s massive orchestra landed in California, where his prolific run of recordings in the 1950s included experimental and West Coast jazz, music adapted from Broadway musicals and TV shows, hardbop and all-star trio dates, and appearances on iconic albums by saxophonists Sonny Rollins and free-jazz pioneer Ornette Coleman. As his jazz-goes-Broadway collaborator pianist Andre Previn said, “He can sit in any rhythm section, from a trio to the biggest band and make it swing; he is an experimenter and innovator of the highest order; he can, when the occasion calls for it, subdue himself to fit any style of soloist; and he is a solo drummer of exceptional skill and taste. Probably his greatest attribute is his insatiable musical curiosity.”

Shelly Manne was born on June 11, 1920 in New York City. He didn’t actually start playing the drums till he was 18, but he quickly established himself in the early 1940s, at home in both large swing ensembles and small groups. He married Florence Butterfield, a Rockette dancer also known as “Flip,” in 1943, and served in the Coast Guard for three years during World War II. After getting out he recorded with rising bebop star Dizzy Gillespie, then signed on with Stan Kenton’s progressive-jazz big band. In 1951 Manne left Kenton’s orchestra and settled in California. He was one of several Kenton sidemen to do so, helping to form the nucleus of musicians who would give birth to the movement known as West Coast jazz. Manne was a regular drummer at Hermosa Beach’s Lighthouse Café sessions that included many of the artists such as Shorty Rogers and Jimmy Giuffre who would appear on Manne’s recordings for the Contemporary label in the early-to-mid 1950s. We’ll hear music from Manne’s first album now—a Jimmy Giuffre composition called “Fugue” that Ted Gioia has singled out as “one of the most strikingly avant-garde compositions of the early 1950s… its atonality and its obvious destruction of the typical roles played by the rhythm instruments made this work especially iconoclastic.” First, we’ll hear Manne’s own composition “Grasshopper,” on Night Lights:

Shelly Manne, “Grasshopper” (2:46)

Shelly Manne, “Fugue” (2:45) (total time: 5:31)

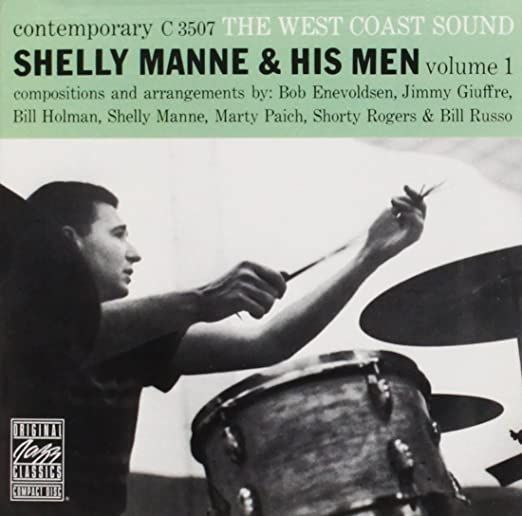

Shelly Manne performing Jimmy Giuffre’s “Fugue” and Manne’s own composition “Grasshopper” before that, both from SHELLY MANNE AND HIS MEN Volume 1: THE WEST COAST SOUND.

Manne could play well in just about any jazz context. He was less focused on virtuoso technique and powerhouse displays than he was on being melodically sensitive to the music at hand, and he was repeatedly praised for this sensitivity by his fellow musicians. But he came to be strongly associated, sometimes to his frustration, with the sound known as “West Coast jazz.” In his book about the genre Ted Gioia writes, “The role of a West Coast drummer was beset by many contradictions. The experimentation of the Los Angeles musicians focused on the innovative use of horn lines, harmony and composition and only occasionally approached new ways of treating the rhythm section. Little wonder that the stereotypical West Coast approach to percussion, exemplified by Shelly Manne and Chico Hamilton, attempted to make the drums into a horn-like instrument, one in which rhythmic drive was often subservient to melodic continuity.”

Manne’s early albums for Contemporary provide some of the most outstanding examples of 1950s West Coast jazz in its more abstract and experimental moments. At the same time, he played with a quiet fire that belied the charge of cerebralism often leveled against such music. We’ll hear two recordings now from 1954 sessions released as THE THREE AND THE TWO, starting with a Manne tune named after his wife that relies solely on trumpeter Shorty Rogers, clarinetist Jimmy Giuffre, and Manne himself--as one writer notes, “without the benefit of any harmony and bass underpinning. So subtle, swinging and orchestral is Shelly’s percussive touch that no other support seems necessary.” Shelly Manne and “Flip,” on Night Lights:

Shelly Manne, “Flip” (2:56)

Shelly Manne, “Billie’s Bounce” (4:07) (total time: 7:03)

Drummer Shelly Manne and pianist Russ Freeman performing “Billie’s Bounce” from the album THE THREE AND THE TWO. From that same album we heard Manne, trumpeter Shorty Rogers, and clarinetist Jimmy Giuffre doing Manne’s composition “Flip.”

Manne’s adventurous 1950s West Coast jazz recordings also included several extended compositional suites by saxophonists Charlie Mariano and Bill Holman and clarinetist Bill Smith. “I find it broadens my musical knowledge to play such works,” he said, “and I feel that if the composer is also a jazz musician, he keeps the traces of jazz in terms of conception and sound.” We’ll hear excerpts from Holman’s “Quartet,” which Manne recorded in 1956, that feature Mariano on alto sax. Holman wrote the suite in four parts to emulate the structure of a sonata—“not because it is a classical form,” he wrote, “but because it has proved itself, through centuries of use, capable as supporting (as framework) a composition of this length.” Still, Manne’s recording of this and other extended works added to the notion that West Coast jazz in the 1950s harbored cultural ambitions on par with Duke Ellington’s prior forays into more expansive compositional territory. Here’s Shelly Manne performing Bill Holman’s “Quartet,” on Night Lights:

Shelly Manne, “Quartet Pt. 1 and 2”

Shelly Manne performing the first and second movements from Bill Holman’s“Quartet” suite from the 1957 album MORE SWINGING SOUNDS, with Charlie Mariano on alto sax, Stu Williamson on trumpet and valve trombone, Russ Freeman on piano, and Leroy Vinnegar on bass. I’ll have more of Shelly Manne’s 1950s music in just a few moments. You can hear many previous Night Lights programs on our website at wfiu.org/nightlights. Production support for Night Lights comes from Columbus Visitor's Center, celebrating EVERYWHERE ART AND UNEXPECTED ARCHITECTURE in Columbus, Indiana. Modern architecture and design to explore forty-five minutes south of Indianapolis. More at Columbus dot I-N dot U-S. I’m David Brent Johnson, and you’re listening to “West Coast Manne: Shelly Manne In The 1950s” on Night Lights.

Shelly Manne, “Parthenia” (1:00)

I’m featuring recordings made by drummer Shelly Manne in the 1950s on this edition of Night Lights. While much of Manne’s early-to-mid 1950s work is often categorized as experimental West Coast jazz, he was also at the forefront of what became a very commercial trend later in the decade—adapting Broadway scores for jazz settings. It came about at a 1956 trio date for Manne, pianist Andre Previn, and bassist Leroy Vinnegar; with no planned material at hand, producer Les Koenig suggested that they try a couple of tunes from the hit musical MY FAIR LADY. Pleased with the results, Manne decided on the spot to do a whole album of the Lerner and Loewe songs, and its subsequent success launched the “jazz-goes-Broadway” genre, with shows such as WEST SIDE STORY, PAL JOEY, and BELLS ARE RINGING being mined in a similar manner. We’ll hear music from Manne’s MY FAIR LADY lp, as well as music from one of several dates he did in the late 1950s as part of a trio called “The Poll Winners” that focused on jazz standards and popular song repertoire. Here’s Shelly Manne with “Get Me To The Church On Time,” on Night Lights:

Shelly Manne, “Get Me To The Church On Time” (4:11)

Poll Winners, “Jordu” (3:28) (total time: 7:39)

The Poll Winners in 1957 doing Duke Jordan’s “Jordu,” with Barney Kessel on guitar, Ray Brown on bass, and Shelly Manne on drums, from the first of several Poll Winner albums that the trio would record for the Contemporary label in the late 1950s. Before that we heard Manne with pianist Andre Previn and bassist Leroy Vinnegar doing “Get Me To The Church On Time,” from their bestselling adaptation of Lerner and Loewe’s MY FAIR LADY musical, recorded in 1956.

As the 1950s progressed Manne also became more involved in film and television work, including a prominent role in helping Frank Sinatra with his part as a drug-addicted drummer in the 1956 movie THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM. Perhaps most notably, Manne recorded two albums of the music that Henry Mancini wrote for the jazz-themed TV detective show PETER GUNN. Manne and other West Coast jazz artists could sometimes be seen on the show as well, playing in club scenes. While the theme song has become iconic, we’re going to hear another, lesser-heard Mancini composition from the first album that Manne recorded.. here’s “Sorta Blue,” on Night Lights:

Shelly Manne, “Sorta Blue” (4:10)

Shelly Manne performing Henry Mancini’s “Sorta Blue” from the 1959 album SHELLY MANNE AND HIS MEN PLAY PETER GUNN, with Conte Candoli on trumpet, Russ Freeman on piano, Victor Feldman on marimba, and Monty Budwig on bass. Manne would go on to collaborate with Mancini on recordings for the movies BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S and THE PINK PANTHER.

Manne also shows up on some classic late 1950s albums as a sideman—he was the drummer on saxophonist Sonny Rollin’s landmark trio date WAY OUT WEST. “Shelly freed me as a frontline player,” Rollins later said. “He was able to be there and not be there… He knew just what to play behind me while providing an underlying swing and groove.” That ability served Manne well when he was asked to play on an early 1959 album by saxophonist and free-jazz pioneer Ornette Coleman, in the piano-less quartet format that Coleman preferred. Coleman’s revolutionary approach, loosening the rules of harmony and rhythm and less dependent on chordal sequences, would be met with fierce blowback from much of the jazz establishment a few months later when he made his New York City debut—and while Manne and bassist Percy Heath were not part of his working group, they still managed to provide a dynamic underpinning to Coleman’s music. And some of the experimental pieces Manne had recorded in previous years seemed to anticipate the direction that Coleman was taking. From 1959, here’s Ornette Coleman and “Tomorrow Is The Question,” on Night Lights:

Ornette Coleman, “Tomorrow Is The Question” (3:09)

Saxophonist Ornette Coleman performing his composition and the title track from his 1959 album TOMORROW IS THE QUESTION, with Don Cherry on trumpet, Percy Heath on bass, and Shelly Manne on drums.

Shelly Manne stayed busy for the remaining 25 years of his life, running his own Los Angeles jazz club from 1960 to 1972, and continuing to lead small groups as well as recording frequently for various film and television projects. He also stayed married to his wife Flip—their marriage had lasted 41 years when Manne died of a heart attack at the age of 64 in 1984.

Shelly Manne once said, “I feel if a drummer could swing, he can play with anybody.” Manne’s 1950s discography brings that principle to musical life. I’ll close with music from one of the live recordings Manne made at San Francisco’s Black Hawk Club in the autumn of 1959 that find him in a hardbop setting—a set of performances so kinetic that the Contemporary label eventually issued five albums drawn from them. Here’s Shelly Manne doing “Whisper Not” on Night Lights:

Shelly Manne, “Whisper Not” (9:44)

I closed with Shelly Manne doing “Whisper Not” from SHELLY MANNE AND HIS MEN AT THE BLACK HAWK Volume 3, with Joe Gordon on trumpet, Richie Kamuca on tenor sax, Monty Budwig on bass, and Victor Feldman on piano. Thanks for tuning into this edition of Night Lights. You can listen to many previous Night Lights programs on our website at wfiu.org/nightlights. Production support for Night Lights comes from Columbus Visitor's Center, celebrating EVERYWHERE ART AND UNEXPECTED ARCHITECTURE in Columbus, Indiana. Modern architecture and design to explore forty-five minutes south of Indianapolis. More at Columbus dot I-N dot U-S. Night Lights is a production of WFIU and part of the educational mission of Indiana University. I’m David Brent Johnson, wishing you good listening for the week ahead.